Milling Processes

MILLING PROCESSES Milling processes may be conveniently divided into two stages, (I) the cleaning and conditioning of wheat and (2) the separa tion of husk from kernel. Stated in these terms, milling may appear to be a simple process; actually it is a complicated one and, although modern milling developments have been in the direc tion of simplification, the diagram or flow sheet of a large modern mill would probably be unintelligible except to those trained in the technics of milling. From the economic or technical point of view the amount added by milling to the value of the raw material is the measure of the merit of the work involved.

Wheat Cleaning and

extraneous mat ter found in wheat consists principally of other cereals, seeds of many kinds, shapes and sizes, stones, chaff, straw, dust and dirt (earth). To extract these, many devices are employed. Sieves of perforated metal can extract substances either larger or smaller than wheat. But wheats differ so much as to size and shape of berry that better instruments than sieves are also necessary. Cylinders covered on their inner side with holes of varying sizes bored in zinc provide means of making more precise separations. Discs so bored rotating in a body of wheat are also employed.Ascending currents of air capable of precise regulation are passed through descending showers of wheat, and carry away particles which by reason of their shape or compactness of particle can be so separated. Wheat is scoured and brushed in various ways. One well-known machine consists essentially of a cylinder, clothed on its inner side with emery ; beaters revolving on a shaft serve the double purpose of scouring the wheat against the emery surface and of passing it through the length of the cylinder.

Conditioning is an English term; in the United States a some what similar operation is called tempering. Essentially it means that the physical condition of any given wheat is adjusted so that optimum separations of husk from kernel can be made. Sometimes water is added; sometimes it is abstracted. Adjust ments must be made to suit the wheat under treatment, the con ditions as to atmosphere and milling machinery subsequently used, and the flours to be produced. The factors employed are water, time and temperature. The methods of conditioning are still in the process of evolution. The results obtained by condi tioning are mainly or wholly physical.

Grinding.

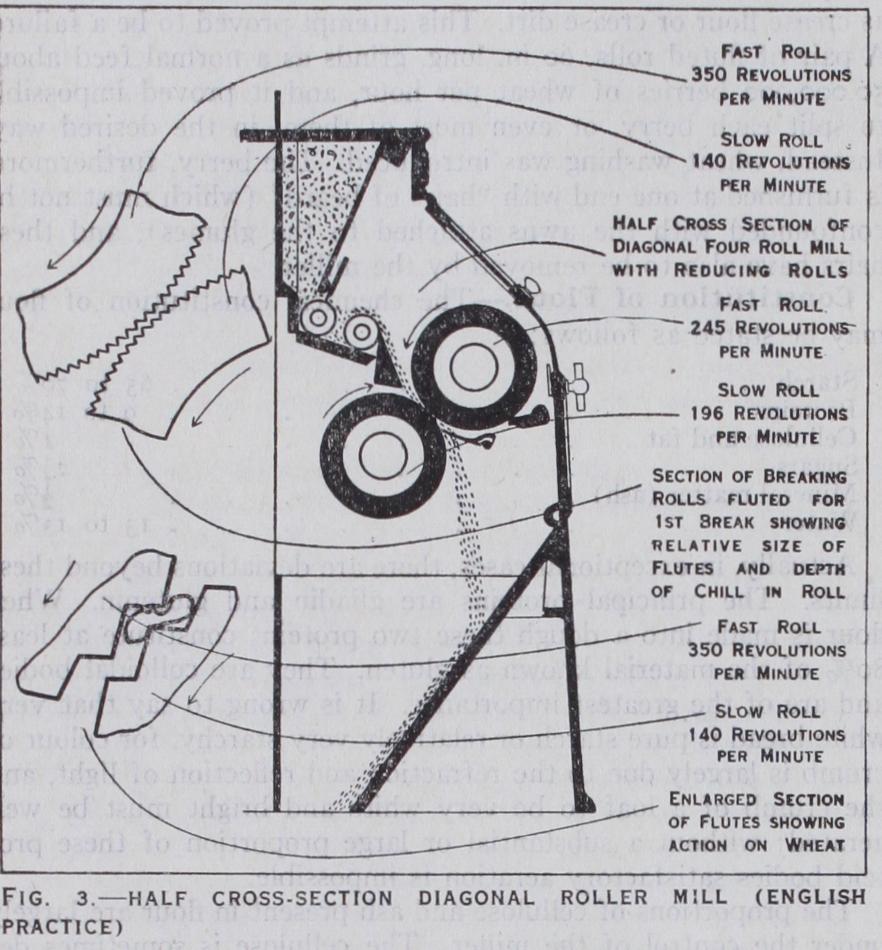

Roller mills are almost invariably employed for grinding to-day. When millers attempted at one operation to perform the whole of the grinding required, millstones were em ployed. This involved .the use of friction, very great in amount and intensity: one passage between millstones involved at least 4 ft. of rough handling. Even when the wheats used were soft or mellow and therefore relatively resistant to disintegration, some of the husk of the wheat was reduced to powder. The Hun garians grew wheat of excellent quality, but the grain was hard and its skin friable. They therefore began, about 6o years ago, to use roller mills. In other parts of Europe and in the eastern United States the wheats available were then mellow and the ne cessity for relatively gentle grinding was not great. But when the States of the north-west and the western provinces of Canada were developed, the varieties of wheat found to be suitable were hard and had friable skins. Hence the American millers adopted the new Hungarian methods and British millers were compelled to follow suit, for the ultimate users and consumers of flour would not accept flour or bread containing a large proportion of pow dered husk. For these reasons gradual reduction by roller mills superseded the sudden death methods of grinding wheat by mill stones.A pair of cylindrical rollers, running at the point of contact in the same direction, nip and grind their feed at one point only in their circumferences. But a release of endosperm particles from the branny husk, and not mere crushing, being the object desired, the two rolls forming a pair are made to revolve at differ ent speeds. This differential varies with the stage of milling. Furthermore, to effect optimum separations of husk from kernel it is necessary to obtain during the earlier stages of actual milling the endosperm particles in granular form. To effect this the rolls used in those stages are corrugated. The number and shape of these corrugations or flutes involve complicated technical points. The numbers range from 9 to 26 per in. of the roll's circum ference. Still further to improve the separations the flutes are cut at varying angles in relation to the rolls' axes.

In conformity with the principle of gradual reduction, no at tempt is made to obtain finished bran at one grinding; on the contrary, the wheat is broken down on the roller mills, known as the breaks, gradually by successive stages. These now number three, four or five; occasionally in some parts of the world six are used. Generally, millers aim to make as little flour as possible on the breaks, but some is made. The commercial article known as bran is separated from the stock, leaving the last break. The breaks as a stage of the milling process yield as finished products flour equalling from 8% to 18% of the original cleaned wheat and bran equalling from to of it. The remainder exists at that stage as granular products, known as middlings and semolina. These contain particles of pure endosperm, particles of pure husk and other particles consisting of endosperm with husk attached. The means of separating these constituents will be described in a succeeding paragraph.

Ultimately, to resolve these intermediate products into fin ished flour and finished husk (known commercially in Great Britain as offals and in North America as feed) further grinding by rolls is required. These are known technically as reduction rolls or reductions, and generally have either smooth surfaces or very fine flutes ranging from 7o to 120 per in. of the roll's circumference. The speed and differential are adjusted to the work to be done, but the principle of gradual reduction is em ployed at these stages also. The central idea of such grinding is a release of endosperm particles from husk. In the case of par ticles consisting of endosperm only, it is desirable to reduce them in size by grinding. In no case should granular particles, how ever fine, be merely crushed.