Electrical Fume Precipitation

FUME PRECIPITATION, ELECTRICAL. The pre cipitation of smoke by electricity was described in 1824 by Hohl f eld, a teacher of mathematics in Leipzig, but only after it was independently rediscovered and critically studied by Sir Oliver Lodge about 1884 did it attract general attention and lead to attempts at industrial applications. At the time, however, these proved unsuccessful due to the lack of modern equipment. It was not until 1906, following experiments at the University of California, that the process was commercially successful.

The first installation was at the Selby Smelting Works, near San Francisco, where it was used for the removal of sulphuric acid mist from about 5,000cu. f t. of gases per minute. By 1910 a plant to remove dry dust and fume from 2 5o,000cu.f t. of gas per min. was built at another smelter, and in 1912 the process was successfully extended to the removal of cement dust at nearly a red heat from I,000,000cu.ft. of gas per min. at the Riverside Portland Cement Company, a mill of 2,5oobbls. daily capacity, in the heart of the Californian orange groves, threatened with legal closure as a nuisance because of the dust emitted.

The method removed 98% of the dust, the daily catch being about zoo tons, and equivalent after 13 years to a fully loaded freight train zoo miles long. Although first applied purely to miti gate nuisances, the demand for the process to-day is primarily based on a greater profit to be derived from the gases cleaned or the material removed. At one time during the World War, the Riverside plant was making even more profit from potash inci dentally recovered in its dust than from its cement.

Research Corporation.

Another circumstance aiding the de velopment through friendly public interest was the creation in 1912, under the auspices of the Smithsonian Institution, of the Research Corp. in New York city, to hold and administer as an endowment for research most of the United States patent rights to the process. The corporation besides supervising construc tion and development of this particular process, also serves in general as a clearing house for information and as an ary and trustee between inventors, the industries and the public.

The Process.

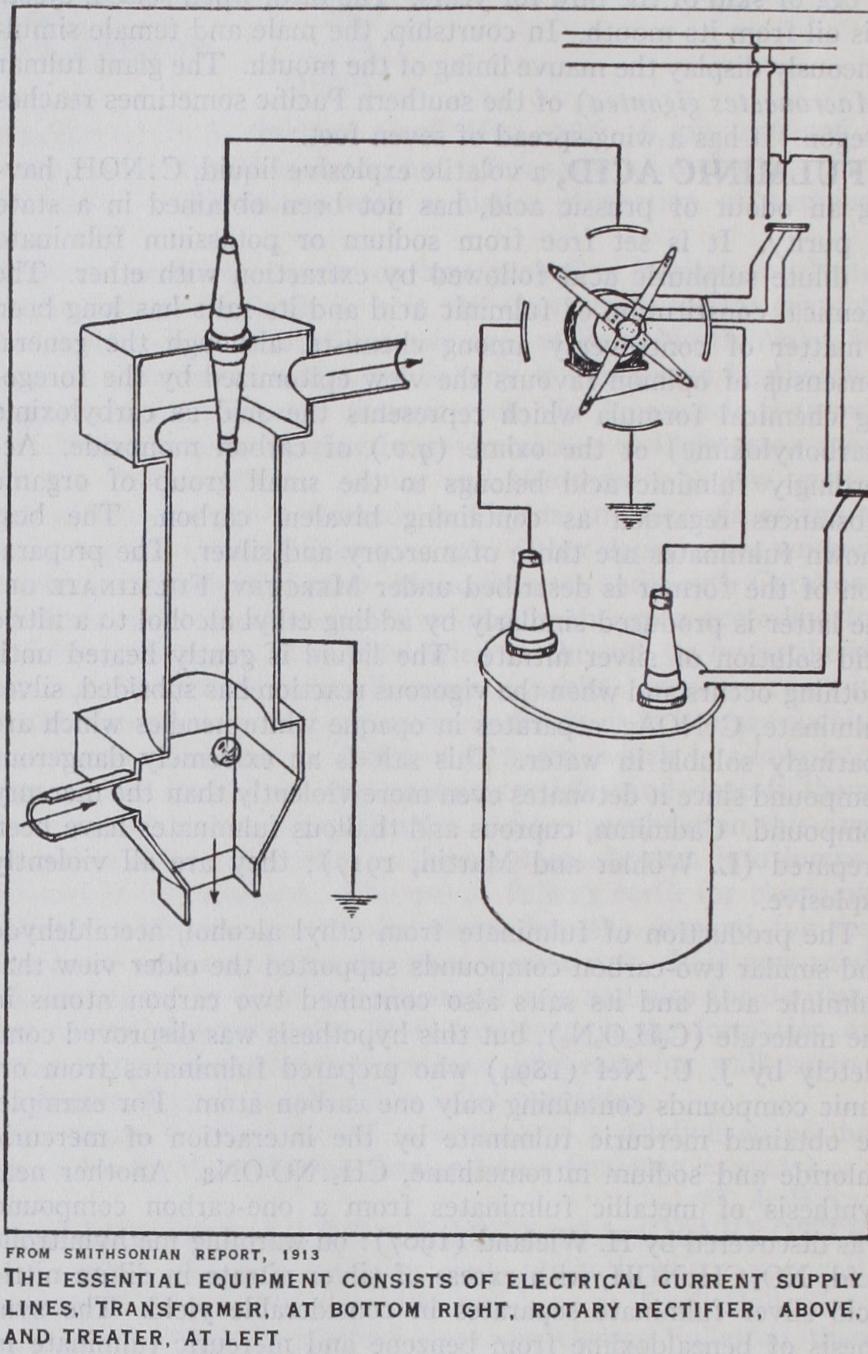

Technically the process consists in securing a uniform, copious but non-disruptive discharge of electricity from small electrode surfaces of one polarity into a stream of cloudy gas. The fine solid or liquid particles composing the dust, fume or smoke are immediately attracted to, and deposited on, large electrode surfaces of opposite polarity, the particles having be come charged from the condensation on their surfaces of a portion of the electricity passing between the electrodes. The process is diagrammatically illustrated here. Alternating current from service lines is stepped up in a transformer to a high voltage and then converted to a direct, or rather a pulsating unidirectional, current by a commutator or "rectifier" driven by a synchronous motor. One side of the line is grounded and connected to a pipe or "treater" carrying the fume-laden gases. This pipe serves as the collecting electrode. The other side of the line terminates in a wire serving as the discharge electrode, which is hung axially within the pipe. Voltage is regulated to secure as strong a glow as corona discharge from the wire electrode as possible without passing over into a disruptive discharge, i.e., a spark or arc. This adjustment is easier when the discharge electrode is the negative, though either polarity may be used.The gas treaters now in general use consist either of a multi plicity of pipes similar to that in the figure, or of plates hung vertically in a flue, the wires being stretched parallel between them. The materials of construction, including the collecting electrodes, vary from iron and lead to reinforced concrete and vitrified earthenware, depending on the composition and tem perature of the gas stream to be treated.

Factors in Design.

Most plants are designed with electrodes of opposite sign 2 to 6in. apart and operating at 30,00o to 8o,000 volts. The size of installation is determined primarily by the volume of gas to be treated and the percentage of suspended mat ter to be removed; the amount, kind and size of particle of the latter being of minor importance. If P is the ratio of out-going to incoming suspended matter, t the average time in seconds that the gas remains between the electrodes, and K, a constant de pending upon the apparatus, voltage, temperature and kind of raw gas, then P=Kt. In most commercial practice t averages about 2 seconds and K varies from 0.2 to 0. 7, the gases travelling from 1 o to 4of t. through the electric field at linear rates of 3 to 15ft. per second. Removal of 90% to 99% of the suspended matter is usually aimed at, and the energy required is i to 3kw. hours per 1 oo,000cu.f t. of gas treated.

Industrial Uses.

The earliest applications of the process were to the smelting and sulphuric acid industries. Installations in such plants in 1026 still outnumbered those in all other indus tries, and amounted to several hundred scattered throughout the world. Equipments at cement mills were fewer in number but handled a large volume of gas and a large tonnage of precipitate. Other important applications are to the detarring of coke-oven gases, the cleaning of producer and iron blast-furnace gas, the cleaning of ventilating air in crushing, grinding and polishing mills (especially where cost of heating in winter makes recircu lation of air important), the recovery of sludge acid fumes in petroleum refineries, the recovery of dust from brown-coal dry ers, and the removal of ash from the stack gases of large power plants burning powdered coal. On a laboratory scale the process has also been applied successfully to sanitary atmospheric analy sis and to gas masks, including the removal of bacteria from air.Anderson, Trans. Amer. Inst. Chem. Eng., vol. xvi., pp. 69-86 (1925), describing theory of comparative effi ciencies of the electrical and other methods; H. J. Bush, Jour. Sac. Chem. Ind. (Lond.) , vol. xli., pp. 22T-28T (1921) , giving history, theory and recent British practice ; F. G. Cottrell, Jour. Ind. and Eng. Chem., vol. iii., pp. (191I) , also Ann. Report, Smith sonian Institution, for 1913, pp. 653-685 (chiefly historical), and Jour. Ind. and Eng. Chem., vol. iv., pp. 864-867 (1912) , on founding of Research Corp.; W. Deutsch, Zeitschrift f. technische Physik, vol. vi., pp. an experimental and detailed theoretical study; D. B. Dow, Bulletin 250, U.S. Bureau of Mines (1926) , on the electrical demulsification of oils ; P. Drinker, M. Thomson and M. Fichet, Jour. Ind. Hygiene, vol. v., pp. 162-185 (1923), application to sanitary analysis of air; R. Durrer, Stahl and Eisen, vol. xxxix., PP. 1,511-18, 1,546-54 (1919), historically very complete and fully illustrated; M. Hohlfeld, Kastner's Archiv f.d. gesamte Naturlehre, vol. ii., pp. 205-206 (1824) , the earliest known reference ; 0. J. Lodge, Jour. Soc. Chem. Ind., vol. v., pp. (1886), the first comprehensive treatment of the subject; A. B. Lamb, G. L. Wendt and R. E. Wilson, Trans. Amer. Electrochem. Soc., vol. xxxv., pp. , application to gas masks and bacteria; R. H. Richards, Text Book of Ore Dressing, pp. 253-255 (1925), on the electrostatic concentration of ores ; W. W. Strong, Chem. and Met. Eng., vol. xvi., pp. 648-652 (1917) , on general theory ; F. Supf and P. H. Prausnitz, Ullmann's Encyclopddie der technischen Chemie, vol. viii. pp. 599-607 (Berlin, 192o), on electrical osmose; H. A. Winne, Gen Elec. Review, vol. xxiv., pp. 910-921 (1921) , a descrip tion and rating of standard equipment. (F. G. C.)