Organic Manures

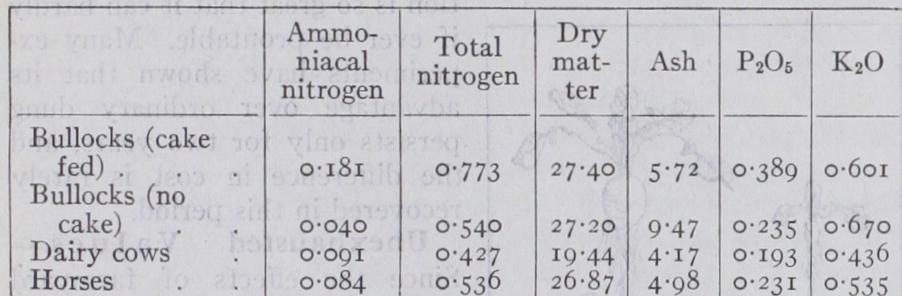

ORGANIC MANURES The older kinds of manure, which are still the most important on the farm, are of animal and vegetable origin and contain much combustible organic matter : they are therefore called "organic" to distinguish them from the inorganic salts or "artificial fer tilizers." Far the most important is farmyard manure. This consists of the solid and liquid excretions from the animals, together with the litter. The solid excretions, or faeces, contain the undigested and indigestible parts of the food, which is made up of about half of the bulky food supplied to the animal (hay, straw, etc.) and a small part of the concentrated food (corn, cake, etc.). This material has resisted the attack of the digestive fluids in the ani mal and it also proves somewhat resistant to the decomposition agents in the soil. The liquid excretion, or urine, contains most of the nitrogen and potassium of the digested portion of the food which, after entering the circulation and being used by the animal, is excreted in a soluble form very useful for plant growth. The richest manure is therefore that which contains the most and richest urine, given by animals fed on much easily digestible food rich in protein, such as feeding cakes, meals, etc. But the richness of the urine also depends on the animal. Fatting animals keep back very little of their nitrogen—only about 5%—and pass most of it out in the urine. Growing animals and milch cows keep back considerably more, so that the urine is correspondingly poorer; consequently fatting animals make better manure than young stock or dairy cows. The litter plays a very important part : it absorbs the urine, and on decomposition it adds valuable fer tilizing material to the manure. Straw, peat, moss and bracken are all used ; of these straw is much the commonest and contains fair amounts of nitrogen and potassium, has considerable power of absorbing urine, and encourages a biological fixation of ammonia.

The composition of farmyard manure is in principle readily ascertained. Knowing the weight and composition of the food and litter, and deducting the food constituents retained by the animal, it is easy to calculate the amount of fertilizing materials in any particular lot of farmyard manure. Experiments by J. A. Voelcker, T. B. Wood and E. J. Russell show that the calculation does not come out right, the quantity of nitrogen found in the manure being usually about i 5% less than was anticipated. The loss does not take place in the animal: physiological experiments have shown that the whole of the nitrogen of the food is excreted in the urine and faeces : the loss goes on through volatilization and the action of micro-organisms while the manure is in the stall and before it is removed. After making the allowance the total Magnesium, present in German kainit and potash manure salts, but not in those from Alsace, is of advantage in some con ditions not well known, so that its effects cannot be predicted. It has, however, proved beneficial on potatoes and sugar beet, and Garner has shown that tobacco plants suffering from shortage of magnesium become liable to a peculiar chlorosis known as "sand drown." quantity of fertilizing material in the heap can be accounted for. The amount per ton, however, depends on the amount of water present and this varies with the different animals; sheep and horses giving more concentrated urine and faeces than cattle and pigs.

In practice, however, farmyard manure is rarely used im mediately it is made : it has generally to be kept as a matter of convenience and it then undergoes two types of changes, mechani cal or physiological losses through leaching and volatilization, and chemical changes resulting from the activities of the hosts of micro-organisms, including bacteria arid fungi, that flourish in it. The decomposition brought about by these organisms is in large part an oxidation and it liberates much heat. Relatively dry manure, e.g. horse dung, rises considerably in temperature; wet ter manure, like cow dung, does not because of the great amount of heat needed to warm up all the water present and because much water means little air. This production of heat involves the corn bustion of material in the heap so that there is a corresponding loss of dry matter. The loss of nitrogen may be considerable. At the high temperature—sometimes as high as 7o° C—many of the micro-organisms cannot function and may be killed. H. Rege has shown, however, that some of the fungi present remain active at 50° C and upwards (Annals Applied Biology, 1927, vol. xiv., The changes fall into two groups. The cellulose is decomposed by some of the organisms, notably certain fungi, and forms humus, a black sticky substance of great value in soil fertility because of its useful effects on the physical properties: tilth, and the power of holding moisture. To effect this decomposition of cellulose the organisms require a supply of easily available nitrogen, i.e., ammonia and amides, and therefore the process goes best when the animals have received cake and meal and the urine is all saved in the heap. The nitrogen taken by the organisms is converted into their cell substances ; this causes a loss of soluble but a gain of insoluble nitrogen.

The nitrogen compounds of the manure undergo opposite kinds of changes. (I) If much nitrogen is present ammonia is formed, some of which is lost by volatilization and some is assimilated by the micro-organisms as stated above. (2) If but little nitrogen is present the preceding changes are reduced to a minimum and there is a tendency for nitrogen to be assimilated from the air by certain bacteria. (3) Complex insoluble nitrogen compounds in the manure tend to break down to ammonia. (4) Ammonia tends to be assimilated by the organisms decomposing the cellulose, and converted by them into complex insoluble compounds.

In consequence of these various changes farmyard manure, whatever its original content of nitrogen compounds, tends to be come more uniform in composition on storage.

These changes take place whether the manure is stored in heaps or is ploughed into the soil. They are greatest in heaps to which air is admitted : they are least when air is excluded. The losses vary in the same way. They are least when air is excluded and the heap sheltered from the rain, in a compact heap stored under cover, or, what comes to the same thing, in manure made and kept under the animal. They become greatest, amounting to 40% or more, when the manure is made in open yards and then loosely packed into heaps and exposed to rain in the open. Some amount of change is unavoidable, and the rise of temperature has the great and increasing value that it kills weed seeds always present in the manure. But it is desirable to minimize the losses and in order to do this the following general rules should be observed.

Manure Made from Fatting Beasts.

If this is made in covered yards it should be left under the beasts until it is wanted. Defective roofing and spouting should be made good so far as possible to avoid washing by rain. If made in open yards the manure as soon as convenient should be hauled out and lightly clamped.The clamp should be so placed that it is not unduly exposed to rain; shelter should if possible be provided in the form of a layer of earth, thatched hurdles, corrugated iron sheets, etc. If any black liquid is running away it is a sign that shelter is insufficient and that wastage is going on. It is not sufficient to collect the liquid, though this should be done ; steps should be taken to pro vide more shelter also. The clamp should not be disturbed until it is wanted.

Manure Made from Dairy Cattle.

This has usually to be thrown out daily. It should be well protected from rain. The worst plan is that seen in some of the northern dales of England, where the manure is thrown out of a hole in the wall and lef t exposed to weather, with the result that streams of black liquid flow away. A much better plan is to cart the manure to a dung stead as is done in other parts of the country.

Liquid Manure.

Special care should be taken of the liquid manure draining from the cowsheds. This should be run into a tank and applied when convenient to the land. It may go on to grass land at almost any time, and to arable land after the autumn and before the middle or end of May. It is specially rich in nitrogen and potassium.Time of Applying Farmyard Manure to the Land.—On heavy soils it is best to plough in the manure in autumn, winter or early spring in the "long" or fresh condition. The undecom posed straw helps to keep the soil open, it facilitates drainage and the action of winter frost. Losses of nitrogen compounds are reduced to a minimum : any decomposition of cellulose or other non-nitrogenous compounds is an advantage since it leads to assimulation of soluble nitrogen compounds which would other wise be lost during the winter.

On light soils the "long" manure should not as a rule be ploughed in later than winter or it may bring about too much evaporation of water : the manure should be left to decompose in the heap before it is applied to the land. In districts of high rainfall this objection disappears, and spring applications of manure (provided it has been well stored) gives better results than winter appli cations.

Value of Cake Feeding.

From the foregoing it is clear that the feeding of cake to the animals enhances the value of the manure by enriching it in soluble and therefore available nitrogen compounds and by facilitating the conversion of the straw into highly valuable humus. "Cake-fed dung," to use the farmers' expression, is therefore of great value and is much prized on the farm. Unfortunately under present conditions its cost of produc tion is so great that it can hardly if ever be profitable. Many ex periments have shown that its advantage over ordinary dung persists only for two years, and the difference in cost is rarely recovered in this period.Unexhausted V a l u es.— Since the effects of farmyard manure are not exhausted in one year, but persist over several, the custom has grown up in Brit ain, and is now enforced by law, of giving compensation to far mers quitting their holdings for manure they have applied to the land. The first tables for the guidance of valuers were drawn up by Lawes and Gilbert in 187o ; they have been periodi cally revised and were reissued in 1914 by J. A. Voelcker and A. D. Hall, who recommend that compensation should be payable in respect of half the nitrogen and three-quarters of potash and phosphoric acid contained in the food, it being supposed that the remainder is lost. (Journal Royal Agricultural Society, I 914, lxxiv, I 04. ) Farmyard Compared with Artificial Manures.—When artificial fertilizers were first introduced, chemists felt much justi fiable pride in their discovery. In Lawes's and Gilbert's first ex periments the complete artificial manures had actually given larger yields of wheat and barley than had farmyard manure and although Lawes and Gilbert themselves did not urge that artificials were better than farmyard manure, some of their successors did so. The great French agricultural chemist, Georges Ville, went so far as to assert that farmyard manure was unnecessary and could in practice be economically replaced by artificial manures.

Practical men in Great Britain never accepted this view but maintained that farmyard manure was more effective than arti ficial fertilizers and came in for some abuse for their supposed prejudice against new ideas and scientific discoveries. As time went on, however, it appeared that the superiority of artificial to farmyard manure was not permanent. For the first few years the artificials considerably enhanced the fertility of the soil, but after a time their effect began to fall off. Farmyard manure, on the other hand, shows no such falling off and is more effective in permanently maintaining fertility. Crops receiving it are less liable to suffer from seasonal factors than those receiving artificials only, so that the fluctuations in yield from season to season are less marked on the farmyard manured plot. Again some crops seem to respond markedly to farmyard manure. Clover, one of the most important crops in Great Britain, is an example : it responds better to farmyard manure than to any combination of artificials yet tested, giving not only a better yield of clover hay but also enriching the ground and so improving the succeeding crop. Gooseberries were shown by Spencer Pickering at the Woburn fruit farm to respond better to farmyard manure than to artificials and a similar result is shown by citric fruits at Riverside, California. These and other experiments prove that farmyard manure has important effects on plant growth which are not produced by artificial manures.

The effects are something more than nutrition with nitrogen, potassium and phosphate : at Askov in South Jutland a comparison between farmyard manure and artificial fertilizers containing the same amount of plant nutrients has shown that the nutrients in the farmyard manure have only about half the value of those in the artificial fertilizers. The composition of farmyard manure is as under :— Sewage Sludge.—Unfortunately no practicable means of real izing the value of sewage has yet been devised. Broad irrigation and sewage farming answer under certain conditions, but not as general methods of treatment. The only material generally avail able is the sludge which is prepared by some precipitating or settling process, and it contains therefore only the insoluble corn pounds and not the soluble and valuable nitrates, ammonia, etc. It is usual to add a certain proportion of lime and then to force the mass into presses, when it forms a cake containing roughly 50% of water, 15 to 25% of organic matter and 25 to 35% of mineral matter much of which is lime, and about 1% each of nitrogen and of This is not usually of much fertilizing value. At some places other wastes and residues are added to enrich the sludge and in some northern towns a process is at work to extract the fat, grease, etc., which in modern times have become too precious to lose even in sewage : the resulting products con tain respectively 2 and 34% of nitrogen and are of distinct ferti lizer value. The best of these materials is the so-called activated sludge prepared by blowing air through the sewage; this has a very different character from the older types and contains as much as 5% or more of nitrogen and over 4% of it is a promising fertilizer.

Other Organic Manures.

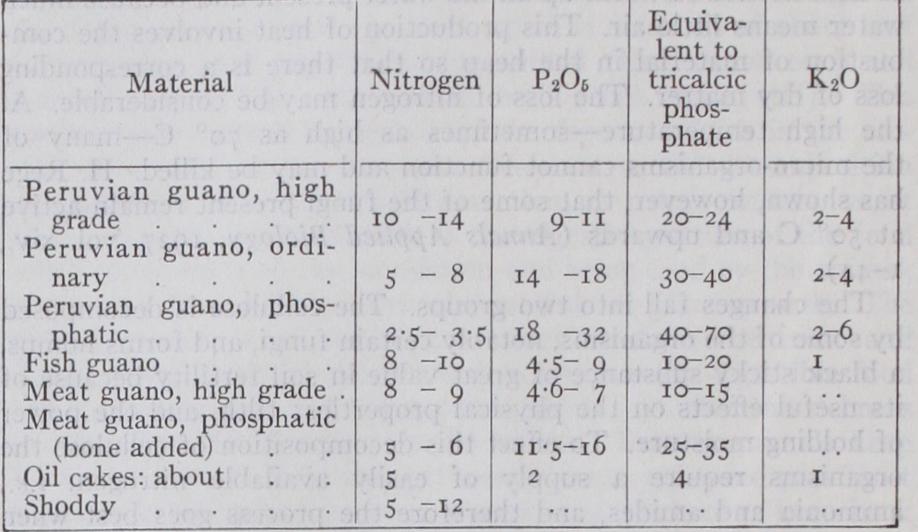

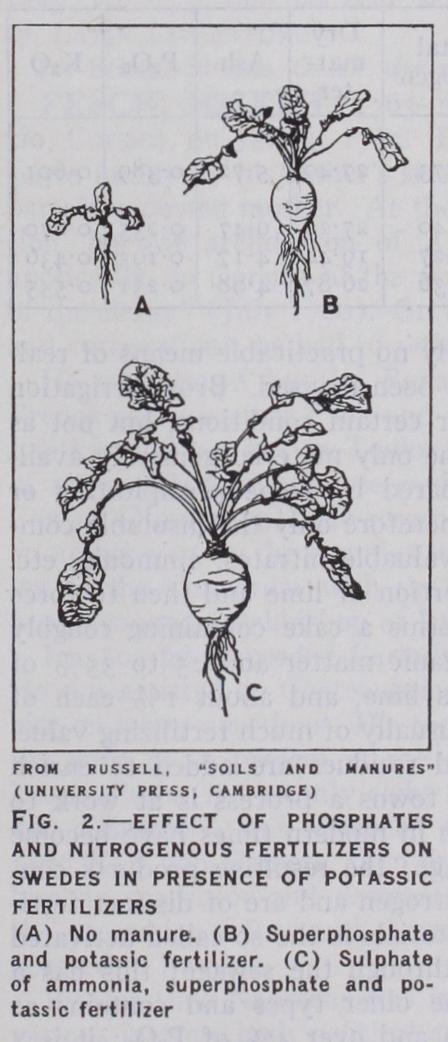

Broadly speaking any animal or vegetable material can be used as manure, and if it can be made to contain more than 5% of nitrogen it may become an article of commerce : poorer materials rarely pay for transport. The guanos are the droppings of sea birds, feathers, etc., gathered from small islands off Peru, South Africa, and elsewhere. Fish and meat guanos are prepared from fish and meat unsalable as human or animal food, the fat having been wholly or partly removed, Various seed meals (rape, etc.) are residues left after extraction of oil and for some reason unsuited for animal food. Shoddy is a waste material from the Yorkshire mills which tear up old cloth and woollen rags to make them into new cloth. All these have fertilizer value though they are more appropriate for special purposes than for ordinary farming. Their composition varies, but the following are typical figures :—