Fog

FOG, defined by Shaw as a "cloud, devoid of structure, formed on land in the layers of air which, though nearly stationary, really move slowly over the ground." (See CI.oUD.) The same kind of surface cloud may be found at sea accompanied by light breezes or even by wind of fairly considerable force. In its more intense forms it occasions considerable delays and is sometimes so thick as to paralyse traffic completely. Viewed from a distance, fog has a definite boundary which is absent in some other forms of obscurity.

Fog, mist and haze are somewhat indiscriminately used in ordi nary literature. Mist consists of a surface cloud of minute drops of water suspended in the air, e.g., Scotch mist or Dartmoor mizzle; haze should be reserved for smoke or dust obscuration of the lower atmosphere when the air is dry. (See HARMATTAN.) This distinction is often disregarded in practice, and formerly even the Beaufort weather notation had no separate letter for haze (now indicated by z), though fog (f) and mist (m) had separate letters.

The popular distinction between fog and mist is based rather on obscurity effects than on their meteorological character. The phrase "in a fog" has become proverbial, while the usual com pounds for traffic aids are "fog-bell," "fog-horn," when vessels are "fog bound" ; cf. "f og-signal" (railway) ; the word "mist" is seldom used in similar connection. Sailors normally restrict the term to an obscurity of the atmosphere in comparatively calm weather; if the obscurity is produced by strong winds and driving rain the terms employed are "thick" weather or "very thick weather." In the latter case, if passing ships are not sufficiently visible for safe navigation some form of fog-warning becomes a duty.

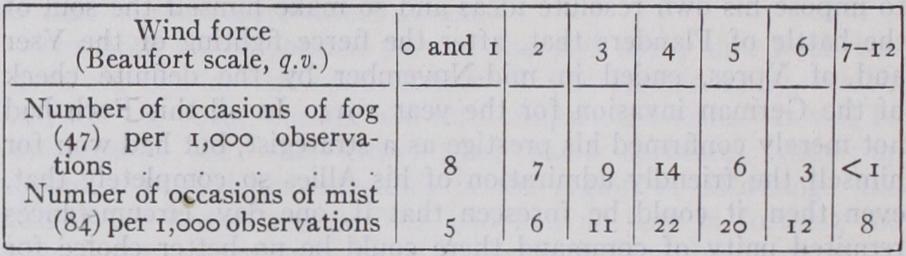

The Seaman's Handbook of Meteorology (Met. Office, No. 1914) contains a series of plates based on over 5o,000 observations taking during the 3o years ending 1908, which show the average distribution of a fog and mist in the vicinity of the British Isles. Another set of observations taken at St. Mary's, Scilly Isles (3o years period), gives the relation between wind force and the occurrence of fog and mist.

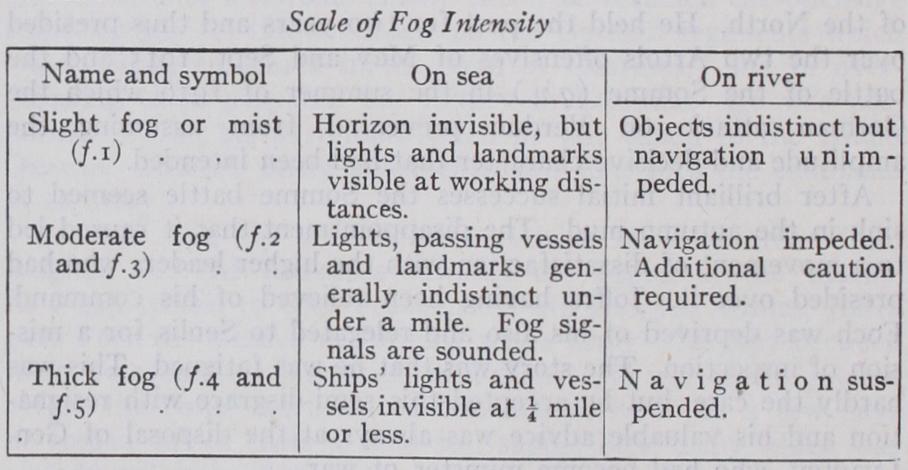

The Meteorological Office. the Admiralty and the Trinity House have adopted a scale of "fog" intensity for the use of observers in estimating and recording grades of obscurity caused by fog or mist.

On land during

f. I although objects are indistinct, road and rail traffic is unaffected; f.2 demands additional caution for rail traf fic; f.3 and f .4 cause road and rail traffic to be impeded; and i.5 results in total disorganization of traffic. Related to this scale is a scale of visibility in which o stands for dense fog, objects not visible at So metres; I, thick fog, objects invisible at 200 metres; 2, fog, objects invisible at 50o metres; and so on up to 9, excellent visibility, objects visible beyond 50,00o metres. At sea or in the country a fog, as a rule, is white and consists of minute water globules forming a cloud of no great vertical thickness which, though it disperses the sunlight, is fully translucent. In large towns the cloud is intensified by smoke, and some dark fogs may be regarded as entirely the result of smoke. The term "high fog" used to describe the blanket of opaque cloud which results in almost complete darkness during daytime in certain large towns, though the streets are clear of obscurity, is a convenient though inaccurate use of the word "fog." The physical processes which produce fogs are complicated. The usual process of cloud formation, namely, the cooling of air consequent on the reduction of pressure during ascent, cannot be applied to these surface-clouds. The only other process hitherto recognized as producing clouds in the atmosphere is the mixing of masses of moist air of different temperatures. The mixing results from a slow motion of the air masses, and this motion is essential to the phenomenon.Over the sea, fog is usually caused by the cooling of a surface layer of air by contact with the underlying colder water. See Shaw, Life History of Surface Air Currents (M.O. Publication 174, 1906, p. 72).

The cooling of the air surface in contact with the sea would, on account of convection, affect only a thin layer, but in addition a churning motion is set up by which the cooling is gradually extended upwards. (See G. I. Taylor, Scientific Results of the Voyage of the Scotia, 1913.) Sea fogs are most prevalent in spring and summer when the air is warming rapidly. Many thousands of observations taken over a period of 15 years (1891-1905) in the English channel give June as the most "foggy" month, followed by April, with Novem ber the least "foggy." The observations for mists give June as the highest, followed by May, and with November again as the least misty. Sea fogs of the type described above demand that the movement of the air mass shall be slow and that the mixing shall neither be too violent nor too widespread in order that the whole mass producing the fog shall be cooled below the dew point (q.v.). From the conditions of its formation sea fog is likely to be less dense at the mast-head than it is on deck.

Shaw suggests that a sea fog is sometimes formed by the slow passage of cold air over relatively warm water, giving a "steam ing-pot" type of fog. In this, the layer in contact with the warm water would be clear and the fog would form aloft where the mixing is more complete. Such "steaming-pot" fogs are, however, rare, for if the existence of a cold current over warm water were a sufficient cause of fog in the same manner that the opposite con ditions appear to be, then the distribution of fog in place and time would be much more extensive than it is at present.

The formation of land fog seems to involve even more compli cated processes. A certain amount of mistiness may arise from the replacement of cold surface air by a warm current, but this would hardly produce large detached banks of fog. The ordinary autumn evening valley fog results from a combination of : the cooling of the surface layer of air during a calm cloudless eve ning by earth radiation; the slow natural gravitational trickle of the cooled air towards lower levels; a certain amount of eddy motion to promote mixing; and the supply of water vapour from warm, moist soil or from a relatively warm water surface. In this way wreaths and banks collect in the lowest parts, until extensive and deep valleys become filled with fog. (For a minute description of a Lake District fog see J. B. Cohen [Q. J. Roy. Met. Soc., vol. xxx., p. 211, 1904].) Hence the circumstances favouring fog formation are (1) a site near the bottom level of a drainage area, (2) cold surface air but no wind, (3) a period of vigorous radiation, (4) warm but moist surface soil.

The persistence of these fog banks is remarkable considering that even the smallest particles of a fog cloud must be continually sinking, and consequently should reach the earth or water and lead to the disappearance of the fog-cloud. In sheltered valleys the constant downward drainage of fresh and colder fog-laden material may displace the lower layers which were clearing, but there are occasions when the extent and persistence of land fog seems too great to be accounted for by such means, e.g., Dec. 1904 when the whole of England south of the Humber was covered with fog for several days.

The very presence of fog, of course, tends to its own preserva tion for much of the solar heat which would otherwise reach the ground and set up convection from below is reflected from the upper surface of the fog screen. Again, during thick fog there is a reversal of the normal temperature distribution of the lower layers and the surface air may be much cooler than the air imme diately above. This reversal of the normal lapse-rate for temper ature confers a special stability on the lower layers ; convection is impossible and the lower layers are practically shut off from the other layers of the atmosphere ; in addition, in large towns the stagnant air becomes further polluted by dust and smoke and this intensifies the fog.

A typical case of inversion of temperatures was noted during the persistent fog of March 6, 1902, when the minimum tempera ture recorded on the Victoria Tower (40o ft. high) of the Houses of Parliament was 74° F higher than the minimum measured in a thermometer screen 4 ft. above the ground. The lowest layers, in such circumstances, may attain very low temperatures. A remarkable example occurred in London on Jan. 28, 1909. The city was under fog all day and the maximum temperature only reached 31° F, whereas Warlingham (Surrey), outside the fog zone, had a temperature of 46° F. It is thus evident that while fog arrests surface cooling by radiation, yet it does not provide a protection for plants against frost. (See DEW.) The somewhat capricious drifting of fog banks over the sea still awaits satisfactory explanation. Shaw suggests that it may be connected with the electrification of particles, as observations at Kew show high electrical potential during fog, but whether this potential is a cause or a result of the fog has not yet been proved. Shaw has also experimentally demonstrated that if a mass of f og bearing air could be enclosed and kept still for but a short time then the fog would settle; hence as one essential condition of fog formation is the process of mixing, then the apparently capricious behaviour of fog banks may mean that mixing is still going on in the persistent ones, but is completed in the disappearing ones.

Statistics on the geographical distribution of fog are usually not very satisfactory on account of the uncertainty of the distinc tion between fog and mist. Nevertheless, certain areas have been well mapped, e.g., the north Atlantic ocean and its various coasts as shown in the monthly meteorological charts of the north At lantic issued by the Meteorological Office, and in the pilot charts of the north Atlantic of the United States Hydrographic Office. These charts show that ocean fog is most extensive in the spring and summer. By June the fog area has extended from the Great Banks over the ocean to the British Isles, in July it is most intense and by August it has notably diminished, while in November, proverbially a foggy month on land, hardly any ocean fog remains.

The various meteorological aspects of fog and its incidence in certain areas are set out in numerous papers. As far back as 1889 the titles referring to fog, mist and haze in the Bibliography of Meteorology (Pt. 2. U.S. Signal Office) numbered 3o6, and there have been very numerous additions. The fogs of London in par ticular have long been the subject of inquiry, and reports were prepared by A. Carpenter and R. G. K. Lempfert, based upon observations made between 1901 and 1903, in order to examine the possibility of more precise forecasts of fog. (See Met. Office Publication, No. 16o.) The study of the properties of fog is especially important for large towns in consequence of the resultant economic and hygienic effects, but it is difficult to get trustworthy statistics in conse quence of the vagueness in the classification of fog. For large towns there is great advantage in using a fog intensity scale such as that given above.

Assuming that the term fog means an obscurity amounting to f2 or more on the scale, it then becomes possible to determine comparative frequencies between places or for the same place at different periods. From such a comparison Brodie suggests (Q.J.R. Met. Soc., vol. xxxi. p. 15) that in recent years there has been a marked diminution of fog frequency as indicated by the following total number of days of fog for the separate years 1871 to 1908.

1871-188o: 35, 75, 53, 49, 74.

1881-1890: 59, 61, 53, 86, 62, 75, 65.

1891-1900: 69, 68, 31, 51, 48, 43, 47, 56, 13.

45, 42, 26, 44, 19, 16, 37, But neither the above statistics, nor later figures, nor common experience suggests that the atmosphere of London is approaching that of the rural districts as regards transparency. Autographic records still show that the atmosphere in many parts of the metropolis is almost opaque to sunshine strong enough to burn the card of the recorder during the winter months, and any sub stantial reduction of the obscuring pall will only follow a serious handling of the smoke abatement problem. (Sec Sir Napier Shaw and J. S. Owens, The Smoke Problem of Great Cities, 1925.) In this connection it is interesting to note that there was a marked diminution of the smoke layer over Britain during the fuel short age which accompanied the labour disputes of 1926.