Benjamin Franklin

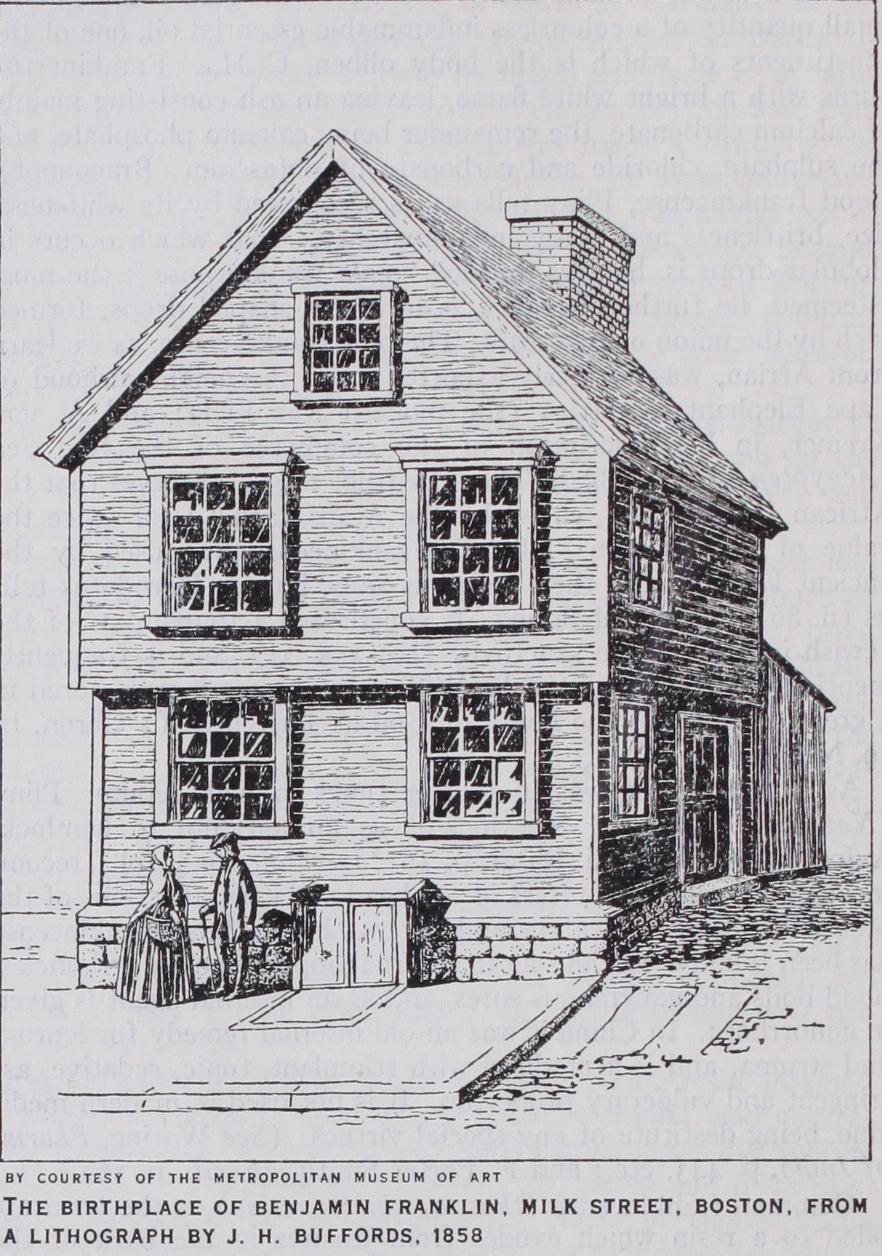

FRANKLIN, BENJAMIN (1 706-1790), American philos opher, statesman and man of letters, was born in Boston on Jan. 17, 5706 (old style, Jan. 6), and was baptized at once in the Old South church, thus beginning his life in a thoroughly puri tan environment. His father, Josiah Franklin, had come from England where he had worked first at Banbury as a dyer. There he married and had three children. About the year 1685 he lef t England and settled in Boston, Mass., then a city of 5,000-6,000 inhabitants. He gave up his trade of dyer and became a tallow chandler and soap boiler. He was a hardworking, serious and strong man, always much respected by his son Benjamin, who describes him minutely and affectionately in his autobiography: "He had an excellent constitution of body, was of middle stature, but well set and very strong; he was ingenious, could draw pret tily, was skilled a little in music, and had a clear, pleasing voice, so that when he played psalm tunes on his violin and sung withal, as he sometimes did in an evening after the business of the day was over, it was extremely agreeable to hear. He had a mechanical genius, too, and, on occasion, was very handy in the use of other tradesmen's tools; but his great excellence lay in prudential matters, both in private and public affairs." The family had been Protestant for a long time and Josiah Franklin was a Nonconformist.

Boyhood.

The first wife of Josiah Franklin died in 1689 and he married very soon after Abiah Folger, daughter of Peter Fol ger, one of the first settlers of the island of Nantucket, a broad minded, "godly, learned Englishman." By her Josiah Franklin had ten children, six boys and four girls. Benjamin was the last one of the boys. Boston was then a small city but a thriving and growing one, and Josiah Franklin gave a good education to each of his children. He sent Benjamin to a grammar school at the age of eight, intending him for the Church; there he kept him a year, sending him afterwards to George Brownell's school for writing and arithmetic. When the boy was ten his father appren ticed him to his own business, but Benjamin did not like it. He dreamed restlessly of the sea, and his father became aware that if something were not done quickly the boy would follow the ex ample of one of his elder brothers and leave suddenly. To prevent this he tried to find some business which would suit the character and fancy of his son. Finally he put him as apprentice with his half-brother James, who was a printer in Boston. Benjamin was then a healthy, sturdy and bold little boy. He was equally strong physically and mentally. He had learned to swim and do all kinds of physical exercises. But at the same time he had become a bookish lad and had read all the books he had been able to find or to buy, especially Bunyan's Pilgrim's Progress, Locke, On the Human Understanding, the Spectator (3rd vol.), Plutarch's Lives, Defoe's Essay on Projects and Mather's Essay to do Good.

From the age of 12 to the age of 17 he worked with his brother. James Franklin was young, eager to make a success and daring. He established a newspaper which was the rallying centre of the liberal minds of Boston at a time when theocracy and the ruling aristocracy of puritans were beginning to lose their supremacy. The New England Courant (established Aug. 17 21) has been called the "first sensational newspaper of America." It was of ten in trouble with the Government and James found himself at one time in such difficulties that he had to ask the boy to publish the sheet under his name (Feb. 11, 1723).

In this atmosphere of intellectual excitement and political strug gle Benjamin developed quickly. His first articles, the famous Dogood Papers, are full of juvenile charm, and, although in close imitation of the English Spectator, have a certain quality of intelligent realism and accuracy which is all their own. He quarrelled with his brother and would not listen to his father who tried to reconcile them. Finally he left the city with a young friend, Collins. He sailed for New York and Philadelphia, arriv ing in the latter city in Oct. 1723. He found a job as printer with a certain Keimer, a rather queer and unreliable man. The gov ernor of Pennsylvania, William Keith, noticing him for his appear ance, his industry and his reputation of learning, offered to help the boy to set up a printing press for himself. Benjamin went to Boston to try to get the permission and backing of his father, but the latter thought him too young and inexperienced. Having re turned to Philadelphia he was persuaded by Keith to go to London to finish his education as a printer and collect the things needed to establish a printing firm at Philadelphia. The governor had promised to give him a letter of credit and some useful letters of introduction, but being himself in trouble with the Penn family and having apparently a weak character, Keith failed to fulfil his promise and Franklin found himself in London with little money, no English friend, and no other means of livelihood than his trade (Dec. 1724).

Early Life as

worked as a journeyman printer at Palmer's printing house for about a year, then at Watts's print ing house, where he met a number of the men who became great in the English publishing world of the i8th century. He had sailed from Philadelphia with a friend, Ralph, a dissolute boy, who spent all their money, until they separated. At this period Frank lin seems to have been nearly an unbeliever. He wrote then and printed himself in a small edition his Dissertation on Liberty and Necessity, Pleasure and Pain (1725), in which he endeavoured to prove that everything we do is according to fate. The booklet attracted some attention and gave him a chance to meet some of the leaders of the deists, especially Mandeville. His pleasant appearance, his industry, cleverness and skill in swimming made him many friends and, had he stayed in England, he would doubt less have had a successful English career. He chose to go back to Philadelphia.He accepted the proposal of Denham, a wealthy Quaker mer chant who became interested in him and offered him a situation as clerk and bookkeeper in the store he intended to open in Phila delphia. After about 19 months in England Franklin sailed from Gravesend (July 21, 1726), and landed in Philadelphia on Oct. He was then 20 years old, but the formative period of his life was ended. He had seen and learned much. From his family he had received that earnest, hardworking temperament which helped him so much in his long life of struggle, difficulties and well-earned success. From the same origin and the Boston culture he seems to have derived that deep feeling for religion, prayer and morality, which after a short crisis was never to leave him. From his early readings, from the little group of Liberals in Boston, from his associations in London, he secured that intellectual impetus, that clearness and boldness of mind, too enthusiastic at the beginning of his life, but later tempered by moderation and good sense, which made him the most acute and broadminded thinker of his time. By 1726 Benjamin Frank lin had all these qualities and he continued to show them steadily for more than 6o years. After a few months in Denham's store both were taken ill and Denham died. When Franklin recovered, he went back to the printing business and hired out again to Keimer who used him to run his printing house while he himself took care of the stationer's shop (1727). The following year, with the co-operation of Hugh Mere dith, a fellow workman, he estab lished a printing house for him self and was able in ten years to make it the most flourishing business of this kind in the Eng lish colonies. It was not only the co-operation of a few friends, his untiring activity and common sense, which made his success, but also his imagination and ini tiative. He had planned to create a newspaper and purchased the Pennsylvania Gazette in Sept. 1729. It was then a dull, poorly printed sheet, appearing weekly. Franklin made it alive, liberal and amusing. Besides the news items, which were entertaining, well chosen or well invented, he wrote various articles and essays. The circulation at the beginning was small but finally became the largest in America, 8,000–io,0oo, and the advertisements, which he had developed from the time he took control of the paper, proved very profitable. In 1732 he wrote and sold his first Poor Richard's Almanack, the book which was to make his for tune. For many Americans of that time the Almanacks were the only publications bought regularly and read carefully. Franklin's Almanack, full of wisdom, wit and useful hints, was soon the most widely read in all the colonies. Later he collected the best of his maxims (17 5 7) and published them as the "Speech of Father Abraham" in the Almanack of that year.

Activity in Philadelphia.

In 173o Franklin became public printer for Pennsylvania, a position which added not a little to his social prominence and to his business. The same year (Sept. 1i30) he married Deborah Read whom he had loved as early as 1723. But when he went to England she thought he had deserted her (and he was not far from agreeing) and she married another man. This man having disappeared the two young people decided to become husband and wife. She seems to have made him a good wife; and Franklin reciprocated her affection. When they married Franklin already had a son (maybe by her?) to whom she was kind. Later they had another boy who died of smallpox (Francis Folger Franklin, and a girl, Sarah Franklin, born in who married Richard Bache, a young merchant in 1767. Franklin was a tender father and the death of his son was a life long sorrow to him. At the time that he was building his business and his fortune he did not forget his great moral and social aims. In 1727 he founded with several young men of Philadelphia a kind of club, resembling very much a freemason lodge. This little group known at first as the Leathernapron club, but always called by him "The Junto," played a great part in Franklin's life. It was there that he learned to be a leader of men and acquired his first group of staunch friends. With the help of this group, which grew rapidly, Franklin began to be known as a public man in Philadelphia. The pamphlet he published in favour of paper money (A Modest Inquiry into the Nature and Necessity of a Paper Currency, 1729), at a time when the colony was in great need of more currency attracted much attention. Gradually he became one of the most influential citizens of the growing city, respected for his thrift, his public-spirited activities and his wis dom. In 1731 he founded the Library Company, the first circulat ing library established in America. He had become a freemason (Feb. 1731) and in 1732 was elected grand master of the grand lodge of Pennsylvania, which broadened his scope of activity and influence. In 1736 he was chosen clerk of the Pennsylvania Assem bly (1736-1751) and the same year he organized the first fire company in Philadelphia, a much-needed institution where nearly all the buildings were of wood. In 1737 he was appointed post master at Philadelphia, a position which enabled him quite hon estly to give a new impetus to his newspaper and distribute it more easily.The field of his activities was constantly broadening. He was not only the first printer and bookseller of Philadelphia, he also established a printing office in New York in partnership with James Parker (1741), having previously done the same thing, in Charleston, S.C., in 1733, and later he sent an outfit to Antigua. He was also interested in a printing office in Kingston, Jamaica, and subsequently helped two of his nephews who had been his ap prentices to establish themselves as printers. In the end he had business connections with most of the English colonies in Amer ica : Boston, New Haven, New York, Charleston, etc. By these means and by a careful economy he acquired a competence and thought of retiring from active business. A Scotch journeyman, David Hall, who had been sent to him by his English friend, Peter Collinson, became his partner in 1748. "The partnership continued 18 years successfully for us both," Franklin wrote later. To give an idea of the prosperity of their industry one need simply quote the profits of his printing office, which during that time amounted to about Lr,000 a year.

As soon as he had Hall with him he found time to start a new line of activity. Franklin had always a curious and fertile mind and occasionally in the New England Courant, and the Pennsyl vania Gazette he printed little philosophical or scientific essays of his own, on earthquakes for instance; but he had previously never been able to devote much time to research, although since 1733 he had studied in his spare hours French, Italian, Spanish and Latin. In 1743 he founded the American Philosophical So ciety. He had invented a new kind of open stove, a great improve ment on its predecessors, but he was tempted to the more recon dite kinds of research. At a time when the discoveries of Mus schenbroek and his disciples and the recent experiments of the Leyden jar had attracted the attention of the whole world, Frank lin, in his modest and remote home in Philadelphia, began to experiment with a small apparatus sent to him from England by Peter Collinson . He was naturally versatile and as elec tricity was still in its very infancy, and the theories to explain it were most unsatisfactory, his accuracy and common sense led him to the discovery of the identity of lightning and electricity (1752). He was not the first to think of it but he was the first to prove it. He framed a new theory of electricity, involving the existence of two different kinds of electricity, which he called posi tive and negative, a division which still holds good. He finally invented a means of avoiding the disastrous effects of lightning, the lightning rod, which gave him a public prestige equalled by few scientists of the i8th century (1748-52) . In 1749 he retired from printing but continued to advise, help and back Hall. During his 21 years of active business he had been a good, pro gressive printer, issuing such interesting and useful books as the medical treatises of Cadwallader Colden, Essay on the Iliac Passion, Essay on the West India Dry Gripes, or the reprint of Richardson's Pamela (1744), the first novel printed in America; but his Poor Richard's Almanack was his best venture, as is proved by the innumerable translations and reprints. By 1900 75 English editions of the "Sayings of Poor Richard" were known, 56 French, 11 German and nine Italian, and the list is by no means complete. (See ALMANAC.) Entry into Politics.—His political career was equally bril liant and eventful. He was elected in 1748 a member of the city council and in 175o a member of the assembly of Pennsyl vania, to which office he was re-elected annually for 14 years. During that time he was one of the most active and efficient mem bers. He sided with what might be called the popular and pro gressive party. The most important question at issue was whether the estates of the proprietaries, the Penn family, should or should not pay taxes, as did the other landowners. The popular party and Franklin contended that they should, but the Penns flatly refused. Consequently parliamentary life in Pennsylvania was a long con flict. The enemies of the proprietaries were at the same time ardent patriots and looked to the Crown to make Pennsylvania a royal province. In the middle of this struggle two wars came and made the situation critical at times (1744-48 and The Quakers, in accordance with their principles, would not serve as soldiers or appropriate money for arms and ammunitions ; the Penns would give no money or scarcely any; the remaining in habitants saw no reason to pay money or fight for people who did not want to fight ; and finally the Germans, who had settled in large colonies in the western parts of Pennsylvania, were suspected of being pro-French, because many of them were Roman Cath olics. In the midst of all these difficulties Franklin proved himself a faithful subject of the king and a staunch loyalist. With the help of the middle class of Philadelphia and of his friends (the "Junto" and the Freemasons) he stimulated interest in the estab lishment of a militia and fostered the organization of an associa tion of volunteers for the defence of the city and province. To achieve this aim he wrote a strong pamphlet : Plain truth, or Serious Considerations on the present state of the city of Phila delphia and Province of Pennsylvania • In 1753 he was sent as a member of the commission from the council and assem bly to confer with the Indians of Carlisle with respect to a treaty to protect the western frontiers of Pennsylvania. In 1754 again he went to Albany as a commissioner for Pennsylvania at the con gress which met to confer with the chiefs of the "Six Nations" and to get their help against the French. Struck by the magnitude of the danger Franklin wrote his famous Plan for a Union of the English Colonies in America, which was finally turned down in London. In 17;5 he aided Gen. Braddock. who had been sent from England to attack the French in the west, to transport his army to the theatre of operations by establishing a system of transport. He did it at his own risk, as the province was occupied with internal disputes, which left no time for the war. After Brad dock's defeat and at a moment of panic he entered the military service and accepted the dangerous mission of organizing the north-western frontier which was constantly subjected to bloody raids by the Indians. When this danger disappeared the popular party decided to send Franklin to England to see if an agreement could be made with the proprietaries. He had planned for sev eral years to go to London ; see his old friends, meet his new scientific friends who had received with such warm enthusiasm the papers he had sent them : Experiments and Observations on Elec tricity made at Philadelphia in America (1751); Supplemental Experiments and Observations on Electricity (London, New Experiments and Observations on Electricity made at Phila delphia in America (1754). These books had attracted so much attention that he had received the Copley medal from the Royal Society in London, and a complimentary letter from Louis XV.

He was then a rich and influential man. His Gazette, to which he still contributed, was very widely read, and having been deputy postmaster-general for America since 1753 he could do much to circulate it all over the colonies, from Carolina to Massa chusetts. Although this post was a very difficult one, he hoped to make it useful both for himself and his country. He succeeded. After a few years the American post office, which had never brought any income to the English administration, began to pros per. From Aug. 1753 to Aug. 1756 there was a deficit of £678 7s. 2d. From Aug. 1761 to the beginning of 1764 there was a surplus of £2,070 1 2s. 3d. One of the most valuable evidences of Frank lin's devotion to the public interest (besides an improvement in Philadelphia street paving, street lamps and a hospital) was the Academy of Philadelphia, called first "The Academy and Chari table School of the Province of Pennsylvania," and later the "Uni versity of Pennsylvania." As early as 1743 Franklin had printed and circulated a paper Proposals for establishing an Academy. In 1749 he succeeded in getting the necessary support and the academy was established. Franklin delighted in it, although it was to be also a great source of annoyance. He had in mind when he proposed it the organization of a new and up-to-date institu tion, where the children of Philadelphia should be taught practical things and, especially, instructed in English. The English lan guage was for him the centre of the proposed education. But there he ran against a general prejudice of the upper classes of the i8th century. His money, his activity and his support were ac cepted but little by little his plan was changed, the academy was made a classical school, Latin was given the first place and English gradually allowed to drop. All Franklin's efforts against this only made him unpopular and were used against him by his enemies, mainly by William Smith, a clergyman, whom he had himself generously and imprudently introduced into the academy and made provost.

Visits

to England.—England received him cordially The University of St. Andrews conferred upon him the degree of doctor of laws in 1759 and the University of Oxford the degree of doctor of civil laws in 1762. He was already a member of the Royal Society (elected 1752), where he became influential. He had innumerable friends, some political or fashionable like Sir Francis Dashwood (Lord Le Despenser), Lord Shelburne, Sir Grey Cooper and later the elder Pitt, others more intimate and intellectual, like Priestley, Price and Sir John Pringle (the king's physician). His activities were manifold. But the most important was his work for Pennsylvania, for in 1760 he succeeded in per suading the Penn family to agree finally to some taxation of their estates. He published in London Some account of the Success of Inoculation for the Smallpox in England and America (176o), and in the same year his Parable against Persecution. In also he took part in the discussion concerning the conditions of peace England should ask or rather impose and wrote his famous pamphlet, The Interest of Great Britain considered with regard to her Colonies, which is thought to have had great weight in the de cision of the English ministry to retain Canada rather than Guadeloupe. In 1761 he made a tour of Holland and then re turned to Philadelphia (Nov. 1, 1762). His return was trium phant, but this was not to continue long. In the midst of the hap piness of the peace of 1763 the English colonies of America were thunderstruck by the bloody Pontiac war and other Indian trou bles. At the same time the new governor, John Penn, repudiated the agreement of 1760. The old quarrel started again and this time Franklin came out openly in favour of a radical change in the status of the province to that of a royal province. The elec tion of 1764 was most bitterly disputed. Franklin and his inti mate friend and adviser, Galloway, failed of re-election, but their party kept its majority and he was sent again to England, this time to ask openly that the king take over Pennsylvania.He sailed in November and started to work at once only to find himself in an awkward position. Just at the time when Pennsyl vania was throwing itself into the arms of the king the ministers of the king imposed upon the colonies a Stamp Act, the very idea of which was hated throughout America. So Franklin had at once to combat the ministers and to treat them as chosen patrons. Small wonder that things were not easy during these years. When the Stamp Act was passed, he thought that the best thing would be to accept it temporarily. This, however, was not the view of the people at home and he had to change his point of view, not without bitter criticism. Finally he was fortunate enough to see the Stamp Act repealed in 1766, largely through his efforts, and as a result of his famous examination before the House of Com mons (Feb. 1766). This success made him the best known of all Americans both in Europe and the New World. Georgia appointed him her agent in London in 1768 and Massachusetts in 177o. He visited Ireland and Scotland in 1771, where he was received with the utmost courtesy, especially by the learned circles of Edin burgh. He went to France in Aug.–Sept. 1767 and July–Aug. 1769, and to Germany (June, 1766). He found everywhere the same enthusiastic welcome.

His work did not give him much leisure. Immediately after the repeal of the Stamp Act new schemes and methods of taxing the American colonies were devised in England (Townshend's Acts, 1767). Franklin fought tirelessly against them, but every day his attitude as an ardent American, a faithful subject of the king and a good British citizen became more difficult to sustain. He thought he had found a way when he laid hands on a bunch of papers which proved that many of the most objectionable meas ures against the colonies had been taken on the advice of certain "American tories," especially Gov. Hutchinson of Massachusetts. Franklin thought it would be a master stroke to show the Ameri cans that if the English king, ministry and people had done offen sive things against America, they had at least the excuse of having been incited by people in America itself. If the English ministers had been farsighted they could have derived great advantage from this, but they saw in Franklin's act only an attack upon some of the most faithful servants of the Crown. Franklin had sent the letters to Massachusetts and had allowed his friends to circulate them. The assembly of Massachusetts had written a "Petition to the King for the removal of Gov. Hutchinson." This document was at once loyal to the king and bitter against Hutch inson, whose friends lost no time in instigating a counter intrigue. As a result Franklin was called before the privy council, exam ined, and insulted by Wedderburn, the attorney-general, who called him a thief (Jan. 17 74). A few days later he was dis missed from his office of deputy postmaster-general, and it was rumoured that his arrest was contemplated. He nevertheless stayed a little longer in England, then sailed for Philadelphia a famous but a beaten man. He had failed in what had been one of his chief purposes in life: to keep the British empire united and help America to grow inside the empire. • His Mission to France.—He came back to America with the prestige of having lost a high position and thrown away a brilliant career for the sake of his country. His situation, at one time rather unsafe because of the hostility of the upper classes in Pennsylvania and Massachusetts, was again prominent and solid. He was at once made a member of Congress, elected postmaster general of the colonies (1775), then chosen as one of the three commissioners of Congress to Canada (1776). He went to Mont real but could not stir up any enthusiasm in favour of inde pendence or an alliance with the Protestant colonies, and, after many dangers and great fatigue, returned to Philadelphia, where he presided over the constitutional convention of Pennsylvania. Congress elected him one of a committee to frame the Declara tion of Independence, which was written by Jefferson, but cor rected by Franklin. In Sept. 1776 he was chosen as one of three commissioners to France, whose help was sorely needed. And although the English cruisers, the winter weather and his old age made it a most dangerous enterprise, he sailed at once.

He arrived in France in Dec. 1776. His reputation as a scien tist and Liberal philosopher had preceded him and he was at once popular, but his task was not easy. He knew that the war would be prolonged and the help of France most needed. But he came to this absolute, Catholic and traditional monarchy as the envoy of rebel provinces to ask the assistance of Louis XVI. against a legitimate king, in favour of insurgents, who were Protestants, and had been for a century and a half the bitterest enemies of France in the New World. He had against him many prejudices, many principles; the prestige of England, the peaceful temper of Louis XVI. and his ministers, and the situation of France, which was in dire need of financial reforms and economy. Moreover, he had no assistance other than that of ignorant, clumsy or jealous Americans, and his grandson William Temple Franklin, a boy of 18, illegitimate son of William Franklin, governor of New Jersey for the king of England and a staunch Tory.

Franklin had lost his wife in Jan. 17 73. His only son had de serted him for the other side, his house and property were at times in the hands of his enemies. He was cut off from his English friends and many of his old friends in America were dead or had become Tories. In these tragic circumstances Franklin worked as courageously and as efficiently as if he had been a man in the prime of life. He had been a member of the French Academy of Sciences since 1772, and had many friends among the French sci entists and philosophers at a time when philosophy was the fash ion in France. He made use of them and met through them all kinds of people. He fascinated everybody, mostly the ladies, who were not a negligible part of high society at the time. He ac cepted the hospitality of a wealthy French financier, Le Ray de Chaumont, and lived at Passy near Paris, in wise obscurity. Ver gennes esteemed him. He went to Versailles regularly and was able to keep in touch with the French administration. He per suaded them to help America financially and materially by send ing foodstuffs, arms and ammunition, and led them into an alli ance which was signed at Versailles in Feb. 1778.' A few weeks later (March 20) he was received by the king and queen who treated him most civilly. But this was not the end of his trou bles. The war was slower, longer and more difficult than the French had expected, and Franklin was obliged to ask constantly for more money. He received from the king and his Government about io million French livres as a gift and 45 million livres in loans, a large sum for the time. He had at the same time to fight English propaganda. To achieve this he gave out many articles and news items, particularly to the curious newspaper Les A f faires de l'Angleterre et de l'Amerique (1776-79), and published several of his famous and successful hoaxes, An Edict of the King of Prussia (1773), Letter of the Count de Schaumberg to the Baron Hohendorf Commanding the Hessian troops in America the fictitious Supplement to the Boston Chronicle (1782), etc. At the same time he wrote and distributed amongst a few chosen friends his charming little pieces called Bagatelles, full of wit, emotion and wisdom. He dedicated some of them to Ma dame Helvetius, the still beautiful widow of the famous philoso pher (whom he had tried to marry), and some to Madame Bril lon, the charming wife of a French financier, who had taken the title and position of "his daughter," but al), these pleasures were disturbed by the sour jealousy of his American colleagues, espe 'To tell the truth the department of foreign affairs in France had been hoping for the American revolution for years, and was very willing to help it.

cially Arthur Lee and John Adams. Both were suspicious of the French and could not agree with Franklin on anything. In 1781 when he was appointed a member of the commission to negotiate a treaty of peace between England and the United States he was overruled by his colleagues, who obliged him to ignore the in structions Congress had given and to negotiate with England without consulting Vergennes. Finally the treaty was signed at Versailles on Sept. 3, 1783. Franklin's last two years in France are really a curious spectacle of a popularity that was almost like an apotheosis. I-Ie was so prominent that the king of France made him one of the commissioners to report on Mesmer and animal magnetism (1784) . His position as one of the highest dignitaries in freemasonry (he was "venerable" of the lodge of the Nine Sis ters—the most intellectual and seemingly the most important in France in 1779-81) put him in contact with all the philosophers and future revolutionaries, and he did much to develop and clarify their ideas. He wished to see France more liberal but was opposed to any violent revolution.

Later Life.

His resignation as minister to France was ac cepted by Congress in 1785 and he returned at once to Philadel phia where he arrived in Sept. after spending a few days on the English coast with old friends and his son, with whom he was reconciled, although his attitude during the war had deeply hurt him.He was elected president of the commonwealth of Pennsyl vania and re-elected thrice. Surrounded by his children (his daughter and his son-in-law, Mr. and Mrs. Bache and their f am ily) he led a happy and busy life, building three houses, trying to finish his autobiography (commenced in England in 1771, con tinued in France in 1784, but brought up only to 1757). In 1787 he was appointed a delegate to the constitutional convention and in it he played an important part. He suggested or advocated only a few of the final articles, but his influence, constantly exerted in favour of co-operation and compromise, contributed strongly to the final agreement. He had not forgotten his old scientific inter ests and published in 1786 Maritime Observations in a letter from Dr. Franklin to Mr. Alphonsus le Roy, in 1787 Observations on the causes and cures of Smoky Chimneys. His unabated zeal for the welfare of mankind led him to publish in the last months of his life several papers on behalf of the abolition of slavery.

But his time had come. The strong body which had withstood so many tests and fights was breaking down. He had been a great sufferer from gallstones for several years and was afflicted also with gout. He was slow to recover from a fall on the stairs. Finally he died in Philadelphia on April 17, 179o, after a short illness. Philadelphia gave him a magnificent funeral. The French assembly went into mourning for three days. The whole civilized world was moved by the disappearance of the old sage who had done so much good during his long life.

His Character and Achievements.

Franklin's achieve ments are so great and so numerous that it is impossible to sum up all of them. We can say, nevertheless, that recent documents disprove most of the accusations which were hurled at him. He did not advise the English Government in favour of the Stamp Act, as many have said ; he did not betray his country in favour of France as Adams thought ; he was not a plotter and a deceitful politician as too many people in England and France have be lieved. The only justifiable reproaches would be that he seems to have been too fond of his family and too eager to work in their behalf and that, when he had a difficult and honest aim, he did not hesitate to use roundabout methods to achieve it. Nobody in the 18th century knew so well as he how to pull the wires of public opinion and make use of newspapers, secret societies, academies and so on. He was one of the broadest as well as one of the most creative minds of his time ; his theory of electricity was not origi nal, but was surprisingly clear and accurate, and the ideas he ex pressed on the Aurora Borealis, the origin of the north-east storms in America, earthquakes and sundry subjects of natural history or mathematics are always precise and interesting even when facts have not confirmed them. The scientists of the 18th century, unable to experiment and too absorbed in logic, admired him for his practical and realistic talents. His medical theories were equally esteemed, and received much recognition, particu larly his theory on the origin of colds.He was less fortunate in politics. He had broad, generous and progressive ideas. His great hope was to see America grow and develop within the British empire and become so strong that it would be ipso facto and without struggle the centre of the em pire, or, at any rate, free. He wished to avoid a bloody revolution, and thought that if the Americans were patient enough they would be sure to win simply by waiting and without using force. But when the war began he showed a splendid spirit of energy. He offered all the money he had to Congress. He gave up all his English affiliations, thoroughly changed his point of view, was strongly in favour of the French alliance, and felt deep gratitude to the French Government.

His economic ideas were not original. He took them at first from the English writers of the mercantile school (mostly Wil liam Petty) and of ter 1766 was much under the influence of the French physiocrats. But he was always clearer, less abstract and more practical than the theorists he followed. In politics he was radical, believing in universal suffrage and preferring one cham ber to the bicameral system. In religion he was a moderate deist, respectful of all religions but more attracted by the moral side of them than by their dogmas. He did not believe in revelation. But this point of view, which seems to have been the typical point of view of the freemasons of his time, at least in England and America, he gradually changed towards the end of his life, under the influence of age and of the sentimental atmosphere which pre vailed in the fashionable circles of France. He spoke more often of Christ and seems to have been nearer to Presbyterianism than bef ore.

As a writer he shows a remarkable logic, elegance and felicity of expression, his style is dignified without being pompous, and precise without being dry or cold. He excels in wit, but is able to express strong feelings. When he gave vent to his indignation against the Government of England in particular, he wrote some forceful pages (Rules for reducing a great Empire to a small one). Nobody could approach him without being charmed by his con versation, his humour, wisdom and kindness. He had been a strong, tall, good looking youth ; he was a large, rather heavy old man but with very keen eyes and great dignity. He had a way of telling stories that delighted all his friends and was well liked by the ladies because he seemed equally to enjoy listening to them. He was certainly ambitious, possibly a little more so than he him self realized, but he was never led by his ambition to dishonesty or baseness. He was thrifty and made good use of the money he earned, but he knew how to be generous and especially in the later period of his life enjoyed helping many people. Other men may have been greater, but very few have been more human.