Fugue

FUGUE, in music, the mutual "pursuit" of voices or parts. It was, up to the end of the 16th century, if not later, the name applied to two art-forms. (A) Fuga ligata was the exact reproduc tion by one or more voices of the statement of a leading part. The reproducing voice (comes) was seldom if ever written out, for all differences between it and the dux were rigidly systematic ; e.g., it was an exact inversion, or exactly twice as slow, or to be sung backwards, etc., etc. Hence, a rule or canon was given, often in enigmatic form, by which the comes was deduced from the dux; and so the term canon became the name for the form itself and is still retained. (B) A composition in which the canonic Ityle was cultivated without canonic restriction was, in the 16th century, called fuga ricercata or simply ricercare, a term which is still used by Bach as a title for the fugues in Das musikalische O p f er.

Fugue is a texture the rules of which do not suffice to deter mine the shape of the composition as a whole. Schemes such as that laid down in Cherubini's treatise, that legislate for the shape, are pedagogic fictions; and such classical tradition as they repre sent is too exclusively Italian to include Bach. Yet, strange to say, the Italian tradition in fugue style is represented by hardly any strict works at all. Under the general heading of CONTRA PUNTAL FORMS many facts concerning fugues are discussed; and only a few technical terms remain to be defined here.

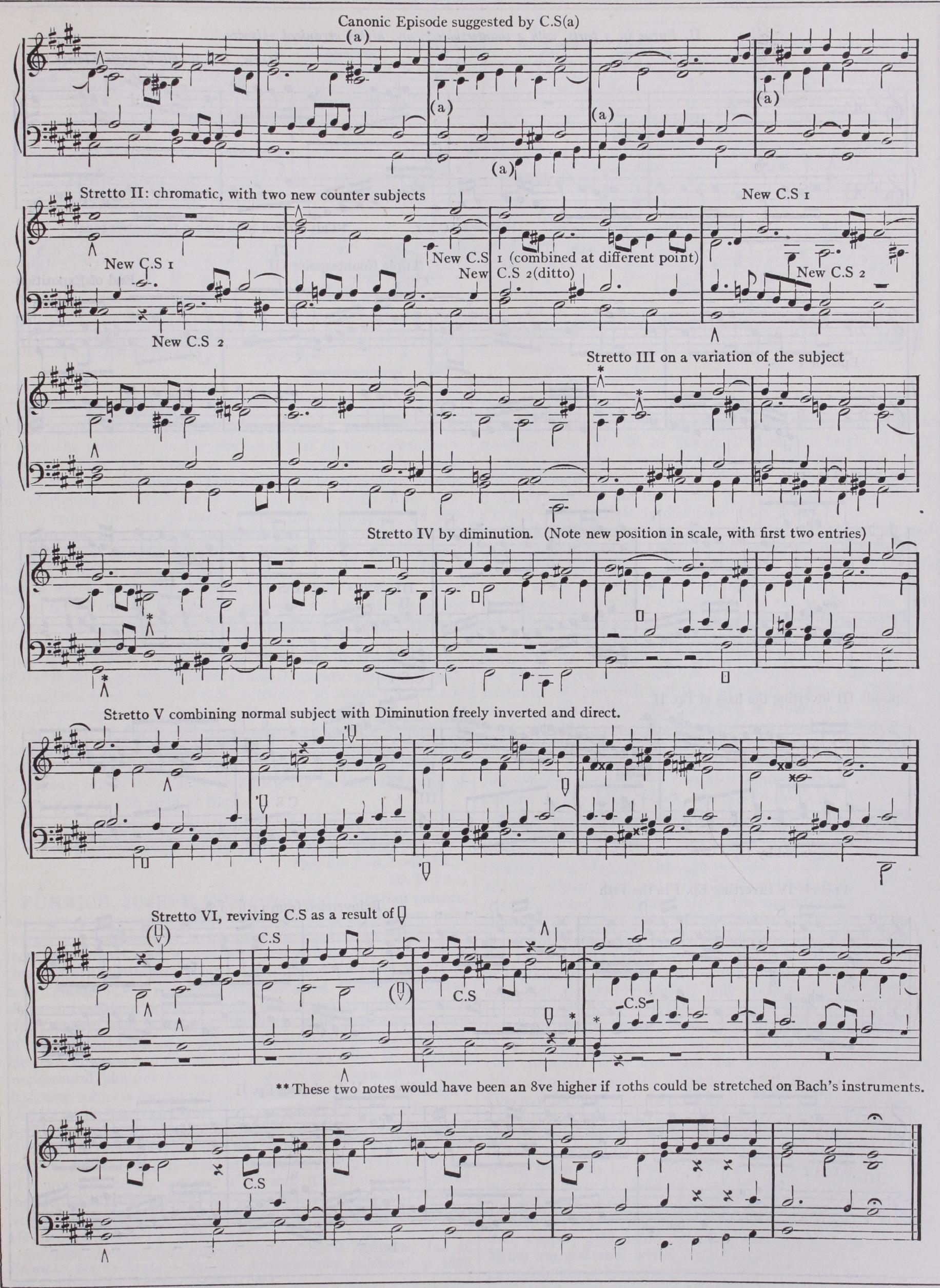

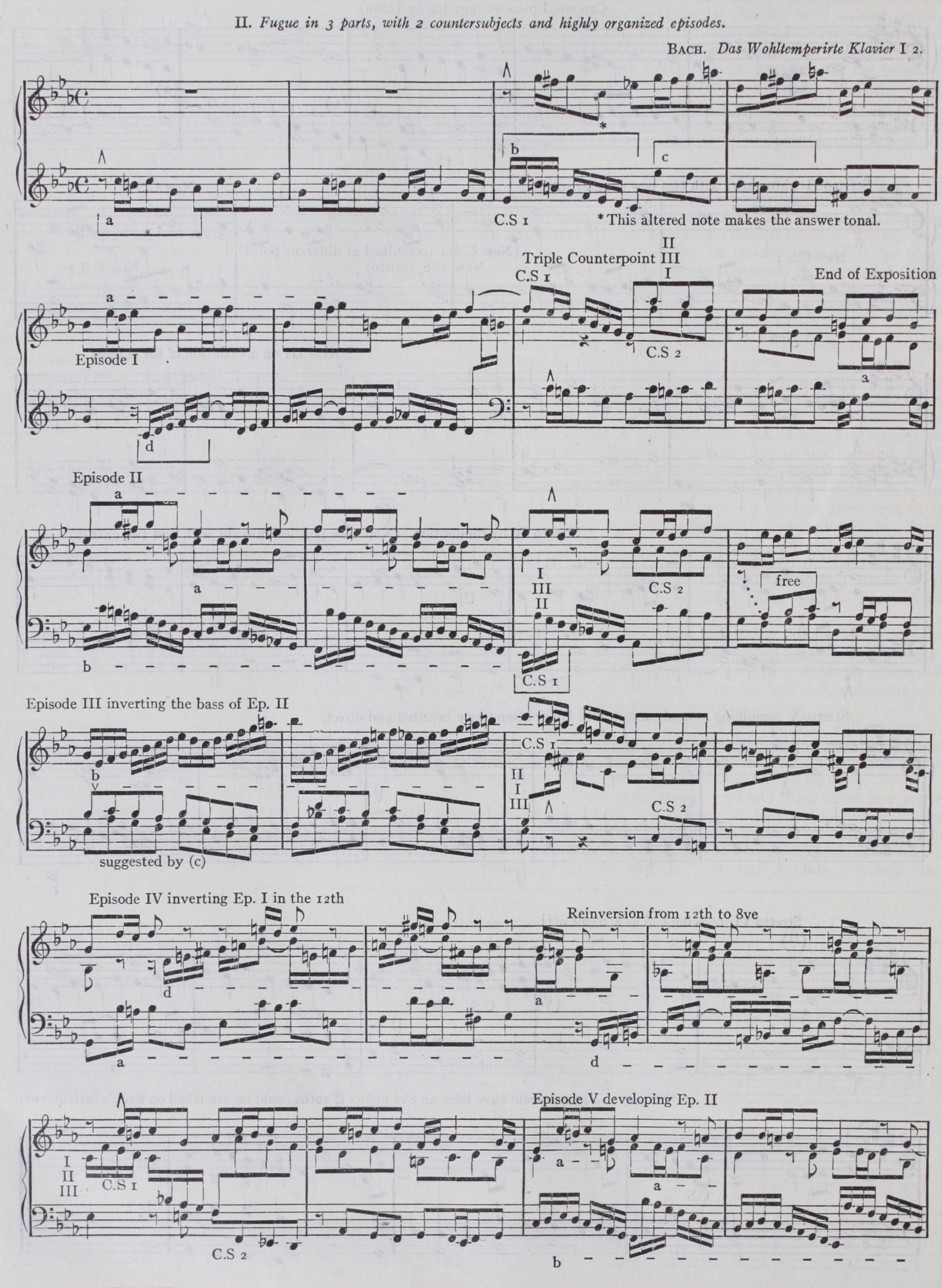

(i.) If during the first entries or "exposition" of the fugue, the counterpoint with which the opening voice accompanies the answer is faithfully reproduced as the accompaniment to subse quent entries of the subject, it is called a countersubject. Obvi ously the first countersubject may continue with a second when the subject enters in the third part and so on. The term is also applied to new subjects appearing later in the fugue in combi nation (immediate or destined) with the original subject. Cheru bini, holding the arbitrary dogma that a fugue cannot have more than one subject, applies the term to the less prominent of the subjects of what are commonly called double fugues, i.e., fugues which begin with two parts and two subjects simultaneously, and so also with triple and quadruple fugues. It is remarkable that Bach (with only three known exceptions) never writes this kind of double fugue, but always introduces his new subjects later.

(ii.) Episodes are passages separating the entries of the sub ject. There is no reason for distinguishing episodes that occur during the exposition from later episodes. Episodes are usually developed from •the material of the subject and countersubjects; they are, when independent, conspicuously so.

(iii.) Stretto is the overlapping of subject and answer. A stretto maestrale is one in which the subject survives the over lapping. The makers of musical terminology have no answer to the question of what a non-magistral stretto may be.

(iv.) The distinction between real and tonal fugue is a matter of detail concerning the answer. A fugal exposition is not in tended to emphasise a key-contrast between tonic and dominant. Accordingly the answer is (especially in its first notes and in points that tend to shift the key) not so much a transposition of the subject to the key of the dominant as an adaptation of it from the tonic part to the dominant part of the scale or vice versa ; in short, the answer is as far as possible on the domi nant, not in the dominant. This is effected by a kind of melodic foreshortening on principles of great aesthetic interest but diffi cult to reduce to rules of thumb. The rules as often as not pro duce answers that are exact transpositions of the subject; and so the only kind of "real" fugue (i.e., fugue with an exact answer) that could rightly be contrasted with the tonal fugue would be that in which the answer ought to be tonal but is not.

The term "answer" is usually reserved for those enfries of the subject that are placed in what may be called the "comple mentary" position of the scale, whether they are tonal or not. Thus the order of entries in the exposition of the first fugue of Das Wohltemperirte Klavier is subject, answer, answer, subject, a departure from the usual rule, according to which subject and answer are regularly alternated in the exposition.

The nature of fugue and of polyphony as building harmony in "horizontal" melodic threads instead of in "vertical" chordal lumps is all summarized by Milton, during no classical period of polyphony, but in the chaotic time half-way between the death of Frescobaldi and the birth of Bach.

His volant touch, Instinct through all proportions, low and high, Fled and pursued transverse the resonant fugue.

Paradise Lost, book XI.

(D. F. T.)