Friendly Societies

FRIENDLY SOCIETIES. A friendly society is a mutual association the chief purpose of which is to provide its members with money allowances during incapacity for work resulting from sickness or infirmity and to make a provision for the immediate necessities arising on the death of a member or his wife. This definition is not exhaustive since there exist a considerable number of societies (some of them very large) the objects of which are principally restricted to the insurance of small sums at death. These bodies customarily use the words "friendly society" in their title and are registered in Great Britain under the Friendly Societies Act. To that extent they come within the scope of the present article but the great majority of them are, in fact, engaged in the business of industrial assurance and are fully described under that heading. Their methods of operation and their sub jection to the statute by which industrial assurance is regulated (Industrial Assurance Act, 1923) distinguish them from the ordi nary friendly society, and no further reference will be made to them in dealing with this subject.

The functions of most of the British friendly societies have undergone some change since 1912 when they became associated with the administration of national health insurance. The present article deals wholly with the position and activities of the soci eties as instruments of voluntary insurance, but in order to appre ciate the scope of the societies' work it should be understood that a friendly society may be an "approved society" under the National Health Insurance Act and at the same time may be a wholly voluntary institution conducting its operations in this aspect under the sanction of the Friendly Societies Act or (if it is unregistered) of common law, without oversight by the govern ment departments to which it is responsible so far as concerns its functions in regard to health insurance. If a society is so con stituted it has separate codes of rules for each side of its business; in the usual case a majority of the members will be insured in respect of both voluntary and statutory benefits, but some will be insured for the "State" benefits only, while others will be insured on the voluntary side alone, these latter consisting partly of tradesmen and others not employed within the meaning of the National Health Insurance Act and partly of members who come within the Act but have effected their insurances under it else where.

The Friendly Societies Act, 1896. as amended by the Act of 1 qo8, defines a friendly society as a society "for the purpose of providing by voluntary subscriptions of the members thereof, with or without the aid of donations, for "(a) The relief or maintenance of the members, their hus bands, wives, children, fathers, mothers, brothers or sisters, nephews or nieces, or wards being orphans, during sickness or other infirmity, whether bodily or mental, in old age (which shall mean any age after 5o) or in widowhood, or for the relief or maintenance of the orphan children of members during mi nority ; or "(b) Insuring money to be paid on the birth of a member's child or on the death of a member, or for the funeral expenses of the husband, wife, or child of a member, or of the widow of a deceased member, or, as respects persons of the Jewish persua sion, for the payment of a sum of money during the period of con fined mourning ; or "(c) The relief or maintenance of the members when on travel in search of employment, or when in distressed circum stances, or in case of shipwreck or loss or damage of or to boats or nets; or "(d) The endowment of members or nominees of members at any age; or "(e) The insurance against fire, to any amount not exceeding 115, of the tools or implements of the trade or calling of the members ; or "(f) Guaranteeing the performance of their duties by officers and servants of the society or any branch thereof." The great majority of the societies limit their operations to the objects comprised in (a) and (b) although in conformity with the ideals by which they are actuated many of them are empowered by their rules to relieve cases of distress. So far as benefits under (a) include annuities the act prohibits a total insurance of more than 152 a year. Similarly insurance on life, whether through one or more societies may not exceed 1300, exclusive of bonus.

It may be conjectured that the English friendly societies are tenuously linked with the mediaeval gilds, the numerous objects of which included most of the purposes which the modern friendly society serves. Very few societies have survived from an earlier period than the i 8th century, but there is ample evidence that towards the end of that century the system was widely estab lished. It was, for example, sufficiently important to receive a considerable amount of attention in Sir F. M. Eden's The State of the Poor published in 1797, while the same author issued in 18o1 his Observations on Friendly Societies for Maintenance of the Industrious Classes During Sickness, Infirmity, Old Age and other Exigencies in which he referred to returns he had obtained in respect of some 5,117 societies enrolled under the Act of (the first statute relating to friendly societies) and came to the conclusion that the total number of societies in existence was about 7,200. It is also on record that between 1793 and 1828 some 20,000 rules of societies—many of which no doubt had but a brief existence—were enrolled among the records of the courts of quarter sessions under the Act just mentioned. The financial arrangements of these early societies were primitive, and failures were evidently sufficiently numerous to receive the attention of parliament. The appendix to the later editions of Dr. Price's Ob servations on Reversionary Payments, etc., contains a complete set of rates of contribution "prepared at the request of a committee of the House of Commons," apparently before 1789, and "intended to form the foundation of a plan for enabling the labouring poor to provide support for themselves in sickness and old age." The author's conception of the nature of a sickness risk was sound but in the absence of data his assumptions were of necessity hypo thetical. His scheme was, however, so complete as to include an elaborate table of sums payable on the removal of a contributor from one parish to another, in order to enable him to remain in insurance at his original rate of contribution. This latter feature is of special interest as ante-dating by over 120 years the sup posedly novel provisions of the National Insurance Act of 1911 in regard to "transfer values" for insured persons who change their society.

It is an interesting fact that S4 societies established before 1800 were on the English register at the end of 1927 and that 22 such societies were on the Scottish register at the end of 1924. Three of the English societies, two of them of Huguenot origin, date respectively to 1703, 1708 and 1712, a society of still earlier formation (1687) having disappeared but a few years ago. The Scottish registrations include even older cases. The date of the earliest society—the Incorporation of Carters in Leith—is given as 1555, and two other societies are stated as founded respectively in 1634 and 167o.

While the purely local societies were multiplying in the early years of the 19th century two other movements were developing. One of these, that of the "county" type of friendly society, was promoted by the rural gentry and clergy, and was distinguished by the correctness of the financial principles adopted and by the com pleteness of the administrative machinery set up on a county basis with devolution of details to parish agencies. The whole cost of management was frequently met from funds contributed by the patrons, in whom control was vested, and insurance of a sub stantial character was thus brought within the means of the rural population in various parts of the country. A few societies of this class, e.g., the Hampshire Friendly Society, have achieved considerable success but the county societies never obtained a posi tion commensurate with their merits as insurance institutions and their place in the friendly society world is now quite inconsider able. The other movement, that of the "Orders," was destined to transform the character of the whole friendly society system- In speaking of these bodies it will be useful to employ this (their own) designation of orders, rather than the cumbrous description of "societies having branches" by which they are identified in the Friendly Societies' Act. The first of the orders to take definite form was the "Independent Order of Oddfellows, Manchester Unity" which, established in Manchester in or about the year 181o, spread rapidly through the industrial districts of the North of England and eventually extended its "lodges" throughout the whole country. Modestly imitating the ritual and symbolism of Freemasonry, its professions of secrecy, with signs and passwords, no less than its charitable designs, made a strong appeal to the social instincts of the tradesman and the better-paid artisan. At the outset its financial arrangements were entirely devoid of any scientific basis, but this came later with the gradual realization by its leaders that insurance and not benevolence was the real foundation of its operations. In the course of time the tide of emi gration carried the society to the United States, to Canada, to Australia, to New Zealand, to South Africa, and elsewhere over seas. The place which the society has achieved in the provident institutions of the British people is indicated by the fact that in 1926 its lodges in Great Britain numbered 4,00o with an adult membership of about 750,000 and funds (including centralized accounts) amounting to nearly £20,000,000.

The Ancient Order of Foresters was the next important organ ization to rise from local obscurity. Also basing themselves on a mixture of ritual and benevolence, its "courts" began to spread from Leeds in 1834. In this case, again, numerical progress was long conspicuous but was unaccompanied by perception of the need of a sound insurance basis and in recent years essential re forms have, in consequence, proved a heavy handicap to progress. Much, however, has been accomplished and the returns for 1926 showed an adult membership in Great Britain and Ireland of nearly 600,000 distributed over 3,438 branches (courts) with funds of £11,650,000.

Other societies of the order type sprang up in the 19th century, and have established themselves with varying degrees of success. The membership, in most cases, is small in relation to that of the two great societies named above, and distinctive features are only to be found in the "temperance" group in which an under taking of total abstinence is required as a condition of member ship. The larger societies of this group are the Independent Order of Rechabites with approximately 700,000 members (of whom, however, nearly one half are juveniles) distributed over about 3,00o branches, called "tents," and the order of the Sons of Temperance with nearly 1,200 "divisions" and about 250,000 members, of whom over 1oo,000 are juveniles.

Societies of two other types came into prominence somewhat later. The first is the centralised society, without a social side, rely ing for support on its stability as an insurance institution. The most prominent example of this group is the Hearts of Oak Benefit Society which, established in 1842 as an offshoot of a society of the same class still in existence, had attained at the end of 1926 a membership of 425,000 with funds of nearly £9,000,000. The other type is that of the deposit society, of which the most im portant representative is the National Deposit Friendly Society. Though established so recently as 1868, on a plan which presents a somewhat curious blend of insurance and private saving—both excellent, but certainly divergent modes of thrift—this society numbered over 760,000 members at the end of 1926 with funds of about f6,000,000. Of the total membership, 420,000 were males of ages over 16, this being, substantially, the comparable figure with those of the other societies to which reference has been made. The corresponding number of women was 202,000, a feature of much interest in the constitution of the deposit type of society in view of the failure of the societies of other classes to attract any large body of women in the 3o years or more during which their doors have been widely open to the sex.

Less important than these major developments but worthy, nevertheless, of mention are the "dividing" societies, many of them unregistered, which exist in great numbers in Britain, espe cially in the large towns. These societies provide small benefits, relatively to the contributions, but share out their funds at intervals, generally yearly. If numbers command respect it must in some degree at least, be accorded to these "slate clubs," "sick and annual" societies, "tontines," etc., as they are variously styled in different parts of the country.

Constitution of the Orders.

The orders, which constitute so prominent an element in the friendly society movement, are organized, both financially and administratively, on somewhat elaborate lines. At the base of the system are the local branches which are distributed over the country in somewhat haphazard fashion; in the rural districts one branch of an order will serve several neighbouring villages, while commonly a large town will have a number of branches, some of them clustering round the centre, while others are scattered over the suburbs. branches are grouped in districts on a geographical basis, there being about 26o such districts in the Manchester Unity of Odd fellows and about 200 in the Ancient Order of Foresters. Above the districts is the central authority of the society, the board of directors in the first of the two large societies and the executive council in the other. As regards legal status the society is entitled to registration under the Friendly Societies Act as a single organ ization, the primary units (lodges, courts, etc.) and the districts being similarly entitled to registration as branches. Under this form of constitution every branch is subject to the rules of the society and though it has its own rules these must comply with the rules of the superior body. All the branch rules are, there fore, to a large extent in common form—and this, nc less than the free interchange of views on the best methods of effecting the common purpose, ensures a considerable degree of uniformity in administration throughout the whole organization. The domes tic affairs of the primary unit are legally subject to its own com mittee of management, though in fact the members, in their fort nightly or monthly meetings, are enabled to exercise whatever share they are inclined to take in the general conduct of business. This unit elects its delegates to the district meeting held half yearly or quarterly and the districts appoint their representa tives to the annual meeting of the society, which in the case of the larger bodies is a somewhat imposing assemblage, the pro ceedings of which are largely devoted to the discussion of major questions of policy. The tripartite arrangement of lodge (or what ever the name of the primary unit), district and order, each with its carefully delimited powers and duties, though appearing some what grandiose if the utilitarian purpose of the society only is considered, is in fact well adapted to the purposes to be served. In most cases the primary unit, the lodge or court, is directly re sponsible to the member for all the benefits under his contract, but retains only the liability to provide the sickness benefits, the death benefits being re-assured with the district. The principal function of the central body, in regard to finance, is to aid any local branches which may fall into difficulty. For many years this obligation was never closely defined and amounted in practice to little more than the grant of eleemosynary relief. In this re spect the conditions have changed considerably in recent years, both the Manchester Unity of Oddfellows and the Ancient Order of Foresters having taken effective steps to secure (under proper contribution arrangements) the fulfilment of the original benefit undertakings of all their branches. The larger society has achieved its purpose by a small charge on the valuation surpluses of the fully solvent lodges, while the Ancient Order of Foresters has adopted the plan of a modest levy on the contributions of the members generally.

Legislation.

Numerous Acts of Parliament for the encour agement and regulation of friendly societies were passed between and 1895 but as practically everything that is of permanent value in these measures (all of which have been repealed) is in corpora.ted in the Friendly Societies Act, 1896, it is unnecessary to examine them in any detail. The Act is administered by the Friendly Societies Registry at the head of which is the Chief Reg istrar, who by the statute, must be a barrister of 12 years' standing, or have been an Assistant Registrar for at least 5 years. In essen tial matters the Act of 1896 re-enacts the Act of 1875, which was based on the report (issued in 1874) of a Royal Commission ap pointed in 1870. The privileges which the Act confers are re stricted to those societies which register under it and the conditions which it imposes apply to those societies only. Unregistered friendly societies are subject, of course, to common law, but are neither protected nor controlled by statute, and the Registry Ofi=ice exercises no f unctions in regard to them. The privilege of registration under the Act has a somewhat wider range than the organizations which are the subject of this article, and includes, for example, working men's clubs and cattle insurance societies.The condition of registration is the adoption of rules providing, inter alia, for the following matters: I. The objects of the society; these must be chosen from amongst the objects specified in the Act. 2. The terms of admis sion of members. 3. The conditions under which a member may become entitled to benefit. 4. The mode of holding meetings, and the right of voting. 5. The manner of making, altering, or rescinding rules. 6. The appointment and removal of trustees, committee of management and other officers. 7. If the society is one with branches, provision is to be made for the composi tion of the central body, and the conditions under which a branch may secede from the society. 8. The investment of the funds. 9. The keeping of the the accounts, and audit thereof. io. Annual returns to the registrar. i i. The manner in which disputes shall be settled; decisions arrived at in accordance with the rules are binding, are not removable into a court of law, and may be en forced on application by the county court. 12. Provision for the expenses of management. 13. Quinquennial valuation.

The

rules, in fact, set out the conditions of the contract which the members of a friendly society mutually make with each other and of the remedies which the law provides to secure its fulfil ment. It will be observed that although the society is required to state in its rules what are its benefits and the conditions under which they are payable, no conditions are imposed upon it. There is no compulsion to adopt an actuarially sound table of contribu tions (except for the insurance of annuities) or to administer the benefits in any particular way. The members, as Sir Edward Brabrook says (Provident Societies and Industrial Welfare, p. 52), "are left entirely to their own discretion as to the soundness of the conditions on which they grant insurances." It may be ob served also that while every society is required to submit its finan cial position to valuation at quinquennial intervals (unless ex empted by the registrar on the ground that valuation is inappli cable to its undertakings, e.g., a dividing society) there is no com pulsion on the members to take steps to rectify any unsoundness which the valuation may reveal. The registrar may do (and does) much, through the influence which his position enables him to exercise, to secure the due consideration of valuation results on which action should be taken, but he has no powers save those which in extremity the requisite number of the members may call upon him to exercise.A registered friendly society has certain privileges of which the more important are the following : 1. It can legally hold land and other kinds of property in the names of the trustees. 2. Where the property is stock in the funds, it may be transferred from a deceased or absent trustee by order of the chief registrar, without other legal proceedings. 3. Other property passes from one trustee to another without con veyance or assignment. 4. The trustees can invest the society's money without restriction of amount in a trustee savings-bank, or the Post-office savings-bank. 5. They can discharge a mortgage by merely endorsing a receipt upon it, without a reconveyance. 6. The trustees are entitled to claim priority over creditors in re spect of property of the society. 7. Documents of the society are exempt from stamp-duty. 8. Members above sixteen years of age may nominate the recipients of sums not exceeding f loo, pay able at their death by the society, and the trustees, where a mem ber dies intestate and has made no nomination, may pay to the person who appears to them to be legally entitled, and such pay ment is a good discharge to the society. 9. Societies can settle disputes in any manner for which the rules provide, and thus avoid the cost of litigation. 1o. Societies are free of income-tax on their interest from investments.

Ordinary Friendly Societies.-The

primary benefit is the weekly allowance during sickness, to which is usually added a pay ment on the death of a member or his wife. The sickness benefit insured is generally from los. to 20S. a week; the predominating rates are probably los. and 12s. except in and around London where insurances for 18s. and 20s. a week are common. Sickness benefit at the full rate is usually payable for 26 or 52 weeks af ter which, if incapacity still continues, it is reduced by one half. In many cases there is no further reduction, but under the rules of other societies half pay is limited to the same period as full pay and is succeeded by quarter pay. Benefit at the low est rate is in most cases continued during incapacity, which may extend over many years. Difficult problems have been created by the sickness claims of aged members, in regard to whom it is im possible to distinguish between incapacity due to sickness and the infirmity of old age. Sickness benefit has, in general, been paid continuously to those beyond work, but the strain of permanent claims has everywhere absorbed a disproportionate part of the resources of the societies and the institution of old age pensions by the State is leading them to a wise limitation of the insurance of sickness benefit to the working ages of life (terminating at 65 or 70) so far as new entrants are concerned. In most cases the contributions are graduated according to age at entry, in accord ance with actuarial tables. At the age of r8, for instance, a con tribution of 5d. a week (to which id. a week must be added for management expenses) will provide a man, according to the rules of one society, with a sickness benefit terminable at the age of 70 of 125. a week for 26 weeks and 6s. a week for the remainder of sickness, together with "funeral benefits" of £12 for himself and L6 for his first wife; the corresponding rate (also subject to addition for management expenses) for an entrant aged 27 is 6d. and for one of 35, is 72d. Under the stress of the competition of the "deposit" societies the older organizations have in recent years made a notable departure from their original objects and have put forward schemes combining insurance (on a sound actuarial basis) with personal savings. Under this plan the member is free to draw upon his savings account at his option and to withdraw the amount to his credit (less a small deduction) on terminating his membership. The amount accumulated is payable in any case on arrival at a stipulated age, generally 65, and is also payable on the death of the member should that occur before he reaches this age.As an example of this class of benefit, one society offers to a male entrant of 16 years of age (last birthday) for a contribution of 15s. a quarter, inclusive of management expenses, a sickness benefit of 20s. a week for 26 weeks, followed, if necessary, by los. a week for a further 26 weeks, and 5s. a week for the re mainder of illness, and at the age of 65 (when contributions and sickness benefit cease) from his personal account a lump sum of over £210 if he is classed as engaged in an "ordinary" occupa tion, or of about £130 if his occupation is scheduled as "haz ardous" and his sickness risk is, in consequence, above the general average. These amounts are subject to possible increase from valuation surplus. In the event of a member's death before he reaches the age of 65 the balance of his account is payable, this being made up, if necessary, to a stipulated minimum.

Schemes such as this premise that the entrant to a friendly society is prepared to contribute on a considerably higher level than was formerly deemed practicable, and is equally prepared, so far as private savings are concerned, to utilize his friendly so ciety as a principal instrument of thrift.

Deposit Societies.-The

societies of the deposit class which, as already shown, have advanced remarkably in public favour during the present century constitute a distinct class. All have the common purpose of combining sickness insurance with per sonal savings, and all eschew the orthodox methods of accumula tion of funds in correspondence with the growth of the liabili ties of the insurance side of their undertakings. Under the de posit plan which enjoys the widest popularity the members are in general required to contribute monthly the same amount as they desire to insure for as the daily rate of sickness benefit, a contri bution of 2s. a month (245. a year) thus being paid in respect of a sickness benefit of 1 2s. a week. The contribution so paid is divided between the member's deposit and the "common sick fund" (with which is linked the small "sickness reserve fund") ; the governing body fixes the proportions in which the contribu tions shall be divided, but it is essential to the main purpose of the system that substantial sums shall be placed to the members' deposits and in the particular case under examination the present practice is to carry to them about two-thirds of the contributions. The member's share of the expenses of management, with certain smaller sums, is charged upon his deposit to which also is debited a proportion, varying with sex and age, but averaging about one third, of any sickness benefit which he may claim and of the cost of any medical benefit for which he may have contracted. For the other two-thirds of the cost of these benefits (which ordi narily cease at the age of 70) resort is had to the sick fund." A member may draw at any time upon his deposit, which carries interest at a low rate, and subject to safeguarding pro visions, may add to it by payments in excess of his normal con tributions. Any balance standing to his credit at the time of his death is paid to his representatives while if he leaves the society he 'draws out his deposit, subject to a small fine.The system lends itself to criticism mainly on two grounds, the uncertainty as to the duration of the benefits in the case of the individual and the provision made for the growing liabilities of the "common sick fund." As regards the first of these points, the member is entitled only to full sickness benefit so long as he has a balance in his deposit from which the prescribed proportion of his benefit can be taken. There is at all times, therefore, a risk of exhaustion of the right to sickness benefit. Any resulting hardship is alleviated by the payment from the "common sick fund" of "grace pay," i.e., sickness benefit at a reduced rate, for a limited period after a member's account is exhausted, but no mem ber is allowed to resort to this benefit more than once in five years. It was observed by Sir Edward Brabrook (at the time Chief Registrar of Friendly Societies) in his Provident Societies and Industrial Welfare (p. 68) that under this system "a member who suffers from prolonged sickness may find the relief of the so ciety fail him through the exhaustion of his own bank at a time when he most wants it." The position of the "common sick funds" is theoretically pro tected by a power to levy on the members' deposits if the reserves should be exhausted. The need to exercise this power might, how ever, be attended by serious consequences, and it is matter for regret, in the circumstances, that although the reserves are substan tial, their basis is empirical, and their sufficiency not yet estab lished.

In considering the characteristics of the deposit class a distinc tion must be drawn between the societies whose system may be criticized on the particular grounds just examined and the so cieties of the "Holloway" group. These latter societies, which are chiefly found (and in considerable strength) in the west of Eng land require a high contribution, relatively to the insurance value of the benefits offered, and increase it as the member passes from age to age between the ages of 3o and 65, when sickness benefit terminates; the object of this novel condition in friendly society finance is to provide, in the absence of specific reserves for sick ness benefit, for the growing liability the member brings as his age increases. The claims of each year constitute a first charge on the contribution income of the year, and in normal circumstances are wholly met from this source, there being no recourse to the personal account of a member in respect of his own demands for sickness benefit and no such limitation, consequently, on the amount of benefit that he may draw as the alternative system is held to involve. The balance of the income of each year, after meeting the sickness claims, is divided among the members, and accumulated for their personal advantage. The contribution is so high, in relation to the insurance element of the scheme, that the prospect of a dividend at the end of the year is in all ordi nary circumstances considerable.

The system evidently appeals with success to those who are attracted by a combination of insurance and saving, flavoured by an apparently pleasing uncertainty as to what the "dividend" will be.

Railway Benefit Societies.

The societies in this group, some of which are unregistered, limit their membership to the opera tive staffs of the railway companies. The benefits frequently in clude substantial pensions after the age of 65, while in some cases allowances are made on withdrawal; the contributions are largely supplemented by subsidies from the companies. No doubt because of the quasi-compulsory character of the membership, the companies have accepted a large measure of responsibility for the financial soundness of the societies and the actuarial valuations have frequently been followed by very substantial grants in the liquidation of deficiencies.

Miners' Permanent Relief Societies.

This is a small group, with, however, a membership of some hundreds of thousands, the object of which is to provide allowances, including permanent pen sions, for miners who are injured at work and pensions to the widows (with children's allowances) of miners whose death is due to occupational accident. With responsibilities difficult of assess ment in any case and liable, obviously, to great fluctuations, the financial record of these societies leaves much to be desired. They are, nevertheless, of special interest as showing the efforts made by the workman to meet a risk to which he was particularly subject long before it was decided by Parliament, in the Work men's Compensation Acts, that the liability was one which the employer should be called upon to bear.

Warehousemen's and Clerks' Societies.

This is a very small but interesting group in which the chief subject of insurance is loss of income whether due to sickness or unemployment. The societies of the group originated with the Provident Association of Warehousemen, Travellers and Clerks established for the em ployees of textile warehouses in the City of London in 1871 ; the objects being somewhat beyond those which the ordinary friendly society is permitted to adopt, registration has been effected under a section of the Act providing for "specially authorized" societies. The resources of these societies have been found well in advance of the modest financial design of their benefits and from the substantial surpluses which have accrued, annuities to members in need and other benefits have been added to the original plan.The report of the Chief Registrar (Great Britain) for 1927 gives a summary from which it appears that the number of returns for the year 1926 received from friendly societies (and branches) of all classes was 21,488 these showing a total of 7,429,506, of whom, however, probably not more than about 5,500,00o were adults in sured for sickness benefits. The expenditure on sickness during the year was £4,684,031 and in death claims 11,195,260, the funds at the end of the year amounting to £91,333,723. While the figures of membership are impressively large in total, it is necessary to look at their component items, with the related statistics of earlier years, in order to ascertain the trend of popular favour as be tween the different types of society. Taking first the class of sickness benefit societies, as the registrar styles them, though pay ments at death are almost invariably provided in addition to sick pay, it is shown that 1,193 returns were received from societies including nearly 1,140,000 members with funds of L21,200,000. But of this group 25 societies, led by the Hearts of Oak Benefit Society, accounted for a membership of 88o,000 and funds of Li 6, 200,000, leaving among 1,168 societies about 260,00o members and funds of about £5,000,000. Substantially these represent the sur vivors of the class of independent local clubs in which the friendly society system originated. The number of societies of this type appears to have fallen by about 1,60o between 1910 and 1916, doubtless as the result of the institution of the system of na tional health insurance which made it as unnecessary as it was hopeless, to prolong the existence of many weak and decaying so cieties. It is, however, an interesting fact that over 400 societies of this class became branches of the orders. The disappearance of those local societies continues, and each year sees a further reduction in their number; between 1916 and 1926 nearly 400 of them were removed from the register. The membership of the orders on December 31, 1926, was well over 3,000,00o and their funds exceeded £43,000,000, the group thus representing nearly one-half of the whole friendly society movement, both in funds and membership. The number of branches making re turns was 18,019, the average membership being under 200. So far as numbers are concerned the societies of this type have not made progress in recent years. While funds have grown since 1910 by over £ 15,000,00o the number of branches making re turns has fallen by over 2,000, and little increase in the total number of members is observable. In contrast, the deposit socie ties, numbering about 1 oo, have achieved continuous and rapid progress. Between 1915 and 1926 their membership increased from 600,000 to over 1,i00,000 and their funds from £5,300,000 to £ 14,200,000. Of the varied other types of society on the register mention need only be made of the statistics of the "dividing" so cieties. The membership of this group (which is probably ex ceeded by that of unregistered societies of the same type) is prac tically stationary at under half a million. The amount of funds in hand—about £600,00o—does not increase, in any material degree, from year to year. This is, of course, explained by the leading feature of the constitution of these societies—the yearly "share-out." Finance.—From the large amount of their funds the friendly societies rank as capitalists of some importance, and much atten tion is devoted to the subject of investment. Although considerable sums are invested in Government stocks, and in loans to local authorities, the favourite security is the mortgage on house proper ty. In great numbers of cases advances have been made to mem bers to enable them to purchase their dwellings and in some direc tions the system of repayment in instalments has been in success ful operation for many years. The rise in the market value of money since the World War has been quickly appreciated by the friendly societies, and the resulting increase in the rates of interest secured on their funds has been a powerful factor in the financial progress to which reference is made below.

It was inevitable from the circumstances in which the friendly societies originated and developed that they should long have lain under the imputation of financial unsoundness. The very fact that they were conducting insurance business, for which an ac tuarial basis was essential to security, was but tardily recognized, and it was not until the middle of the 19th century was approach ing that tables of an authoritative character were compiled to show the rates of sickness and of mortality to which their mem bers were subject at successive ages. These tables provided the means of framing actuarial estimates of the financial position of the societies, but it was not until the Friendly Societies Act of 1875 enforced them that such estimates--in the form of quinquennial valuations—were generally obtained, and many years had to elapse, and a vast amount of propaganda to be undertaken, before the results of early and long-continued insufficiency in financial arrangements could be overcome. Improvement has been accelerated in recent years by the increase in the rate of in terest obtainable on investments and by the decline in sickness claims which set in during the World War and continued for sev eral years afterwards. Valuations (which are not required from deposit and dividing societies) were received in the five years ending Dec. 31, 1926, from 55,030 societies and branches, and these showed surpluses to the amount of about £8,400,000 and deficiencies of about £6,000,000. It is thus evident that while much remains to be done before all the friendly societies of Great Britain are solvent—and for some among them the task may be too great—there is conclusive evidence of soundness, and promise of the enlargement of the contractual benefits, over a great part of the field.

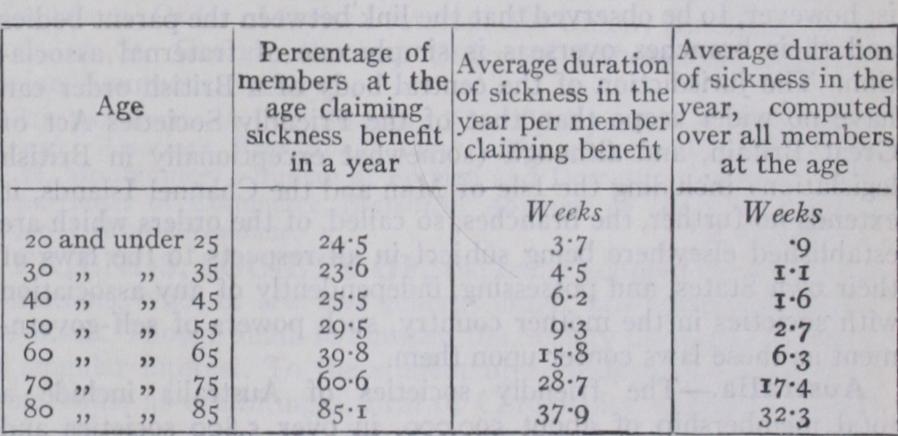

The data providing the rates of sickness and mortality on which valuation tables are based were formerly obtained from returns supplied by the friendly societies, in compliance with a statutory requirement, at quinquennial intervals covering the period between 1836 and 1880. The first returns so received, relating to the period 5836-40, were analysed by a distinguished actuary (Nei son) who himself published the results of his observations and the returns for 1846-5o were dissected, unfortunately on such a theoretical basis as to render the results of little value for prac tical purposes, by an actuary in the public service. An analysis of the returns for the period 1856-8o was made by the actuary to the registry of friendly societies, but his report was not avail able till 1896, by which time the greater part of the data brought under review had become out of date. Meanwhile, the Man chester Unity of Oddfellows taking advantage of the requirement to render quinquennial returns had on three occasions analysed its own experience, the latest of the resulting tabulations, that of the period 5866-7o, being generally accepted for many years as the authoritative standard of sickness experience. A similar course was followed by the Ancient Order of Foresters with the quinquennial returns of its branches for the period 1871-75. These societies thus supplied themselves—and the world—with the only authentic bases of valuation that existed for the half century during which the movement was making its greatest progress. The government report of 1896 indicated that accord ing to the latest data of which it treated—that of the years 1876-80--the sickness liabilities of friendly societies had risen seriously. The societies were thus placed in a difficulty, for even this experience was nearly 20 years old at the time the report was published, and as Parliament had in 1882 abolished the quinquen nial returns (under advice, presumably, that sickness was more or less static and that a sufficient volume of facts as to its incidence had been collected) and no information as to current conditions was available, either to modify or to confirm the disquieting re sults which the last official report brought out. In these circum stances the Manchester Unity of Oddfellows decided on inde pendent action and again collected the experience of its branches, the years selected being 1893-97. The data so obtained, for the assemblage and analysis of which Alfred Watson (then one of the actuaries to the society) was responsible, extended over 3,000,00o years of life and included 7,000,000 weeks of sickness. It represented by far the largest body of friendly society records ever brought together, and the report exhibiting its results was issued in 1903. No other investigation of the kind has subsequently been made and the tables obtained from this experience are there fore still in general use as the standard of sickness risks; in this Connection they supplied the financial basis of the National Health Insurance Act. The importance to the industrial classes of an adequate provision against the risk of sickness is illustrated by the statistics of this experience from which the following figures are extracted:— It will be seen that while till the age of 5o has been passed there is no material increase in the proportion of members requiring sickness benefit in a year, the average duration of incapacity in creases steadily as age advances. Permanent invalidity accounts for much of the weight of sickness at the higher ages but disre garding incapacity beyond a duration of 26 weeks (at which, for the purpose of illustration, a dividing line may be drawn) it is an arresting fact that at the important ages 6o-65, where the work man in the normal case must still rely for his maintenance upon his labour, the Manchester Unity experience suggests that about 33% of the insured will have occasion to claim sickness benefit in the course of a year and this for an average period of seven weeks. Partial statistics of National Health Insurance afford some indication that in the early years after the war the percentage of claimants at these ages fell to about 25 (the average duration of seven weeks remaining stable), but there is reason to think that this improvement has not been fully maintained. Whichever fig ures be taken, it is evident that sickness insurance on a reliable basis is essential to the security of the wage-earner and those de pendent upon him.