National Flags

NATIONAL FLAGS British.—The royal standard of Great Britain now bears the arms of England quartered with those of Scotland and Ireland. From the time of Richard I. it had borne the arms of England only, until Edward III. began to set the old arms of France in the first and fourth quarters with those of England in the second and third. Following the custom of the French king, Henry V. reduced the number of his fleurs-de-lis to three. The next change was made when James I. had the first and fourth quarters of France quartered with England, the second quarter of Scotland and the third of Ireland. William III. set over all this an escutch eon of Nassau, Queen Anne's first and fourth quarters were of England parted with Scotland, the second quarter of France, the third of Ireland. George I. showed the same, changing the fourth quarter for the arms of the electors of Hanover. In i 8o r the arms of the royal banner or standard were as they are now, save for Hanoverian arms on an escutcheon in the middle, which was removed at the accession of Queen Victoria. It is worthy of note, however, that in the royal standard of King Edward VII. which hangs in the chapel of St. George at Windsor, the ordinary "winged woman" form of the harp in the Irish third quartering is altered to a harp of the old Irish pattern.

Up to the time of the Stuarts it had been the custom of the lord high admiral or person in command of the fleet to fly the royal standard as deputy of the sovereign. When royalty ceased to be, a new flag was devised by the council of State for the Commonwealth, which comprised the "arms of England and Ireland in two several escutcheons in a red flag within a compartment." In other words, it was a red flag containing two shields, the one bearing the cross of St. George, red on a white ground, the other the harp, gold on a blue ground, and round the shields was a wreath of palm and shamrock leaves. One of these flags is still in existence at Chatham dockyard, where it is kept in a wooden chest which was taken out of a Spanish galleon at Vigo by Admiral Sir George Rooke in 1704. When Cromwell became Protector of the Commonwealth of England, Scotland and Ireland, he devised for himself a personal standard. This had the cross of St. George in the first and fourth quarters, the cross of St. Andrew, a white saltire on a blue ground, in the second, and the Irish harp in the third. His own arms—a lion on a black shield—were imposed on the centre of the flag. No one but royalty has a right to fly the royal standard, and though it is constantly seen flying for purposes of decoration its use is irregular. There has, however, always been one exception, namely that the lord high admiral when in executive command of a fleet has always been entitled to fly the royal standard. For example, Lord Howard flew it from the mainmast of the "Ark Royal" when he defeated the Spanish Armada; the duke of Buckingham flew it as lord high admiral in the reign of Charles I., and the duke of York fought under it when he commanded during the Dutch Wars.

The national flag of the British empire is the Union Jack in which are combined in union the crosses of St. George, St. Andrew and St. Patrick. St. George had long been a patron saint of England, and his banner of silver with a cross gules its national ensign. St. Andrew in the same way was the patron saint of Scotland, and his banner of azure with a saltire silver the national ensign of Scotland. On the union of the two crowns James I. issued a proclamation ordaining that "henceforth all our subjects of this Isle and Kingdom of Greater Britain and the members thereof, shall bear in their main-top the red cross commonly called St. George's cross, and the white cross commonly called St. Andrew's cross, joined together according to a form made by our heralds, and sent by us to our admiral to be pub lished to our said subjects; and in their fore-top our subjects of south Britain shall wear the red cross only, as they were wont and our subjects of north Britain in their fore-top, the white cross only as they were accustomed." This was the first Union Jack, as it is generally termed, though strictly the name of the flag is the "Great Union," and it is only a "Jack" when flown on the jackstaff of a ship of war. At the death of Charles I., the union with Scotland being dissolved, the ships of the parlia ment reverted to the simple cross of St. George, but the union flag was restored when Cromwell became protector, with the Irish harp imposed upon its centre. On the Restoration, Charles II. removed the harp and so the original union flag was restored, and continued as described until the year i 8oi, when, on the legislative union with Ireland, a cross styled like that of St. Pat rick, a saltire gules, in a field silver, was incorporated in the union flag. So to combine these three crosses without losing the dis tinctive features of each was not easy ; each cross must be distinct, and retain equally distinct its fimbriation, or bordering, which denotes the original ground. In the first union flag, the red cross of St. George with the white fimbriation that represented the original white field was simply imposed upon the white saltire of St. Andrew with its blue field. To place the red saltire of St. Patrick on the white saltire of St. Andrew would have been to obliterate the latter, nor would the red saltire have its proper bordering denoting its original white field ; even were the red saltire narrowed in width the portion of the white saltire that would appear would not be the St. Andrew saltire, but only the fimbriation appertaining to the saltire of St. Patrick. The diffi culty has been got over by making the white broader on one side of the red than the other. In fact, the continuity of direction of the arms of the St. Patrick red saltire has been broken by its portions being removed from the centre of the oblique points that form the St. Andrew's saltire. Thus both the Irish and Scottish saltires can be distinguished easily from one another, whilst the red saltire has its due white fimbriation.

The Union Jack is the most important of all British ensigns, and is flown by representatives of the empire all the world over. It flies from the jackstaff of every man-of-war in the navy. When flown by the governor-general of India the star and device of the order of the Star of India are borne in the centre. Colonial governors fly it with the badge of their colony displayed in the centre. Diplomatic representatives use it with the royal arms in the centre. As a military flag, it is flown over fortresses and headquarters, and on all occasions of military ceremonial. Hoisted at the mainmast of a man-of-war it is the flag of an admiral of the fleet.

Military flags in the shape of regimental standards and colours, and flags used for signalling, are described elsewhere, and it will here be only necessary to deal with the navy and admiralty flags.

The origin of the three ensigns—the red, white and blue— had its genesis in the navy. In the days of huge fleets, such as prevailed in the Tudor and Stuart navies, there were, besides the admiral in supreme command, a vice-admiral as second in command, and a rear-admiral as third in command, each con trolling his own particular group or squadron. These were designated centre, van, and rear, the centre almost invariably being commanded by the admiral, the vice-admiral taking the van and the rear-admiral the rear squadron. In order that any vessel in any group could distinguish its own admiral's ship, the flagships of centre, van, and rear flew respectively a plain red, white, or blue flag, and so came into being those naval ranks of admiral, vice-admiral and rear-admiral of the red, white and blue which continued down to as late as 1864. As the admiral in supreme command flew the union at the main, there was no rank of admiral of the red, and it was not until Nov. i 8o5 that the rank of admiral of the red was added to the navy as a special compliment to reward Trafalgar. About 1652; so that each individual ship in the squadron should be distinguish able as well as the flagships, each vessel carried a large red, white or blue flag according as to whether she belonged to the centre, van, or rear, each flag having in the left-hand upper corner a canton, as it is termed, of white bearing the St. George's cross. These flags were called ensigns, and it is, of course, due to the fact that the union with Scotland was for the time dissolved that they bore only the St. George's cross. Even when the restoration of the Stuarts restored the status quo the cross of St. George still remained alone on the ensign, and it was not altered until 1707 when the bill for the Union of England and Scotland passed the English parliament. In 18o1, when Ireland joined the Union, the flag, of course, became as we know it to-day. All these three ensigns belonged to the royal navy, and continued to do so until 1864, but as far back as 1707 ships of the mercantile marine were instructed to fly the red ensign. As ironclads replaced the wooden vessels and fleets became smaller the inconvenience of three naval ensigns was manifest, and in 1864 the grades of flag officer were reduced again to admiral, vice-admiral, and rear-admiral, and the navy abandoned the use of the red and blue ensigns, retaining only the white ensign as its distinctive flag. The mercantile marine retained the red ensign which they were already using, whilst the blue ensign was allotted to vessels employed on the public service whether home or colonial.

The white ensign is therefore essentially the flag of the royal navy. It should not be flown anywhere or on any occasion except by a ship (or shore establishment) of the royal navy, with but one exception. By a grant of William IV. dating from 1829 vessels belonging to the Royal Yacht Squadron, the chief of all yacht clubs, are allowed to fly the white ensign. From 1821 to 1829 ships of the squadron flew the red ensign, as that of highest dignity, but as it was also used by merchant ships, they then obtained the grant of the white ensign as being more distinctive. Some few other yacht clubs flew it until 1842, when the privilege was withdrawn by an admiralty minute. By some oversight the order was not conveyed to the Royal Western of Ireland, whose ships flew the white ensign until in 1857 the usage was stopped. Since that date the Royal Yacht Squadron alone has had the privilege. Any vessel of any sort flying the white ensign, or pennant, of the navy is committing a grave offence, and the ship can be boarded by any officer of His Majesty's service, the colours seizad, the vessel reported to the authorities, and a penalty inflicted on the owners or captain or both. The penalty incurred is £500 fine for each offence, as laid down in the 73rd section of the Merchant Shipping Act, Besides the white ensign the ship of war flies a long streamer from the maintopgallant masthead. This, which is called a pen nant, is flown only by ships in commission; it is, in fact, the sign of command, and is first hoisted when a captain commissions his ship. The pennant, which was really the old "pennoncell," was of three colours for the whole of its length, and towards the end left separate in two or three tails, and so continued till the end of the great wars in 1816. Now, however, the pennant is a long white streamer with the St. George's cross in the inner portion close to the mast. Pennants have been carried by men of-war from the earliest times, prior to 1653 at the yard-arm, but since that date at the maintopgallant masthead.

The blue ensign is exclusively the flag of the public service other than the royal navy, and is as well the flag of the royal naval reserve. It is flown also by certain authorized vessels of the British mercantile marine, the conditions governing this privilege being that the captain and a certain specified portion of the officers and crew shall belong to the ranks of the royal naval reserve. When flown by ships belonging to British Govern ment offices the seal or badge of the office is displayed in the fly. For example, hired transports fly it with the yellow anchor in the fly ; the marine department of the Board of Trade has in the fly the device of a ship under sail; the telegraph branch of the post-office shows in the fly a device representing Father Time with his hour-glass shattered by lightning; the ordnance department displays upon the fly a shield with a cannon and cannon balls upon it. Certain yacht clubs are also authorized by special admiralty warrant to fly the blue ensign. Some of these display it plain ; others show in the fly the distinctive badge of the club.

Consuls-general, consuls and consular agents also have a right tc fly the blue ensign, the distinguishing badge in their case being the royal arms.

The red ensign is the distinguishing flag of the British merchant service, and special orders to this effect were issued by Queer Anne in 1707, and again by Queen Victoria in 1864. The order of Queen Anne directed that merchant vessels should fly a red flag "with a Union Jack described in a canton at the upper corner thereof next the staff," and this is probably the first time that the term "Union Jack" was officially used. In some cases those yacht clubs which fly the red ensign change it slightly from that flown by the merchant service, for they are allowed to display the badge of the club in the fly. Colonial merchantmen usually display the ordinary red ensign, but, provided they have a warrant of authorization from the admiralty, they can use the ensign with the badge of the colony in the fly.

There are two other British sea flags which are worthy of brief notice. These are the admiralty flag and the flag of the master of Trinity House. The Admiralty flag is a plain red flag with a clear anchor in the centre in yellow. In a sense it is a national flag, for the sovereign hoists it when afloat in conjunction with the royal standard and the Union Jack. It would appear to have been first used by the duke of York as lord high admiral, who flew it when the sovereign was afloat and had the royal standard flying in another ship. When a board of commissioners was appointed to execute the office of lord high admiral this was the flag adopted, and in 1691 we find the admiralty, minuting the navy board, then a subordinate department, "requiring and directing it to cause a fitting red silk flag, with the anchor and cable therein, to be provided against Tuesday morning next, for the barge belonging to this board." In 1725, presumably as being more artistic, the cable in the device was twisted round the stock of the anchor. It was thus made into a "foul anchor," the thing of all others that a sailor most hates, and this despite the fact that the first lord at the time, the earl of Berkeley, was himself a sailor. The anchor retained its unseamanlike appearance, and was not "cleared" till 1815, and even to this day the buttons of the naval uniform bear a "foul anchor." The "anchor" flag is solely the em blem of an administrative board; it does not carry the executive or combatant functions which are vested in the royal standard, the union or an admiral's flag, but on two occasions it has been made use of as an executive flag. In 1719 the earl of Berkeley, who at the time was not only first lord of the admiralty, but vice-admiral of England, obtained the special permission of George I. to hoist it at the main instead of the union flag. Again in 1869, when Childers, then first lord, accompanied by some members of his board, went on board the "Agincourt" he hoisted the Admiralty flag and took command of the combined Mediter ranean and Channel Squadrons, thus superseding the flags of the two distinguished officers who at the time were in command of these squadrons. It is hardly necessary to add that throughout the navy there was a very distinct feeling of dissatisfaction at the innovation. When the Admiralty flag is flown by the sovereign it is hoisted at the fore, his own standard being of course at the main, and the union at the mizzen.

The flag of the master of the Trinity House is the red cross of St. George on its white ground, but with an ancient ship on the waves in each quarter; in the centre is a shield with a precisely similar device and surmounted by a lion.

The sign of a British admiral's command afloat is always' the same. It is the St. George's cross. Of old it was borne on the main, the fore, or the mizzen, according as to whether the officer to whom it pertained was admiral, vice:admiral, or rear-admiral, but, as ironclads superseded wooden ships, and a single pole mast took the place of the old three masts, a different method of indi cating rank was necessitated. To-day the flag of an admiral is a square one, the plain St. George's cross. When flown by a vice admiral it bears a red ball on the white ground in the upper canton next to the staff ; if flown by a rear-admiral there is a red ball in both the upper and lower cantons. As nowadays most battleships have two masts, the admiral's flag is hoisted at the one which has no masthead semaphore. The admiral's flag is always a square one, but that of a commodore is a broad white pennant with the St. George's cross. If the commodore be first class the flag is plain; if of the second class the flag has a red ball in the upper canton next to the staff. The same system of differentiating rank prevails in most navies, though very often a star takes the place of the ball. In some cases the indications of rank are differently shown. For instance, in the Japanese navy the distinction is made by a line of colour on the upper or lower edges of the flag.

The flags of the British colonies are the same as those of the mother country, but differentiated by the badge of the colony being placed in the centre of the flag if it is the Union Jack, or in the fly if it be the blue or red ensign. Examples of these are shown in the Plate, where over the red ensigns illustrated is that of New Zealai,d, the device of the colony being the Southern Cross in the fly. The same flag, with the stars of the Southern Cross, seven-pointed instead of five-pointed, and the addition under the union of a large seven-pointed star emblematic of the six States and territories of the Commonwealth, and a small five pointed star in the Southern Cross, forms the flag of Australia. The merchant flag has the same device on a red ensign. An other red ensign shown is that of the Dominion of Canada, the device in the fly being the armorial bearings of the Dominion. As the viceroy of India, as representative of the King-Emperor, flies the Union Jack with the badge of the Order of the Star of India in the centre, so the Dominion or colonial governors or high corn missioners (except in the case of the Irish Free State) fly the Union Jack with the arms of the Dominion or colony they preside over on a white shield in the centre and surrounded by a laurel wreath. In the case of Canada the wreath, however, is not of laurel but of maple, which is the special emblem of the Dominion.

(H. L. S.) American.—The first flag flown in the British colonies in America was a square of white bunting or silk adorned with a large red cross of St. George, the arms of which extended to its full length and breadth. It was carried by John Cabot when he discovered the North American continent in 1497, and the ships that brought the colonists to Jamestown, Va., in 1607, and to Plymouth, Mass., in 162o, displayed it as a matter of course as it was the English flag.

The Puritans of New England objected to the cross and in 1634 John Endecott, governor of Massachusetts ten years later, cut part of the cross from the flag at Salem. Formal complaint was entered in November of that year that the flag had been de faced by Mr. Endecott and it was charged that the mutilation might be construed as an act of rebellion against England. When the case was tried it was testified that the mutilation had been done, not as an act of disloyalty, but from the conscientious con viction that as the cross had been given to England by the Pope it was a relic of Antichrist and that to allow it to remain was an act of idolatry. Endecott was found guilty of "a great offence" for which he was worthy of admonition and he was debarred from holding public office for a year.

When Sir Edmund Andros was commissioned as governor of New England in 1686 he designed a flag showing the cross of St. George on a white ground with the initials "J. R." signifying "Jacobus Rex" in the centre of the cross surmounted by a crown. The New England flag of 1737 was blue with the cross of St. George in the canton, with a globe in the upper left hand corner.

When the British took over New York from the Dutch in Sept. 1664, the flag of St. George's cross was displayed in place of the Dutch flag. Banners of many different designs were used by the different colonies. In the early days of the revolutionary struggle each State adopted a flag of its own. That of Massachu setts bore a pine tree. South Carolina had a flag adorned with a rattlesnake. The New York flag was white with a black beaver on it, and the Rhode Island flag was also white adorned with a blue anchor. The rattlesnake with 13 rattles was a common decoration usually accompanied by the inscription, "Don't tread on me." The snake and the motto appeared on the banner of John Proctor's battalion raised in Westmoreland county, Penn sylvania. It was carried by this battalion in the Revolutionary war. The regimental colours differed with the taste of their commanders.

The first flag containing the stars of which there is any record was hoisted in 1775 on the armed schooner "Lee," captain, John Manley, of Massachusetts. The flag was white with a blue canton containing 13 five-pointed stars. In the centre of the flag was a blue anchor at the top of which was a scroll bearing the word, "Hope." In Oct. 1775, while the English troops were besieged in Boston, it was concluded that there should be a flag representing all the colonies. A committee, of which Benjamin Franklin was chair man, was appointed to choose a design. It decided that the flag should contain 13 alternate red and white stripes with the crosses of St. George and St. Andrew of the Union Jack in the canton, to indicate loyalty to the Crown, as the colonies were protesting merely against taxation without representation and were not planning separation. This flag or standard was first flown at Washington's headquarters in Cambridge, Mass., on Jan. 2, 1776. It is known variously as the Cambridge, the Grand Union, and the Continental flag. The Committee of Safety at Philadelphia, on Feb. 24, 1776, ordered the commander of the fort there to get a flag staff with a flag of the united colonies, meaning the Cambridge flag.

When the British evacuated Boston in March 1776, two divi sions of continental troops marched in displaying the same flag, and on May 15, 1776, when the Virginia legislature adopted a resolution favouring separation from England, the flag with the Union Jack was flying from the capitol.

On July 3o, 1776, a British commander saw an American ship in the West Indies flying this flag and the same flag was found flying on the fort in New York when Lord Howe arrived with the English fleet. The colonies had declared their independ ence nearly two months before, but were still using the Cam bridge flag.

It was not until June 14, 1777, almost a year after the adop tion of the Declaration of Independence, that the Continental Congress adopted a design for the national flag. It resolved that "The flag of the United States shall be thirteen stripes, alter nate red and white, with a union of thirteen stars of white on a blue field, representing a new constellation." It was explained by a contemporary commentator that the blue in the field was taken from the edge of the Covenanters' banner of Scotland, significant of the covenant of the United States against oppression, that the arrangement of the stars in a circle symbolized the perpetuity of the Union, the ring signifying eter nity, and that the 13 stripes indicated the subordination of the States to the Union and their equality among themselves. The red was said to denote daring, and the white purity. The adop tion of this resolution was not officially announced until Sep tember 3, almost two months after its passage.

Although the 13 stars were first arranged in a circle, no rule for the way in which they should appear had been made. There was, therefore, no uniformity. Some flags were made with 12 stars in a circle and one in the centre, others with three horizon tal rows of four, five and four. In others the stars were arranged as if they had been placed on the arms of the combined crosses of St. George and .St. Andrew, one row horizontal and another per pendicular for the cross of St. George and two diagonal rows representing the cross of St. Andrew.

The importance of a flag for the ships which Congress had ordered to be fitted out in 1775 was recognized, and Washington wrote to Congress on October 20 of that year, suggesting that a flag be adopted so that the "vessels may know one another." The Massachusetts flag with the stars and blue anchor was favoured, but Congress took no action.

In Oct. 1776, William Richards, a quartermaster, wrote to the Committee of Safety in Philadelphia that the commodore of the fleet had complained about the lack of a flag and had said that he could not get one until a design was fixed. Yet the ships of the navy displayed the Cambridge flag after it had been hoisted on the staff at Washington's headquarters in Cambridge in Jan, 1776.

Although Congress adopted a design for the flag on June 14, 1777, that flag was not immediately used by the army, but the navy used it at once. When John Paul Jones took command of the "Ranger" in the summer of 1777 he hoisted the Stars and Stripes. This is supposed to be the first time it was displayed on an American naval vessel.

It has sometimes been said that the Stars and Stripes was first used in battle in the defence of Fort Stanwyx in New York in Aug. 1777, but the War department, after investigation, de cided that it was the Cambridge flag that was used.

What is believed to be the first flag in substantially its present form was carried in the battle of Bennington on Aug. 16, 1777. It has 13 alternate red and white stripes, and a blue canton con taining the number "76" in a semi-circle of i i seven-pointed stars with a 12th and 13th in the upper corners. It is preserved in the battle monument in Bennington. The design differs from that ordered by Congress as there are figures in the canton. The flag carried at the battle of the Brandywine on Sept. cor responded to the design ordered by Congress.

There does not seem to have been any uniformity in the de sign of the flags used by different sections of the army. In the late spring of 1779, nearly two years after Congress had acted, there was some correspondence between Washington and the War Office on the subject. The War Office wrote to Washington that it was intended that each regiment should have two colours, "one the standard of the United States which should be the same throughout the army, and the other the regimental colours which should vary according to the facings of the regiment." The letter further stated "that it is not yet settled what is the standard of the United States," and asked Washington for his views so that they might be transmitted to Congress with a request that it establish a standard.

There is no record of congressional action resulting from this correspondence, probably because it was discovered that action had been taken two years earlier. It has been suggested that the "standard" referred to was a battle flag distinct from the Stars and Stripes, but there is much contemporary evidence that "flag" and "standard" were used interchangeably with no distinction be tween them.

There has been much speculation about the origin of the design of the Stars and Stripes. There is no evidence to support the theory that it was suggested by Washington's coat of arms which contains stars and stripes. At the time the flag was designed there were several flags in Europe with red and white stripes, and the flag of the East India Company contained such stripes with the Union Jack in the corner.

The most recent investigators lean to the conclusion that the design was drawn by Francis Hopkinson, a member of the naval committee and a signer of the Declaration of Independence. He was an artist, and there are extant bills which he presented to Congress for artistic work.

The first public assertion that Elizabeth, or Betsy, Ross made the first Stars and Stripes appeared in a paper read before the Historical Society of Pennsylvania on March 14, 1870, by William J. Canby, a grandson.

His aunt, Clarissa Sidney Wilson, a daughter of Betsy by her third husband, had conducted the upholstery business of her mother after the latter's death, retired from business and moved from Philadelphia to Wisconsin in 1857. She asked her nephew at about that time to write from her dictation the story of the making of the flag which she had heard from her mother many times.

Several years later, Mr. Canby began to write out the story more fully and sought to verify it, but he found no record among the official documents of any action by Congress prior to June 14, when the design of the flag was approved. He told of the result of his investigations to the historical society.

The story which Betsy Ross told, as remembered by her daughter, was that at some time in June 1776, before the adoption of the Declaration of Independence, Gen. Washington, Robert Morris, and George Ross, an uncle of her first husband who had recently died, came to her upholstery shop in Arch street, Philadel phia,representing themselves as a committee of Congress, and asked her if she could make a flag. They had with them a rough draft of a flag with stars and stripes. The stars had six points. She suggested some modifications in the design and folded a piece of paper in such a way that with one cutting of the shears she made a five-pointed star. This was approved. Then Washington, according to the story, redrew the design. She made a flag which was taken to the State House, where Congress was in session, and exhibited to the members. They then adopted it as the flag of the United States, and ordered her to make a large number of them.

This story was long regarded as authentic, and on Dec. 19, 1898 the American Flag House and Betsy Ross Memorial Association were incorporated under the laws of Pennsylvania for the purpose of preserving the house in which the flag was supposed to have been made. Included among the incorporators were the governor of the State, the superintendents of public schools in Philadelphia and New York city, Gen. O. O. Howard, and many other men of high standing.

The house was bought from the proceeds of subscriptions by school children and others. It has been offered to the United States Government, to the State of Pennsylvania, and to the city of Philadelphia, but it has not been accepted for it has not been definitely proved that Mrs. Ross ever occupied what has come to be known as the Flag House at 239 Arch street. She is said to have lived either at or 241 Arch street according to the best information obtainable.

In The True Story of the American Flag by John H. Fow, pub lished in 1908, the truth of the Betsy Ross story is disputed and much evidence is presented in support of the assertion that it has no foundation in fact. In the following year appeared The Evo lution of the American Flag by Lloyd Balderston, in which the Betsy Ross story is told in detail and supported by affidavits from various descendants, who repeat in one form or another the ver sion given by Mr. Canby to the historical society.

There is no record of the appointment of a committee to design a flag in June 1776, and there is no record of the adoption of any design by Congress prior to June of the next year. The only record anywhere of the manufacture of flags by Mrs. Ross is in Harrisburg, Pa., in the shape of a voucher dated May 29, 1777, for 14 pounds and some shillings for flags for the Pennsylvania navy. The letter of William Richards to the Committee of Safety, months after the Betsy Ross flag was said to have been made, seems to discredit the story of her descendants.

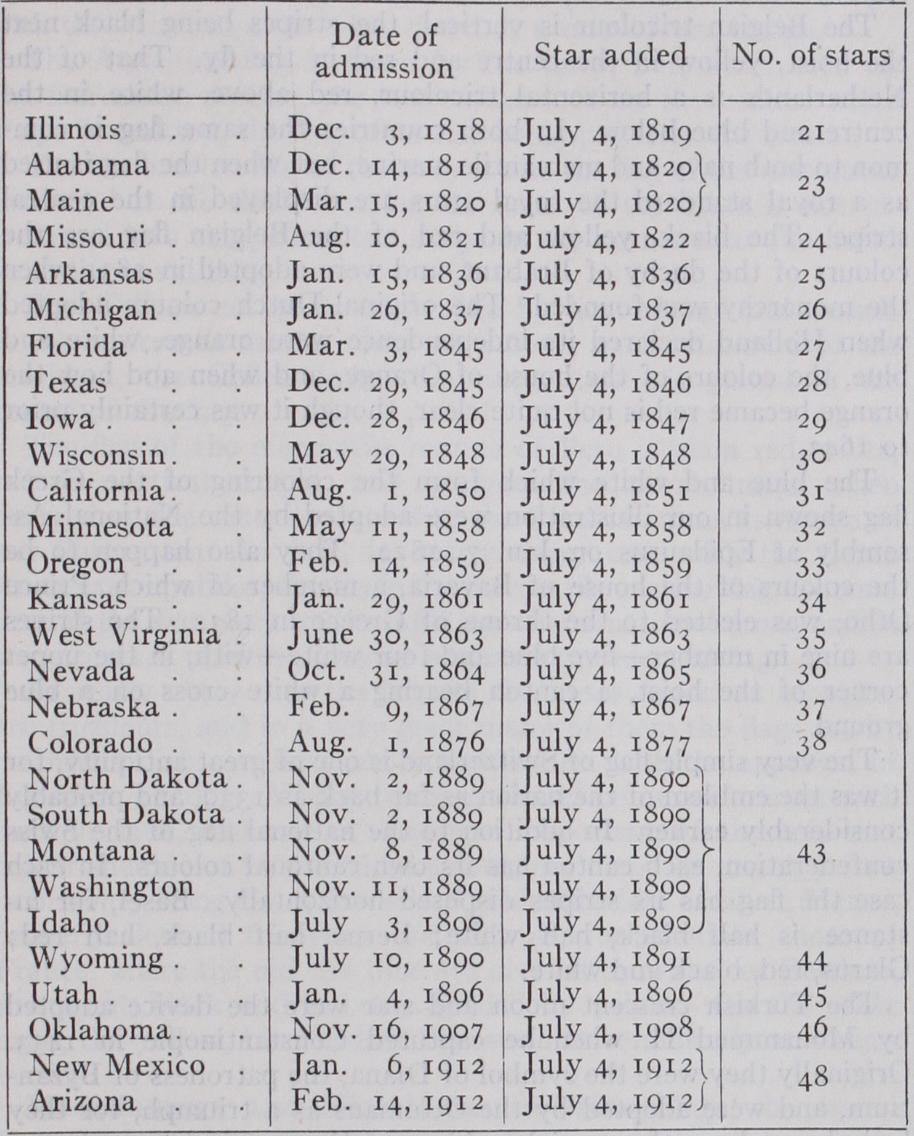

There was no change in the number of stars or stripes from the adoption of the design until Jan. 17, 1794, when Congress, in recognition of the admission of Vermont and Kentucky, voted to add two stripes and two stars, one for each of the new States. This design remained unchanged until 1818, when there were 20 States in the Union, and the prospect of the creation of more. It was evident that the addition of a stripe for each new State would make an unwieldy flag, so Congress on April 18 of that year voted that the flag should contain 13 alternate red and white stripes representing the original 13 States, and that a star should be added for each new State on July 4 following its admission. The flag thus ordered had 20 stars, Ohio, Louisiana, Indiana, and Mississippi getting their stars then for the first time. The follow ing table shows the date of admission of the other 28 States, the date of the addition of the star, and the number of stars follow ing each addition to the number of States.

Two stars were added on July 4, 1820, four on July 4, 1890-and two on July 4, In no other year save 1818, when the present design of the flag was finally fixed, was more than one star added.

There were 15 stars and 15 stripes on the flag at the time of the War of 1812. When the Mexican War began, the flag had 28 stars and when Fort Sumter was fired on in April 1861, the flag had 33 stars, but in July of that year the Kansas star was added, making 34, and before the Civil War ended the admission of West Virginia added another star, making 35. When war was declared against Spain on April 4, 1898, there were 45 stars but the number was increased to 46 on July 4, 1908, by the admission of Oklahoma.

The flag carried in the World War, in which the United States became involved in had 48 stars.

The President has a flag of his own which is displayed from the main of a ship on which he embarks. It is blue with the coat of arms of the United States in its proper colours at the centre.

The flag of the Secretary of the Navy is also blue, with a white fouled anchor in the centre surrounded by four white stars. The flag of the Secretary of War is scarlet, adorned with an eagle with outstretched wings.

The revenue flag, used to indicate the jurisdiction of the Secre tary of the Treasury, adopted in 1799, carries 16 perpendicular red and white stripes with the coat of arms of the United States in the canton extending over eight stripes.

The selection of a suitable flag was the subject of much dis cussion in the South when the slave States seceded from the Union. The States adopted flags of their own and there was an attempt to have one of them chosen. Many original designs were also proposed.

Early in Feb. 1861, a convention of six of the States met in Montgomery, Ala., to consider the form of government to be set up. While the committee was deliberating on this subject another committee was appointed to select a flag.

This committee examined the various designs and finally recom mended that "the flag of the Confederate States of America shall consist of a red field with a white space extending horizontally through the centre equal to one-third the width of the flag, the red spaces above and below to be of the same width as the white; the union blue, extending down through the white space and stopping at the lower space ; in the centre of the union a circle of white stars corresponding to the number of States of the Con federacy." This report was adopted on March 4, 1861. The flag thus ap proved came to be known as the Stars and Bars. It was first displayed over the State House in Montgomery.

At the battle of Bull Run, or Manassas as the Confederates called it, the similarity in colours of the flags of the Northern and Southern armies led to confusion and at the suggestion of Gen. G. T. Beauregard a battle flag was devised and used by the Southern armies throughout the war. It was based on a design suggested by Col. Miles and Col. Walton, and consisted of a red field on which was placed a blue St. Andrew's cross separated from the field by a white fillet, and adorned with white stars to the number of Confederate States. The Stars and Bars having proved to be unsatisfactory, demand was frequently made for the adoption of a flag of different design. Finally, in May 1863, the Confederate Congress, in session in Richmond, Va., adopted a new design.

The resolution recommending it set forth that the flag should be white, twice the length of the width and that the union should be a red square two-thirds the width of the flag, containing the battle flag designed by Gen. Beauregard. This flag seemed to be reasonably satisfactory. The only objection raised against it was that it resembled the white English ensign and might be mistaken for a flag of truce. In order to meet the latter objection it was ordered on Feb. 4, 1865, that a broad transverse strip of red be added to it.

(G. W. Do.) French.—To come to flags of other countries, nowhere have historical events caused so much change in the standards and national ensigns of a country as in the case of France. The oriflamme and the Chape de St. Martin were succeeded at the end of the i6th century, when Henry III., the last of the house of Valois, came to the throne, by the white standard powdered with fleurs-de-lis. This in turn gave place to the famous tricolour. The tricolour was introduced at the time of the Revolution, but the origin of this flag and its colours is a disputed question. Some maintain that the intention was to combine in the flag the blue of the Chape de St. Martin, the red of the oriflamme, and the white flag of the Bourbons. By others the colours are said to be those of the city of Paris. The tricolour is divided vertically into three parts of equal width—blue, white and red, the red forming the fly, the white the middle, and the blue the hoist of the flag. During the first and second empires the tricolour became the impe rial standard, but in the centre of the white stripe was placed the eagle, whilst all three stripes were richly powdered over with the golden bees of the Napoleons. The tricolour is now the sole flag of France.

Other Countries.

The most general and a few of the newest of the various national flags are figured in the Plate. Representing Great Britain are shown the royal standard and Union Jack (the national flag). The next line shows 4 other flags of Great Britain: the white ensign of the royal navy, the blue ensign of Govern ment service, and two red ensigns of the commercial marine, colonial flags being shown in the case of the three latter ensigns. The two Japanese flags shown are the man-of-war ensign—a rising sun, generally known as the sunburst—and the flag of the mercantile marine, in which the red ball is used without the rays and placed in the centre of the white field. The imperial standard of Japan is a golden chrysanthemum on a red field. It is essential that the chrysanthemum should invariably have 16 petals. Her aldry in Japan is of a simpler character than that of Europe, and is practically limited to the employment of Mon. The great families of Japan possess at least one, and in many cases even three, Mon.The imperial family uses two, the one Kiku no go Mon (the august chrysanthemum badge) and Kiri no go Mon (the august Kiri badge) .

The German imperial standard had the iron cross with its white border displayed on a yellow field, diapered over in each of the four quarters with three black eagles and a crown. In the centre of the cross was a shield bearing the arms of Prussia surmounted by a crown, and surrounded by a collar of the Order of the Black Eagle. In the four arms of the crown was the legend Gott mit uns 187o. The national flag of the German republic was a tricolour of three horizontal stripes—black, red and yellow. In Sept. the official flag was declared to be a black swastika in a white circle on a red ground.

In the U.S.A. and France men-of-war and the mercantile marine fly the same flag. Austria's national flag had three horizontal stripes. Red above, white in the centre and red below.

The green, white and red Italian tricolour was adopted in i8o5, when Napoleon I. formed Italy into one kingdom. It was adopted again in 1848 by the Nationalists of the peninsula, accepted by the king of Sardinia, and, charged by him with the arms of Savoy, it became the flag of a united Italy. The man-of-war flag is precisely similar to that of the mercantile marine, except that in the case of the former the shield of Savoy is surmounted by a crown. The royal standard is a blue flag. In the centre is a black eagle crowned and displaying on its breast the arms of Savoy, the whole sur rounded by the collar of the Most Sacred Annunziata, the third in rank of all European orders. In each corner of the flag is the royal crown.

For the Portuguese republic the flag is one of the few national flags that are parti-coloured. It is part green, part red, with, in the centre, the arms of Portugal.

In the Spanish ensigns red and yellow are the prevailing colours, and here again the arrangement differs from that generally used. The navy flag has a yellow central stripe, with red above and below. To be correct the yellow should be half the width of the flag, and each of the red stripes a quarter of the width of the flag. The central yellow stripe is charged in the hoist with an escutcheon containing the arms of Castile and Leon, and surmounted by the royal crown. In the mercantile flag the yellow centre is without the escutcheon, and is one-third of the entire depth of the flag, the remaining thirds being divided into equal stripes of red and yellow, the yellow above in the upper part of the flag, the red in the lower.

The flag of the Soviet Government in Russia (1929) is the red flag charged, in the upper quarter of the hoist, with a golden sickle crossed saltirewise with a golden hammer, a star (molet) above.

The flag of the Russian mercantile marine was a horizontal tricolour of white, blue and red. Originally, it was a tricolour of blue, white and red, and it is said that the idea of its colouring was taken by Peter the Great when learning shipbuilding in Holland, for as the flag then stood it was simply the Dutch ensign reversed. Later, to make it more distinctive, the blue and white stripes changed places. The flag of the Russian navy was the blue saltire of St. Andrew on a white ground. The imperial standard was of a character akin to that of Austria ; the ground was yellow, the centre bearing the imperial double-headed eagle, a badge that dates back to 1472, when Ivan the Great married a niece of Con stantine Palaeologus and assumed the arms of the Greek empire. On the breast of the eagle was an escutcheon charged with the emblem of St. George and the Dragon on a red ground, and this was surrounded by the collar of the order of St. Andrew. On the splayed wings of the eagle were small shields bearing the arms of the various provinces of the empire.

The Rumanian flag is a blue, yellow and red tricolour, the stripes vertical, with the red stripe forming the fly. Yugoslavia, the new kingdom of the Serbs, Croats and Slovenes has a horizontal tricolour, the top stripe blue, the middle white and the lower red. The Bulgarian flag is a similar tricolour, white, green and red, the white stripe uppermost.

The flags of all the three Scandinavian kingdoms are some what similar in design. That of Denmark, the Dannebrog, has been already alluded to, and it is shown in our illustration as flown by the Danish navy. The mercantile marine flag is pre cisely similar, but rectangular instead of being swallow-tailed. The Swedish flag is a yellow cross on a blue ground. When flown from a man-of-war it is forked as in the Danish, but the longer arm of the cross is not cut off but pointed, thus making it a three pointed flag as illustrated. For the mercantile marine the flag is rectangular. When Norway separated from Denmark in 1814, the first flag was red with a white cross on it, and the arms of Norway in the upper corner of the hoist, but as this was found to resemble too closely the Danish flag, a blue cross with a white border was substituted for the white cross. This, it will be seen, is the Danish flag with a blue cross imposed upon the white one. For a man-of war the flag is precisely similar to that of Sweden in shape; i.e., converted from the rectangular into the three-pointed design. While Sweden and Norway remained united the flag of each remained distinct, but each bore in the top canton of the hoist a union device, being the combination of the Norwegian and Swedish national colours and crosses. In each of the three above national ities the flag used for a royal standard is the man-of-war flag with the royal arms imposed on the centre of the cross.

The Belgian tricolour is vertical, the stripes being black next the hoist, yellow in the centre and red in the fly. That of the Netherlands is a horizontal tricolour, red above, white in the centre and blue below. In both countries the same flag is com mon to both navy and mercantile marine, but when the flag is used as a royal standard the royal arms are displayed in the central stripe. The black, yellow and red of the Belgian flag are the colours of the duchy of Brabant, and were adopted in 1831 when the monarchy was founded. The original Dutch colours adopted when Holland declared its independence were orange, white and blue, the colours of the house of Orange, and when and how the orange became red is not quite clear, though it was certainly prior to The blue and white which form the colouring of the Greek flag shown in our illustration were adopted by the National As sembly at Epidaurus on Jan. 7, 18 2 2. They also happen to be the colours of the house of Bavaria, a member of which, Prince Otho, was elected to the throne of Greece in 1832. The stripes are nine in number—five blue and four white—with, in the upper corner of the hoist, a canton bearing a white cross on a blue ground.

The very simple flag of Switzerland is one of great antiquity, for it was the emblem of the nation as far back as 1339, and probably considerably earlier. In addition to the national flag of the Swiss confederation, each canton has its own cantonal colours. In each case the flag has its stripes disposed horizontally. Basel, for in stance, is half black, half white; Berne, half black, half red; Glarus, red, black and white.

The Turkish crescent moon and star were the device adopted by Mohammed II. when he captured Constantinople in Originally they were the symbol of Diana, the patroness of Byzan tium, and were adopted by the Ottomans as a triumph, for they had always been the special emblem of Constantinople, and even now in Moscow and elsewhere the crescent emblem and the cross may be seen combined in Russian churches, the crescent badge, of course, indicating the Byzantine origin of the Russian church. The symbol originated at the time of the siege of Constantinople by Philip the father of Alexander the Great, when a night attempt of the besiegers to undermine the walls was betrayed by the light of a crescent moon, and in acknowledgment of their escape the Byzantines raised a statue to Diana, and made her badge the symbol of the city. Both the man-of-war and mercantile marine flags are the same, but the imperial standard of the sultan was scarlet, and bore in its centre the device of the reigning sovereign. This device was known as the "Tughra," and consisted of the name of the sultan, the title of khan, and the epithet al-Muza ff ar Daima, which means "the ever victorious." The origin of the "Tughra" was that the sultan Murad I., who was not of scholarly parts, signed a treaty by wetting his open hand with ink, and pressing it on the paper, the first, second and third fingers making smears close together, the thumb and fourth finger leaving marks apart. Within the marks thus made the scribes wrote in the name of Murad, his title, and the epithet above quoted. The "Tughra" dated from the latter part of the 14th century.

The imperial flag of Persia is a horizontal tricolour of green, white and red, with the lion and sun on the white ground. The merchant flag is somewhat similar, but omits the lion and sun device.

The national flag of Siam has five horizontal stripes of red, white, blue, white and red. The naval flag is similar but has the addition of a red ball in the middle within which is a white ele phant. That of Korea, a white flag with, in the centre, a ball, half red, half blue, the colours being curiously intermixed, the whole being precisely as if two large commas of equal size, one red and the other blue, were united to form a complete circle.

The Chinese republic flies a flag of red with a blue field in the upper hoist bearing a white ball surrounded by 16 triangular rays.

Among the South American republics the Brazilian flag is pecu liar inasmuch as it is the only national flag which carries a motto.

Mexico flies precisely the same tricolour as Italy, but plain in the case of the merchant ensign, and charged on the central stripe with the Mexican arms when flown as a man-of-war ensign.

The Argentine flag is flown by the navy, but, when used by the mercantile marine, the sun emblazoned on the central white stripe is omitted, the flag otherwise being precisely the same.

The Venezuelan flag of the navy is also the flag of the mercantile marine, but the shield bearing the arms of the State is not in troduced into the yellow top stripe in the corner near the hoist, as in the naval flag.

The Chilean eiisign is used alike by men-of-war and vessels in the mercantile marine, but, when flown as the standard of the president, the Chilean arms and supporters are placed in the centre of the flag.

The flag of the mercantile marine of Peru is plain red, white, red in vertical stripes, and becomes the naval ensign when charged on the central stripe with the Peruvian arms as shown in our illustration. In fact, in nearly every case with the South American republics, the ordinary mercantile marine flag becomes that of the war navy by the addition of the national arms, and in some cases is used in the same way as a presidential flag.

In nearly every case the flags of the lesser American republics are tricolours, and in a very great many of them the flags are by no means such combinations as would meet with the approval of European heralds. All flag devising should be in accordance with heraldic laws, and one of the most important of these is that colour should not be placed on colour, nor metal on metal, yellow in blazonry being the equivalent of gold and white of silver. Hence, properly devised tricolours are such as, for example, those of France, where the red and blue are divided by white, or Belgium, where the black and red are divided by yellow. On the other hand, the yellow, blue, red of Venezuela is heraldically an abom ination.

Manufacture and Miscellaneous Uses.

Flags, the manu facture of which is quite a large industry, are almost invariably made from bunting, a very light, tough and durable woollen ma terial. The regulation bunting used in the British navy is in gin. widths, and the flag classes in size according to the number of breadths of bunting of which it is composed. The great centre of the manufacture of flags, as far as the British navy is con cerned, is the dockyard at Chatham. Ensigns and Jacks are made in different sizes; the largest ensign made is 33f t. long by z 64f t. in width ; the largest Jack issued is 24f t. long and i 2f t. wide.The dimensions of a flag should be either square or in the pro portion of two to one, and it is this latter dimension that is used in the British navy and generally.

Signalling flags are dealt with elsewhere (see SIGNAL), and here it will only be necessary to make brief allusion to some inter national customs with regard to the use of flags to indicate cer tain purposes. For long a blood-red flag has always been used as a symbol of mutiny or of revolution. The black flag was in days gone by the symbol of the pirate; to-day, in the only case in which it survives, it is flown after an execution to indicate that the requirements of the law have been duly carried out. All over the world a yellow flag is the signal of infectious illness. A ship hoists it to denote that there are some on board suffering from yellow fever, cholera or some such infectious malady, and it re mains hoisted until she has received quarantine. This flag is also hoisted on quarantine stations. The white flag is universally used as a flag of truce.

At sea striking of the flag denotes surrender. When the flag of one country is placed over that of another the victory of the former is denoted, hence in time of peace it would be an insult to hoist the flag of one friendly nation above that of another. If such were done by mistake, say in "dressing ship" for instance, an apology would have to be made. This custom of hoisting the flag of the vanquished beneath that of the victor is of com paratively modern date, as up to about a century ago the sign of victory was to trail the enemy's flag over the taffrail in the water.

Each national flag must be flown from its own flagstaff, and this is often seen when the allied forces of two or more powers are in joint occupation of a town or territory. To denote honour and respect a flag is "dipped." Ships at sea salute each other by "dipping" the flag, i.e., by running it slowly down from the masthead, and then smartly replacing it. When troops parade before the sovereign the regimental flags are lowered as they sa lute him. A flag flying half-mast high is the universal symbol of mourning. When a ship has to make the signal of distress, this is done by hoisting the national ensign reversed, i.e., upside down. If it is wished to accentuate the imminence of the danger it is done by making the flag into a "weft," i.e., by knotting it in the mid dle. This means of showing distress at sea is of very ancient usage, for in naval works written as far back as the reign of James I. we find the "weft" mentioned as a method used by ships for showing distress.

We have already alluded to the Union Jack as used for denoting nationality, and as a flag of command, but it also serves many other purposes. For instance, if a court-martial is being held on board any ship the Union Jack is displayed while the court is sitting, its hoisting being accompanied by the firing of a gun. In a fleet in company the ship that has the guard for the day flies it. With a white border it forms the signal for a pilot, and in this case is known as a Pilot Jack. In all combinations of signalling flags which denote a ship's name the Union Jack forms a unit. Lastly, it figures as the pall of every sailor or soldier of the empire who receives naval or military honours at his funeral.