Modern Permanent Fortification

MODERN PERMANENT FORTIFICATION In the last quarter of the 19th century, two events changed the whole outlook on permanent fortification. One, not fully appreci ated at the time, was the power of the breech-loading rifle, in con junction with improvised field works, of stopping an infantry attack, the other the introduction of high explosive shell.

Breech-loading Rifles and High Explosive Shells.—The former was strikingly manifest in the defence of Plevna by the Turks in 1877. The defences, which mainly consisted of small infantry redoubts with artillery in separate battery positions, were only constructed after the first Russian attack. The redoubts, surrounded by a loft. ditch, were square in plan, with parapets 10 to 5ft. above the ground and 14ft. thick. They had a certain amount of head cover of timber and earth and were connected by trenches 4f t. deep. In spite of suffering considerably from artillery bombardment, these works, stubbornly defended by the Turks with breech-loading rifles, held out against all assaults. After five months, it was only through lack of supplies that Plevna capitulated.

The Germans in about 1884 had begun experiments with long shell containing large charges of gun cotton. But it was the experi ments at Ft. Malmaison in France in 1886 that set the military world speculating on the future of fortification. The fort was used as a target for eight-inch shell of five calibres length con taining large charges of melinite. The reported effects of these made a tremendous sensation, and it was at first thought that the days of permanent fortification were over. Magazine casemates were destroyed by a single shell, and revetment walls were over turned and practicable breaches made, by two or three shells falling behind them. It must be remembered, however, that the works were not adapted to meet this kind of fire. The casemates had enough earth over them to "tamp" the shell thoroughly (i.e., increase its power by confining and concentrating its effect), but not enough to prevent it from coming into contact with the mason ry, and the latter was not thick enough to resist the explosion of the big charges. After the first alarm had subsided, foreign engineers set about adapting their works to meet the new projectiles. Revet ments were enormously strengthened, and designed so that their weight resisted overturning. Concrete roofs were made from six to ten feet thick and in many cases the surface of the concrete was left bare so as to expose a hard surface to the shell without tamping.

Successive Fortifications of Metz up to 1899.

Of the fort resses that were strengthened to meet the new conditions Metz is a good example. In 1868-7o detached forts of bastion trace, such as St. Julien (Manteuffel) were built within 3,000yd. of the old enceinte, which was left unaltered. Af ter 1870 the Germans added forts of the polygonal type, such as Prinz Auguste, with wing bat teries to reinforce the intervals. Later the perimeter was strength ened by infantry positions, shelters and armoured batteries. Fi nally in 1899 the more modern forts of Sauley and Pont du Jour, 9,000yd. from the place, were commenced. The distances of the detached forts from the place were thus being increased to keep pace with the range of siege howitzers. The minimum distance was considered to be 8,000yd. In practice, however, the position of the forts had to be determined by the lie of the ground. At Verdun the distances varied from 3,00o to 12,o0oyd., Bucharest 8,000 to 12,000, Copenhagen 8,000 to 1 o,000 and Paris 15,000 to 18,000. With the extension of the perimeter came the increased difficulty of defending the intervals between the forts. The flank ing fire of some of the guns in the forts played an important part, but the main defence rested on a chain of redoubts and infantry positions with fire trenches, obstacles, bomb-proof shelters and communications, between the forts. To stop infiltration and as the last line of the "step by step" defence the enceinte where pos sible was retained. This was done more as a concession to tradi tion than for any solid reason, as it would be impracticable to en close a modern town with a continuous enceinte, and if provided it would hardly be a favourable position for the last stage of a defence.Although the forts were all designed to contain guns of the safety armament (i.e., permanently in position ready to come into action as soon as war broke out) it was realized that for protracted defence a considerable force of artillery outside the forts would be required. If positions were prepared before-hand with concrete or armour considerable expense would be entailed, and the dis positions would be fixed without reference to the enemy's front of attack. A compromise was therefore effected, only the most important batteries being completely protected, while positions for the remainder were prepared and the necessary communica tions made.

Types of Detached Forts.

Of the many types of detached forts, there may be mentioned forts designed without any cov ered way, which showed that offensive action was no longer ex pected from the garrison of the fort but was the duty of troops in the intervals. On account of the difficulty of building a revet ment strong enough to withstand breaching fire the scarp was usually omitted. The slope of the rampart was carried down to the bottom of the ditch and protected with a steel fence and wire entanglement obstacles.

Armour.

It will be noticed that armour is included in many modern examples. In 186o Brialmont had employed armoured tur rets at Antwerp in the forts which commanded the Scheldt. But for land purposes engineers were slow to adopt it. It was thought that the deliberate fire of a battery on land would be so accurate that, with successive blows, it could break down the resistance of the strongest shield. When this was not found to be the case, opinion turned and practical types of cupolas were produced. It was argued that the object of fortifications is not to obtain resist ing power without limit, but to enable men to defend themselves and use their weapons for as long as possible against a superior force, and that from this point of view armour adds strength to defensive works. Of the various forms of armour, revolving cupolas with flattened domed tops are generally used. Turrets which are cylindrical with flat tops are more conspicuous and pre sent vertical targets. They both emerge from a mass of concrete which is strengthened round the opening with a collar of steel. Casemates and shielded batteries, in which guns fire through a fixed embrasure or port hole, are considerably cheaper, and have the greater strength of a fixed structure. But the arc of fire of the gun is very limited and the embrasures, which are the weak est points of the system, are—except in the case of Bourge case mates for flanking batteries—constantly exposed to the fire of the enemy. They are, however, well suited for flanking batteries and for barrier forts, where the Italians have used them for the end of the Mont Cenis tunnel.

Fig. 9 shows a cupola for a pair of 3-in. guns. The shield is of nickel steel. The guns are muzzle pivoting and the cradles are thickened out near the muzzle so as to close the port as much as possible. The recoil is curtailed within narrow limits so as to economize space. To facilitate elevation the breech of the gun (with muzzle pivoting the breech has, of course, to be moved through a much larger arc than with ordinary mounting) is bal anced by a counter-weight. The cupola is raised and lowered by means of a lever and counter-weight and can be locked in the raised position. It can be turned through a complete circle in about one minute.

Of all the countries that adopted armour it was Rumania that used it the most. Bucharest was defended by 18 main armoured forts (designed by Brialmont) some 4,5ooyd. apart and 11,000 to 12,000yd. from the town, with 18 small forts and intermedi ate batteries. The typical armament of a main fort was six 6 in. guns in three cupolas, two 8.4 in. and one 4.7 in. howitzer in cupolas and six small Q. F. guns in disappearing cupolas. For the defence of the Sereth line where the three Russian lines of ad vance across the river passed through Focshani, Nemolassa and Galatz, the "Schumann system of armoured fronts" (1889-92) was adopted. This system dispensed entirely with forts and relied on the fire of protected guns disposed in several lines of batteries of Q. F. guns and howitzers in cupolas. In the Focshani works there were 71 batteries on a 12 m. semicircular front, disposed in three lines about 500 yd. apart and divided into groups. The nor mal group consisted of five batteries, three in the first line each consisting of five small Q. F. guns on travelling mountings, one in the second line of six Q. F. guns in disappearing cupolas, and one in the third line of a 5 in. gun in a cupola and two 8.4 in. shielded mortars. The immediate defence of the batteries con sisted of a glacis planted with thorn bushes and a wire entangle ment. It was claimed that with this system an attack could be stopped by artillery fire alone, but the difficulties of command, fixed battery positions, and lack of infantry defence, especially at night, or in a mist, were sufficient to condemn it by all authori tative Continental opinion.

Unarmoured Systems.

While European nations were includ ing armour in their permanent fortifications, there were many dis tinguished soldiers entirely opposed to its use. In England Maj. G. S. Clarke, R.E. (now Lord Sydenham) published in 1900 a notable book on Fortification. He condemned the inclusion of artillery in forts which formed conspicuous and easy targets, and for the defence, advocated strong permanent infantry redoubts supplemented by field defences. These guaranteed the safety of the guns behind them, which could then dispense with armour and take every advantage of concealment, alternative positions and mobility. With guns in detached forts, a compromise had to be effected between the most suitable infantry and artillery posi tions, to the detriment of both. When separated, the infantry re doubt could be sited in the best tactical position to give effect to rifle and machine gun fire, while the guns were placed in concealed positions in rear. It was only in the special case of barrier forts that he considered armour necessary.In a typical infantry redoubt of the kind suggested, the form is simple and in order to reduce the chance of' being hit the plan is shallow. Invisibility is secured by low command, easy slopes and the judicious planting of trees. If it is intended for 30o men, there is shell proof accommodation under the parados for three quarters of the garrison. A parapet is provided for frontal fire but there are no traverses.

Port Arthur.

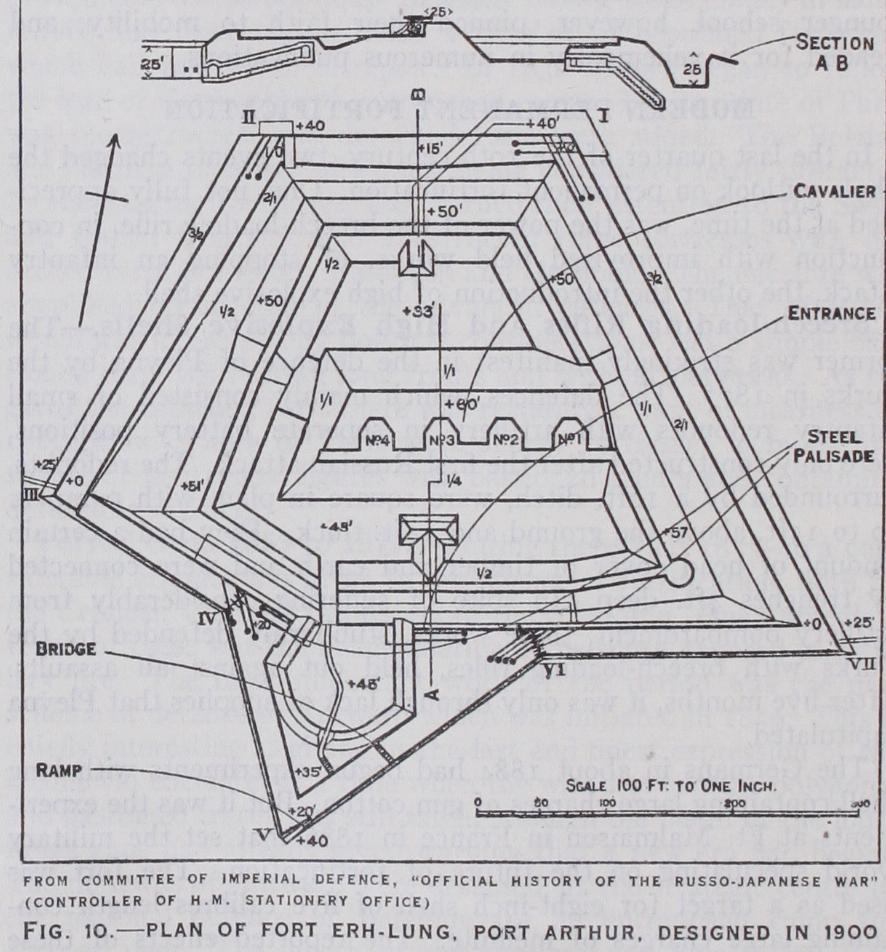

Out of the welter of theory and experiment Port Arthur in 1904 was the first fortress to be put to the test of modern war. Although designed in 1900 the permanent defences. as can be seen from the plan of Fort Erh-Lung (fig. s 0), were of the 1870 type of detached fort.Owing to the of funds only three forts on the north-east side had been built, while to the north-west, the important position of 203-Metre Hill (fig. 15) had no permanent defences. In spite of the fire of the new Japanese 1 i in. siege howitzers, and of the most determined attacks the siege lasted five months (see PORT ARTHUR). The guns in the forts, on account of their conspicuous position, were soon silenced ; but the forts themselves, surrounded by deep ditches cut out of solid rock, held out against repeated assaults until blown to pieces by mining. The great stopping power of rifles and machine guns from improvised defences, even when subjected to the fire of heavy howitzers, was again brought out. This power is increased when the line is strengthened by perma nent infantry forts with deep ditches. To coop up artillery in conspicuous infantry forts is a mistake, and the weakness of a linear defence on the observation line and without depth is appar ent. If one position is captured the remainder of the line can be taken in flank and rendered untenable.

Infantry redoubts having proved their value as keystones of the defensive line, Schroeter in 1905 proposed a new variation of this type. The command in this case is lower than in Sir George Clarke's work, while the plan is more complicated and arrange ments for close flanking defence have been introduced. These works, however, are the infantry supporting points in a line which contains forts of the triangular type with guns and ar moured batteries. To obviate the weakness of this type of linear defence, and to protect the batteries from any penetration by the enemy between the redoubts, the Germans at Metz built a new form of fortified work known as the "feste." This, as its name in dicates, is rather a self-contained fortress on a small scale than a fort in the old sense. The "festes" built just prior to 1914 covered a large irregular area some 1,200 yd. in depth and width. Within their wired perimeter were sited all the elements of the defence both for infantry and artillery. Strong self-contained infantry works were situated at each of the salient angles, while the batteries (generally 6 in. howitzers and 4 in. guns) were dis posed within the area with their weapons in revolving steel cupolas embedded in concrete. Ditches 20 ft. deep, wired at the bottom and flanked by loopholed galleries, protected the outer face of the infantry works. Each battery and work was surrounded by wire and the main perimeter wire was sunk six feet deep and flanked by the redoubts. There were numerous steel and concrete command and observation posts for the artillery and infantry, and casemates protected by nine feet of concrete were provided for the whole garrison. Deep underground galleries and a complete tele phone system connected the various parts of the "feste." Developments of the 20th Century.—While land defences were thus being evolved, changes due to the great economic and industrial developments of the early loth century were affecting not only the design but the role of permanent fortification. The conception of a fortress as a ring of defences protecting an im portant point, and capable of withstanding an investment unsup ported by a field army, though by no means abandoned, was being modified. The ring fortresses of the 19th century, which protected important places such as capitals and arsenals, and served as secure bases for field armies, or refuges for beaten ones, were no longer capable of fulfilling their role. These changes were due to two main reasons. Firstly, the increased size of armies provided by universal service necessitated the employment of several lines of communication, wide bases, and large areas for their concen tration and deployment. Secondly, the greatly increased range and destructive power of artillery necessitated the extension of the per imeter to such a degree that for the defence of a fortress a field army was required. Zone fortification therefore was beginning to be established in the highly-organized industrial areas of Western Europe. Reliance, however, was still placed on self-sufficing girdle fortresses, such as Paris, Antwerp and Bucharest, and in the less organized areas of Russian Poland.

Use of Fortified Areas.

Bef ore examining the history and trend of opinion on permanent fortification during and since the World War of 1914-18, it is advisable to consider the use and limitations of fortified areas. It is an axiom of war that victory can only be won as the result of offensive action, but a defensive attitude may at times be necessary or even advantageous. For tresses can never win a victory; their role is to gain time and econ omize force. The main uses are:—( ) To delay the enemy on important lines of advance, such as the barrier forts of the Alpine passes, or the fort of Manonvillers, which commanded the main line of railway from Strasbourg to Paris; (2) to protect vital points such as Paris and Antwerp; (3) to canalize the attack and force the enemy, unless he wishes to spend the time and men necessary for the deliberate attack of fortresses, to advance by specified lines (the Trouee de Charmes between Toul and Epinal is an example) ; (4) to act as a pivot of manoeuvre. It was for this purpose that the Germans used the Metz-Thionville zone.

Fortresses in the War of 1914-18.

The comparatively rapid and shattering fall of the Belgian fortresses in 1914 caused a com plete revulsion against permanent fortification. Liege with its I 2 armoured forts fell II days after the opening attack, and eight days after the first use of the German I yin. howitzers, while the centre of the town, with the vital bridges over the Meuse, was captured within the first three days. Namur withstood only four days' bombardment and four of the main Antwerp forts were rendered untenable in three. On the eastern frontier of France the barrier fort of Manonvillers was reduced to ruins in two days. The main fortress zones of Verdun-Toul and Epinal-Belfort were not seriously attacked except at the fort Camp des Romains, which the Germans captured and thus secured a crossing over the Meuse at St. Mihiel. On the other hand Maubeuge, with its permanent fortifications completely out of date and strengthened only by field works, held out for I I days. As a result of these events, the French higher command decided to abandon the perma nent forts of Verdun and to rely entirely on field defences. When the Germans attacked in Feb. 1916, Fort Douaumont was left undefended and charges were laid for the demolition of Fort Vaux; but the electric firing cables having been cut by shell fire, the demolition could not be carried out. Meanwhile it had been discovered that the concrete casemates and steel cupolas of the modern forts had suffered little damage from the heaviest shells. Gen. Petain therefore ordered the forts to be re-occupied. The protected observation posts and shell-proof casemates were found to be of the greatest value, but the absence of the flanking guns which had been removed, and the lack of telephonic and under ground communication to the rear, were severely felt. These forts were generally small—Vaux was designed for 150 men—and except for an occasional 75 or 155mm. gun in a cupola for direct fire, and flanking guns in Bourges casemates, they contained no artillery. The forts were provided with concrete underground galleries and casemates, protected by masonry arches three feet thick, with a three foot cushion of sand between them and the main protective layer of eight feet of concrete; and were enclosed by ditches Soft. wide and loft. deep.On the German western frontier, in order to provide a pivot of manoeuvre for Von Schlieffen's plan for the invasion of France through Belgium, the defences of Metz had been strengthened and extended to include Thionville, while tom. west of Strasbourg the fortress of Mutzig was built to close the Col de Saales road over the Vosges. These fortresses fulfilled their role but were never seriously threatened.

German-Austrian-Russian Frontier.

The fortresses of Poland and Galicia differed from those of France and Belgium in that they were purely ring fortresses, designed to hold the few and theref ore very important road and railway junctions of Poland. Of these, Modlin (Nowo-Georgiewsk) was invested and rapidly fell by siege, Brest-Litovsk and Grodno fell as parts of the battle line, Deblin (Iwangorod) was evacuated by the threat of an encircling movement, while Przmysl alone, with the aid of field works, was successful in withstanding a siege. On the German frontier the fortresses of the Vistula-Torun (Thorn) and Gran denz were never attacked. Of the forward line, however, Konigs berg held two Russian army corps from the battle of Tannenberg, and the small fortress of Lotzen with a strong line of field defences, flanked by the lakes, never gave way.

Effect of Bombardment on Forts.

The difference in the degree of resistance to shell fire shown by the various forts is remarkable. Manonvillers, though not entirely modern, with its two steel cupolas, disappearing 6in. guns, and casemates protected by eight feet of ordinary concrete, became a blazing inferno under the rain of 17,000 shells directed upon it. The garrison, after two days, blinded by the dust and fragments, asphyxiated by the fumes of the constantly bursting shells, and almost demented by the concussion, were rendered quite incapable of defending the fort, which was captured by the Germans without the loss of a single man. The forts of Liege and Namur similarly, when subjected to the concentrated fire of i 7in. howitzers, were soon rendered untenable ; casemates were penetrated, cupolas overturned and the whole structure reduced to ruins. On the other hand, the more modern forts of Verdun appeared to have withstood the heaviest bombardments without vital damage. French writers claim that of the steel cupolas only one was permanently destroyed. At Douaumont 13 out of the 18 casemates remained intact. Forts Moulainville and Vacherauville received 6,000 to 8,000 shells each, of which in the case of Moulainville, 33o were 17in., without permanent damage to casemates or turrets. The difference in the resistance of the forts was due to the higher quality of the French concrete, which was mixed with a large proportion of cement, and laid with the greatest care to ensure the masses being monolithic without lines of cleavage, and also to the great thickness and large masses which are necessary to withstand the overturning and disruptive effects of bombardment. The French cupolas had 3omm. thickness of steel compared with the 22MM. of the Belgian ones. The Belgian forts were large, crowded, and conspicuous targets; they contained guns of the main artillery armament, and were sited on commanding positions. In spite of the lessons of Port Arthur, they were only built to withstand shells up to Bin. The Italian barrier forts in the battle of the Isonzo failed because their armour and concrete were not sufficiently thick and there was no protection against gas, while the small Austrian works in the south of Tirol, although bombarded by 12in. howitzers, held out for months.

Value of Permanent Works.

From the lessons of the World War there have again grown two schools of thought. On the one hand it is argued that the fortresses of the Franco-German fron tier completely justified the money expended on them. By their existence they forced Germany to violate the neutrality of Bel gium and so brought the British empire against her. The more modern forts proved their ability to resist bombardment by the heaviest shells and saved many casualties. Verdun, as a pivot of the battle line, was of incalculable value during the decisive battle of the Marne, and later as a bastion in the trench system. Liege, in spite of its comparatively rapid fall, gained the allies at least four days, enabled the French army to change front and the British to come into line. Paris as a pivot of manoeuvre, forced the Ger man invasion westwards and so exposed their flank to Manoury's attack. Antwerp kept two German corps from the decisive front, and "every day gained at Antwerp meant a French port saved." Maubeuge, Przmysl and Konigsberg all detained important forces from the battles of the Marne, Cracow and Tannenberg. Strasbourg and Metz-Thionville fulfilled their role as a pivot for the German wheel. The expenditure on keeping these fortresses up to date was not great. The average annual amount spent on the defences of Verdun and the heights of the Meuse for the 4o years prior to the war was £200,000, i.e., less than the cost of a de stroyer; while the total spent on Metz was about equal to the cost of a battleship. Battleships are not expected to last more than 12 or 15 years; they are then considered obsolete and replaced. The other school of thought point out that the inherent weakness of fortresses is in their immobility. Once built they remain, and when war comes may not be in the right place. Their position and extent are accurately known. They rapidly fall out of date and are expensive and difficult to renew. Apart from the expense in volved, their reconstruction is a heavy feat of engineering, and not only takes time but frequently renders them useless for the period of the repairs. In 1914 four of the principal works of Bel f ort were out of action, as they were being rebuilt. New weapons for their destruction are rapidly invented and made. Manonvil lers, Liege, Namur and Modlin (Nowo-Georgiewsk) were de stroyed with ease and rapidity. Reliance based on the security afforded by fortresses may be a delusion. Of the three great entrenched camps of Antwerp, Paris and Bucharest, designed as a refuge for the Government and army, not one performed its role. Antwerp, on which much money had been expended, and considered by the Belgian nation as up to date, was given up by the field army and Government as soon as it became a question of withstanding a siege or continuing the war in the open. Buch arest was surrendered as the result of a battle in the foreground ; while Paris, though valuable as a pivot of manoeuvre, was evacu ated by the Government. Field defences, by their concealment, dispersion and facility for rapid renewal, are just as effective for defence as permanent fortification. It was not the permanent forts of Verdun and Przmysl but the trench lines of the advanced position and intervals that stopped the enemy. At Verdun the important tactical position of Mort Homme, defended by nothing but field defences, held out against the heaviest bombardments and attacks for six weeks, and caused the attackers terrible casualties. The expenditure is undoubtedly great, and the money could be more profitably spent on the field army, as, if the field army is overwhelmed the fortresses must fall.

Conclusions Drawn from the War of 1914-18.

It is evident that fortress areas, even when not attacked, fully justified their existence, but ring fortresses are obsolete. It was not Verdun the fortress, but Verdun as a solid bastion of the battle line, that resisted all assaults. The immense perimeter, now necessary to protect vital spots against long range guns, requires a large garri son ; and for the ammunition and supply of this garrison for any length of time, railway communication must be kept open. There are, however, rare occasions when for political reasons it may be necessary to hold a ring fortress for a limited time. In the north ern salient of Poland it is conceivable that the Poles, for political reasons alone, might wish to retain command of Vilna, while with drawing from the remainder of the salient until their field army was ready to advance. Fortress areas equipped with concrete and armoured forts are expensive and slow to build ; if they fail to gain the time they were calculated to gain, or require for their defence more men than the enemy would require to mask or neutralize them, they have been built in vain. .The value of field defences is undoubtedly very great. They can be rapidly made in accordance with the latest tactical ideas and sited in positions found most suitable at the time. With well sited machine guns, anti-tank guns and obstacles, covered by the fire of artillery (itself protected by mobility and concealment) positions have considerable power of resistance. But it must he remembered that in 1918 when attacked by tanks and unlimited artillery ammunition, even the strongest trench lines often failed to stop an attack. After the declaration of war, time may not be available to prepare them. There are occasions when material defensive preparations in peace time will have to be made and areas held for military, political or industrial reasons. Munitions play so vital a part in modern war that the retention of certain areas of manufacture or supply may be essential. In other places, where for purely military reasons it might be wiser to withdraw and demolish the communications, public opinion may insist on a forward position being held. Again, the effect of the systematic destruction of industrial areas by an invader is now so great, that victory even cannot efface all trace of his presence. Every effort will therefore be made to fight on the enemy's ground. But to protect areas until the effect of the offensive is felt and to econo mize men so that the striking force is a maximum, some form of permanent fortification built in peace time, will at times and in certain places be required. Expense is a governing factor and new weapons and material will affect its form.

New Weapons and Material.

Of the recent innovations in weapons and material, gas and ferro-concrete have added strength to the defence. By means of gas inundations and gas shell bom bardments, the favourable lines of advance can be denied to the attackers, while the defenders, in gas-proof works supplied with pure air, are immune. The adoption of ferro-concrete for defence works adds considerably to their resistance to shell fire. Four feet of ferro-concrete is proof against 6in. shell and 6ft. will withstand bombardment by shells up to i5in. To resist overturning, how ever, the concrete must be used in large masses. When made with quick hardening aluminous cement, ferro-concrete works can be taken into use 48 hours after completion. Tanks and aircraft on the other hand, by their mobility and capacity for surprise attack, have added to the difficulties of the defence. Cross-country ar moured vehicles can attack rapidly over long distances and over any ordinary country except mountains, marshes and thick woods. They can cross wire entanglements and require special obstacles to stop them ; so that land mines, vertical faced ditches and ferro concrete blockhouses containing anti-tank guns, will be required for the defence. Aircraft compel the defenders to conceal and disperse defences to a far greater degree than formerly, and cover has to be provided against aerial bombs, which at present weigh up to 2,000 lb. The fire of super-heavy artillery, directed by air observation from railway or semi-mobile mountings, causes more damage to the fixed defences of the defender than to the attack, while by sound-ranging and flash-spotting methods the defender's guns, if in protected battery positions, and therefore limited in number, can be more easily located than those of the attacker.The devastation of areas and complete destruction of com munications is a, powerful weapon of defence. This can seldom be completely carried out in industrial areas, but in less developed countries or where communications or water supplies are restrict ed, thorough and complete demolition will cause a modern army considerable delay. The thorough demolition of a tunnel, especi ally if supplemented by the use of delay action mines, will take months to repair, and the delay caused may be greater than that effected by a barrier fort. In 1918 the destruction of the bridges, roads and railways by the retreating German armies often delayed the Allies more than their resistance ; and had the communications, in the area between Maubeuge and the Ardennes in 1914, been totally destroyed, the effect would have been far-reaching.

Future Form of Permanent Fortification.

In mountain ous countries or areas where communications are limited, barrier forts, coupled with the destruction of roads and railways, will be used. But generally fortification will take the form of zones of defence, without large permanent works. Where the flanks can be made secure, as with the Chatalja lines of Constantinople, or the Viborg isthmus of Finland, between Lake Ladoga and the Gulf, a fortified zone will have great strength. In other cases extensive zones will be used as pivots of manoeuvre, and as pro tected areas for munitions, aerodromes, centres of communication, etc., safe against attack by mechanized forces. Within these zones the fortifications will not take the form of elaborate forts, but will consist of dispersed and concealed tank proof localities, with the intervals between them well covered by obstacles and the fire of all arms. The amount of material preparation made in peace time, will vary according to the degree of readiness required, but complete and detailed plans and schemes of defence will be made out and large scale maps prepared. Arrangements will be made for communications and depots of material so that work can be carried out at short notice; and for the defence schemes to be revised periodically and brought up to date, to keep pace with modern requirements. The following factors will be considered: (a) The provision of an obstacle against a "coup de main" carried out by cross-country armoured vehicles. Waterways and inundations such as those of Fortress Holland or the Yser afford protection, while judicious afforestation would limit the lines of approach.(b) Arrangements for air defence; gun and searchlight em placements, telephonic communication, and sound-location instal lations.

(c) The provision of observation posts, command posts, ma chine and anti-tank gun positions—concealed, dispersed, pro tected by ferro-concrete or armour and connected by buried tele phone cables.

(d) Afforestation to give cover from aeroplane observation, and the control of building and planting so as to keep clear the field of fire or view.

(e) Increase of road, rail and tramway communications. (1) Landing grounds for aircraft, provided with sunken sites for hangars to minimize the lateral effect of air bombs.

(g) The selection of battery positions, organization of infantry tank proof localities, provision of obstacles, shell-proof cover in ferro-concrete shelters or deep dugouts, and subways. Arrange ments for gas proofing and the supply of pure air and electric lighting of all works, etc.

Whatever the form or degree of fortification adopted may be, one can seldom rely on the theory of complete protection, or say, like Petain at Verdun, "Ils ne passeront pas." To gain time and economize force are the objects of fortification, and the essence of defence lies in organization, concealment, observation, communication and the stout hearts of well armed men.

Since the World War France has fortified her eastern frontier with an elaborate chain of defences known as the Maginot Line. Germany is fortifying the previously demilitarized Rhineland (r 936) with a wall of modern obstacles to invasion. (E. H. K.)