France in the World War

FRANCE IN THE WORLD WAR In face of Germany's continual increases in the man-power and material strength of her armies, the French Parliament decided in 1913 to return to the Three-Year Act, the classes to be embodied at the age of 20, so that the 1912 and 1913 classes could be called up simultaneously in October and November 1913. A special appropriation of Soo millions was also voted for military equip ment. Unfortunately the full effect of these measures could not make itself felt until 1916. The three tables which follow illustrate: the growth of the eff ectives ; the growth of the budgets; the mili tary position of the two countries in 1914. They bring out clearly the considerable increase in Germany's armaments, and France's reluctance to join in a race in which, indeed, she remained always far behind. They also demonstrate the French army's inferiority in heavy artillery and special troops.

Growth of the Budgets of the French and German T'Var Ministries Before the War Daily Output of Certain Munitions Scheduled output in mobilization orders Maximum attained 14,000 75-mm. shells 226,000 75-mm. shells (1917) ,, 51,78o 155-mm. ,, 2,600,000 rifle cartridges 7,000,000 rifle cartridges (1917) (C) Railways.—From the beginning to end of the war a heavy call was made on the French railways. The traffic was on an average 40% greater than in 1913, and at certain periods, in the uninvaded part of the North, i00% greater. At the outset, mobil isation movements demanded zo,000 trains, and subsequently cov ering and concentration movements called for 5,400. During the operations about 1o0,000 trains were run from point to point on the front, conveying 6o million men with the corresponding stores. Supplies of all kinds for the forces required an average of 200 trains a day. Additional to all this traffic was that due to the evacuation of the civilian population of the invaded regions, the supply of the civilian population, the provisioning of factories with raw materials, etc. Further, in the course of four years the railway engineer troops constructed a length of track (7,500 kilo metres) equal to one-sixth of the entire French railway system.

(D) Ports. The following figures represent goods loaded and unloaded : 1913, 42,300,000 tons; 1916, 56,673,00o tons; 1918, 53,550,000 tons.

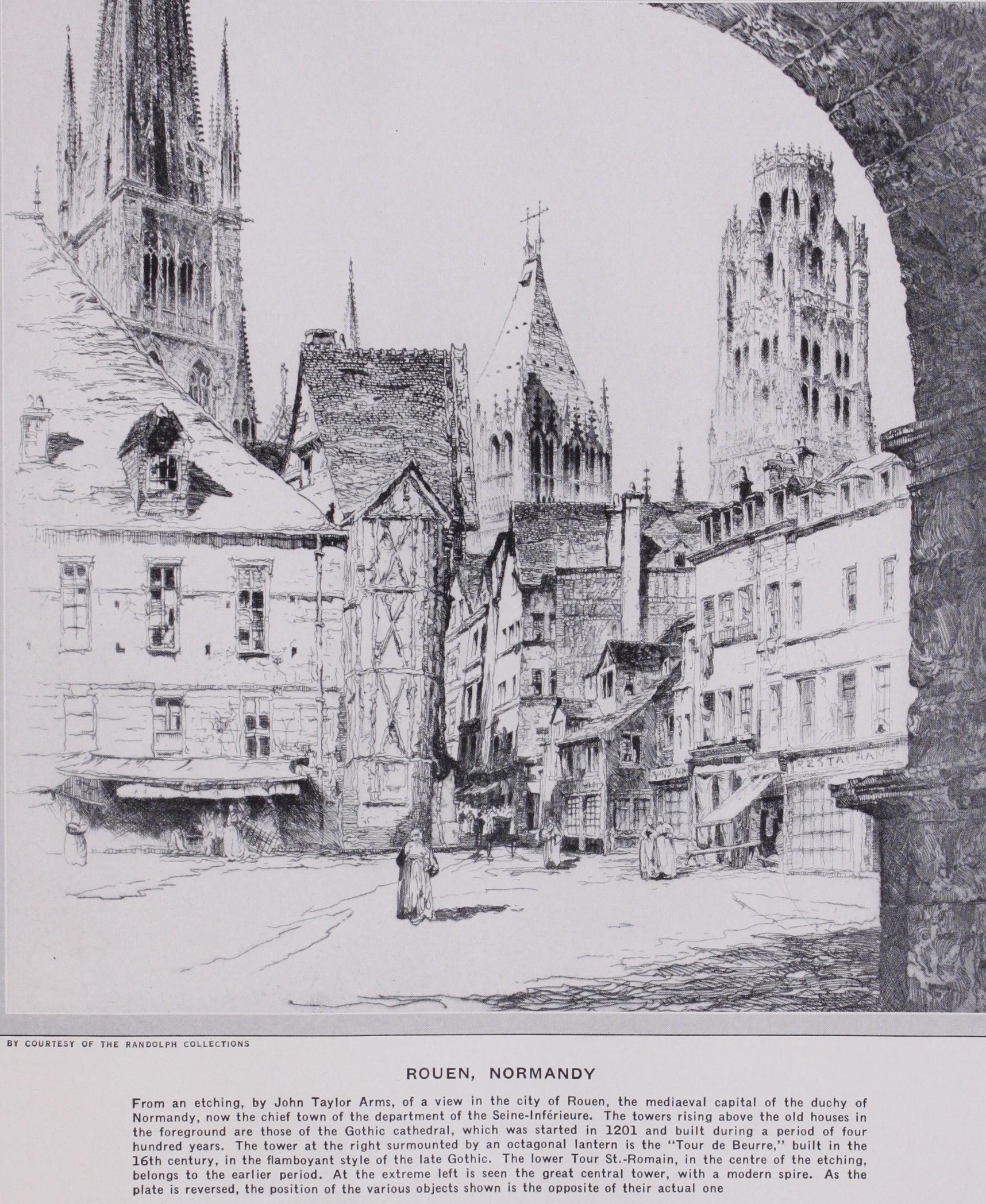

At Rouen, where 5,148,0oo tons were discharged in 1913, the figure for 1918 was z o,000,000. The import traffic of Le Havre rose from 2,747,000 tons in 1913 to in 1918.

Post-war national defence in France has reached the final stage of its development. The essential legislation is, without neglecting the lessons of the war, to reduce the burden imposed on the coun try to a minimum. The war left France impoverished in man power (1,700,000 killed and 600,000 disabled) and also economi cally and financially. But, deprived of the treaties of assistance contemplated in 1919, and not feeling that her late enemies shared her own pacific spirit, she was obliged to retain the ability to provide for her security unaided.

Such were the principles, in some senses opposite, which under lay the reforms effected in the military organization. They led to the following conclusions: that in time of peace France should possess only such military and naval forces as were indispensable : (I) to cover the mobilisation of the nation in case of attack and enable it to be carried out fast enough to cope with the rapidity of such attack, (2) to provide for the security of her colonies and her communications with her oversea possessions in case of need, (3) to enforce the treaties of peace in concert with her allies; and that the general organisation of the nation for war should be pre pared in every detail. In consequence, compulsory personal serv ice was maintained, but the period was reduced to one year (Act of March 31, 1928) . The i8-months' period of military service will be maintained until Nov. 1, 193o, when it is expected that the necessary conditions for the reduction of the period of service with the colours (recruiting of additional professional soldiers, military police and civilian employees; formation of a mobile National Guard) will have been fulfilled. The tables which follow show the effectives for January 1, 1928, as compared with those for August I, 1914.

General Organisation of National Defence.

The last war taught the lesson that the nation as a whole must be organised for the eventuality of war, so that all may be in readiness beforehand for the entire strength of the country, civil and military, and the whole of its economic, industrial and other resources, to be thrown into the scale. A bill for the organisation of the nation to meet the contingency of war has accordingly been introduced by the Gov ernment, passed by the Chamber, and adopted with certain amend ments by the Senate, and now only awaits its formal enactment by both Houses. The following are its main features : (a) Functions of the Government.—The Government is respon sible for preparing the organisation of the country to meet the con tingency of war. It will be assisted by the Supreme Council for National Defence, whose subordinate bodies (Commission of Enquiry and Permanent General Secretariat) are responsible for investigation and for co-ordination between Ministries.The direction of the war will be in the hands of the Government, which will decide the ultimate objectives of the operations, dis tribute the forces among the different theatres of war, and super vise their employment ; the actual conduct of operations, however, will be entrusted unconditionally to the commanders-in-chief of the army and navy. The Government will determine the duties of each Ministerial Department in time of war. Each Minister will be held responsible for the preparation and execution of the work of his department.

(b) Decentralisation of Preparations.—The preparations for or ganising the nation for war form too complicated a task to be car ried out by the unaided efforts of the Central Offices of the Ministries. The work has been decentralised and given to the local departments. The Prefect of each department is made responsible for co-ordinating the preparatory work to be done by all officials in his area. He is assisted by an advisory committee of the repre sentatives of the various Ministries in the department, together with employers' and workers' delegates. Apart from persons liable for military service, all men over 18 years of age are bound to take a share in national defence proportionate to their physical and mental capacities.

(c) Economic Organisation.—A single Minister is responsible for the production and collection of a single commodity, and on mobil isation must be in a position to supply all the Ministries requiring that commodity. The supplying Ministries place orders with man ufacturers for the commodities for which they are responsible. As one firm may manufacture goods required by several supplying Ministries, the economic allotment of output demands that a single branch should be entrusted with the negotiations with any particular firm, and should arrange the placing of orders. This co-ordination is effected by the Inspectorate General of Munitions on mobilisation, by means of machinery specially created for the purpose.

The army, when mobilised, consists principally of the reserves called up. The standing army is only its nucleus, and its duties are to train the contingents called up, to guard the oversea posses sions, to prepare for mobilisation, and, in the event of an attack, to cover the frontier until mobilisation is completed.

The Recruitment Act of March 3r, 1928 provides fora—(i.) Men with the colours, comprising: (a) men called up for one year (all who have attained their 21st year) ; (b) half the contingent is called up on April 15 and the other half on Oct. 15. Volunteers (enlisted, re-enlisted, and officers) constituting the cadres of pro fessional officers and N.C.O.'s required in peace and war. (ii.) Men on long furlough (disponibilite), which lasts for three years after the completion of service with the colours; these men may be called up in case of need. (iii.) A first reserve, also to be used on active service, in which the citizen serves 16 years ; and a sec ond reserve in which he serves for 8 years; this reserve is to be employed on home military service or in administrative and eco nomic organising work.

The 635,000 rank and file (France, occupied areas, and colonies) at present forming the Army are made up as follows:— Frenchmen (5', contingents called up, and professional soldiers) . . 383,000 Foreigners (Foreign Legion) . . . . . . . 56,50o North African native troops . . . . 503,500 Colonial native troops . . . . . . . 87,500 Irregular and auxiliary native troops . . . . . 52,500 Gendarmerie and National Guard . . . . . . 32,000 Total . . 63 5,000 Army Organisation.—The Act of March 28, 1928, dealing with the constitution of cadres and effectives provides for the distribution of the effectives among the various arms and services. When this Act comes into full operation (during 1928), the army will comprise 25 infantry and 5 cavalry divisions. The standing army is divided into three'classes, embodying home and colonial troops. (a) Home forces, composed as a rule of French troops and stationed permanently in France. (b) Oversea forces, composed of Frenchmen, natives, and foreigners, detailed to occupy and defend French possessions, and stationed permanently there. (c) Mobile forces, reserves for the permanent oversea forces, consisting of French and native troops, and normally stationed in France and North Africa. The peace establishment (including officers) of these forces is approximately as follows : Home forces . . 365,000 Oversea forces . . . . . . . . . 230,000 Mobile forces . . . . . . . . . Distribution of Troops.—The following table shows the propor tions of the different arms at mobilisation in 1914, at the armistice, and at the present time.

This table illustrates the development of the primarily mechan ised arms (tank corps, artillery) at the expense of the non mechanised arms (cavalry). The movement would be still more accentuated but for the necessity of increasing the normal rate of embodiment in certain arms requiring young men (cavalry, air force) because their peace establishment has to be kept at a figure approaching their war strength.

Officers.—The system of military training embraces both offi cers on the active list and officers of the reserve.

The military training of officers on the active list is based on the following principles :—Military training should be founded on a wide general education with a strong scientific bias, and on a spe cialized technical education for each arm. The officer's military education should be perfected during his service by keeping him abreast of developments in military manoeuvre, tactics and tech nique. Advanced training should be provided for staff officers and those who are fit for promotion to field rank.

Primary military training is given at the officer cadet schools (Saint-Cyr, the Polytechnique, and the Army Medical Service School), to which admission is obtained by competitive examina tion open to young men not yet liable for military service ; and at the officer cadet schools for N.C.O.'s (St.-Maixent, Saumur, Poitiers, Versailles), which are filled by competitive examination among professional non-commissioned officers. The general train ing is completed in detail for each arm at the appropriate special school.

Additional training is provided by sending officers at various stages of their career to the schools for special branches or to technical courses (practical musketry courses, school of liaison and signalling, etc.), and to the special schools for the different arms (promotion courses, general course for field officers, instruc tional tours for colonels and general officers).

Prospective staff officers receive advanced training at the Staff College. Training for high command is given at the advanced military training centre and at the artillery tactical training centre. Officers of the reserve receive, as far as possible, the same military training as officers on the active list, and at the same schools (St.-Cyr, St.-Maixent, Saumur, Poitiers, Versailles, Vin cennes). The courses, however, are shorter. On embodiment, pros pective reserve officers first perform six months' service with the colours; they then (after competitive examination) attend the reserve officer cadet schools, and, if they pass the final examina tion, perform their last month of service as second lieutenants of reserve. Students in important educational establishments (facul ties, institutes, technical schools, etc.) take preliminary military courses there; then, after examination, they pass direct into the reserve officer cadet schools, and perform their last six months of service as officers. Reserve officers receive additional military instruction during their training periods, and at refresher courses when not on service.

N.C.O.'s and Men.—The N.C.O.'s comprise professional N.C.O.'s, and corporals and lance-corporals of the contingent. Both classes are trained in platoons organised for the purpose in the regiments, and receive additional instruction at training cen tres. The training of the rank and file begins with physical train ing before embodiment, continues throughout the period of serv ice with the colours, and is resumed when they are called up for periods of training as reservists.

Tactical training of cadres and units begins as soon as indi vidual instruction ends, and reaches its height in camp. Sufficient numbers are obtained with the help of the reservists who are called up at the same times. This training comprises separate exercises for each arm (the artillery, in particular, does its firing practice), and combined exercises.

A country's theory of war is not now, as it may once have been, a purely military concept. It is essentially a reflexion of the political principles that country pursues. Although forced by ex perience to maintain a certain attitude of mistrust, France regards herself as being better protected now than she was in 1914, thanks to the undertakings given at Versailles, to the Covenant of the League of Nations, and to the Locarno agreements. Following out this purely defensive theory, she has abandoned the idea of a powerful peace-time army, easily convertible into an attacking machine, and always supplied with all the weapons of offence necessary to the conduct of a war with large forces rapidly mobilised. Instead, she has unreservedly adopted the theory of the "nation in arms," taking the view that in the event of an attack the entire country should be responsible for its own defence, and that the peace-time army should only be expected to cover the frontiers while the nation prepares itself to defend its territory.

According to this theory of war, the French High Command is bound to take all necessary steps in advance to enable the peace time army, though reduced to the minimum strength, to discharge its function of providing a screen if required. For this purpose the frontier fortifications need to be strengthened. Further, the High Command proposes to equip the regular army with every device that will increase the efficacy of its fire to the maximum (auto matic weapons, observation and signalling arrangements, etc.). It is endeavouring to provide sufficient transport (railways, motor vehicles) to enable the reserves to be speedily conveyed to threat ened points. It is also seeking to establish mechanised formations (major units, artillery reserves) and air forces which will be able to act with the minimum of delay.

The present military organisation of the French Army and its training are based strictly on these principles : (r) The period of service is reduced to the minimum compatible with the provision of adequate cover 08 months at present ; one year from 193o, when the necessary conditions will be satisfied). (2) The regular army is to provide a screen and to serve as a training school for the reserve formations, which will make up the real war-time army. Moreover, a considerable portion of its establishment is em ployed outside France for the purpose of maintaining French authority, if necessary, in the oversea territories. (3) The reserve formations which make up the army must be strongly officered and thoroughly trained. These two requirements entail: (a) an in crease in the number of professional N.C.O.'s, many of whom will form the nucleus of the subaltern cadres of the reserve units ; (b) the training and periodical additional training of reserve officers, as already described; (c) the calling of reservists to the colours for short but frequent periods, such reservists to be detailed where possible to the units in which they served when in the first line, or to corps having some degree of connection with those units ; (d) the training of reservists in camp, in contact with men serving with the colours, and under the direction of officers on the active list.

A policy has also been taken up with regard to arms and equip ment : (a) new automatic weapons, representing an improvement on those used by the French infantry during the war, have been brought into service. (b) Owing to lack of funds, the other arms are for the most part keeping their old material, but are being in creasingly mechanised. (c) The liaison and signalling arrange ments in use during the war are being daily improved to keep pace with scientific developments. (d) The Air Force is being exercised in close mutual communication between machines in flight and : Army headquarters, other arms, troops in the field, aircraft and Air Force headquarters on the ground. It is being exercised also in forming immediate temporary concentrations to act against important points without losing its readiness for every eventuality, and is thus becoming a first-rate covering arm and supplementing the action of the other arms.

Lastly, in order that those citizens who will form the mobilised army in time of war may be quickly furnished with arms, ammuni tion and other necessaries not normally available, provision is already being made in peace-time for a detailed organisation to effect, when need arises, the industrial mobilisation of the nation— the more specifically military part of its organisation for the contingency of war. (B. SE.) The geographical position of France has always compelled her to draw her navy from and maintain it in two widely different areas : the Channel and the Atlantic coast on the north and west, and the Mediterranean in the South. Originally the rule of the French Monarchy was only effective in the centre of the country, and before France could begin to acquire sea power it was neces sary for her authority to be extended to the coasts. A beginning was made in this direction in 1180-1223, when Philip Augustus expelled King John of England from Normandy and Poitou. Although the process was not complete until Louis XII. (1498 1515), a Royal fleet was in being as early as 1249, when Louis IX. sailed on his first crusade. This monarch also established the first French dockyard at Aiguesmortes, while he also created the first admirals appointed by the French Crown, Ugo Lercari and di Levante, both Genoese. Later Aiguesmortes was cut off from the sea by the encroachment of the land and Narbonne and Marseilles became the war ports.

The fleet of Louis IX. was purely Mediterranean in character. It consisted of galleys with secondary sail power, but mainly de pendent on oars. The rowers of the French galleys were originally hired men, but by the middle of the 15th century they began to be composed of galley slaves—prisoners of war, slaves purchased in Africa, criminals or vagabonds serving their sentences. Under Philip IV., le Bel (1285-1314), efforts were made to constitute a naval force in the Channel in rivalry to Edward I. of England. As before, the Genoese were called in to assist and build a dock yard at Rouen.

The fortunes of the French navy have been wont to suffer from alternations of attention and neglect. Francis I. made vigorous efforts to revive it at the very close of his reign but it languished again until the 17th century. Richelieu, the great minister of Louis XIII. found the navy extinct. He was reduced to seeking the help of English ships against the Huguenots, but from him dates the creation of a better fleet. In 1626 he abolished the office of Admiral of France, created by Louis IX., and himself assumed the title of Grand Maitre et Surintendant de la Naviga tion, while seagoing commands were entrusted to two Admirals, one assigned to the west or Atlantic and Channel, the other to the Mediterranean. Richelieu's establishment shrivelled after his death and was recreated by Louis XIV. (1643-1714). A code of laws was then framed bringing in compulsory service, affecting the inhabitants of the coast and of river valleys, and at the same time a system was organised for the control of finances and of the dockyards of Toulon, Brest and Rochefort, while the office of Admiral of France was recreated.

As the result of these efforts the organisation of the French Royal navy on paper appeared very complete, but in practice it was not efficient. The Admiral of France was Louis' natural son, the duc de Vermondois, while the fleet was officered by men who owed more to birth than to professional ability. The ships' com panies were ill-paid, ill-fed and otherwise defrauded and the severity of the Inscription Maritime was most unpopular. Under Louis XVI. (1774-1792) when the Revolution broke out, the majority of the noble officers were massacred by the Jacobins or driven into exile. It was long before the Republic was able to create an effective navy and to form a new body of educated officers, but France had no reason to be ashamed of the way her fleet fought at Trafalgar, in ; but that battle marked her end as a naval power capable of challenging Britain by sea and, with the introduction of steam and ironclads, she ceased to maintain a fleet which constituted a menace to her traditional enemy across the Channel. From time to time some temporary irritant, such as the Fashoda incident in 1897, called forth comparisons between the British and French fleets, while the development of the tor pedo boat, to which France paid much attention in the 'seventies, was regarded by many people at the time as an attempt to neu tralize the power of the British battlefleet, but the World War found the two navies united in a common cause.

Between 1908 and the World War, France exerted herself to improve her fleet. From 5905 to 1909 inclusive, Germany had spent an annual average of 377 million gold francs on her fleet, while France had spent only 318 millions. A more serious differ ence was that Germany had a modern fleet, of which more than one-fourth of the units were nearly new. France, on the other hand, had a fleet mainly consisting of vessels approaching obsoles cence. This resulted in considerable annual expenditure in upkeep and less to spare for new construction. By 1909 the tonnage of the German fleet (689,00o tons) exceeded that of the French fleet (664,000 tons) ; and for an equal tonnage France could only meet Germany's new units with old, and in some cases obsolete, vessels.

In 191o, the latest battleships France possessed were the six ships of the "Voltaire" type, then nearing completion. These were similar to the British "Lord Nelson" (1906). The most modern battleships of the French Navy in commission were the two "Republiques" and four "Justices"—approximately equival ent to the British "Londons" (1902), the German "Braunsch weigs" (1902), and the American "New Jerseys" (1904). More over, while Germany had increased the number and improved the type of her light cruisers, which constituted so strong a threat to communications, France had devoted most of her attention to the construction of armoured cruisers of from 12,000 to 14,000 tons. These were not strong enough to act as battle-cruisers, and not fast enough to outpace the light cruisers. Again, the French torpedo-boats, whether of 35o tons ("Poignard" type) or of ("Spahi" type), had no longer the speed, endurance and armament necessary for an equal contest with the big German torpedo-boats. During the next four years great efforts were made to improve the position, but Germany had too long a lead for the situation to be retrieved in the time.

Dreadnoughts were put on the stocks—four "Courbets" (23,000 tons; 12 305-mm. guns), which, however, were barely ready in 1914; three "Provences" (23,50o tons; 10 34o-mm. guns) were launched in 1913, but could not be put into commission until long after the opening of hostilities. In 1914 other battleships were building or in contemplation, but they could not be completed or begun owing to war necessities. Bigger torpedo-boats (80o tons), very fast and well armed for that time, were also built. These vessels, of the "Bouclier" type, were to render valuable service in the war, which threw such heavy work on the lighter craft. There were far from enough of them to do what was needed. As regards submarines, France continued to construct and improve the "Laubeuf" type. Submarines of 800-ton were on the stocks in 1914; but it was then so difficult in France to obtain and install Diesel engines of sufficient power that these vessels could not be put into commission for some time, and after a number of trials they were ultimately equipped with steam power.

Simultaneously with this strengthening of the material side of the navy, training was improved and, most important of all, the French naval forces were redistributed, the main squadrons being concentrated in the Mediterranean.