Forests and Forestry

FORESTS AND FORESTRY. The meaning of the word "forest" has undergone many changes with the change in economic, political and social conditions of the people. Originally the word "voorst" or forest designated the segregated property of the king or leader of the tribe. Toward the end of the eighth century, it referred to all the royal woods in which the right to hunt was reserved by the king, but other rights, such as the right to cut wood, clear for agricultural use or pasture, remained free to all. Toward the end of the ninth century, "forest" meant a large tract of land, including woods as well as pastures and whole villages, on which not only the rights to the chase were reserved to the king but also all other rights, often even the activities of the persons themselves living on it, were restricted. "Forest" was a legal term, applied to a large tract of land or district governed by special "forest laws," with the royal prerogative—"the right to hunt"—as the basis. The forests of Dean, Windsor, Epping and Sherwood, and the New Forest in England, made famous by legend and history, were such legal districts set aside by the Norman kings for their pastime. With the decadence of the regal prerogative, the old legal meaning wore away, and "forest" came to mean a natural condition, land covered by wood growth as contrasted to prairies and plains, meadows and field.

In modern times as the economic aspect of forests as a source of wood material came more into the foreground, "forest" came to mean a woodland, whether of natural growth or planted by man, designated as an object of man's care for the growing of timber and other forest products. With the advance of plant science, better understanding of the nature of the forest, its life history, and its relation to climate, soil and other environmental factors, the forest is conceived as a biological entity—a plant society governed by definite natural laws, the knowledge of which is basic to intelligent management of the forest as an economic resource. The present conception, then, of a forest is that of a plant society of arborescent and shrub species, which has both an economic and biological significance. Its economic significance lies in the production of timber and other forest products. Its biological significance lies in its effect upon climate, streamflow, protection of the soil from erosion, and in the mutual relationships that exist between the trees in the forest.

Role of Forests in Human History.

The relations between forests and man are manifold and varied throughout the course of human progress from the primitive stage to the present highly developed economic organization. Forests have had an important effect on the distribution of mankind over the earth's surface. They have deeply affected the spiritual and religious life of the tribes living within them or nearby. They have been a source of raw material, indispensable to the economic development of the human race.At the dawn of human history, the forests did not offer favour able conditions for the settlement of primitive man; on the con trary, they were always an element inimical to the spread of mankind over the earth.

Only a few traces of prehistoric man are found in densely forested regions. The chief memorials of Neolithic man in Britain are found on the moorlands, which at that time appeared as islands of open, habitable land, above the vast stretches of swamp and forest. The first cradle of human civilization was not a primeval forest. The first great nuclei of population, the seats of the earliest recorded civilizations both in the Old and in the New World, originated in arid regions, at best only scantily covered with forests. In the Old World, the Egyptian, Babylonian, As syrian and Phoenician civilizations arose in hot and dry regions. Similarly, in the New World, the nations which developed a high degree of civilization were those in the arid regions of Mexico and Peru—the Aztecs and the Incas.

Barriers to Travel.

Forests have acted as barriers to human colonization in all parts of the world. It took the American col onists about 200 years to reach the crest of the Appalachians. The expansion of the Inca empire from the high plateaus of Peru and Bolivia eastward was limited by the impenetrable forests of the headwaters of the Amazon river. The Romans, the greatest colonizers of ancient times, were forced to stop in their expansion and empire building at the boundaries of the dense, virgin German forests. Later, the successive waves of nomadic tribes which moved from the eastern prairies westward—Huns, Magyars, Avars, and the like—broke up when they reached the barrier of primeval forests. The routes of migration in western and central Europe were largely determined by the openings in the primeval forest.The difficulty of travel in the forests made them play during early stages of human culture, the part of territorial boundaries. Forests formed political boundaries in the ancient nations of cen tral Europe. According to Grimm, the German word, mark, which means boundary, was originally a synonym of Waldland, or wood land. Even today, among the more primitive races, forests still serve as political boundaries. When the forests did not afford a safe defence in themselves, then the natives resorted to the con struction of additional barriers, which, primitive as they may seem to us at present, probably proved very effective for those times.

As a source of fuel, the forest has exerted a most powerful influence upon human progress. The polar boundary of human settlement in the interior of northern Asia and North America closely coincides with the northern limit of forest vegetation. In Alaska, the northern timber limit reaches as far as 67° N.; in Labrador, it ends at 52° N., or 15 degrees farther southward. The Indian settlements follow closely these fluctuations of the northern timber line.

Cultural Influence.—The forest left a deep impression upon the soul of primitive man. The forest figures largely in the reli gious beliefs of primitive races all over the world. With many primitive peoples, trees are considered to be the abode of the souls of the dead. The Hindu philosopher, Tagore, in his book on The Realization of Life, describes very vividly the part which the Indian forests have played in the development of Indian civiliza tion and philosophy. The influence of the forest upon the spiritual life of man is not confined, however, to primitive tribes. The folklore of North American Indian, Teuton and Slav is per meated with the atmosphere and joy of the forest.

Landscape painting has drawn much inspiration from the forest. The forest is a great natural structure from which architecture has often borrowed its form. The trunks of the trees gave rise to the pillars of stone. The bending branches served as models for arches, and foliage and flowers provided the ornaments adorning many works of man. Music has also found inspiration in the dense forest.

Domination of Primitive Man.—At the low stages of de velopment, man is dominated by the forest. Primitive man, pos sessing crude stone implements only, found but few parts of the earth's surface which were neither too barren nor too heavily forested to be suitable for his habitation. When, however, the arts of life advanced, man learned to overcome forest and other natural difficulties. At a certain stage there begins, therefore, a reverse influence, namely, that of man upon forest, the penetra tion of forests by man.

The primitive nations could not change to any marked degree the forest cover of the earth. Their tools were too crude and, moreover, their activities were rarely concentrated at the same place for any length of time, because their mode of life was largely nomadic.. The dense forests of central Europe did not give way before the efforts of the Romans or the ancient Teutons. Only in the middle ages, beginning with the era of Charlemagne, when there arose an imperative need for more room, did the Teu tons succeed in clearing any large areas of the dense forest. This was not the work of individuals, but was the result of many concentrated and persistent efforts on the part of the re ligious and knightly orders.

Forest Settlements.—The earliest settlements in the forest were comparatively small. In the earlier settlements, the sur rounding forest served as a supplementary source of food for the primitive agriculturist. The cultivation of small parcels of cleared land was supplemented by grazing of stock in the oak or other adjoining forest. The forest also furnished acorns as food for animals and even man, while the wild animals provided meat and hides.

As the gathering of wild plants is displaced gradually in the course of economic evolution by the regular production of culti vated crops, grazing supersedes the hunting of game. As an inter mediate stage from hunting to stock raising, there is often do mestication of animals, as, for instance, the breeding of foxes in a state of semi-domestication, or the raising of bees. In the primi tive horticulture of the primeval forests, it was customary to cut down the trees in the portion of the forest destined for cultivation, then to burn all the wood or at least the branches and underbrush. The ashes served as fertilizer ; the ground was broken, and the seed, shoots, or tubers were planted. The peasants of eastern Russia, as well as some agricultural colonists in South America, burn the forest and cultivate the ground for some years, merely to abandon it and repeat the same process every io or 15 years.

Use of Forest Products.—Extensive as this form of agri culture may be, it in itself would not have been sufficient to have reduced the forested area of the world to its present size. It is the increased needs for the products of the forest itself, par ticularly its timber, that has made the heaviest inroads upon it. Next to food, wood has been one of the most important factors of civilization, particularly at the time when iron, brick and other structural materials were either unknown or little used. In the early stages of economic development, the forests furnished man with fuel for overcoming the rigours of winter cold. It furnished fuel also for metal working, and a number of secondary products, such as charcoal, pitch, ashes, gallnuts, some of which were more widely used in the past than they are now. At a higher stage of civilization and with the development of means of communication and transportation, the products of the forest are no longer merely the means with which to satisfy immediate needs; they become commodities of widespread use far beyond the forest boundary. Many industries, which were dependent upon wood as fuel, found their location in the forest. Thus, the occurrence in the same area of forests and mineral deposits gave rise to metallurgy and the art of glass making. In France about the t 5th century, before the invention of high ovens, metallurgists and glass makers resided in the forest. In the Middle Ages, an entire forest population, employed exclusively in industries grow ing out of the use of wood, lived in the forests of France. Kilns, charcoal furnaces, forges, glass furnaces, limekilns, and establish ments where wood was worked up gave a peculiar aspect to the forests of that time. In the Ural mountains of Russia, the metal lurgical industry is still closely connected with the forest, from which the necessary charcoal is obtained. The forests of the eastern United States were once extensively used for charcoal making, in connection with the iron industry.

Role of Navigable Rivers.—The penetration of the forests and the development of forest industries have been greatly favoured by rivers. Water courses, penetrating forest regions, are the natural means of access and with their banks constitute the first zone of attack on the phalanx of the forest. This was the case in Europe ; the Rhine and its tributaries formed the principal routes by which extensive openings could be made in the German forests. The same was true in Italy during the Roman epoch, when the Aniene, the Liri and the Chiana served as means of trans porting wood from the Apennines, and wood from the Alps reached Rome by way of rivers and the ocean. The vast territory included between Hudson bay and the Saskatchewan river was revealed to missionaries and fur dealers—voyageurs, coiffeurs de bois—by way of the St. Lawrence river. The development of the lumber industry in the United States and Canada in the early days would not have been so rapid had it not been for the prox imity of the New England forests to the coast and the large num ber of navigable streams. Where forests lack navigable rivers, they remain intact for a long time.

Influence on Pioneer Character.

The battle against the forest has left a deep influence upon the life and character of man. Many of the specific pioneer traits of the original settlers in the United States may be traced to their battle against the forest on the slopes of the Alleghenies to provide a place for settlement. The hazardous work of hewing farms out of the virgin forest bred a race of men of sturdy character and of enormous enterprise and self-reliance. In the United States, this pioneer life of the settler in combating the forest has produced leaders, such as Lincoln, Henry Clay, Jackson, Benton, Cass and scores of others, who for over half a century helped to shape the destiny of their country. The entire ancient history of Sweden may also be reduced to the same struggle with the primeval forest. It is the colonization of the forests of northern Russia that has developed in the Russian people the necessary qualities which enabled them to spread to Siberia and take possession of it. If, of all the present nations, the Anglo-Saxons, Teutons and the Russians display the great colonizing capacity, may it not be attributed largely to their original impenetrable forests, in the struggle with which they have developed the persistence and un relenting energy required for pioneer work? Forest Restoration Imperative.—As man progressed, his capacity for mastering the forest and other natural obstacles in creased manifold with the result that over a large part of the world the forest is now conquered. It is not only conquered, it is exterminated beyond any possible chance of natural recovery. It has now become important to civilization to preserve and restore the forest instead of struggling against it.The disappearance of the forest has not done away with the use of wood by the present civilization ; on the contrary, it has only intensified it. The clearing of the forest, aside from depriving the thickly settled and highly civilized countries of timber needed for their industries, has produced other bad economic and social effects. The stripping of the mountain forests resulted in the occurrence of torrents, in erosion, in floods and in a general change in the regime of streams. The disappearance of the forest has also affected the climate and with the growth of industrialism has resulted in the physical deterioration of a large part of the popula tion. Much of the forest land that has been cleared on mountain slopes, sandy plains or rocky hills, has proved unsuitable for agri culture and has failed to provide room for permanent settlement.

The products of the forest have now become altogether too valuable and no civilized nation can afford forest devastation on a large scale without regard to the future possibilities of the land. Practically all of the civilized countries of the world have now come to realize that there is a point where further clearing of the forest, no matter how dense the population may be, proves detri mental to progress itself. Europe reached that point several centuries ago.

The lesson of the older countries found a reaction also in countries still having abundant forests. In practically the entire civilized world, a new economic force has now been born—a general appreciation of the value of the forest and a movement toward the introduction of rational forest management.

Forests and Climate.

Observations continued for many years in different parts of the world establish with certainty the fol lowing facts with regard to the influence of forests upon climate: The forest lowers the temperature of the air inside and above it. The vertical influence of forests upon temperature extends in some cases to a height of 5,000 feet. The yearly mean tempera ture at equal elevations and in the same locality has invariably been found to be less inside than outside a forest. In a level country this difference is about o•9° F. It increases, however, with altitude, and at an elevation of about 3,00o f t. is 1.8 ° F. The monthly mean temperature is less in the forest than in the open for each month of the year, but the difference is greatest during the summer months, when it may reach 3.6° F, while in winter it does not often exceed o• r ° F. The daily mean temperature shows the same difference, but to a greater degree. During the hottest days the air inside the forest was more than 5° F cooler than that outside, while for the coldest days of the year the difference was only 1.8 ° F. The temperature of the air within the forest is, there fore, not only lower but also subject to less fluctuation than in the open.In tropical and subtropical regions, the influence of the forest upon the temperature of the air is the greatest. Forests influence the temperature of the soil in almost the same way as they do that of the air, except that the differences are greater in the case of soil. The forest soil is warmer in winter by 1.8° F and cooler in summer by 5.4° to 9° F than soil without a forest cover, and this holds true for a depth of as much as 4 feet. In the spring, and especially in the summer, the forest soil is cooler than that of open land. In the autumn and winter, however, it is warmer, but the degree of difference is always less than in summer. The soil under the forest may remain soft when the ground in the open is frozen hard to some depth. If it does freeze, it is to a depth of one-half to less than three-fourths of that in the open.

Forests and Rainfall.

In the summer the relative humidity of the air is higher in the forest than in the open. This difference is usually between 4 and io%, but in some places may be as much as 12%. In regions of heavy snow there is practically no difference in the relative humidity during the spring, when the snow melts. The evaporation of water in the forest from the soil under forest cover is considerably less than in the open. The wind movement in the open is greater than in the forest.Of the total amount of precipitation that falls over the forest only 83% reaches the ground under the forest in the winter and 70% in the summer. The temperature of the trunks, branches, and twigs is always lower than the temperature of surrounding air. This is true for day and night, winter and summer.

This difference in the temperature causes the formation of dew on the branches. The difference in the temperature of the air in the forest and open field is the cause of air currents from the forest into the field and reverse. These movements facilitate the for mation of dew and fogs over fields adjoining forests. In the spring and autumn, these fogs save the fields from early frosts and in the summer from damage by hail. Repeatedly and in different countries it has been observed that forests prevent hail falling over the fields adjoining the forest. Coniferous forests have the greatest effect in deflecting hail storms. Statistics col lected for 20 years, from 1877 to 1897, by a company insuring against hail, confirm the fact that forestless regions are subject to hail storms very frequently, while in forested regions hail storms are of very rare occurrence.

Although there is no complete agreement as to whether forests actually increase precipitation, most observations tend to show that forests do increase both the abundance and frequency of local precipitation over the areas they occupy. The excess of precip itation, as compared with that of adjoining unforested regions, amounts in some cases to more than 2 5 %.

The influence of mountains upon precipitation is increased by the presence of forests. The influence of forests upon local pre cipitation is more marked in the mountains than in the plains.

Forests in broad continental valleys enrich with moisture the prevailing air currents that pass over them, and thus enable larger quantities of moisture to penetrate into the interior of the con tinent. The destruction of such forests, especially if followed by weak, herbaceous vegetation or complete baring of the ground, affects the climate, not necessarily of the locality where the forests are destroyed, but of the drier regions into which the air currents flow.

While the influence of mountain forests upon local precipitation is greater than that of forests in level countries, their effect upon the humidity of the region lying in the lee of them is not very great.

Forests and Waters.

The hydrological role of forests in level countries differs from that of forests in hilly or mountainous regions.In level country, the forests constitute an effective means of draining and drying up swampy lands, the breeding places of malaria and fever-carrying insects. The reforestation of the Landes, Sologne, the Pontine marshes, and a hundred other ex amples prove this. It draws moisture from a greater depth than does any other plant organism, thus affecting the unutilized water of the lower horizontal strata by bringing it again into the general circulation of water in the atmosphere, and making it available for vegetation. While it lowers to some extent the sub terranean water level, it has no injurious effect upon springs, since these are practically lacking in the level countries with hori zontal geological strata where its lowering influence has been chiefly noted. It refreshes the air above it and increases the con densation of moisture carried by the winds, thus increasing the frequency of rains during the vegetative season.

In hilly and mountainous country, forests are conservers of water for streamflow. Even on the steepest slopes they create conditions with regard to surface run-off such as obtain in a level country. Irrespective of species, they save a greater amount of precipitation for streamflow than does any other vegetable cover similarly situated. They increase underground storage of water to a larger extent than do any other vegetable cover or bare surfaces. The steeper the slope, the less permeable the soil, and the heavier the precipitation, the greater is this effect. In the mountains, the forests, by breaking the violence of rain, retarding the melting of snow, increasing the absorptive capacity of the soil cover, pre venting erosion and checking surface run-off in general, increase underground seepage, and so tend to maintain a steady flow of water in streams.

Forests and Soil Erosion.—One far-reaching influence of the forest upon streamflow lies in its ability to protect the soil from washing. The forest is the most effective agent for protecting soil from erosion because (I) the resistance of the soil to erosive action is increased by the roots of the trees, which hold the soil firmer in place, and (2) at the same time the erosive force of the run-off is itself reduced because the rate of its flow is checked, and its distribution over the surface equalized. Erosion has a bearing on the height of flood waters in the rivers, since the sediment carried by the rivers and the coarser detritus brought down by mountain streams often increase stream volume to such an extent that the height of the water is raised far beyond the point it would reach if it came free of detritus and sediment.

When the channel of a stream has become filled with waste material, even a slight rainfall will cause a flood, while if the channel were deep it would have no perceptible effect upon the height of water in the stream. The filling of mountain streams with waste not only increases the frequency of floods but causes the streams to assume the character of torrents.

Floods, which are produced by exceptional meteorological con ditions, cannot be prevented by forests, but without the mitigating influence of the latter, they are more severe and destructive.

Forests and Public Hygiene.—The hygienic influence of forest air is due to its great purity. Forest air is free of smoke, particles of dust, and injurious gases, which are found in the air of cities. All kinds of bacteria are less numerous in the forest air than in the outskirts, generally from 23 to 28 times less. The foliage of the trees acts as a kind of filter and retains the dust and other particles which are contained in the air that passes over a forest. The bacteria retained on the leaves are then readily killed by exposure to the sun.

The former idea that the forest air contains more oxygen and less carbon dioxide has not been confirmed. The amount of oxy gen exhaled by a forest is insignificant and is offset by the in crease of carbon dioxide, resulting from the decomposition of organic matter in the floor of the forest. Ozone, which is usually absent from the air of cities, has been found in quantities in the forest, just as it is found in the mountains and on the sea shore. Hydrogen peroxide was found also to exist in minute quantities in the air of the forest, but what its hygienic importance may be is not known..

The soil of the forest was found to contain less albuminoid matter and salts suitable for bacterial growth. Moreover, the humus produced by the growth of trees is inimical to pathogenic bacteria, which up to the present time have not been found in the soil of forests.

It was shown that the soil has an important bearing upon the spread of cholera and typhoid fever. In India, it is claimed that villages surrounded by forests are never visited by cholera, and troops are removed to barracks built in the forest to arrest the disease. Huffel confirms this by the statement that the town of Haguenau in Alsace, surrounded by a dense forest nearly 5o,000 ac. in extent, was always free from the epidemics of cholera which in the last century attacked several times the other towns in the same district. Forests by affording protection against prevailing cold and humid winds make life more healthy and bearable in districts subject to such winds.

The advent of the automobile and the opening of remote forests with highways have made them accessible to large masses of people and enhanced tremendously their recreational value. In some localities of Canada and the United States, the recreational value of the forests exceeds their value as a source of raw materials.

Occurrence of Forests.—Forests grow naturally only where there is present a certain minimum of heat and moisture. Accord ing to Heinrich Mayr, forests can grow only where the average temperature during the four months of the vegetative period (in the northern hemisphere—May, June, July and August, and in the southern—November, December, January and February) does not fall below 50° F and where during the same four vege tative months the precipitation is above two inches.

The warm ocean currents (the Gulf stream and Japan current, Juro Siwo) raise the northern limit of the forest from 57° north ern latitude to 65°. The northern coast of America, Greenland, the north of European Russia and Siberia are forestless because of lack of heat. The south-eastern extremity of South America, central Africa, Sahara, Arabia, Persia, Gobi, the west coast of central Africa, and the interior of Australia are treeless because of lack of moisture.

In many parts of the earth's surface, where no natural forest occurs, forests, however, can be established artificially. The young trees require certain favourable conditions of heat and moisture for their development during the early years of their life. Once such conditions are afforded them in artificial ref oresta tion by means of irrigation and cultivation, they themselves create later under the forest canopy conditions for their further development.

Kinds of Forests.—The forests of the world may be classified broadly into three main groups, conifers (softwoods), temperate hardwoods, and tropical hardwoods. For the world as a whole, conifer forests (pines, spruces, firs, hemlocks, larches, cedars, sequoias and cypresses) occupy 35.4% of the forest area; tem perate hardwoods (oaks, maples, birches, poplars, etc.), 16%; and tropical hardwoods (mahogany, fustic, logwood, balsa, rose wood, teak, cedrela, ebony, etc.), 48.6%. Fig. 1.

A most striking fact, and one of great economic significance, is that 95% of the conifer forests upon which the world depends for its construction material and 89% of the temperate hardwood forests are in the north temperate zone. This zone, including Europe, most of Asia, and North America, and the north coast of Africa, has almost three-fourths of the world's population and consumes an even greater share of the timber used in the world. The tropical hardwoods are confined to the tropical and adjacent subtropical regions of the earth, which have less than one-fourth of the population.

Original Forest Area.—In prehistoric times and also accord ing to tradition and the written record of the earliest historic times, forests occupied a much larger proportion of the earth's surface. As a result of land clearing and forest fires, that followed in the wake of forest exploitation, much of the original forest has disappeared.

With the exception possibly of China, the greatest change has taken place in Europe, where of a total land area of nearly 21 billion acres, only one-third, or 774 million acres, remains in forest. Almost two-thirds of this, or about 500 million acres, is in Euro pean Russia and Finland, and only 275 million acres in the rest of Europe. In Great Britain 95% of the original forest is gone; in France, Spain, Belgium, Italy and Greece, from 8o to 90% of the original forest has been destroyed; while Sweden and Fin land are the only countries with half of their forests left. The forest area of Norway has been reduced 2 million acres from 1875 to 1907. In European Russia the privately owned forests shrunk between 188o and 1913 by about 25 million acres. In Serbia the forest area has decreased 121% from 1889 to 1904.

In the United States of North America, the original forest has shrunk more than 40% in the course of three centuries. Can ada's productive forest area is decreasing at the rate of about 3 or 4 million acres a year. Large areas of forest have been cleared in the more populous regions of Africa and South America, and even in the less developed regions the process is going on slowly but steadily. The World War still further accelerated this process. The forests in the occupied territories have been greatly depleted, as, for instance, in Belgium. Great forest devastation occurred also in northern France and Poland. The demands of war caused over-cutting in many other central European countries.

Present Forest Area.

The present forest area in round figures is about 71 billion acres, which is 22% of the land area, exclusive of the polar regions. This is 4.35 acres per capita for the popu lation of the world. The area of actually productive forest, how ever, is probably one-fourth less than this amount, or 51- billion J acres, which is i6% of the land area, and 3.2 acres per capita. The present distribution of the forests among the six grand divisions of the earth's surface is shown in fig. 2.The extent of forests in individual countries, together with the ratio of forests to total land area of each country and the relation of forest area to population, are given in Table I.

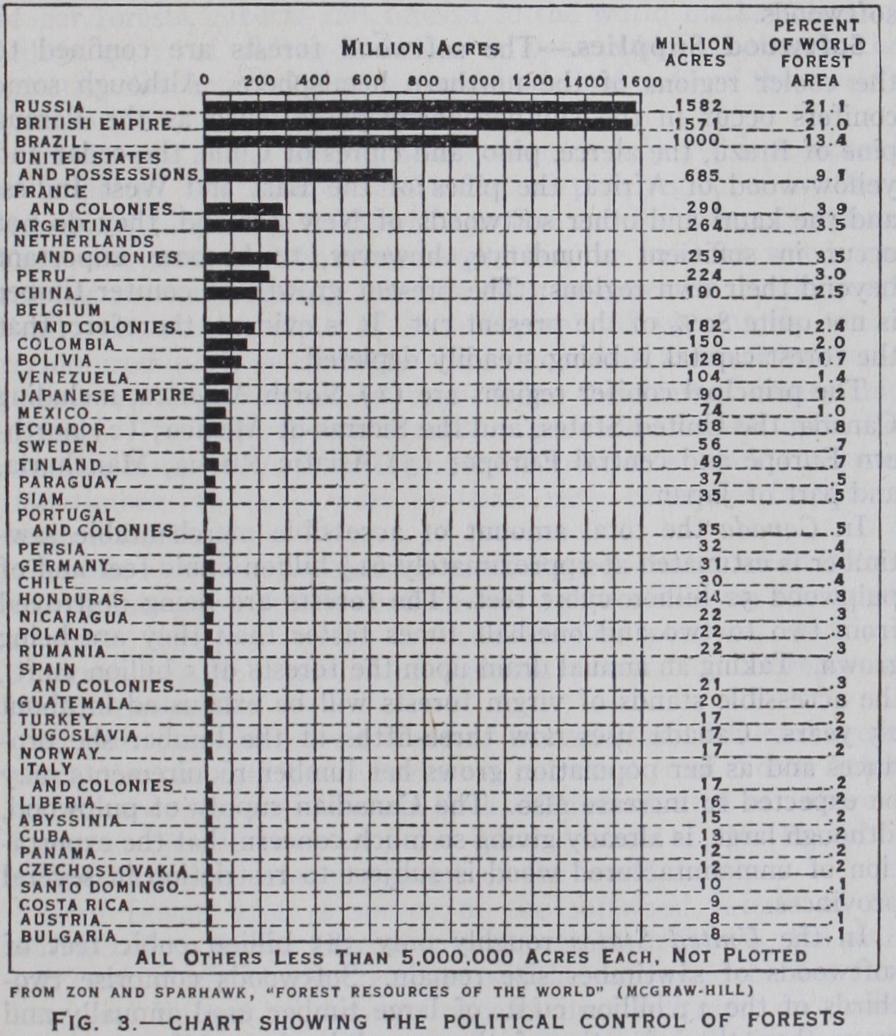

Political Control of Forest Wealth.

If the forests of the colonies, protectorates and dependencies are added to those of their mother countries, we obtain a picture of the political control of the forests of the world (fig. 3).Russia has the most extensive forests and the British empire is a very close second. Each has more than one-fifth of the world's forests. Brazil and the United States come next, and these four countries together have nearly two-thirds of the forest land of the world. The remaining one-third is divided among about so coun tries. It is interesting to note that Great Britain, France, Belgium and the Netherlands, which together have but 0.4% of the world's forests, control more than 3o% in their colonies and dependencies.

World Production and Consumption of Wood.

In spite of the fact that this is the "age of coal, iron, steam and electricity," wood still forms the basis of modern civilization. The world pro duction and consumption of wood amounts to approximately 56 billion cu.ft., which is an average of 32 cu.ft. per capita, or a cut of 7.5 cu.ft. per acre of forest. Almost half of it, or nearly 26 billion feet, is sawtimber, and 3o billion feet is fire wood.As populations grow and as living standards rise and human wants become more complex, timber consumption increases, in spite of the extensive and growing use of substitute materials, and in spite of the tendency to utilize wood more economically. No sooner do substitutes take the place of wood in some particular place than new uses are found. A century ago railroad ties, rail road cars and telegraph poles had not been thought of. Now, American railroads alone use more lumber in a year than was re quired to meet all the needs of the 3o million people living in the United States in 1860. Newsprint and other products of wood pulp, automobiles, phonographs, radio cabinets and many other articles requiring large quantities of wood, all have come into extensive use within a generation.

In Great Britain timber consumption has increased much more rapidly than has the population. In 1915 with the total national consumption nearly six times as great as in 1851, the requirements per capita were almost four times as great. Even in France with a practically stationary population, timber consumption was slowly increasing until 1914; that of Germany more than doubled within the century; in the United States at least seven times as much lumber is now used in a year as in 1850, and even the per capita rate of consumption is considerably larger. Judging from the rates of increase in these and other important countries, the world's timber needs may be expected to double within approxi mately so years.

North America, with one-twelfth of the world's inhabitants, uses nearly half of all the timber and more than half of all the sawtimber. Its per capita consumption (188 cubic feet) is five times as great as that of Europe, and if the tropical countries south of the United States, all of which have a very low consump tion, be left out it is six and one-half times that of Europe. Australia, South America and Europe use about equal amounts of wood per capita (39 cubic feet). The proportion of sawtimber to total amount of wood used, however, is quite different, being only one-ninth in South America, two-fifths in Australia and over one-half in Europe. Asia and Africa use comparatively small amounts of wood (9 and 5 cubic feet, respectively), and most of what they do use is for fuel. (See Table II.) The Amount of Wood Grown in the World.—The total quantity of wood grown in the world each year is roughly esti mated at about 38 billion cubic feet. If this increment were spread evenly over the whole forest area, it would amount to only 5.1 cu.ft. per acre. It is apparent that the present annual growth of 38 billion cu.ft. is not replacing the present annual cut of 56 billion cubic feet. As a matter of fact, the amount of growth each year represents the growth of only a small part of the forest. Vast areas of virgin tropical forests, as well as much of the virgin forests of the temperate regions, must be left out of the calculation, because in their present condition there is no net growth in them. Twenty-two billion cubic feet, or more than half of the growth that is actually taking place at the present time, is in the forests of Europe, a large proportion of which are under management for the production of timber. If all the forests of the world were placed in a growing condition, even without much care of them beyond a moderate amount of protec tion against devastation, they could produce annually at least 355 billion cu.ft. of wood, or nearly so cubic feet per acre. Under intensive management the growth would be much greater.

The World Trade in Wood.

The total value of the world's export of all forest products, before the World War, amounted to about $1,063,400,000 or 5.6% of the total foreign trade of the world. The foreign trade in forest products during the last decade before the war showed a tendency to rapid increase, exceeding in some items the general rate of increase of the world trade. The entire world export from 1899 to 1911 increased 8o% in value. The trade in wood pulp, at the same time, showed an increase of 33o%; the trade in rubber and other chemical products of tropical forests showed even a greater rate of increase.Of the total trade in forest products, sawn, round, planed and split timber formed about 44% of the value of all exported forest products. Rubber, balsams and similar forest by-products, made up about 26% of the export; paper and wood pulp, and cellulose, 20% of the world's foreign trade; wooden furniture, toys and similar mechanically manufactured wood products, 8% ; the export of tropical cabinet woods, such as mahogany, ebony and others, 2 per cent. This did not include the trade in many edible products of the forests, such as vegetable oils, nuts, etc. Of the total volume of trade in wood products, about 8o% are composed of conifers, principally for construction and paper pulp. The temperate hard woods, used for staves, railroad ties, furniture, finish, cabinet work and other special purposes, constitute about 18%, while tropical hardwoods are only 2% of the total.

The Crux of the World's Timber Supply.

With about 51 billion acres of actually productive forest area in the world, much of it bearing heavy stands of virgin timber and with a possible annual growth many times the world's present timber require ments, it would seem that there is enough timber to last for cen turies. This would be true if all kinds of wood were equally capa ble of satisfying human wants. There are about 2,645,000,000 acres of softwoods or conifer forests in the world; some 1,204,000,00o acres of temperate hardwoods or broad-leaf forests, and 3,638,000,00o acres of tropical hardwoods. Although the softwoods and temperate hardwood forests form only one-half of the total forest area of the world, qi % of all the timber cut and used in the world comes from the softwood and temperate hardwood forests of the northern hemisphere, and only 9% from the tropical hardwoods. The softwood forests are furnishing three f ourths and the temperate hardwoods one-fifth of the construc tion timber of the world. The temperate hardwoods, in addition, supply three-fourths of all the firewood.The amount of standing timber in the tropics is far greater than the amount remaining in the temperate regions, yet until recently, the tropical forests have played a minor part in supply ing the world's timber. Until recently there has been prevalent an idea in the northern hemisphere that the tropical forests are composed chiefly of cabinet woods, such as mahogany, ebony, boxwood and satinwood, or dyewoods, such as logwood and brazil wood, and similar kinds of hard, heavy, deeply colored wood, possibly suitable for furniture and a few special uses but not for construction. Recent explorations have dispelled considerably this belief. It is known now that there are many excellent con struction woods, equal if not superior to the woods of conifers for use in the tropics because more resistant to decay and termites. It will be a great many years, however, before the tropical forests are able to supply a large part of the world's requirements for wood, if they ever can. Before they can do this, they must be opened up by adequate systems of cheap transport and adequate supplies of efficient labour must be at hand, both to construct the transportation facilities and to exploit the timber. This means a fairly large population of races accustomed to or easily adapt able to carrying on woods work on a large scale.

Another difficulty which must be overcome is the nature of the tropical forests themselves. They are mostly composed of a very great variety of species, intermingled in the greatest con fusion, and can be exploited economically only if practically all the important species can be utilized. Only a few of them are now known on the world's markets, and those are chiefly cabinet woods, of which the supply and possibilities for utilization are more or less limited. In order to dispose in the general market of large quantities of the less known timbers, particularly those which are more suited for common lumber and construction, a long process of education and economic pressure will be neces sary to overcome the established habits and idiosyncrasies of the consuming nations. Meanwhile, the timber requirements of the tropical countries themselves will doubtless grow as their indus tries develop, while their most accessible forests will probably be destroyed or rendered less productive, just as has happened in other regions passing through a corresponding stage of devel opment.

The crux of the world's timber supply problem, during the next two or three generations at least, lies in the available supplies of softwood and temperate hardwood forests, especially of the softwoods.

Softwood Supplies.

The softwood forests are confined to the cooler regions of the northern hemisphere. Although some conifers occur in the southern hemisphere, such as the Parana pine of Brazil, the alerce, pino, and cipres of Chile, the cedar and yellow-wood of Africa, the pines of the East and West Indies, and the kauri and other softwoods of New Zealand, they do not occur in sufficient abundance, however, to become important beyond their own regions. The present growth of conifer timber is not quite 8o% of the present cut. It is evident, therefore, that the forest capital is being steadily depleted.The principal conifer regions are (z) North America, including Canada, the United States, and the Sierras of Mexico; (2) north ern Europe and central Europe; (3) Asiatic Russia, Manchuria, and part of Japan.

In Canada the total amount of accessible merchantable saw timber is estimated at approximately 61.1- billion cubic feet and of pulpwood 52 billion cubic feet. The forests are being destroyed from two to two and one-half times faster than they are being grown. Taking an annual drain upon the forests of 5 billion cu.ft., the accessible stands of virgin forests will be exhausted in about 25 years. Canada uses now three-fifths of the lumber she pro duces and as her population grows her lumber requirements may be expected to increase also. The Canadian supply of pulpwood, although large, is already giving so much concern that the exporta tion of unmanufactured wood is subject to restriction in several provinces.

In the United States roughly only 385 billion cubic feet of softwoods of sawtimber size remain. Softwoods comprise two thirds of the 13 billion cu.ft. of large timber used annually and more than three-fourths of the sawed lumber. Nine-tenths of the paper consumed in the United States is made of softwoods. The United States now exports about 2 billion board feet of softwood timber annually, or about 7% of the amount cut. Almost as much is imported, however, so that the net export is only about one per cent of the production. To meet its present requirements, the United States is cutting about four times as much as it grows each year. Alaska has great reserves of virgin timber in her coast forests and when fully developed will contrib ute large quantities to the world trade.

Mexico has about 202 billion cu.ft. of pine in her mountainous forests at an elevation between 7,000 and io,000 feet. These mountainous forests have so far been able to withstand the primi tive hand-lumbering methods and ox and mule transportation over poor roads or pack trails. They will melt away, however, quickly before the attack of modern steam power logging and milling equipment backed by rail connections to the consuming centres of Mexico and the United States. Mexico may, therefore, in the near future export considerable quantities, at least for a few decades. Her own requirements are bound to grow, however, and at present she imports a great deal of pine lumber.

However, Europe as a whole is barely self-sufficient in meeting its needs for softwood timber. Western Europe depends upon imports to meet a large part of its present needs in softwoods. Just before the World War Great Britain imported 97% of the timber she consumed; France, Germany, Italy, Belgium, and the Netherlands imported approximately 30, 47, 65, 77 and 82% respectively. The only European countries that have any prospect of increasing their output of softwood timber for any consider able period or even of continuing to export at the present rate are Sweden, Finland, Russia, and possibly Czechoslovakia and Yugoslavia. Should Russia increase her own home consumption of timber, as is apparently inevitable with the rising standard of living of her population, Europe may be compelled to seek addi tional sources of softwood supplies from North America or Asia.

In Asia the only country exporting on a fairly large scale at present is Japan. Within a few years even Japan will need all her timber and may have to import some in addition. In Asia only western and eastern Siberia are reputed to have enormous supplies of virgin softwood timber. Siberian forests, however, are largely unexplored, and little is known of their actual con dition. According to rough estimates of the potential production of her forests, Siberia can furnish to the world market about 6 billion cu.ft. of softwood timber a year, which is double the quantity now entering international trade and 3o% of the world's consumption of conifer sawtimber.

Of the vast forest area of South America only 5% is composed of conifers. The bulk is in the Parana pine region of southern Brazil and adjacent portions of Argentina and Paraguay. Southern Chile, Paraguay and northern Argentina, the heaviest wood-con suming districts of South America, may be expected to take prac tically the entire output of Parana pine. At present the entire region produces only from one-third to one-half as much softwood timber as Argentina alone buys from the United States and Canada. The other South American countries depend upon the northern hemisphere for a considerable portion of their construc tion timber, although most of them have extensive forests of tropical hardwoods.

Africa, although it possesses extensive equatorial forests, does not contain enough softwood timber to furnish even the small amounts required locally for construction purposes. African countries import nearly all of their softwoods from Europe and North America.

In Australia, the softwood supply is inadequate for local needs. Much pine, fir and spruce lumber is imported from North Amer ica, Europe, and north-eastern Asia. The small area of softwood forest in New Guinea and the other islands of the Pacific is insignificant from the standpoint of the world supply.

Lord Lovat, after a survey of the softwood forests of the world, arrives at the conclusion that, except in Russia, the main softwood virgin timber reserves will be exhausted before very long, and Europe will have to depend more and more on timber raised by the agency of man ; that the United States shortage is likely to come more quickly than the European one ; that the more the American supply becomes centred in the Pacific Coast states, the greater is the probability of the industrial states of north-eastern America coming into European markets for saw timber in the same way that they do now for pulpwood ; and, finally, that as the United States consumes over 13 billion cu.ft. of softwoods, as opposed to a total European consumption of 9 billion cu.ft., the United States advent into European markets will have an important bearing upon European prices.

There are, however, several hopeful factors in the situation. The potential growth of the existing conifer forests, if they could be put under careful management, is probably three times the present cut. In most countries, possessing coniferous forests, the appreciation of their value and economic significance is becoming general and will undoubtedly prove a powerful factor in maintain ing them permanently in a condition to supply the world's needs.

Temperate Hardwood Supplies.

Like the conifers the tem perate hardwoods are confined chiefly to the northern hemisphere and are located fairly close to consuming centres. They as a rule occupy the better soils of the more favourably situated lands and, therefore, have been progressively destroyed to make room for cultivation. The large old timber has been depleted even to a greater extent than that of the softwoods.Europe has still extensive areas of hardwood forests and even exports special kinds, such as the oak of Poland and Slavonia. On the whole, however, the consumption of hardwoods in Europe greatly exceeds the production, so that there is a net annual im portation of about a hundred million cubic feet.

In Asia, Japan exports small quantities of oak. Walnut and other hardwoods are exported from Asiatic Turkey and the Cas pian region. Siberia has about 30%, by area, of the temper ate broad-leaved forests of the world. Except in the Far East, however, they consist of fairly light stands of aspen and birch, much of it valuable chiefly for firewood or pulp and not to be compared with the oak, ash, birch, maple, beech and other hard woods of the United States and Europe.

In North America the United States now has the largest supply of temperate hardwoods. The other North American countries have no surplus over their own needs. For many years the United States has been the largest exporter of high grade hardwoods. Now the original stand of approximately 2 5o billion cu.ft. of mer chantable hardwoods has dwindled to about one-fourth of that amount and is being further depleted at the rate of over two billion cu.ft. a year. The United States uses nearly four billion cu.ft. of hardwood timber a year, exclusive of firewood, or almost two-thirds of the entire world consumption of temperate hard wood timber.

In the temperate region of the southern hemisphere including southern Chile and Argentina, portions of New Zealand and Tas mania, and the high mountains of South America and Africa, are only relatively small quantities of valuable hardwood timber, little or none of it available for export.

The outlook for future supplies of hardwoods, however, is probably better than for softwoods, because woods adapted to the same uses can be got from the tropical forests, though they may cost considerably more.

Forestry as a Science.

Forestry, which is the science and art of growing timber, is a child of necessity. As long as forests are plentiful, they are exploited without thought for their renewal. It is only when forests become scarce and their complete exhaustion threatens that efforts are put forth toward their perpetuation. Forests, unlike mines, can be renewed. They are the product of the soil and, therefore, can be regrown like any other crop. The science underlying the growing of timber crops is, therefore, nothing but a branch of general plant science. Like agriculture, forestry is built on the foundations of plant science, soil science, and the science of the atmosphere (meteorology). The science of forestry comprises all the knowledge regarding forest growth,— its component parts, the life history of the species and their be haviour under varying conditions, their development and depend ence upon natural conditions, the forest's retroactive influence upon those natural conditions—in short, the forest's place in the economy of nature and man.Forestry, however, has characteristics which set it apart from other plant sciences. Forestry, unlike horticulture or agriculture, deals with wild plants scarcely modified by cultivation. Trees are also long-lived plants ; from the origin of a forest stand to its ma turity there may pass more than a century. Forestry, therefore, operates over long periods of time. It must also deal with vast areas. The soil under the forest is as a rule unchanged by culti vation, and most of the cultural operations applicable in arboricul ture or agriculture are entirely impracticable in forestry. Forestry is thrown back upon the same resources for maintaining the soil fertility as nature does. Forestry must make the forest itself con serve not only the fertility of the soil but even improve it. It does it by maintaining a certain density of stand, by regulating the density of the crowns, by creating an undergrowth, by controlling the composition and the form of the forest. The mechanical tilling of the soil is assigned to the roots of the forest trees and the fauna of the soil. The fertilizing of the soil is assumed by the trees in the stand. They, by shedding their foliage, supply the soil with a continual reservoir of material from which humus is made. The drying out of the soil is also ac complished with the aid of the stand itself. Forestry as a science must learn how to use the forest itself as an apparatus for the ac cumulation, conservation and in telligent use of moisture in the soil. The relation between forest and soil is much closer and deeper in forestry than in agri culture. Aside from the soil, the forester must know also the sub soil to a much greater extent than the agronomist because the roots of the forest trees often go very deep into the ground.

Forests are largely the product of nature, the result of the free play of natural forces. Since the forester had to deal with natural plants which grew under natural conditions, he early learned to study and use the natural forces affecting forest growth. In nature, the least change in topog raphy, exposure, depth of soil, etc., means a change in the com position of the forest, in its density, in the character and humid ity of the ground, and so on. For these reasons, forestry, although it is based like agronomy chiefly on plant physiology, is more closely related to oecology because intelligent management of the forests must be based on a thorough understanding of the rela tionships which exist between forests as living plants and their environments. Forestry may even be defined as applied oecology.

Forestry as an Art.

Like agriculture forestry is concerned in the use of the soil for crop production. As the agriculturist is en gaged in the production of food crops, so the forester is engaged in the production of wood crops, and finally both are carrying on their art for the practical purpose of revenue. If forestry as a science furnishes us the reason for forest practice—the why, forestry as an art teaches us how to apply our knowledge to the growing of timber. Two principles underlie the practice of forestry as opposed to forest exploitation : (I) the continuity of timber production or sustained yield ; this means that the cut in the long run should always equal the growth in the forest ; and (2) that the harvesting of the forest and its renewal should be nearly identical operations. In other words, the conditions for the re growth of . the forest should be provided for in the manner in which the forest is cut. The specific methods of accomplishing this naturally vary with the character of the forest, the species involved, the soil, and the kind of forest products to be grown.The entire field of forestry, both theoretical and applied, may be subdivided as follows.

Forest Production—continued Scientific Basis—continued Application—continued istry—meteorology and cli- 3. Forest mensuration.

matology with reference to Methods of ascertaining vol forest growth. umes and rates of growth of 3. Forest zoology. trees and stands and deter 4. Forest mathematics. mining yields. Algebra—trigonometry—ana- 4. Forest surveys.

lytical geometry—graphics— Area and boundary—topog statistical or biometric analy- raphy—ascertaining f or e s t sis, conditions—establishing units of management and adminis tration.

5. Forest valuation and finance. Ascertaining money value of forest property and financial results of different methods of management.

6. Forest regulation.

Preparing working plans— determining cutting budgets —organizing for continuous revenue and wood produc tion, and the utilization of secondary forest products, such as naval stores, forage, fish and game.

7. Forest administration. Organization of forest serv ices ; business practice and routine, including forest law and business law applicable to forest practice.

Forest Utilization Scientific Basis Application I. Timber physics. I. Wood technology.

Structure —physical and Application of wood in the chemical properties of wood, arts —requirements—working factors affecting them—dis- properties—use of minor and eases, faults and abnormali- by-products—preservation.

ties. 2. Harvesting of timber crops.

Methods of harvesting, trans porting and preparing for market.

Forest Economics Scientific Basis Application I. Political economy. I. Forest policy.

The place of forests and for- Formulating rights and duties estry in the economic life of of the states—forest legisla the nation. tion—state forest administra 2. Land economics. tion—education.

3. Forest statistics.

Areas: forest conditions—dis tribution—comp ositio n— ownership. Products: trade— supply and demand—prices substitutes.

4. History of forestry.

Forestry is not a new science. Systematic forest management existed already in France and Germany at the beginning of the 18th century and crude prescriptions as to the proper use of forests even date back to the 14th century. In Germany the first courses in forestry were organized between 1770 and 1780 at the universities of Leipzig, Jena, Giessen, and Berlin. In France the first forest institute was opened in 1824 at Nancy. To-day every civilized country has at least one forest school and often several. In the United States alone there are over 22 forest schools. Both Europe and the United States have now a net of forest experi ment stations at which, as at the agricultural experiment sta tions, the science of forestry is being advanced and new and better methods of forest management being constantly developed. Yet, if one considers that a mere I o or 15% of the world's forests is being handled as a renewable, continuously productive resource, while an additional 15 or 20% is more or less protected from de struction, but still regarded as a timber mine, and the greater part, from 65 to 75%, receives no care whatever, forestry is barely on the threshold of its greatest development.

Schlich, A Manual of Forestry (London) ; B. E. Fernow, Economics of Forestry (New York) ; Raphael Zon, Forests and Water in the Light of Scientific Investigation (U.S. Gov ernment Printing Office, Washington, D.C., 192 7) ; Raphael Zon and W. N. Sparhawk, Forest Resources of the World (New York, 1923), 2 vol.; Augustine Henry, Forests, Woods, and Trees in Relation to Hygiene (1919) ; C. L. Peck, Forests and Mankind (1929) . (R.Z.)