Nitrogenous Fertilizers

NITROGENOUS FERTILIZERS In natural conditions a nitrate, probably calcium nitrate, is the source from which plants derive their nitrogen, but the changes in the soil are such that sodium or potassium nitrates are equally serviceable. Further, ammonia is rapidly oxidized to nitrate in the soil; hence ammonium salts, or any other compounds rapidly converted into ammonia, also supply nitrogen for plants. So far as is known, the ammonia is not generally assimilated direct, al though some plants can do this : certain micro-organisms in the soil are so active, however, that the ammonia is converted into nitrate before the plant takes it up. The nitrogenous fertilizers are: Nitrates: sodium (the most used) ; calcium (increasingly used) ; potassium (used only in horticulture) .

Ammonium salts: sulphate (the most usual) ; phosphate (coming into use) ; chloride (valuable for certain crops) .

Substances easily converted into ammonia: Calcium cyanamide (most used) ; urea (coming into use) .

Effects of Nitrogenous Fertilizers.

Nitrogen starvation is characterized by stunted growth and sickly yellow colour of the leaf, the yellowing and dying being general all over the leaf, as distinct from the effect of potash starvation where the dying is from the tip and edges inwards. Addition of nitrate causes rapid improvement in its colour and growth. F. G. Gregory, working with barley, has shown that only the leaf area increases and not the assimilation rate, in contradistinction with phosphate and po tassium, both of which increase the efficiency as well as the leaf area.Greater quantities of nitrate lead to the development of large dark green leaves which are often crinkled, soft, sappy, and liable to insect and fungus pests, possibly because of the thinning of the walls or changes in tissues or in composition of the sap. C. R. Hursch shows that the amount of sclerenchyma is reduced in proportion to the collenchyma in the wheat plant, thus favouring the attack of Puccinia graminis, the mycelium of which can de velop only in the collenchyma. . • A further effect of a large supply of nitrogen relative to other nutrients is a retardation of ripening. Seed crops like barley that are cut dead ripe are not supplied with much nitrate, but oats, which are cut before being quite ripe, can receive larger quanti ties. All cereal crops, however, produce too much straw if the nitrate supply is excessive, and the straw does not commonly stand up well, but is beaten down or "lodged" by wind and rain. Swede and potato crops also produce more leaf, but not propor tionately more root or tuber, as the nitrogen supply increases; no doubt the increased root would follow, but the whole process is sooner or later stopped by the advancing season—the increased root does, in fact, follow in the case of the later-growing man gold. Tomatoes, again, produce too much leaf and too little fruit if they receive excess of nitrate. On the other hand, crops grown solely for the sake of their leaves are wholly improved by in creased nitrate supply : growers of cabbages have learned that they can not only improve the size of their crops by judicious applica tions of nitrates, but they can also impart the tenderness and bright green colour desired by purchasers.

Sources.

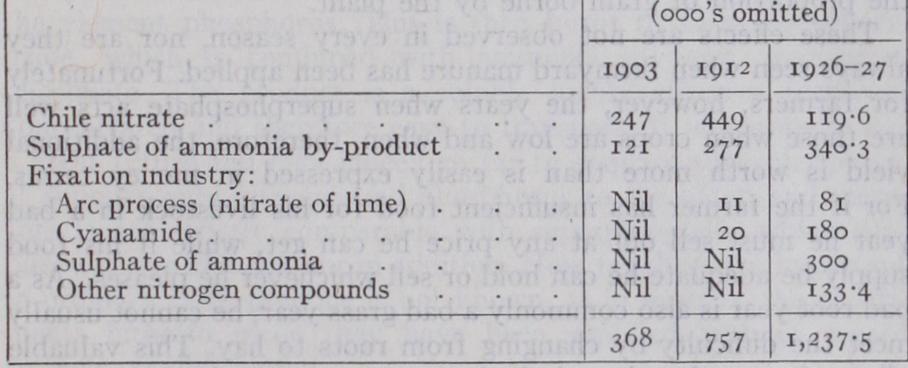

Prior to the World War, Chile was the main source of nitrate of soda, and coal of sulphate of ammonia. These were the two chief nitrogenous fertilizers. Synthetic fertilizers were obtainable, the industry having been founded as a result of Sir William Crookes's impressive address at the British Association in 1898, but they played only an insignificant part in farm prac tice. During the war, extensive factories for the preparation of ammonia or nitrate from atmospheric nitrogen were erected in Central Europe, and since the war in other countries also.Three processes are used in the fixation of atmospheric nitrogen (q.v.). The arc process, yielding calcium nitrate, is almost limited to Norway, where water-power is abundant ; the cyanamide pro cess, used in Switzerland and other countries possessing water power or coal; and a catalytic process, now becoming the most popular, usually a modification of the Haber process, which yields ammonia convertible into any of four compounds : the chloride by combining the process with the manufacture of soda; the sul phate by reaction with gypsum; nitric acid by oxidation; or urea by other processes. The net result of all these activities is to give the farmer two new nitrogenous fertilizers which he never had before the war, namely ammonium chloride and urea, and to in crease enormously the total amount of fertilizers obtainable. Some idea of the position now, as compared with pre-war days, can be gathered from the following table of the world's output in the years 1903, 1912 and 1926-7.

World's Production of Nitrogen Compounds in Thousands of Metric Tons (2,000 lb.) of Pure Nitrogen Further large increases in production are foreshadowed both in Germany and in Britain : in Germany the Stickstoff Syndikat, and in Britain, Nitram Ltd., controls the situation. The British works are at Billingham, near Stockton-on-Tees, owned by Syn thetic Ammonia and Nitrates Ltd., a part of Imperial Chemical Industries Ltd., and are expanding rapidly.

Sodium Nitrate,

usually called nitrate of soda, comes wholly from the rainless regions of Tarapaca and Antofagasta in the north of Chile, where it forms deposits near the surface of the soil. The deposits occur in detached areas stretching over a wide range ; in spite of the large annual consumption there still re mains a vast supply for the future. The crude nitrate is excavated by a process of trenching; it is then crushed, purified by recrystal lization and put up in bags for the market. Recently, improved methods for extraction have been introduced, such as those of Gibbs, Butler, etc., in place of the older Shank's system still in use among many of the companies.Nitrate of soda is very quick acting as a fertilizer and can be taken up immediately by the plant. It finds application in two cases : (1) in case of emergency, when young plants are suffering through the attack of a pest, or in cold weather; (2) in ordinary practice as a top dressing for the crop. ,It causes increases of prac tically all crops grown in Great Britain; the dressing applied varies from 1 cwt. per acre, suitable for wheat in spring or grass laid for hay, to io cwt. per acre used on the valuable early cabbage and broccoli crops in Cornwall.

Nitrate of soda readily washes out of the soil and must there fore not be applied until it is needed.

Nitrate of Lime.

This is made both in Norway and in Ger many. The production in recent years averages i6o,000 tons per annum, practically all of which is taken in Europe, consumption outside being negligible. It is used on wheat, oats, hay, barley, forage crops, sugar beet, cabbage and mangolds. The problem of transport and storage was at one time a difficulty but is now largely overcome. In north Europe, Scotland, and the northern counties of England special bags are used; but in the warmer and moister midland and southern counties barrels are better.The older Norwegian nitrate of lime contained 13% of nitro gen; modern German material contains 15.5%; there is an Eng lish product, called "Nitrochalk," one grade of which contains io%, the other Sulphate of Ammonia.—Until recently this was made wholly from coal. This still remains an important source, but the syn thetical processes now produce nearly as much, and will soon produce more. Until recently sulphate of ammonia has always contained free acid; not more than about 0.05%, insufficient to affect the soil though sometimes enough to rot the bags, make the sample rather sticky and prevent it drilling easily. The method of preparation has now been improved so that it turns out a "neutral" sulphate containing less than 0.02% of acid which can be dried better and therefore is slightly more concentrated than the old substance : it contains 21.1% of nitrogen or 251% am monia against 20.8% nitrogen or 25+% ammonia. The chemical is very easy to drill, can be stored easily and is entirely free from stickiness. For home use it is excellent. In the export trade it has shown an unexpected tendency to cake, a disadvantage that can now apparently be overcome. Great Britain is the chief exporting country and the United States comes second; Spain, Japan, Java and France are the chief importing countries.

Sulphate of ammonia is used on all crops in Britain, particularly potatoes, for sugar beet and other crops in France, oranges in Spain, rice in Japan and sugar in Java. There is evidence that it could advantageously be used for cotton. The greatly increased output tends to force down its price and so to widen its range of effective use. Attempts are being made to extend its use on grass land by extensive manuring and close grazing, but the tests have not continued long enough to show whether the method is a financial success.

Sulphate of ammonia differs in two important respects from nitrate of soda. When applied to the soil it reacts with calcium carbonate, giving rise to calcium sulphate and ammonium carbo nate. The calcium sulphate washes out in the drainage-water, but the ammonia does not, but becomes absorbed by some of the reactive constituents contained in the soil. The ammonia becomes nitrified by bacterial action, and presumably is changed to calcium nitrate through interaction with more calcium carbonate. The calcium nitrate, however, is not wholly retained by the plant; the calcium is left in the soil and reconverted into carbonate.

There still remains a loss of loo lb. of calcium carbonate for each 132 lb. of ammonium sulphate applied, and on soils deficient in lime this becomes serious for two reasons: the lime is greatly needed for other purposes; and in its absence ammonium sulphate leaves an acid residue in the soil, the ammonium portion being more completely taken by plants than the rest. Now most agri cultural plants will not tolerate this acidity, and in extreme cases completely refuse to grow. This remarkable action was first served in 1890 by Dr. Wheeler at the Rhode Island experiment station, where it has been more fully studied than anywhere else. A few years later it was seen at the Woburn experimental farm and described by Dr. Voelcker.

Dressings of lime must therefore be given periodically to avoid this trouble.

The absorption of ammonia. by the soil is an advantage in regions of torrential rainfall. Where nitrate of soda might be completely washed away sulphate of ammonia remains safely in the soil.

Urea.

This substance is now prepared synthetically and it promises to be a highly important fertilizer. It contains 47% of nitrogen, and is thus more than 21 times as concentrated as sulphate of ammonia and 3 times as concentrated as nitrate of soda, a great advantage for transport and cartage. In the soil it is rapidly converted into ammonium carbonate which is then oxidized to nitrate. It does not appear to give its best results when used as a top dressing, and is better put into the soil at the same time as the seed, and speedily covered up. It seems to be safe for all crops, and does not make the soil acid, nor does it cause poaching of heavy soils ; indeed, it appears to be remark ably free from the indirect action on soil other fertilizers show.

Calcium Cyanamide

.—This is prepared by heating a mixture of calcium oxide and carbon to a high temperature in an electric furnace : the resulting calcium carbide is then heated in a stream of nitrogen. Great quantities are made in Sweden, Switzerland and Italy where cheap water power is available ; there are also factories in Japan and elsewhere. Recently there have been important changes in the method of manufacture, and the modern product contains 19% of nitrogen and 6o% of total lime, of which 22% is free and 38% is in combination as cyana mide. Practically all the nitrogen is in the cyanamide form.In the soil it changes to urea, by a reaction not yet understood but apparently not brought about by micro-organisms : the urea then decomposes as described above. In some conditions, e.g., in presence of an alkali, cyanamide polymerizes, two molecules join ing together to form one of the dicyanodiamide, a substance which in any large quantity is poisonous to plants and also to the nitrifying bacteria, and in any case has nothing like the fertilizing value of cyanamide. The older samples were dusty and unpleasant to handle, but this difficulty is now overcome.

Cyanamide has a retarding effect on germination of rapidly germinating seeds if it is applied along with them but not if it is applied to the land a few days beforehand: this is, therefore, always recommended. It has the advantages of cheapness, of sup plying calcium, and apparently, though this is not yet fully demonstrated, of producing grain in cereals without lengthening the straw so much as sulphate of ammonia would do. Its effects are being studied at Rothamsted and elsewhere.