Anatole France

FRANCE, ANATOLE (1844-1924), whose real name was Jacques Anatole Thibault, French man of letters, was born in Paris on April 16, 1844. For 3o years French literature was dominated in the eyes of all the world by the fame of Anatole France. It is true that his influence declined in the last period of his life and that his ideas were questioned, but not his style nor the services rendered by him to the language. In his old age he was revered as a genius and a patriarch. No reputation since Voltaire's has been found comparable with his.

The son of a bookseller called Thibault, this youth who was to make illustrious the pseudonym of Anatole France started his career quite humbly. He was fond of literature, he was studious and erudite, but negligently preferred reading to writing. He composed publishers' puffs and contributed a weekly article signed "Gerome" to the Univers Illustre. For his own amuse ment he wrote verse, Les poernes dores (18 75) and Les noces corinthiennes (1876), which showed learning, charm and taste. In 1879 he published his first volume of stories, Jocaste et le chat maigre, and in 1881 his first novel, Le crime de Sylvestre Bonnard, which was acclaimed by the discriminating as delightful.

In 1883 he first met Madame Arman de Caillavet, with results that profoundly influenced his career. Mme. de Caillavet be came his life-long friend. She was clever and active; she had a host of acquaintances and her receptions were attended by the leading figures of literature and politics. She laboured for the fame of Anatole France, and she forced him out of his inertia into composition. The extracts from her correspondence with him prove the important share she took in his writings, and in the dedication of Crainquebille (19o4) Anatole France could say : "To Madame de Caillavet, this book which I should not have written without her help, for without her help I should write no books." For 4o years Anatole France poured out a series of lively. solid, graceful and profound works. There are the pungent and mis chievous short stories, Balthazar (1889), L'etui de nacre (1892), Le puits de Sainte-Claire (1895) ; the meditative and critical books, Les opinions de Jerome Coignard (1893), La vie litteraire (4 vol. 1883-92) ; a philosophical novel, La rotisserie de la Reine Pedauque (1893) ; an historico-philosophic novel, Thais (189o), describing Alexandria at the beginning of our era and contrast ing the ideals of dying paganism with those of nascent Chris tianity; an admirable novel on the French Revolution and the Terror, Les dieux ont soif (191 2) ; a society novel, Le lys rouge (1894), a powerful study of jealousy set amid the artistic treas ures and lovely vistas of Florence; then the series of political satires, the four volumes of L'histoire conternporaine—L'orme dry mail (1897), Le mannequin d'osier (1897), L'anneau d'amethyste (1899), M. Bergeret a Paris (1901), where Anatole France cre ates the legendary -figure of M. Bergeret and portrays society before and during the Dreyfus affair; novels of a revolutionary tendency, Sur la pierre blanche (19o3), L'ile des Pingouins (1908), La revolte des anges (1914), a biography of Joan of Arc (1909 ; lastly the reminiscences, Le petit Pierre (1918), La vie en Fleur (1922). Such is the sum of this work admirable in its wealth and variety.

The philosophy of Anatole France developed during the course of his career. Until 190o he was primarily a sceptic. As Voltaire's spiritual son, he delighted in the play of ideas and observed with out pity the stupidity and the silliness of men. He probed the past and the present and spared no example of human inconsist ency, error or weakness. Les opinions de Jerome Coignard gives the reader much pleasure, so witty and mischievous is the author, and gives him, too, a complete lesson in scepticism. The same remark may be passed on Les dieux ont soif, where Anatole France considers almost exclusively the failures of the French Revolution. At this time the author seems to have kept respect for beauty alone, the beauty of natural or artistic forms or of such superior intelligence as was shown in the great Greek and Latin writers. Meanwhile he beamed indulgently upon an im perfect universe. As he believed in nothing, he did not believe in a better or a worse. In the writings prior to 190o may even be found conservative and aristocratic maxims. A supreme indif ference inclined him to accept what is rather than risk what might be.

On the outbreak of the political crisis of 1900, his temper changed. He was then seen to show a preference for the pro gressive parties, and little by little went on to the revolutionary parties, which became honoured by his support. He was no ora tor; words came slowly, and neither his mind nor his phrases were of the kind likely to be popular. The part taken by him at public meetings was undistinguished, being limited to signing manifestos and applauding resolutions, especially those with an international objective. He was more powerful with his pen. An opponent of Church and State, he seemed to put his faith in the people and to expect the world to be renewed by some kind of revolution. On this point his ideas remained rather vague. In one of his books, Sur la pierre blanche, he ends the description of future society with a dreadful cataclysm that destroys every thing, and here he is nearer to nihilism than to socialism. The World War changed the trend of his thoughts. As he was too old to serve in the field he wanted at least to show his good will and asked to be employed in a Tours office. This great upheaval left him uncertain concerning the destinies of humanity. Perhaps extreme scepticism is not for long tolerable, and Anatole France felt the need of escape into a revolutionary faith which he refused to define, leaving it a mere aspiration.

What is indisputable is the quality of Anatole France's art, The younger generations, tried by war, and witnessing the conse quent political difficulties, ill comprehend the detachment of dilettante M. Bergeret. They need more moral discipline, they believe more in virtue and action. But they do not deny the master who charmed their elders with his graceful wit and magic phrases. As a storyteller, in lucidity of thought and form, Ana tole France is incomparable. In his style, too, there is a sweet ness, an almost voluptuous grace, which distinguishes his phrases from those of any other writer. He owed much to Voltaire, much to Renan, much to the old French romances, to memoirs and to chronicles. He had read and remembered much; but what he borrowed he made his own ; all was changed, and for the better, by his style and interpretation. He translated into a pungent idiom all that could delight or stimulate the intelligence of his cultured contemporaries. He was a deep admirer of classicism, and to the end of his life, when he mentioned Moliere, Racine or Stendhal his conversation or his writing attained their richest substance and most pleasant harmonies.

He makes another strong claim on the attention of posterity. He was the finest flower of the Latin genius. His knowledge of antiquity was great, and his work contained the essentials of Greek and Latin wisdom. He portrayed in Thais characters who distil the philosophy of the ancients. He put into the mouth of Jerome Coignard maxims which likewise represent the sum of the meditations and arguments common to antiquity.

Lastly, in all periods of his career, whatever his theories, he was a deep student of human nature. He expressed in magic words most of the wisdom that may be acquired from the obser vation of life and the reading of history. He created characters who persist in the memory—Jerome Coignard, Jacques Tourne broche, M. Bergeret, Madame Martin Belleme, Catherine, the lace worker, Paphnuce, Nicias, Evariste Gamelin. He described what was comic and evil in mortals. He described, too, what was august in man, sacred in man's labours and sufferings. Though he lacked enthusiasm and ardour, his critical intelligence did not prevent him from brooding over human misery, and in the story of Crainquebille he showed his heart. While humbling himself before the invincible forces of fate and lust, he dedicated his work now to irony—which brought brightness into his life—and now to pity—which at other times reminded him that life deserves a serious, a solemn attention. And so he became twice fortunate, for he was at once a subtle artist acclaimed by the critics and a universally respected publicist who influenced the simple-minded. He died at Tours, Oct. 13, 1924.

BIBLIOGRAPHY.-M. Gaffter, Les theories sociales d'Anatole France Bibliography.-M. Gaffter, Les theories sociales d'Anatole France (1923) ; G. A. Masson, Anatole France; son oeuvre (1923) ; M. le Goff, Anatole France a la Bechelleni (1924) ; C. Maurras, Anatole France, politique et poete (1924) ; J. L. May, Anatole France, etc. (1924) ; J. Roujon, La vie et les opinions d'Anatole France (1924) ; G. Truc, Anatole France, l'artiste et le penseur (1924) ; J. J. Brousson, Anatole France en pantoufles (1925) ; G. des Hons, Anatole France et Racine (1925) ; J. L. Dirick, Franciana, Opinions, anecdotes, pensees de M. Anatole France (1925) ; G. Girard, La Jeunesse d'Anatole France (1925) ; R. Johannet, Anatole France est-il grand ecrivain? (1925) ; H. de Noussanne, Anatole France, philosophe sceptique (1925) ; N. Segur, Conversations avec Anatole France, etc. (1925) ; J. Tharaud, Monsieur France, Bergeret et Frere Leon (1925). The works of Anatole France have been translated and edited by Frederic Chap man and James Lewis May and published by The Bodley Head, London. (A. CH.) FRANCE, a country of western Europe, situated between 51° 9' and 42° 23' N. and 4° 42' W. and 8° E. Its boundaries on the north-west (the English channel) and west (Bay of Biscay) are the sea, on the south its frontier is a line based upon the main ridge of the Pyrenees, on the south-east it borders the Medi terranean. The southern part of the eastern frontier is based upon the crest lines of the Maritime, Cottian and Graian Alps, pass ing east of Mt. Blanc along the eastern scarp of the Chablais to the south shore of the lake of Geneva. Leaving to Switzerland Geneva and its district and a strip along the north-western shore of the lake, the frontier goes along the Jura ridge to the Doubs river soon after reaching which it alters its character. The part described thus far is either sea or watershed, allowance being made for a few compromises as regards watershed lines when large valleys have been cut back through the watershed. The remainder of the frontier lacks this definite physical character and is a result of many historical processes so complex that the relation to physical geography is often obscured. After leaving the Doubs it bends west bringing Switzerland at Porrentruy to the north-western foot of the Jura, bending back again it goes to the vicinity of Basle and then along the Rhine (since the retro cession of Alsace-Lorraine after 1918) to a point east of Lauter burg. In this section the Rhine, flowing along the broad valley bottom, has long formed a marked boundary between the com munities on either side.

Leaving the Rhine the frontier runs west-north-west to the north side of the Strait of Dover. In its course it leaves most of the Saar valley outside, runs along the French side of the Ardennes, bends northward down the Meuse to give France the fortress of Givet, and then cuts across the slopes of Hainault and the Flemish plain to the sea a few miles north-east of Dun kirk; in this last section it runs parallel to and some 20-30 m. north of the hills of Artois. France forms a remarkably compact block rather over 600 m. from the coast north of Dunkirk to the most distant point of the Pyrenean frontier and somewhat less from the extreme point of Brittany (Cap. St. Mathieu) to the frontier east of Lauterburg. The area is now 212,659 sq.m., as against 207,170 sq.m. before 1918, the area of Corsica (3,367 sq.m.) being included in both totals.

Geology.—Many years ago it was pointed out by Elie de Beau mont and Dufrenoy that the Jurassic rocks of France form upon the map an incomplete figure of 8. Within the northern circle of the 8 lie the Mesozoic and Tertiary beds of the Paris basin, dipping inwards; within the southern circle lie the ancient rocks of the Central Plateau, from which the later beds dip outwards. Outside the northern circle lie on the west the folded Palaeozoic rocks of Brittany, and on the north the palaeozoic massif of the Ardennes. Outside the southern circle lie on the west the Mesozoic and Tertiary beds of the basin of the Garonne, with the Pyrenees beyond, and on the east the Mesozoic and Tertiary beds of the valley of the Rhone, with the Alps beyond.

In the geological history of France there have been two great periods of folding since Archaean times. The first of these occurred towards the close of the Palaeozoic era, when a great mountain system was raised in the north running approximately from east to west and another chain arose in the south, running from south-west to north-east. Of the former the remnants are now seen in Brittany and the Ardennes; of the latter the Cevennes and the Montagnes Noires are the last traces visible on the sur face. The second great folding took place in Tertiary times, and to it was due the final elevation of the Jura and the Western Alps and of the Pyrenees. No great mountain chain was ever raised by a single effort, and folding went on to some extent in other periods besides those mentioned. There were, moreover, other and broader oscillations which raised or lowered extensive areas without much crumpling of the strata, and to these are due some of the most important breaks in the geological series.

The oldest rocks, the gneisses and schists of the Archaean period, form nearly the whole of the Central Plateau, and are also exposed in the axes of the folds in Brittany. The Central Plateau has probably been a land mass ever since this period, but the rest of the country was flooded by the Palaeozoic sea. The earlier deposits of that sea now rise to the surface in Brit tany, the Ardennes, the Montagnes Noires and the Cevennes, and in all these regions they are intensely folded. Towards the close of the Palaeozoic era France had become a part of a great continent ; in the north the Coal Measures of the Boulonnais and the Nord were laid down in direct connection with those of Belgium and England, while in the Central Plateau the Coal Measures were deposited in isolated and scattered basins. The Permian and Triassic deposits were also, for the most part, of continental origin ; but with the formation of the Rhaetic beds the sea again began to spread and throughout the greater part of the Jurassic period it covered nearly the whole of the country except the Central Plateau, Brittany and the Ardennes. Towards the end of the period, however, during the deposition of the Port landian beds, the sea again retreated, and in the early part of the Cretaceous period was limited (in France) to the catchment basins of the Saone and Rhone—in the Paris basin the contem poraneous deposits were chiefly estuarine and were confined to the northern and eastern rim.

Beginning with the Aptian and Albian the sea again gradually spread over the country and attained its maximum in the early part of the Senonian epoch, when once more the ancient massifs of the Central Plateau, Brittany and the Ardennes, alone rose above the waves. There was still, however, a well-marked differ ence between the deposits of the northern and the southern parts of France, the former consisting of chalk, as in England, and the latter of sandstones and limestones with hippurites. During the later part of the Cretaceous period the sea gradually retreated and left the whole country dry.

During the Tertiary period arms of the sea spread into France —in the Paris basin from the north, in the basins. of the Loire and the Garonne from the west, and in the Rhone area from the south. The changes, however, were too numerous and complex to be dealt with here.

In France, as in Great Britain, volcanic eruptions occurred during several of the Palaeozoic periods, but during the Mesozoic era the country was free from outbursts, except in the regions of the Alps and Pyrenees. In Tertiary times the Central Plateau was the theatre of great volcanic activity from the Miocene to the Pleistocene periods, and many of the volcanoes remain as nearly perfect cones to the present day. The rocks are mainly basalts and andesites, together with trachytes and phonolites, and some of the basaltic flows are of enormous extent.

France, situated between the Mediterranean sea on the south east and the Atlantic and English channel on the west and north furnishes natural routes via the Rhone-Saone over the Cote d'Or scarp to the Seine, and via the Garonne from sea to sea, and thus continues the westward routes of the Mediterranean, a fact of the utmost importance throughout the country's history. As, also, the Strait of Dover is the natural westward end of the European plain, France continues southward the routes west ward along that plain; and this fact has been of tragic conse quence to her. The relations of France to both these great routes of civilization and of war gives that country a special function as an intermediary between south and north, between Roman and non-Roman in Europe.

The natural units that make up the country include three great river basins, the Paris basin (Somme, Seine and Loire), the Rhone-Saone basin and the Garonne basin, set respectively north, east and south-west of a block of highland (culminating at Puy de Sancy in the Mont Dore, 6,188 ft.) that forms barely one-sixth of the total area of France and is called the Central Plateau. Whereas on the north the Central Plateau forms the southern framework of the very large Paris basin, while its north-eastward annexe, Le Morvan, contributes to the basin's eastern framework, the southern fringe of the plateau (Montagnes Noires) projects so far towards the Pyrenees that there is left only the narrow gap of Carcassonne. The lowlands of south France are thus markedly divided into Mediterranean or Rhone lowlands and Aquitainian or Garonne lowlands, using the river names broadly in each case.

The highland framework partly surrounding the Paris basin is continued beyond the Morvan by the lower Cote d'Or scarp,astride of which stretched the nucleus of Burgundy. Beyond this again the Vosges (4,668 ft.) and the Ardennes continue the framework and the changes effected by the treaty of Versailles have removed the frontier from the slopes overlooking the north-east of the basin to slopes at times looking down towards Germany. It is characteristic of the collecting streams of the north-east of the Paris basin, the Meuse and Moselle, that a complex history has diverted them away from the basin northward to cut deep trenches in the Ardennes-Eifel highland block of old rocks. To the west the Paris basin is framed by the old rocks of Brittany and Nor mandy which, unlike those of the Central Plateau, reach above the i,000-f t. contour only in a few places. The coasts of Nor mandy and Brittany show the effects of a sinking movement which has given them long estuaries and fringing„ islands, Re, Oleron, Belle Ile, Houat, Hoedic, Ile de Groix, Iles de Sein, Ouessant, the Channel Islands, etc. This western area of old rocks and maritime activities constitutes a region of France to be added to the four (the three great basins and their frameworks, and the Central Plateau) already mentioned. Alsace constitutes a sixth, being on and under the Rhineward slope of the Vosges and thus right beyond the Paris basin; to this region also belong parts at least of Lorraine. Where the mountain framework of a basin is broad, as on the east side of the French Rhone, one might speak of still another region, that of the high mountains. One might also note that the old rocks of the Massif des Maures, and especially their seaward southern slopes, can be named as a small region apart, but these are merely outstanding examples to illustrate the possibilities of indefinite subdivision and com plication of any classification.

The Rhone-Saone Basin.—The Rhone-Saone basin is a long north-south corridor with the Alps and the Jura on the east, ranged in a line that shows how the mountain folds advancing westward have been stopped by the resistance of the old mass of the Central Plateau and the Morvan. The river runs along this corridor near the foot of the steep edge of the Central Plateau. The corridor is narrow for a considerable part of the lower course of the Rhone where the Alpine folds come nearest the Central Plateau, and this narrow portion makes a considerable break between Provence and Languedoc towards the delta, and the region above Lyons where the mountain f olds of the Jura make a convex curve between the north end of the Central Plateau and the south end of the Vosges. The Morvan and the Plateau de Langres are the heights on the west with the Cote d'Or as the limestone scarp under which runs the Saone. The feeders of the Rhone-Saone are of course mainly from the east, the Durance and Isere drain mountain areas in the Alps, the Rhone itself comes through from the east between the Jura and the main Alps and the Ain and the Doubs drain the Jura. The climate in the lower Rhone is one of summer heat and drought with a winter that is really mild only in places sheltered from the air currents streaming from the plateau (the Mistral winds) or from the mountains to the seasonal low pressure centre over the north-west Mediterranean. The spring is delightful apart from the Mistral which, however, does not blow very often at that time. It is a region in which, with wind screens, vines may be grown as field crops and the olive thrives about as far north as Pierrelatte. It is possible to grow choice early vegetables and there is pasture for cattle in the winter on the lowlands ; many are sent up to the highlands for the summer.

The lower Rhone is essentially a region of Mediterranean civilization with cities often of Roman and even pre-Roman heritage Orange, Avignon, Arles, Nimes, Marseille, etc. Farther north in the corridor the summer is less hot though again fairly dry, but the winter is too cold for the olive; the climate suits the mulberry about as far north as Lyons, beyond which the broader corridor has on and under its slopes facing south-east some of the choice vineyards of Burgundy. It is a region of vine and maize with stock and poultry farming on a good scale east of the Saone (in Bresse) and its forest growth is that of central Europe rather than that of the Mediterranean. Its cities are largely determined by their important lines of communication— Lyons, Dijon, Belfort. Both the Alps and the Jura have impor tant local capitals within their limits in France, the former Grenoble, the latter Besancon.

The Garonne Basin.

The Garonne-Dordogne basin is south west France, essentially a triangle framed by the Central Plateau, the Pyrenees and Bay of Biscay. The exposure to the sea gives a marked rainfall against the hill frame and this shows its effect in the great tributaries of the Garonne on both flanks, but especially on the left on which side Tarn, Aveyron, Lot and Dordogne have cut back long subparallel valleys. The Adour drains the south-west corner separately. The triangle mentioned above is incomplete ; there is a lowland way between the Central Plateau and the sea, the gate of Poitiers as it is often called. It has Bordeaux on its south-west side. There is also a narrow lowland way between the southern end of the Central Plateau and the Pyrenees, and this is the gap of Carcassonne with Toulouse on its west, Carcassonne itself at the critical point and Narbonne on the east. These facts concerning communications help to show how it is that this region has two major focal towns, Bordeaux and Toulouse. The climate is more moist than in the Rhone-Saone region and slightly less hot in summer; it does not suit the olive, but is famed for vines and maize, the wine being typically less ferruginous than in Burgundy. The chestnut abounds towards its northern border in the Perigord.

The Central Plateau.

In the west the granites give poor, cold soil; its Jurassic limestone areas (Causses) to the south-west and south are for the most part so bare as to be almost desertic, but parts may once have had a natural forest covering and the valleys are often rich. The volcanic ranges are often high and bare, but parts of the lands around them are famed for their pastures, while the upper courses of the Loire and Allier form bays in the north side of the plateau, in the beds of ancient lakes, the Allier flowing through the fertile Limagne which gives a site to the focus of a large region, a focus that once was Gergovia and now is Clermont Ferrand. On the high plateau it often happens that the river valleys are relatively broad with pastures and beech woods and a good population so long as they remain in the vol canic region, but farther down the river may cut through the hard ancient rocks and there it forms a gorge that is almost uninhab ited. There are small basins on the high plateau with historic towns that may have castles or churches on sharply outstanding volcanic rocks and the whole region may be said to have received many contributions to its life from the south, though legal and linguistic features have spread a good way up from the northern plain, through hillside foci such as Clermont Ferrand and Limoges.Apart from the coal area of St. Etienne the region is poor, and many of its departments have lost over io% of their population within the loth century. The wildness of some districts is illus trated by the fact that the wolf still lingers on the Central Plateau. The winters are severe on the heights and snow is abundant, the summer is moderate on the heights but hot in the lowlands. The contrasts between the olive-vine region below the plateau on the south-east and the mountain valleys, often between limestone hills, is a striking one and is the contrast of the setting of Roman Catholic and Huguenot elements in French religious life, though the psychological contrast has many other contributory factors besides the environmental one.

The Paris Basin.

This basin (of Seine and Loire) is floored by a succession of rocks arranged as a nest of saucers so that the successive saucer edges stand out as scarps facing outwards in each case. The command of any of these scarps by an army allows it to overlook the inward facing dip slopes. The centre is formed of Tertiary rocks including the corn growing calcareous plateau of Beauce (Pliocene) continued southward into the muddy Sologne, full of marshes and lakelets, and north-eastward to the Marne in the Brie, argillaceous save towards the Marne.The Eocene beds crop out around the Pliocene and vary in character, but are often sandy and forested, the f oret de Com piegne and other forests, which stretch south, east of the Oise and often overlook swamps where these Tertiary beds die out westwards near the Oise, forming a boundary zone of old between Belgica to the north and Celtica to the south. Several areas of this formation to the south are fairly barren and may hear a name allied to Gatine, and this frontier nature of the Eocene country is interesting as a factor of the rise of the French monarchy in the centre of the Paris basin. Around this centre comes zone after zone of rock, chalk in dry Champagne, Lower Cretaceous clays, followed by Upper Jurassic limestones and free stones sharply scarped at the Cote d'Or and fairly promi nently edged along the west bank of the Moselle. The Lower Jurassic or Lias with its less permeable rocks has gathered to itself long stretches of new courses in the north-east. Beyond this the framework of the basin varies, with the Ardennes on the north, but a belt of Triassic upland reaching the Vosges on the east. Between Ardennes and Vosges the Hunsriick and related heights reach the border of Lorraine, but on either side of these lat ter are ways to the Rhine that have made of Lorraine a region of transition and of strife. This border of the basin has hard winters and hot summers with a good deal of rain. The Vosges are high and wild enough to have wolves.

On the southern edge of the Paris basin is the Central Plateau but on the west the succession of outcropping rocks is not nearly so complete as on the east and the old rocks of the Armo: ican sys tem are reached giving the denuded and dissected plateau of west ern France with its sunken estuaries and its seaward outlook. here Brittany stands out, and to the south of it the Loire, draining the south of the Paris basin, cuts through the old rocks before it reaches its estuary below Nantes. It thus has a course which it acquired at some stage of its history through diversion and at the critical bend stands Orleans of great historic and strategic importance for that very reason. The fine valley to the south-west with its great châteaux and its tradition of cultured French speech is La Touraine. North of Brittany the west of Normandy is a part of this plateau of old rocks but beyond it the Seine estuary has given opportunities for maritime traditions in a country of the chalk rim of the Paris basin. The Seine draining the centre of the basin passes from the Eocene, with a good deal of forest near its border, to the chalk through which it has cut a rather deep trough so that there is an old frontier region along and on either side of the river, Le Vexin francais on the Eocene and Le Vexin Normand on the chalk.

On the north the Paris basin has a broad zone of chalk with anticlines and synclines that give rise to small scarps and valleys famous in the World War, and beyond lies the plain of Flanders, offering a much easier approach to the Paris basin than do the ways through Lorraine, with the result that Flanders is the greatest battlefield of European history. The focusing of the basin on Paris is extraordinarily complete and has contributed much to the centralization so characteristic of French life and organization, but the "ways" into and out of the basin via Flan ders, Lorraine and Belfort to the north and east have constrained Paris to maintain centralization in view of the needs of defence. The Paris basin, with a rainfall in many parts of only 23-25 in. and fairly cold winters, has a sunny summer of moderate warmth admirable for ripening wheat and permitting the growth of the vine in selected spots which accordingly grow choice fruit as at Reims, Epernay and Saumur. Towards the west the vine gives place to the apple and cider becomes the beverage, while stock-rearing becomes more prominent in agriculture under the influence of Atlantic rains. The Paris basin is essentially a corn-land rich in old market towns and dominated in unique fashion by the city of Paris.

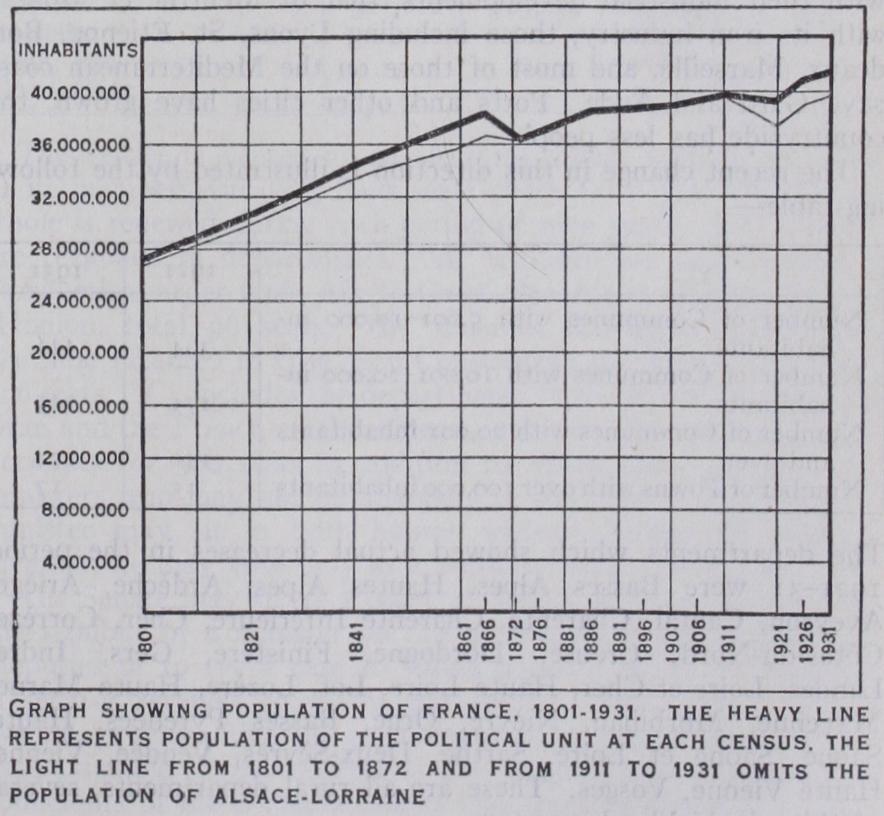

The work of Broca and of Collignon in the 19th century was of pioneer importance for the study of physical type in man kind. They showed that the central plateau and parts or the French Alps, together with parts of the surrounding lowlands, especially those south of the Seine and near the Garonne, were characterized by a short, thick-set, brown-haired, broad-headed population, which Broca called Celtic hut which have come to be known as Alpine. They arc a large element in the thrifty, hardworking peasantry, serious and deeply attached to their fields and villages. In the south-west, where the Basque lan guage (q.v.) survives, this type mingles with a long-headed dark element widely distributed around the western Mediterranean and known as the Mediterranean race; this is also found in Languedoc and Provence. In Burgundy and the Jura, one finds tall men, often fairly dark, with rather long faces. In the north of France the Alpine type is mingled with and influenced by tall fair types from farther north, the Franks being doubtless one of many contributing elements here. The Seine entry and the coasts of Normandy and Brittany also have tall, fair types of Scandinavian origin, and on the Breton coasts, for example near Binic and Paimpol, and in the Morbihan are tall, dark, broad-headed people comparable with similar groups found on the coasts of the Iberian peninsula, the west coasts of Great Britain, etc. ; these last are apparently descendants of men who spread along the Atlantic coasts in connection with some phase of pre historic trade. (See EUROPE, Ethnology.) France thus possesses considerable numbers of almost every physical type found in western Europe or, indeed, if the Bur gundians be allowed to be related to Dinaric types (see EUROPE, Ethnology), of almost all those found in Europe save the Arctic north and the Asiatic border. Collignon rightly emphasized the survival of types known from the late Palaeolithic, especially in the basin of the Dordogne. The contrasts between the stability of the totals of population in France in the 19th century and the phenomenal increase in Great Britain and between the ex treme urbanization of population in England and the large rural element in France are commonplace. They need to be under stood, however, with some reserves, for there has been in France a marked tendency to urbanization, continued and increased of late years. In the loth century also there has been an immense loss of manhood through the World War ; the maintenance of the totals is in part due to immigration of, chiefly, Italian, Spanish, Slavonic and Belgian elements. The following tables of popula tion illustrate the changes in the loth century and show that there has been a widespread decrease of population on the Central Plateau and in the east and south-east of the Paris basin as well as in the Garonne basin and the French Alps. The departments which show increases are two around Paris, that of the lower Seine with Le Havre and Rouen, those of Nord and Pas de Calais with their industrial developments, that of Meurthe et Moselle with its iron industry, those including Lyons, St. Etienne, Bor deaux, Marseille, and most of those on the Mediterranean coast save Gard and Aude. Ports and other cities have grown, the countryside has less people.

The recent change in this direction is illustrated by the follow ing table tion. France has become a country of immigration and the alien element is over io% in the following departments:—Alpes Mari times (about 28), Ardennes (over io), Aude (about 14), Bouches du Rhone (about 23), Herault (about 14), Isere (over 12), Meurthe et Moselle (about 17), Moselle (about 19), Nord (nearly i I), Pas de Calais (i4), Pyrenees Orientales (about 16), Var (over 14). The importance of immigration is further seen in the fact that Alpes Maritimes, Var, Bouches du Rhone, Herault, Pyrenees Orientales, Meurthe et Moselle, Nord and Pas de Calais are among the small number of departments that show increase of population in the loth century. The situation in France thus is that a very slow increase of native population with a gradual drift to the towns, away from the regions of difficulty, is going on alongside of a considerable movement of immigration, chiefly to industrial centres. The figures given above are from the official returns of the 1931 census.

The large cities of France in order of population are: *Show small decreases since 1926.

The birth rate was 20.5 per i,000 for the decade 1901-11 and by 1925 it had fallen only to 19.6, thus contrasting markedly with the British one which in 1927 was only 16.6. The death rate of over 21 per i,000 in the last decade of the 19th century had de clined to 17.6 in 1913, but rose as a result of war dislocation and was 18.1 in 1925. This is much higher than the British death rate has been for a long time. The conditions in France, with a still largely rural population, are such as to make care of infants and general sanitation more difficult than they are in general in in dustrialized Britain and the warm summers tend to make any defects of sanitation more dangerous still.

The occupations of the active population were as follows in 1921 :— The departments which showed actual decreases in the period 1921-31 were Basses Alpes, Hautes Alpes, Ardeche, Ariege, Aveyron, Cantal, Charente, Charente Inferieure, Cher, Correze, Cotes-du-Nord, Creuse, Dordogne, Finistere, Gers, Indre, Landes, Loire-et-Cher, Haute Loire, Lot, Lozere, Haute Marne, Mayenne, Morbihan, Nievre, Orne, Basses Pyrenees, Haute Saone, Saone et Loire, Sarthe, Deux-Sevres, Vendee, Vienne, Haute Vienne, Vosges. These are all rural departments, several of them in highland country.

France has a total population of 41,834,923, or about 196.7 per square mile, a relatively low density for a country of old settlement and varied resources like France. The total in 1921 was 39,209,766, but of this increase of 2,625,157 no less than 1,340,464 was due to an increase in the number of aliens from 1,550,459 to 2,890,923 or rather more than 6.9% of the popula The liberal professions show a marked increase and domestic service a marked decrease as compared with the early part of this century, changes that are noticeable in many countries. Transport work also occupies many more than it did 25 'years ago because of the road motor.

Constitution.

On Sept. 4, 187o, a republic was proclaimed in France and the main points in the national organization were fixed by the constitutional laws of 1875, with amendments of detail made in 1879, 1884 and 1926. The Constituent National Assembly is formed of the Senate and the Chamber of Deputies (v. inf.) sitting together at Versailles, and this assembly has charge of the constitution and also meets to elect the president of the republic who is eligible to hold office for seven years and may be re-elected. He has to be elected by an absolute majority of votes cast in the National Assembly. The president of the council of ministers (Angle "premier") may deputize for the president of the republic. The powers of the president of the republic include most of those usually exercised by a constitutional monarch. With the concurrence of the Senate he can dissolve the Chamber of Deputies, he can call it and the Senate to meet in extraordinary session and can adjourn them for a period not exceeding one month ; he can also send messages to them, and can refer their decisions back to them for reconsideration. He is responsible in principle for the making of wars and treaties. Every act of the president must be countersigned by a minister and his messages are communicated by a minister ; he chooses the president of the council of ministers and is liable to attainder only by the Chamber of Deputies and to trial only by the Senate constituted as a high court. With allowances for establishments and travel, the presi dent receives about two million francs per annum. The council of ministers is nominated by its president after the latter has been chosen by the president of the republic. The actual appointments are made by the latter who has the right to preside at the council, but there are unofficial cabinet meetings for most political pur poses and he does not attend these. A minister is responsible to the Senate and Chamber of Deputies, he can enter and claim to be heard in either chamber, he is responsible for a department of government, and responsible conjointly with his colleagues for the government in general. A minister is paid too,000 fr. per annum.The legislative chambers make laws, control the executive and exercise special powers mentioned under each ; the constitution provides for these sessions, adjournments and dissolutions. These chambers are the Senate and the Chamber of Deputies.

The Senate is eieeLed by an electoral college system, one-third of its members vacutmg their seats every third year so that the whole is renewed during each period of nine years. The "thirds" are reckoned in departments. "A" includes the departments in alphabetical order from Ain to Gard, also Alger, Guadeloupe and Reunion, total 96 seats. "B" includes the departments from Garonne (Haute) to Oise, also Constantine and Martinique, total t o6 seats. "C" includes the departments from Orne to Yonne, also Oran and the French establishments in India, total 98 seats. This accounts for 30o seats in addition to which there are seats for ministers who may not be members of the Senate, but though a minister may sit in both houses without necessarily being a member, he may vote only in a house of which he is a member.

The Senate may sit as a court of justice to try a president of the republic or a minister on the accusation of the Chamber of Deputies or to try a case in which national safety is involved. A senator receives 6o,000 fr. per annum. The electoral college system provides that in each department concerned a college shall assemble. It is composed of the deputies, general councillors, councillors of the arrondissements and representatives of munici pal councils, a council of t o members appointing one repre sentative, a council of 12 members two, a council of 16 members three and so forth. A senator must be a person with full civil rights and over 4o years old.

The Chamber of Deputies has at present 568 members elected every four years by France and Corsica, together with 16 mem bers elected by Algeria, and certain other French possessions abroad which are held to have reached an appropriate stage of development, Cochin China having one representative in the Chamber of Deputies, though it has none in the Senate. In France, apart from the territory of Belfort, which elects two deputies, there is one deputy for every 75,000 inhabitants and an additional one in any department with a residuum of more than 37,000 inhabitants.

The total number of deputies thus varies with the population. Every male citizen over years of age free of legal disabilities is a voter, provided he has resided six months in any one commune, but a deputy must be over 25. The voting is by lists for each constituency, an electoral college allocating the seats according to the votes cast; it is composed of general councillors nominated by the prefect of the department. Algeria has six deputies and other French possessions concerned have io, their numbers being fixed by law. A deputy receives fr. per annum.

The Senate and Chamber of Deputies both have legislative initiative and can demand that the president shall convoke them, one-half of the members of each having to agree for this purpose. Financial initiative and the power of accusation of a president or a minister before a court belong to the Chamber of Deputies alone. The members of former reigning families are not per mitted to become senators or deputies.

If a bill be presented to the Chamber of Deputies, it is referred to a bureau for examination and report, after which it must go through the chamber twice before being presented to the Senate. If it be presented to the Senate, it is referred to a commission of parliamentary initiative for report, after which it must go through the Senate twice before being presented to the Chamber of Deputies. Either the Senate or the Chamber of Deputies may pass a vote of no confidence in the Government, but the Govern ment resigns usually only on such a vote passed by the Chamber of Deputies. The Senate cannot be dissolved and the president may dissolve the Chamber of Deputies only with the consent of the Senate. Mention should here be made of the Council of State, the King's Council under the old monarchy, suppressed at the Revolution and re-established under Napoleon.

The Council of State (conseil d'etat) is the principal council of the head of the State and his ministers, who consult it on vari ous legislative problems, more particularly on questions of administration. It is divided for dispatch of business into four sections, each of which corresponds to a group of two or three ministerial departments, and is composed of (i) 32 councillors "en service ordinaire" (comprising a vice-president and sectional presidents), and 19 councillors "en service extraordinaire," i.e., Government officials who are deputed to watch the interest of the ministerial departments to which they belong, and in matters not concerned with those departments have a merely consultative position ; (2) 32 maitres des requetes; (3) 4o auditors.

The presidency of the Council of State belongs ex officio to the minister of Justice. The theory of "droit administratif" lays down the principle that an agent of the Government cannot be prose cuted or sued for acts relating to his administrative functions before the ordinary tribunals. Consequently there is a special system of administrative jurisdiction for the trial of "le con tentieux administratif" or disputes in which the administration is concerned.

Local Government.

According to the census of 1926, France, including Corsica, consisted of 90 departments, with 279 arron dissements, 106 having been suppressed in 1926, 3,024 cantons and 37,981 communes. Before the Act of 1926 the prefet of each department, elected by the president, was advised by an elected council, but now only the department of Seine has such a council, the others are grouped under 2 2 councils which are thus inter departmental. A department is divided into arrondissements, each with a sous-pre f et advised by a council elected by the cantons. Each commune has a mayor advised by an elected municipal council, with numbers regulated by the census returns save in the case of Paris, which has a council of 8o members; these coun 'The salaries of senators and deputies, which were only augmented to 6o,000 fr. from 45,000 at the end of 1928, are expected shortly to be again increased to 75,o0o fr.cils are re-elected every four years. The elected councils of the pre f et, etc., are chosen by universal suffrage. The pre f ets, sous pre f ets and maires de communes are nominees of the central authority and are entrusted with local headship of administration. Simplifications effected in 1926 were made for the sake of economy and in view of the diminution of population in many remote areas. The general council advising the pre f et superintends public property and assigns amounts of tax revenue to be raised by each arrondissement; it has no concern with political controversy. The sous-pre f et allocates amounts of tax revenue to be raised by each canton. Each canton is the seat of a justice of the peace and is the unit for elections to the general council and the council of the arrondissement. The maire is the executive officer of the com mune, looks after police, revenue, public works, civil registration, etc. In small communes he has one deputy, in larger ones he has more.

The ordinary judicial system of France comprises two classes of courts: (I) civil and criminal, (2) special, including courts deal ing only with purely commercial cases ; in addition there are the administrative courts, including bodies, the Conseil d'Etat and the Conseils de Prefecture, which deal, in their judicial capacity, with cases coming under the droit administratif. Mention may also be made of the Tribunal des Conflits, a special court whose function it is to decide which is the competent tribunal when an administrative and a judicial court both claim or refuse to deal with a given case.

Taking the first class of courts, which have both civil and criminal jurisdiction, the lowest tribunal in the system is that of the juge de paix. In each canton is a juge de paix who in his capacity as a civil judge takes cognizance, without appeal, of disputes concerning small amounts, but where larger amounts are concerned there is an appeal to the court of first instance. Criminal affairs are treated similarly. It is an important function of the juge de paix to endeavour to reconcile disputants who come before him, and no suit can be brought before the court of first instance until he has endeavoured without success to bring the parties to an agreement. Tribunals of first instance consider appeals from the juges de paix and initiate consideration of somewhat larger civil cases. An appeal from them in cases above a certain amount lies to the courts of appeal. When sitting as a criminal court the tribunals of first instance are known as correctional tribunals and their decisions are subject to revision by the courts of appeal. Tribunals of first instance formerly existed in each arrondisse ment, but in 1926 they were restricted to one in the capital of each department, the bigger departments having sections of the tribunal in other towns. Above the tribunals of first instance stand the 26 courts of appeal instituted for groups of departments at Paris, Agen, Aix, Amiens, Angers, Bastia, Besancon, Bordeaux, Bourges, Caen, Chambery, Dijon, Douai, Grenoble, Limoges, Lyons, Montpellier, Nancy, Nimes, Orleans, Pau, Poitiers, Rennes, Riom, Rouen, Toulouse. The departments of Haut Rhin, Bas Rhin, Moselle, that is, Alsace-Lorraine as returned to France after 1918, are not included in the above scheme, being still under special arrangements in several respects.

At the head of each court, which is divided into sections (cham bres), is a premier president. Each section (chambre) consists of a president de chambre and four judges (conseillers). Procur eurs-generaux and avocats-generaux are also attached to the par quet, or permanent official staff, of the courts of appeal. The principal function of these courts is the hearing of appeals both civil and criminal from the courts of first instance ; only in some few cases (e.g., discharge of bankrupts) do they exercise an orig inal jurisdiction. One of the sections is termed the chambre des mises en accusation. Its function is to examine criminal cases and to decide whether they shall be referred for trial to the lower courts or the tours d'assises. It may also dismiss a case on grounds of insufficient evidence.

The tours d'assises are not separate and permanent tribunals— they are held in the departmental capitals by a conseiller appointed ad hoc of the court of appeal upon which the department depends.

The

cour d'assises deals with serious criminal cases. The presi dent is assisted in his duties by two other magistrates, who may be chosen either from among the conseillers of the court of appeal or the presidents or judges of the local court of first instance. In this court and in this court alone there is always a jury of twelve. They decide, as in England, on facts only, leaving the application of the law to the judges. The verdict is given by a simple majority.In all criminal prosecutions, other than those coming before the juge de paix, a secret preliminary investigation is made by an official called a juge d'instruction. He may either dismiss the case at once by an order of "non-lieu," or order it to be tried, when the prosecution is undertaken by the procureur or procureur general. This process in some degrees corresponds to the manner in which English magistrates dismiss a case or commit the pris oner to quarter sessions or assizes, but the powers of the juge d'instruction are greater.

The highest tribunal in France is the cour de cassation, sitting at Paris, and consisting of a first president, three sectional presi dents and 45 conseillers, with a ministerial staff (parquet) con sisting of a procureur-general and six advocates-general. It is divided into three sections : the chambre des requetes, or court of petitions, the civil court and the criminal court. The cour de cassation can review the decision of any other tribunal, except administrative courts. Criminal appeals usually go straight to the criminal section, while civil appeals are generally taken before the chambre des requetes, where they undergo a preliminary examina tion. If the demand for rehearing is refused such refusal is final; but if it is granted the case is then heard by the civil chamber, and after argument cassation (annulment) is granted or refused. The cour de cessation does not give the ultimate decision on a case; it pronounces, not on the question of fact, but on the legal principle at issue, or the competence of the court giving the orig inal decision. Any decision, even one of a cour d'assises, may be brought before it in the last resort, and may be casse—annulled. If it pronounces cassation it remits the case to the hearing of the court of the same order as that from which it came.

Commercial courts (tribunaux de commerce) are established in all the more important commercial towns to decide as expedi tiously as possible disputed points arising out of business trans actions. They consist of judges, chosen from among the leading merchants, and elected by commercants patentes depuis cinq ans, i.e., persons who have held the licence to trade (see FINANCE) for five years and upwards.

In important industrial towns tribunals called conseils de prud'hommes, or boards of trade-arbitrators, are instituted to deal with disputes between employers and employees, actions arising out of contracts of apprenticeship and the like. They are composed of employers and workmen in equal numbers and are established by decree of the Council of State, advised by the minister of Justice. The minister of Justice is notified of the necessity for a conseil de prud'hommes by the pre f et, acting on the advice of the municipal council and the Chamber of Commerce or the Cham ber of Arts and Manufactures. The judges are elected by em ployers and workmen of a certain standing.

Police.

The judicial police under the maires and juges de paix include commissaires de police, the gendarmerie, and, in the country, gardes champetres and gardes f orestiers. These are specially concerned with the detection of criminals and the gath ering of evidence. Special branches include police des moeurs, police sanitaire, police politique, etc. The administrative police correspond more or less to the police constables of Britain and in clude the men commonly called sergents de ville, agents de police, etc. The Paris police includes in addition to the judicial and ad ministrative police above mentioned, an organization under the pre f et which has charge of the safety of the president of the repub lic and of the regulation of ceremonies, amusements, etc. There is also in Paris the police municipale concerned with traffic control and allied matters. There are depots de surete more or less corre sponding to British police stations, departmental prisons in most but not all departments, central prisons for long term prisoners, and convict stations—one at St. Martin-de-Re, and one in French Guiana. There are reformatories for young delinquents.Public assistance is given to the poor through bureaux de bien faisance which also have endowments and charitable contributions, and there are many ecclesiastical charities. Public institutions take charge of destitute children. An old age pensions scheme was inaugurated in 1910 and amended in 1912 and provides for con tributions from each worker up to his 6oth year with a State con tribution of Ioo fr. increased in cases where a worker has brought up at least three children to the age of at least 16. Maternity help has been legally established and, since 1923, 90 fr. per annum is given to a family of more than three children so long as the additional children are under 13.

Since 1905 Church and State have been separated by law and public funds are no longer chargeable with the salaries of clergy. Religious organizations are not allowed to organize public schools save in the case of special schools training persons for educational service abroad, and such organizations as the religious orders of the Roman Catholic Church must have the State's authorization before they can exist in France. These arrangements apply to the whole of France save the departments of Moselle, Bas-Rhin and Haut Rhin, which were called Alsace-Lorraine, 1871-1918, under German rule ; in these departments a special regime prevails. The historic religious organization of France is the Roman Catholic Church, the hierarchy of which in the country includes arch bishoprics at Aix, Albi, Auch, Avignon, Besancon, Bordeaux, Bourges, Cambrai, Chambery, Lyons, Paris, Reims, Rennes, Rouen, Sens, Toulouse and Tours. In addition to these 17 arch bishoprics there are 71 bishoprics and the tendency has been in the main to make the sees correspond with the departments. The sees are divided into deaneries and the ultimate unit is the parish served by a cure or desservant (incumbent) who may be assisted by a vicaire. The training for the priesthood is given in seminaires, the lower ones being in part equivalents of grammar schools, the higher ones more strictly theological colleges.

Protestantism has an interesting history in France having de veloped, chiefly under Calvinistic influences, in various centres in the 16th century, while Lutheran ideas spread in parts of the North-east (Montbeliard, etc.). The revocation of the Edict of Nantes in 1685 led to the depletion of the Protestant population which had enjoyed a measure of toleration under that edict, and was specially strong in some districts which had been Albigensian in the 13th century. With the re-establishment of ideas of tolera tion various British and other religious bodies founded groups in France and the following organizations now exist : Eglises re f ormees, Eglises re f ormees evangeliques, Eglise evangelique luth erienne de France, Eglise de la Confession d'Augsbourg (luth erienne), Societe centrale evangelique, Union des eglises evange liques libres de France, Eglise evangelique methodiste de France, Eglises baptistes de langue f ranQaise. In accordance with the law of separation of Church and State (19o5) the Protestants have formed associations cultuelles. There is a Protestant Federation with a lay president. The Protestants of France may number about i,000,000 souls, chiefly in Montbeliard, Alsace, Paris, the Cevennes, and a few isolated towns for the most part in the south.

The Jewish religion has adherents chiefly in certain cities such as Paris, Lyons, Nancy, Bordeaux, etc., and is organized on the basis of associations cultuelles. There are a few North African Mohammedans in France, many of them in and near Paris.

The foreign possessions of France are in two historic groups. First the remains of the old colonies, Saint Pierre and Miquelon, on the Canadian coast ; Martinique and Guadeloupe, with their dependencies, in the West Indies; Guiana in South America ; five enclaves in British East India, Pondicherry being the most impor tant ; Reunion, in the Indian ocean, near Mauritius, a relic of the match between Bougainville and Cook. These are, if one likes to call them so, the aristocratic colonies. The American and Indian colonies and Reunion have their deputies and senators in the French parliament. They are united with France by old bonds