Fontenoy

FONTENOY, a village of Belgium, in the province of Hen negau, about 4m. S.E. of Tournai, famous as the scene of the battle of Fontenoy, in which on May i 1, 1745, the French army under Marshal Saxe defeated the Anglo-Allied army under the duke of Cumberland. The object of the French (see also AUs TRIAN SUCCESSION, WAR OF THE) was to cover the siege of the then important fortress of Tournai ; that of the Allies, who slowly advanced from the east, to relieve it. Informed of the impending attack, Louis XV., with the dauphin, came with all speed to wit ness the operations, and by his presence to give Saxe, who was in bad health and beset with private enemies, the support necessary to enable him to command effectively. Under Cumberland served the Austrian field-marshal Konigsegg, and, at the head of the Dutch contingent, the prince of Waldeck.

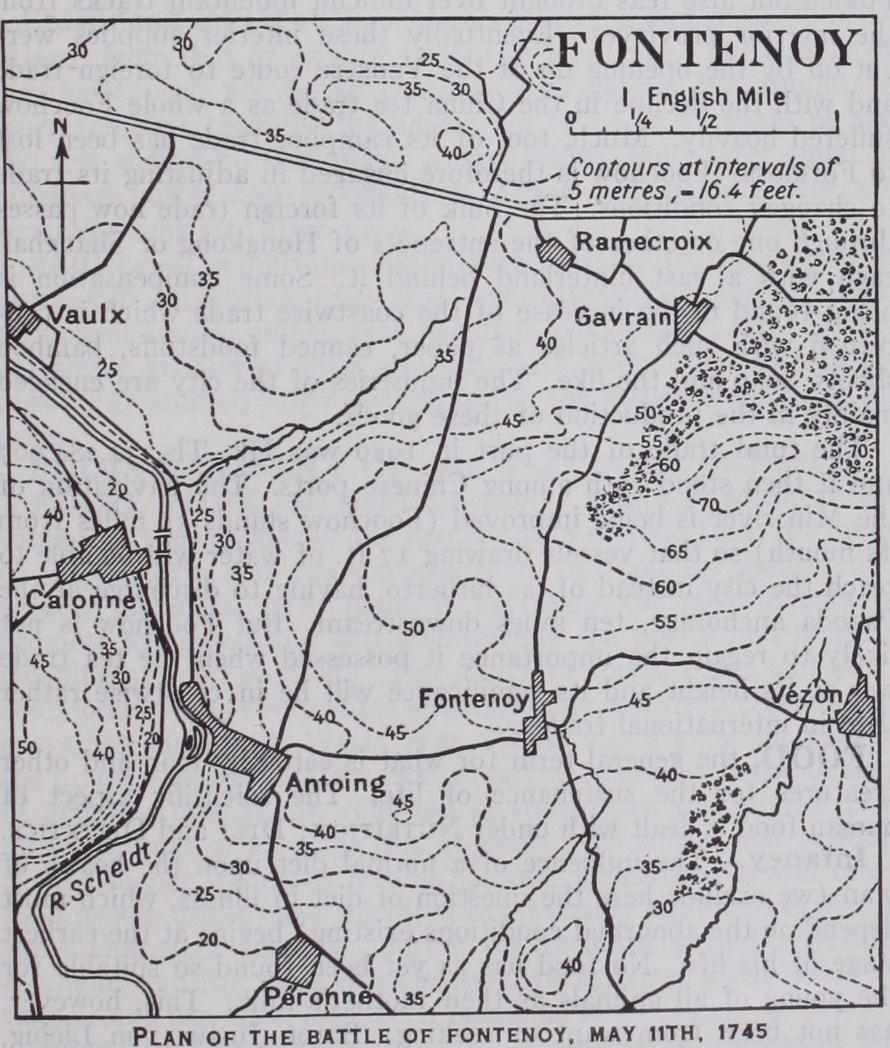

The right of the French position (see map) rested on the river at Antoing, which village was fortified and garrisoned ; between Antoing and Fontenoy three square redoubts were constructed; and Fontenoy itself was put in a complete state of defence. On the left rear of this line, and separated from Fontenoy by some furlongs of open ground, another redoubt was made at the corner of the wood of Barry and a fifth towards Gavrain. The infantry was arrayed in deployed lines behind the Antoing-Fontenoy re doubts and the low ridge between Fontenoy and the wood ; behind them was the cavalry. Marshal Saxe himself, who was suffering from dropsy to such an extent that he was unable to mount his horse, slept in a wicker chariot in the midst of the troops. At early dawn of May I I, the Anglo-Hanoverian army with the Austrian contingent formed up in front of Vezon, facing towards Fontenoy and the wood, while the Dutch on their left extended the general line to Peronne. The total force was 46,00o against 52,00o whom Saxe could actually put into the line of battle.

It was resolved that the Dutch should attack the front Antoing Fontenoy, while Cumberland should deliver a flank attack against Fontenoy and all in rear of it, by way of the open ground between Fontenoy and the wood. A great cavalry attack round the wood was projected but had to be given up, as in the late evening of the loth the Allies' light cavalry drew fire from its southern edge. Cumberland then ordered his cavalry commander to forma screen facing Fontenoy, so as to cover the formation of the infantry. On the morning of the I I th another and most important modifica tion had to be made. The advance was beginning when the re doubt at the corner of the wood became visible. Cumberland hastily told off Brigadier James Ingoldsby to storm this redoubt which, crossing its fire with that of Fontenoy, seemed absolutely to inhibit the development of the flank attack. At 6 A.M. the brigade moved off, but it was irresolutely handled ; and after wait ing as long as possible, the British and Hanoverian cavalry rode forward and extended in the plain, becoming the target for a furious cannonade which drove them back. Thereupon Sir John (Lord) Ligonier, whose deployment the squadrons were to have covered, let them pass to the rear, and pushed the British infantry forward through the lanes, each unit on reaching open ground covering the exit and deployment of the one in the rear, all under the French cannonade. This went on for two hours, and save that it showed the magnificent discipline of the British and Hano verian regiments, was a bad prelude to the real attack.

It was now 9 A.M., and while the guns from the wood redoubt battered the upright ranks of the Allies, Ingoldsby's brigade was huddled together, motionless, on the right. Cumberland himself galloped thither, and under his reproaches Ingoldsby lost the last remnants of self-possession. To Ligonier's aide-de-camp, who de livered soon afterwards a bitterly formal order to advance, In goldsby sullenly replied that the duke's orders were for him to advance in line with Ligonier's main body. By now, too, the Dutch advance against Antoing-Fontenoy had collapsed.

But on the right the cannonade and the blunders together had roused a stern and almost blind anger in the leaders and the men they led. Ingoldsby was wounded, and his successor, the Hano verian general Zastrow, gave up the right attack and brought his battalions into the main body. Meantime the young duke and the old Austrian field-marshal had agreed to take all risks and to storm through between Fontenoy and the wood redoubt, and had launched the great attack, one of the most celebrated in the history of war. The English infantry was in two lines. The Hanoverians on their left, owing to want of space, were compelled to file into third line behind the redcoats, and on their outer flanks were the battalions that had been with Ingoldsby. A few guns, man-drawn, accompanied the assaulting mass, and the cavalry followed. The column may have numbered 14,00o infantry. All the infantry battalions closed on their centre, the normal three ranks becoming six. (If the proper distances between lines were preserved, the mass must have formed an oblong about 5ooyd. X 600yd.) .

The duke of Cumberland placed himself at the head of the front line and gave the signal to advance. Slowly and in parade order, drums beating and colours flying, the mass advanced, straight up the gentle slope, which was swept everywhere by the flanking artillery of the defence. When the first line reached the low crest, the fire became a full enfilade from both sides, and at the same moment the enemy's horse and foot became visible be yond. A brief pause ensued, and the front gradually contracted as regiments shouldered inwards to avoid the fire. Then the French advanced, and the Guards Brigade and the Gardes Francaises met face to face. Captain Lord Charles Hay, lieutenant of the First (Grenadier) Guards, suddenly ran in front of the line, took off his hat to the enemy and drank to them from a pocket flask, shouting a taunt, "We hope you will stand till we come up to you and not swim the river as you did at Dettingen," then, turning to his own men, he called for three cheers. The astonished French officers returned the salute and gave a ragged Whether or not the French, as legend states, were asked and re fused to fire first, the whole British line fired one tremendous series of volleys by companies. Fifty officers and 76o men of the three foremost French regiments fell at once, and at so appalling a loss the remnant broke and fled. Three hundred paces farther on stood the second line of the French, and slowly the mass advanced, firing regular volleys. It was now well inside the French position, and no longer felt the enfilade fire that swept the crest it had passed over. Spasmodic counter-attacks on its flanks were re pelled but these gained a few precious minutes for the French. It was the crisis of the battle. The king, though the court medi tated flight, stood steady with the dauphin at his side—Fontenoy was the one great day of Louis XV.'s life—and Saxe, ill as he was, mounted his horse to collect his cavalry for a charge. The British and Hanoverians were now at a standstill. More and heavier counter-strokes were repulsed, but no progress was made; their cavalry was unable to get to the front, and Saxe was by now thinking of victory. Captain Isnard of the Touraine regiment sug gested artillery to batter the face of the square, preparatory to a final charge. The nearest guns were planted in front of the assail ants, and used with effect. The infantry led by Lowendahl, fas tened itself on the sides of the square. On the front, waiting for the cannon to do its work, were the Maison du Roi, the Gendar merie and all the light cavalry. The left wing of the Allies was still inactive, and French troops were brought up from Antoing and Fontenoy to support the final blow, about 2 P.M. In eight minutes the square was broken. As the infantry retired across the plain in small stubborn groups all attempts to close with them were repulsed by the terrible volleys, and they regained the broken ground about Vezon, whence they had come. Cumberland himself and all the senior generals remained with the rearguard.

The losses at Fontenoy were exceedingly severe in the units really engaged. Eight out of nineteen regiments of British infantry lost over 200 men, two of these more than 300. The Hanoverian regiments suffered as heavily in proportion. The total loss was about 7,500, that of the French 7,200.

Fontenoy was in the 18th century what the attack of the Prus sian Guards at St. Privat was in the next, a locus classicus for mili tary theorists. But the technical features of the battle are com pletely overshadowed by its epic interest.