Foundations

FOUNDATIONS, as referred to building and construction, is appropriately applied to all those portions of the structure below the footings of walls, piers and columns. Foundations are designed to transmit the weight of the superstructure to that por tion of the earth's surface on which it rests and which may be called the foundation bed. Foundation beds vary in bearing capacity. All are compressible, hence the erection and loading of any superstructure is accompanied by settlement, though the amount for solid rock is negligible. The object of foundations is to transmit the entire load to the foundation bed at a safe pressure and with small and uniform settlement.

Foundation Beds.

Corresponding geological surface forma tions may show marked local variations, hence, though foundation beds may be scientifically classified, practical experience of a locality often decides the ultimate treatment.Rock.—In some districts massive rock formations may occur near the surface, in others they may be exposed by excavation or otherwise reached. Massive rocks provide good foundation beds. Igneous rocks, dense limestones and sandstones can easily bear pressures of 15 tons per square foot, but on softer rocks the limit may be 8 tons. Many foundation beds are products of rock-dis integration; these include gravel, sand, clay, silt, etc.

Gravel.—Gravel consists of water-worn rock fragments varying much in size. Well-compacted gravel overlying a strong sub stratum, offers a dependable foundation bed which will support at least 4 tons per square foot.

Sand consists of fine rock particles, from 4 in. downwards in diameter. Sand foundations need protection from running water, to prevent lateral escape. Confined sand may support from 2 to 4 tons per square foot.

Clay. This term embraces cohesive soils, in which the char acteristics vary with the composition. Pure clay contributes to plasticity, sand reduces it. Clay becomes plastic with moisture and changes in volume with plasticity; the moisture-content of clay should, therefore, be kept low and uniform ; actual contact with water is to be avoided. Drainage of and diversion of water from the site are the usual precautions. Clay foundations need protection from seasonal variations of temperature and humidity; otherwise changes in volume may lead to structural fractures. Such foundations should be 3 to 4 ft. below ground. Bearing pressures on dry yellow clays are usually limited to 2 tons per square foot and on blue clays to 4 tons per square foot.

Made or Filled Ground; Silt.—Depressions and excavations are often filled artificially. "Filled" ground continues to consolidate over many years. Building over such ground requires excavation or penetration of the filling to a solid bed, and sites with a soft overlying bed may be similarly treated. On low-lying soft ground, buildings may be "floated" on "rafts," i.e., timber or reinforced concrete slabs continuous over the site. Settlement is thus controlled and rendered uniform.

Other foundation beds may be mixtures of materials and will possess intermediate characteristics.

Protection of Foundation Beds.

Lateral support and pro tection are often required. Friable earths crumble on upright faces and soft rocks disintegrate. These may be protected by retention walls. Underlying streams of water should be enclosed in a culvert. Where "ground water" is freely rising and falling basements should be constructed as watertight tanks to resist external hydrostatic pressure and prevent the incursion of water.Bearing Capacity.—Bef ore planning the foundations of an im portant building an investigation of the site is usually necessary; experience of adjacent sites will assist the investigation. If exami nation of the underlying strata is found necessary a trial pit would be sunk, or "boring" adopted, and samples of the strata raised to the surface and examined.

Allowable bearing capacities for foundation beds in any one locality are often scheduled as in the London Steel Framed Build ings Act of 1909. Many American building codes include similar schedules. In doubtful cases experiments may have to be em ployed to determine the bearing capacity.

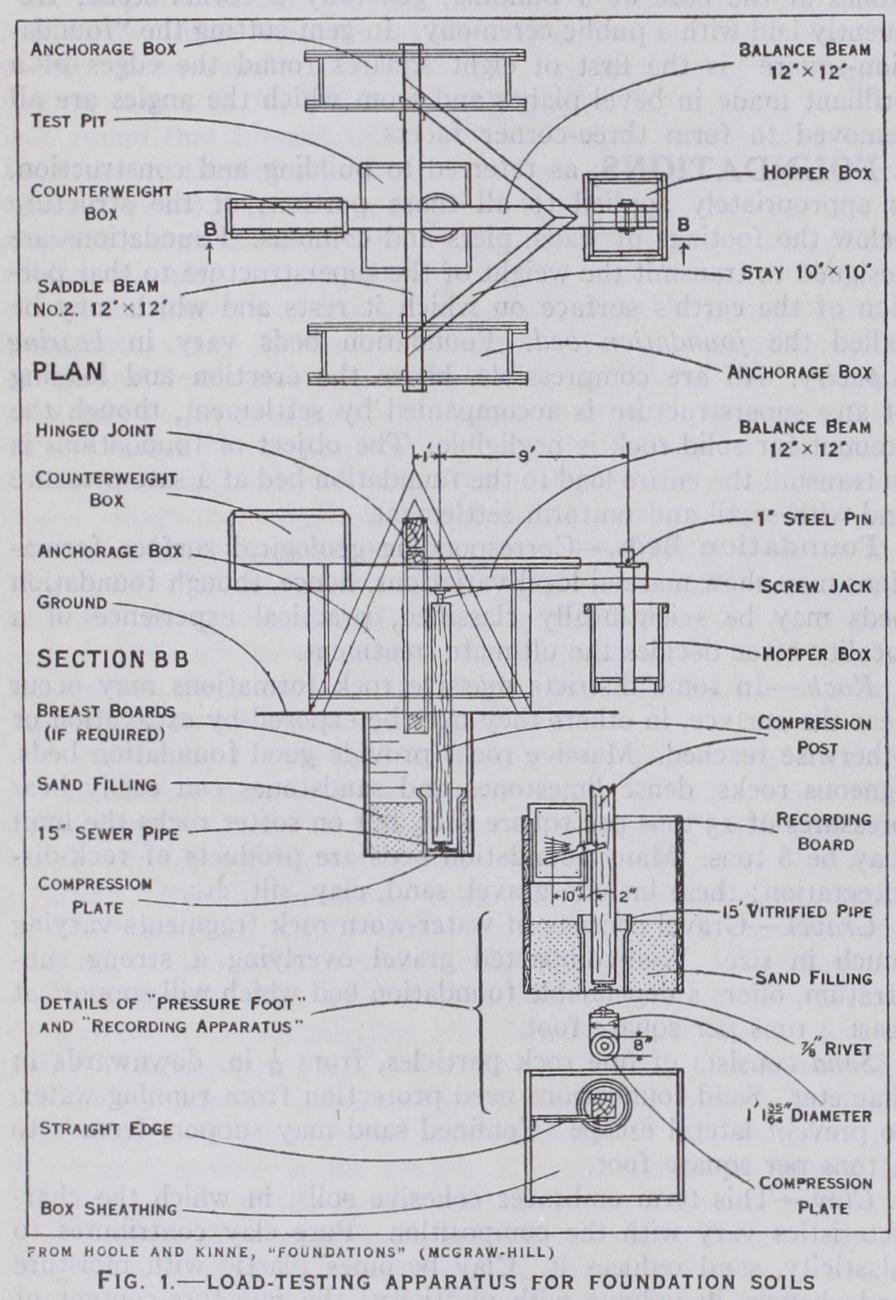

British regulations do not impose bearing tests, but the Building Code of New York City details a test to be conducted on a mini mum area of 4 sq.ft. and after four days 5o% more pressure than the proposed bearing capacity must not produce settlement. Fig. 1 shows the apparatus designed for this test by the American Society of Civil Engineers.

Loads Carried.—The constant load is the weight of the struc ture: its magnitude and distribution are readily determinable.

The movable load fluctuates with occupancy and use, with wind-pressure and snow, and varies from zero to a maximum value. It is difficult to estimate designing loads on foundations but usually when the movable load forms a substantial part of the possible foundation load, the foundations may be designed to carry about 6o% of the sum of the loads for which the structural units have been designed. This percentage is specified, with qual ifications, for certain types of American buildings.

Types of Foundations.— There are two general classes : (a) spread foundations, constructed near the surface and having a base area proportional to the load; and (b) deep foundations, excavated or driven to consider able depth, the horizontal area occupied having little relation to the load carried. Cement con crete (see CONCRETE) is used almost universally for founda tions. It is strong and conforms to the inaccuracies of the founda tion bed.

Grillage Foundations.—Projec tions in foundation concrete may be reinforced with steel, the thickness being then reduced ; or steel may be employed as the principal material. In the latter type, steel beams are used to form a "grillage" in two or more tiers. The load is transmitted through a steel or cast iron base to the tiers of the beams, which are bound together transversely by steel sections or by metal packings and bolts.

The foundation steelwork is bedded upon and encased in con crete.

Reinforced Concrete Foundations.—A foundation having the same function as the steel grillage is also shown in fig. 2. Rein forced concrete is employed (see REINFORCED CONCRETE).

Cantilevered Foundations.—When a large pillar occurs at a boundary adjoining an existing building, and an ordinary founda tion is impossible, an external pillar is linked with an internal one by a heavy beam, having one end projecting as a cantilever. The outer foundation is well within the boundary. Load from the external pillar is transferred to the cantilever, which bears on the foundation and is balanced by the load on the internal pillar. The foundation is designed to exert uniform pressure on the bed when fully loaded.

In

another method two pillars may have a common foundation. The base may be parallel or trapezoidal, and so arranged that the resultant of the two loads lies over the centre of gravity of the base. The trapezoidal base is more suitable for reinforced concrete construction. (See also STRUCTURAL ENGINEERING.) Stepped Foundations.—Changes in foundation level should be made in small "steps" to avoid (a) the diagonal shearing of the foundation bed between levels; and (b) fracture at the vertical junction of the higher and lower sections. The concrete bed should be stepped and made continuous by vertical "ramps." Deep Foundations.—Extensive foundation beds, otherwise good, may reveal soft pockets, which can be bridged over by beams or arches. Foundations on soft strata or filled material may be supported on brick or concrete piers erected in deep excavations, on a firm bed. The piers are connected by arches or beams.Pile Foundations.—A stout pillar of any material driven into the ground is known as a pile. It is generally more economical to use piles than piers, and they may be of round timber, or of square timber shod and banded with iron. Piles may be driven by mechanical devices worked either by man or steam Dower. Steam hammers for rapid driving, give light and quick blows, so reducing damage to the head of the pile. Piles are conveniently grouped to support concentrated loads as at bridge abutments, or under columns in a building. They may be driven until either (a) their points are embedded in a firm substratum (bearing piles), or (b) the friction on their sides is sufficient to provide resistance (fric tion piles) . To distribute the load, timber frames or masses of concrete are laid on the piles.

Concrete Piles.—Concrete piles are mainly of two kinds, viz. (a) pre-cast and (b) cast in-situ. The former have vertical steel bars, bent in at the point, hooped transversely and diagonally and enveloped in concrete. Reinforcement adds to the compressional strength and provides resistance to end blows and to possible side bending when driving. The points are shod with steel or cast iron. Modern rapid-hardening cement permits of moulding and driving in a few days. The "cast in-situ" piles have marked advantages over those pre-cast ; space for moulding is not required, work is rapid and piles can be loaded soon of ter driving. This type may be classified into (a) systems in which a tapered tube is driven, withdrawn, and the space filled with concrete, or in which a man drel and sheath are driven, the mandrel being withdrawn and the sheath left and filled with concrete; (b) systems in which a par allel tube, shod with solid metal, is driven, the tube being grad ually withdrawn and concrete poured to fill the hole and enclos ing a frame of reinforcement if desired ; (c) systems designed for enlarged bases to increase the load capacity; and (d) systems in which tubes are sunk into the ground, the earth withdrawn from the inside, and the tubes filled with concrete. In one patent form, the tube employed is vibrated on withdrawal to assist the consoli dation of the concrete.

The supporting power of piles is a difficult and controversial subject and cannot be included here.

Special Foundations.

Exceptional forms of foundation occur in large and heavy structures, bridge piers, dock walls and harbour work, in which large excavations may cover an entire building site. The vertical sides of the cutting must usually be maintained by temporary supports provided by shoring (see SHORING) .Deep Foundations for Piers.—Timber is usually employed to strut the sides of deep excavations for piers, the timber being inserted in short stages. In the U.S.A. a circular excavation is often made and the sides supported by short vertical poling boards wedged against cast iron circular frames.

The Open Caisson.—Danger to property may occur if adjacent excavations cause withdrawal of running sand, hence for excava tions through wet strata, water and fine sand must be kept out of the cutting. In vertical shafts the sides may be supported by steel or concrete linings added in short lengths at the top, as the excavation proceeds. An enlarged base is usually formed to increase the bearing area; and the lining is filled with concrete upon which the surface foundation is laid.

The Pneumatic Caisson.—For preventing the incursion of wa ter to excavations in wet strata and in river beds, the pneumatic caisson is employed, this being a cylinder of steel or reinforced concrete of the same size as the foundation. The caisson is a rigid casing without base and having cutting edges. Units are added above water level as the caisson sinks. A working chamber is formed in the base, isolated by an "air-lock." The men work in compressed air, which must resist the incursion of water. To admit and withdraw men and materials the air-lock chamber has two doors at different levels. The air pressure is maintained by re-sealing one door before opening the other; at the required depth the space of the working chamber is sealed with concrete. Steel caissons are usually filled or lined with concrete, and rein forced concrete shells are bridged over to receive the super structure.

Sheet Piling.—One function of sheet piling is to support later ally foundation beds which would spread under pressure ; sites are occasionally surrounded by sheet piling. It also gives con tinuous support to very soft ground, as in water-bearing strata, where shallow excavations and conditions do not make a closed caisson imperative. For much ordinary work timber sheet piles are used, driven between horizontal walings secured to square guide piles. Sheet piles formed by special sections of rolled steel are in common use, and various forms of reinforced concrete sheet pile are also employed.

A patented type of reinforced square pile has two wings. Driven edge to edge these piles may be used as sheeting or for retaining "made" earth, assisted by reinforced ties anchored to the earth behind the wall. The piles are designed to resist the consequent bending moments. Sheet piles have the feet splayed to induce the entering pile to close against the edge of its neighbour.

The Coffer Dam is a substantial temporary dam, used where the hydrostatic head is considerable and simple sheet piling is inadequate. A coffer dam may surround an enclosure for the removal of water and soil and the insertion of a foundation or, for quay walls, may be on the water side only. In modern practice two rows of close piling are used, 5 ft. and upwards apart, driven to impervious ground. The space within the piles is cleared and filled with puddled clay. On completion the water is pumped from the enclosure and excavation or construction may proceed. For deep interior excavation after withdrawal of water the coffer dam is supported by transverse strutting or by inclined shoring.