Rugby Football

FOOTBALL, RUGBY. From the first there were two dis tinct camps among football players—those who preferred to use only their feet, and those who used both hands and feet—and, for some reason which no one seems to know, the Rugby school game gained more adherents than any other among those who favoured the handling of the ball. A Rugby boy named William Webb Ellis is said to have been the first player to catch the ball and run with it, thus originating the distinctive feature of the Rugby game. This was in 1823; but it was not until the '6os that the game began to be taken seriously by clubs. Two of the first to do so were Blackheath, in 1862, and Richmond, in 1863. In the next few years many more new clubs sprang into existence, including the Oxford university club, in 186q, and the Cambridge university club, in 1872, in which year matches between the two universities were begun. In Jan. 1871, 17 clubs and three schools met and formed a governing body under the title of the Rugby Union. From this time the two games of Rugby and Association foot ball went their separate ways, and were rendered the more dis tinctive by the fact that the Rugby players used an oval ball and the Association players a round one.

The Early Scrummages.

In both character and methods the Rugby game has changed more completely from its original form than any other game. In its earliest days the methods of play were based almost entirely on the traditions of the game at Rugby school, with its Bigside matches, in which anything from 4o to Too or more players took part. Similar matches became popular in other schools, but it was customary in ordinary matches to play 20 a side. Though the players of the time seem to have enjoyed the game immensely, it was undoubtedly a rough and tumble affair, with many features which would have prevented its development without drastic modifications. It consisted mainly of fierce scrummaging, in which the bulk of the players would be locked and wedged together, in a heaving mass, sometimes for ten minutes or more at a time, struggling and kicking for a ball which most of them could not see. Often these scrummages would be continued long after a player outside the scrummage had run off with the ball; or sometimes the ball would eventually be found lying perfectly still a yard or so away. But one great principle animated the players—that it was immaterial if, in kicking for the ball, they kicked their opponents' shins.

Hacking and Mauling.

From accidental kicking of this kind it was a natural step to intentional kicking, or hacking as it was called, and a player who could not give and take hacks was not considered worth his salt. Hacking developed into a deliberate means of forcing a way through the opposition; and kicking the shins of a player when running—known as "hacking over"—be came a recognized feature of the play. An old Rugbeian, the late A. G. Guillemard, who assisted in the foundation of the Rugby Union, related how he once saw the crack "hack" of the Woolwich Academy team, then noted for its fierce forward play, come through the scrummage and finish off his triumphal progress by kicking a half-back clean off his legs. Another curious feature of the game at that time and for many years afterwards was the maul-in-goal. This occurred when a player with the ball was tackled over the goal line. The tackler and the tackled player would then engage in a sort of private Wrestling match for possession of the ball, while the rest of the players in both teams became merely interested spectators. It was not uncommon to see the two men lying on the ground, locked in deadly grips, motionless sometimes for several minutes until one of them gave a sudden heave, which might only alter their positions a little. On the initiative of the Richmond -club, most other clubs in the London area abandoned hacking by mutual consent after 1866, and when the Rugby Union drew up its first laws in 1871, the practice was made illegal.

Fifteen a Side.

The new laws did much towards improving the general tone of the game, but the dawn of the modern game really broke with the general reduction in the number of players from 20 a side to 15 a side. The universities first adopted the change in 1875, and in the following year it was introduced into international matches. From that time the game became more and more open and interesting in character, players began to realize the value of team work, and new methods developed rapidly. Instead of pushing blindly in the scrummages, stand ing upright to form the tighter mass, forwards began to push with their heads down so that they could see the ball, and to develop skill in controlling it and breaking away with it. For wards were no longer chosen entirely for their weight and strength, but also for their ability to dribble the ball and to com bine in concerted tactics.

Wheeling and Heeling Out.

Of these tactics wheeling or screwing the scrummage, so as the better to start a concerted rush, became a prominent feature. Some of the old players were frankly disgusted at this manoeuvre. For instance, Mr. Arthur Budd, a great forward of his day, wrote contemptuously of "a forest of legs scraping for possession of the ball," and char acterized the proceeding as "extremely unfair." Nevertheless wheeling became recognized as a skilful and effective part of the game, and there was no more thrilling sight than a pack of well-trained forwards wheeling the scrummage and breaking away with the ball in a rush. Dribbling developed into a high art, and it was wonderful to see men like the brothers E. T. and C. Gurdon, of the Richmond club, two of the greatest forwards of their day, break away with the ball at their feet and steer it past opponent after opponent.When the practice of heeling the ball out of the scrummage to the backs first appeared, it met with just as severe condemna tion from old players as wheeling had done. Mr. Budd referred to it as a "canker-worm of work," and wrote in the Rev. F. Mar shall's classical book on the game : "You can bet your bottom dollar that a team who habitually heel-out are no pushers. Their sole anxiety is to get the ball to their half-backs, and the same miserable scraping goes on as in wheeling." Mr. Budd's indigna tion may be the better understood when it is remembered that at one time it was regarded as exceedingly bad form, almost unfair in fact, to heel the ball out of a scrummage even if the players were in such a position that a certain score would have resulted from it. But other times, other manners. To-day Mr. Budd's "miserable scraping" for the ball is recognized as a highly specialized job, known as hooking and a clever hooker is in valuable.

Developments in Back Play.

New forward tactics brought with them new methods among the backs. Hitherto their func tions had been chiefly those of defence, and for many years it was customary to play two half-backs behind the scrummage, one three-quarter behind them, and two or three full-backs. To pass the ball was practically unknown, and regarded as a sign of "funk" in any player who attempted to do so. When one of the backs happened to secure the ball he either kicked it or tucked it under his arm and ran and dodged until he was brought down and forcibly compelled to part with it. With the development of more open play by the forwards, the backs found themselves with more work to do and fewer opportunities for individual efforts. The activities of the half-backs in particular became more and more hampered by the opposing forwards, and the position of three-quarter-back became of increasing importance. It was soon found an advantage to play two three-quarters instead of one, and one of the full-backs was accordingly transferred to that position.

The Inception of Passing.

Although the backs handled the ball more than the forwards, it was, curiously enough, among the forwards that hand to hand passing first developed to any ex tent. The Blackheath club gave special attention to short passing by the forwards and achieved such success by it that public in terest was aroused, and other players quickly followed their ex ample. But it was left to the most famous of all university captains, H. Vassall, to show the real possibilities of passing among forwards. The Vassall era at Oxford was one of the out standing periods of the game. Himself a fine forward, he trained his men not only to exploit the short passing game, but to give and take long passes, and to combine in rapid team work. The results took most of their opponents by surprise, and in four seasons, from 1881, the Oxford team suffered only two defeats— both at the hands of Edinburgh university. In the season 1882 83 the side scored 28 goals and 26 tries, and had only a goal and two tries scored against them. Apart from their success in the de velopment of new methods, the Oxford teams of that period con tained some exceptionally talented players, and among them was Alan Rotherham, who proceeded to revolutionize half-back play just as Vassall had revolutionized forward play. It is claimed that passing by the half-backs had already been started in Scotland, but Rotherham was the first to demonstrate its great possibilities. He made the half-back a connecting link between the forwards and the three-quarters, and showed the possibility of a wide variation of tactics. He demonstrated the great advantage of getting the three-quarters on the move before passing, and also of making openings for them, and it is not too much to say that on the methods he introduced, half-back play has ever since been modelled. At about the same time as Rotherham was thus gain ing fame, there appeared in the Bradford club team a player named Rawson Robertshaw, who extended Rotherham's methods still further by developing passing among the three-quarter backs. One of three brothers whose name became a household word in Yorkshire, he showed genius as a three-quarter. By that time the practice of playing three three-quarters, instead of two, had been generally adopted, and at centre three-quarter Robert shaw introduced passing to the outside men, and developed com bined work with it in a way that gave players an entirely new conception of a three-quarter line as an attacking force. It was but a short step to the introduction of another player into the three-quarter line, with the idea of making it more effective, but curiously enough it was left to Welsh clubs to demonstrate its advantages before the three-quarters were universally increased to four players. Indeed, some years elapsed before the Welsh men were able to perfect the four three-quarter game so as to show its real effectiveness. Opinion in the other countries held out against it for some time on the ground that it meant weaken ing the forwards who were thereby reduced from nine to eight players.

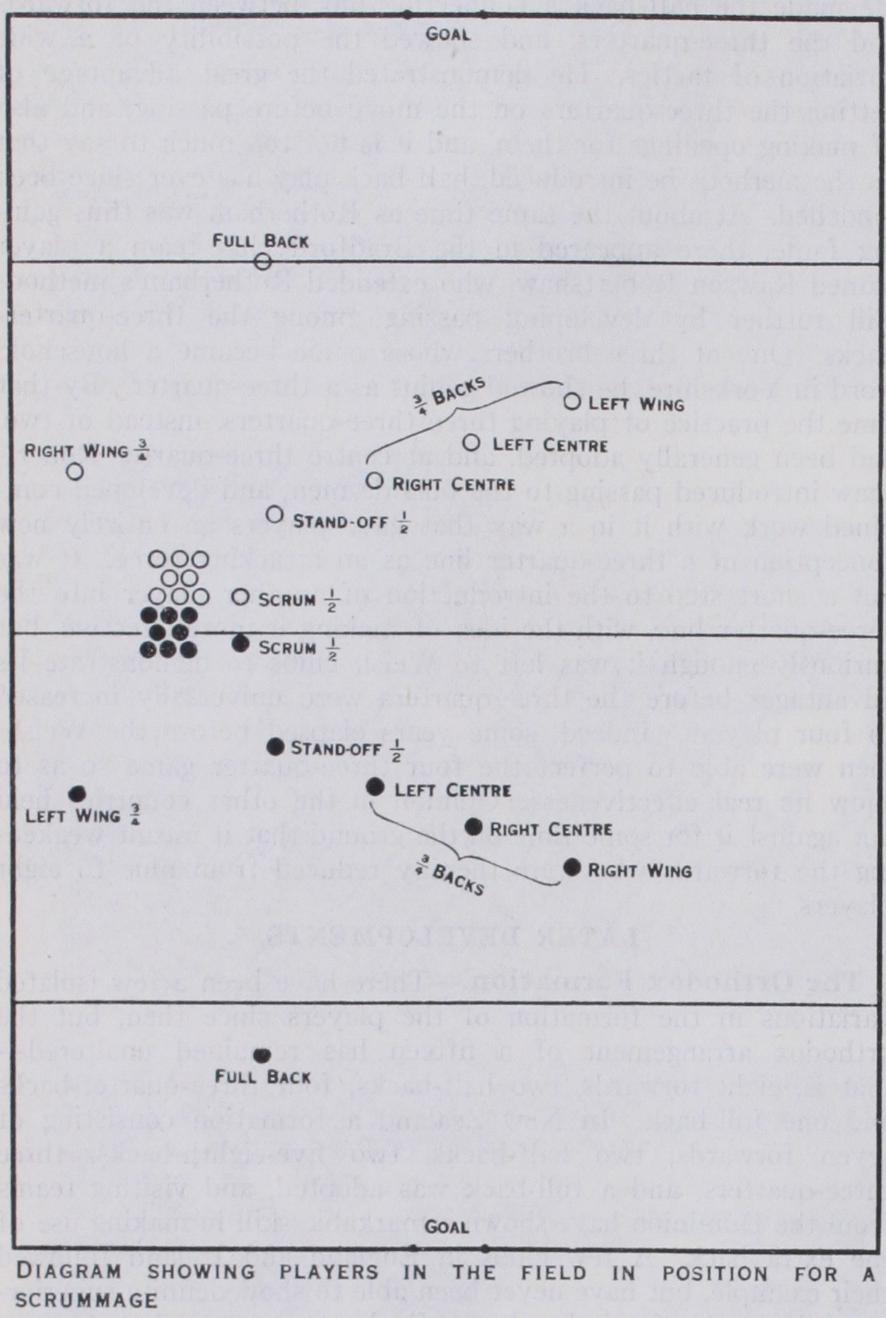

The Orthodox Formation.

There have been a few isolated variations in the formation of the players since then, but the orthodox arrangement of a fifteen has remained unaltered— that is, eight forwards, two half-backs, four three-quarter-backs and one full-back. In New Zealand a formation consisting of seven forwards, two half-backs, two five-eighth-backs, three three-quarters, and a full-back was adopted, and visiting teams from the Dominion have shown remarkable skill in making use of the extra back. A few clubs in England and Ireland followed their example, but have never been able to show definite superior ity as a result; for it has been clearly demonstrated that seven forwards must be exceptionally good to hold their own against eight ; and without that condition the extra back is generally useful only in defence. Though the scrummage is not the dom inating feature of the game that it used to be, the balance of power still remains with the forwards, and modern develop ments have chiefly centred in them. A forward is expected to be able to take his share in practically every phase of the game, and without a doubt his is the most exacting work on the field. Of real scrummaging, as it was known to the old players, there is very little to be seen ; but in their anxiety to obtain possession of the ball the forwards have had recourse to all sorts of manoeu vres of which their forbears never dreamed. The normal forma tion of the eight forwards in a scrummage is in three rows—three players in the front, two in the second row, and three at the back. The front three forwards on each side pack down shoulder against shoulder, with their heads tucked down so that they can see the ball as it is thrown between them by the scrummage half-back. The middle man in each front row is the hooker, who endeavours to sweep the ball back with his foot through the legs of those behind him. Now it is obvious that when three .men pack down in this way against another three, one of the outside men on each side will have a disengaged shoulder, and that the middle men will not be directly opposite to each other. The half-back who puts the ball in will naturally choose, if possible, to put it in on that side of the scrummage on which his own forward has the disengaged shoulder, since the middle man will then be a little nearer than his opposite number, and will thus have the first chance of hooking the ball—the outside men being debarred from doing so.

Wing Forwards.

One forward development which has had a large influence on the game all round is what is known as wing forward play. This concerns mainly the back row players in the scrummage. Briefly, it means that these players must break very quickly from the scrummage and, if their opponents get the ball, rush on the opposing backs to nip any possible attack in the bud ; if their own side get the ball they are expected to follow up to support the backs in passing. In most teams players are now specially chosen as wing forwards for their ability to break away quickly, and at the right moment, and for their instinct to see at once where they are likely to be of most use in open play. The New Zealand team which visited Great Britain in rqo5 demonstrated the possibilities of wing forward play. Their cap tain, David Gallagher, used as a rule to take no part in the scrum mage, but stood outside it, ready to go in any direction as the ball was gained or lost by his forwards. Though the idea and prin ciples of wing forward play were then entirely unknown in Eng land, Gallagher prophesied that they would soon become established. At first, like previous developments, the wing for ward was anathematized as a curse to the game, but he has now been accepted as an inevitable consequence of the general ten dency towards speeding up the play.

Until the formation of the Rugby Union in 1871 the Rugby school laws of the game were the only ones in existence, and they were so complicated that teams generally compromised and made rules of their own, so that when they played each other it was necessary for the captains to meet and agree as to how they should play. Even when the Rugby Union drew up a revised code of laws they were not properly understood by players for some time, and though many modifications and alterations have since been made, complete uniformity in interpretation has so far never been attained. The Rugby Union produced an entire re-draft of the laws in 1926, but the new form did very little to simplify them.

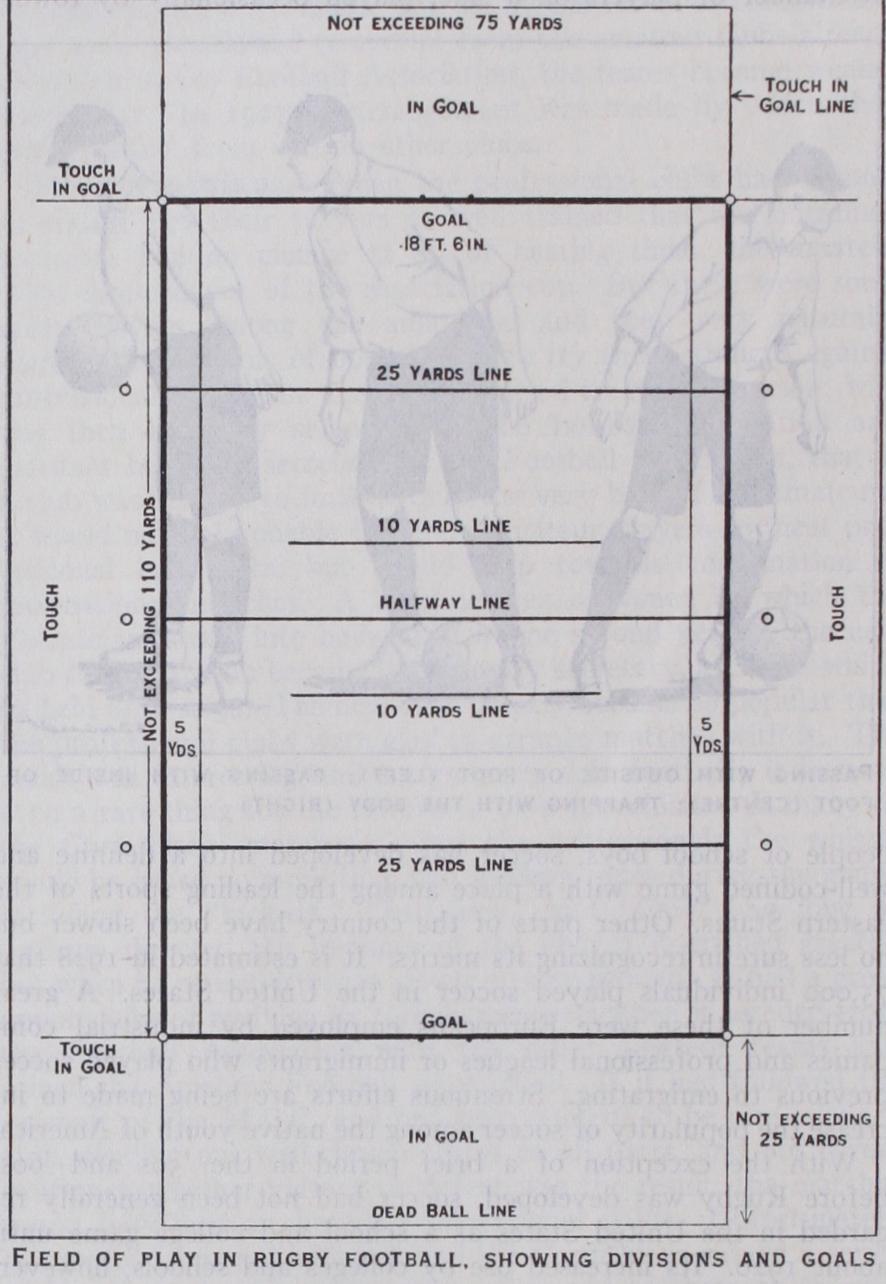

The Field of Play.

A plan is here given showing the dimen sions of the field of play and the method of marking it out ; and though it looks complicated, it is really very simple. The ten yards line, for instance, concerns only the kick-off from the middle of the field, which takes place at the beginning of the game and after every score. The ball must be kicked as far as or beyond the ten yards line, and none of the opposing side may advance over that line until the ball has been kicked. The 25 yards line similarly has very little to do with the play, except when the ball has been made dead behind the goal line other than by means of a score. The defending side may then take a drop kick from any point behind the 25 yards line, and the opponents may not advance over the line. The broken line marked five yards inside each touch line was introduced in 1926 in connection with an alteration in the laws providing that when the ball goes over the touch line it must be thrown in at least five yards. The goal line is the most important line on the field, since a try may be scored anywhere in the area between it and the dead ball line. The ball is in play in this area until a player touches it on the ground with his hand, or it is kicked over the dead ball line or the touch-in-goal lines. On most big grounds the dead ball line is marked at the maximum distance of 25 yards behind the goal line, but it varies on some grounds which are not large enough to permit of the maximum distance being used. There is no recog nized height for the goal posts and they are found of various heights on different grounds. When the United Services Rugby team was formed, and Lord Fisher, then First Lord of the Ad miralty, was appealed to for support he is said to have replied, "Certainly; and the United Services shall have the tallest goal posts in England"—and he at once sent out an order for them to Portsmouth Dockyard. It is an advantage to have the tallest possible posts, for as the ball may be kicked at any height over the cross-bar to score a goal, it is often difficult to judge a kick if the posts are short.

Points in the Game.

Though the play in detail is frequently very complicated, the game can be followed easily if one or two of the chief features are understood. Two of the cardinal princi ples are that a player may never pass forward, and that, with certain reservations, he may take no part in the play while he is in front of the ball when it is being kicked or carried by one of his own side. These rules sound simple enough, but in practice the second of them, which relates to off-side, is complicated by various provisions- and conditions. The enforcement of both rules depends solely on the opinion of the referee. In most of the other rules of Rugby the referee has only to deal with plain questions of fact. For certain deliberate infringements or unfair play, he may award a penalty kick to the opposing side ; other wise the game is resumed after an infringement by means of a set scrummage, the ball being put into the scrummage by the half-back on the non-offending side. A player may be tackled only when in actual possession of the ball, and must then play the ball; he is considered to have been tackled only when he is so held that there is a moment when he cannot pass or play the ball.

Kicking.

There are three distinct methods of kicking the Rugby ball—the place kick, the drop kick, and the punt. The place kick is a simple kick at the ball after it has been placed on the ground for the purpose. It is used in kicking at goal after a try, and is generally employed in attempts to score from penalty kicks. The drop kick is made by letting the ball fall from the hands to the ground and kicking it almost simultaneously, actu ally just as it is rising. A goal may be scored by the use of a drop kick from any part of the field during the play, and a drop is frequently used for penalty and free kicks. The punt, or kick at the ball before it touches the ground, is used chiefly for kick ing into touch. There was once a time when a deliberate kick into touch met with howls of derision from spectators, but it has come to be one of the most applauded features of the Rugby game.

Scoring.

Many changes have been made from time to time in the methods of scoring in the Rugby game, but the goal kicked from a try has always been supreme. At one time a match could not be won unless a goal was scored, no matter how many tries had been gained, since the basic significance of a try was that the side which obtained it had the privilege of "trying for a goal." The first change came in 1875, when it was ruled that if neither side had an advantage in goals, a match should be decided by a majority of tries. This was still unsatisfactory, for one goal would still beat any number of tries. In 1886 a system of scoring by points was introduced, and three tries were made equal to a goal. Five years later another change was made, two points being awarded for a try, and five for a goal; and in 1905 the present system was adopted, with scoring values as follows: A try-3 points ; a goal from a try (in which case the try does not count)-5 points; a dropped goal, other than from a free kick or penalty kick-4 points ; a goal from a penalty kick-3 points ; a goal from a "mark"-3 points. The "mark" is the only occasion when a free kick, as distinct from a penalty kick, is given. It may be claimed by any player who makes a fair catch either direct from an opponent's kick, or when the ball is knocked forward—or thrown forward by an opponent.So many changes have taken place in the methods of play in the Rugby game that opinions are bound to differ widely as to the comparative merits of players who gained fame in their day. Some of the older players shone perhaps with a special glamour because they were pioneers of new methods, and the players of one generation will nearly always champion their par ticular stars against all others. All that can be done in this ar ticle is to indicate some of the most outstanding players of their times.

Full-Backs.

By general consent two of the best full-backs the game has ever seen were H. B. Tristram and H. T. Gamlin. It is impossible to compare them in any way, for Tristram played in the days when there were only three three-quarters, while Gamlin did not appear until four three-quarters were played and the game had changed a great deal. Both were particularly noted for their deadly tackling, and Tristram is still remembered for the way in which he saved the game for England in 1887 by stopping the Herculean rush of W. E. Maclagan, the greatest Scottish three-quarter-back of that time, on the goal line. Some of the old full-backs were wonderfully long kickers, and among those who excelled in this way were F. J. Byrne, who played for England in the middle '9os, and W. J. Bancroft, the most fa mous of Welsh full-backs, who played in 33 international matches from 1890. Bancroft was a particularly fine drop kicker and an extremely clever player in every way. One of the very safest of full-backs was A. R. Smith, who played for Scotland from to 1900, and was an unusually fast runner. Among more modern full-backs W. R. Johnston, who played 16 times for England between 1910 and 1914, was undoubtedly a great back, who was hardly ever known to misfield the ball, even in its most greasy state. Since the war three fine full-backs have appeared in B. S. Cumberlege (England) who always inspired the players in front of him with complete confidence in everything he did ; W. E. Crawford (Ireland), a player of unsurpassed brilliance in his day but not so consistent as Cumberlege; and D. S. Drysdale (Scot land) , a clever player with very safe methods.

Three-quarter-backs.

Among the earliest three-quarter backs when the game became organized, Lennard Stokes, a younger brother of F. Stokes, the first English captain, was both a great player and an outstanding personality in the game. He began playing when teams had only one three-quarter and he saw the increase to two three-quarters, and then to three. W. E. Maclagan, who made an equally great name in Scottish Rugby at that time, was tremendously strong and his tackling was a terror to opponents. Mr. R. W. Irvine, who captained the Scottish team in his time, wrote "I would rather fall into the hands of any back in the three Kingdoms than into those of Maclagan." But the foremost attacking three-quarter of the '8os was undoubtedly A. E. Stoddart, the great cricketer. Possessed of great speed, he had an extraordinary faculty for running through his opponents, who would seem hypnotized. While Stoddart was playing for England, Wales produced A. J. Gould, whose daring agility and versatility earned for him the soubriquet of "monkey" ; and hard on his heels came E. Gwyn Nicholls, perhaps the most famous of Welsh three-quarters. At that time the four three-quarter system had not long been adopted, and Nicholls was largely instrumental by his play at centre three-quarter in bringing it to a perfection that will long be remembered in Welsh Rugby. He was a player with a born instinct for making openings for his colleagues, and always seemed to do things a little quicker than any other player. Between 1896 and 1906 Nicholls played in 24 international matches. J. E. Raphael, who played for England from 1902-06, was a three-quarter who always kept his opponents wondering what he would do, for he had an instinct for making the best use of an opening and had a swooping, dodgy run which made him very difficult to tackle. J. G. Birkett was another out standing personality in English Rugby for many years in the early part of this century, and opponents always held him in great respect, for he had a fine physique, of which he knew how to make the best use in running and tackling. Scotland had a player of conspicuous all-round ability in K. G. MacLeod, and Ireland in Basil Maclear. But the player who was most prominent for several years before the World War was R. W. Poulton Palmer. He was a great tactician and often won matches by daring strategy. C. N. Lowe has been perhaps the most remark able three-quarter since the World War, though he began playing for England in 1913. He must have been the lightest wing three quarter in history for he never weighed more than r ost. but he was very compactly built and could bring down much bigger players than himself because he timed his tackles so perfectly. He was a very elusive runner with a natural instinct for position. As a complete line the Scottish International three-quarters of 1924-25, I. S. Smith, G. P. S. Macpherson, A. I. Aitken, and A. C. Wallace, who all played for Oxford, stand out for their clever combination.Half-Backs.—The half-backs may well be considered in pairs, for although several players have shone individually, it is in partnerships that most of them have become famous. Scotland and England had two remarkable pairs at about the same time in the '8os in A. G. Grant-Asher and A. R. Don Wauchope (Scot land) and Alan Rotherham and H. T. Twynam. Wales has had two outstanding pairs in the brothers D. and E. James, who were extremely nippy, and were very clever in passing ; and R. M. Owen and W. J. Trew, with Owen a master-hand at evolving surprise tactics. Before them W. H. Gwynn was noted as the most sci entific half-back of his day, and after them there was T. H. Vile, a diminutive but brainy player, who improved on many of Owen's methods. Irishmen still think that Louis Magee, whose inter national career extended from 1895 to 1904, was the greatest half back Ireland has ever had; but R. A. Lloyd, who played from 1910 to 1920, was a very good second. P. Munro, of Scotland, and A. D. Stoop made a great pair in the Harlequin team a few years before the war. Stoop created new methods which revolutionized English half-back play, and had much to do with a revival of England's fortunes in international matches from 1910, when he first appeared. But there can be no question that W. J. A. Davies and C. A. Kershaw, who came together in the navy and England teams after the war, were players worthy to be compared with any of their predecessors. With a lithe, compact physique, Davies always had the quickness of genius in seizing his chances, and was a most elusive runner. When he had the ball no one knew what he might do, and he would sometimes drop a goal from an apparently impossible position. Kershaw, a strongly-built player, was not only able to give a much longer and swifter pass out from the scrummage than most other players, which helped Davies enormously, but he was a player of brilliant originality.