Principles of Modern Field Defences

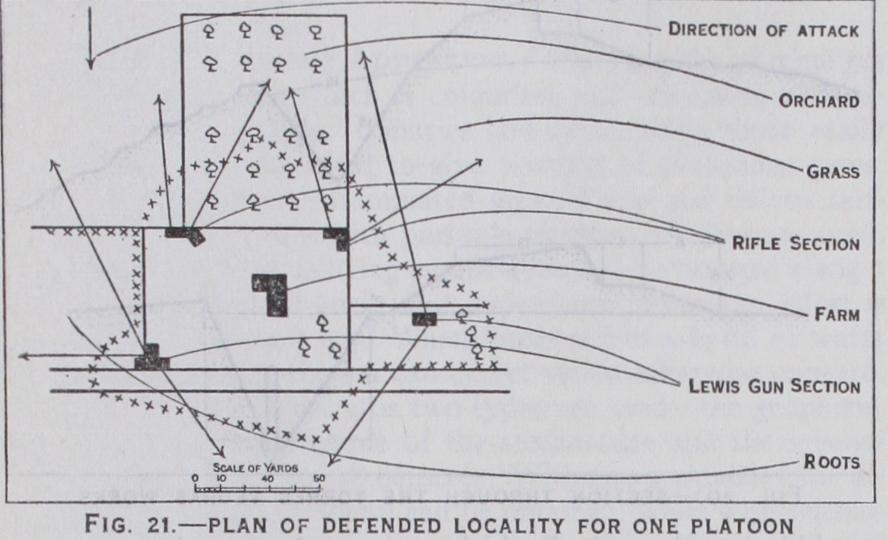

PRINCIPLES OF MODERN FIELD DEFENCES While the basic principle of hitting the enemy without being hit oneself remains unchanged, the increased efficiency of artillery and small arms and the introduction of tanks have considerably affected the design of field fortification. In early times command and an unclimbable obstacle were necessary; now observation, concealment and tank obstacles are required. The defender by skilful use of the ground, reinforced by the artificial aid of field works, can hold out against a greatly superior enemy, but protec tion is required against tanks, rifle and machine gun fire. Also, when time is available, against heavy high explosive shell, air bombs and gas. Field fortification varies from "hasty" defences made on the battlefield to "deliberate" work on rear defences. Machine guns, anti-tank guns and artillery form the framework of a defensive position. To use them to the best advantage, good observation is necessary, and as field defences seldom have suf ficient strength to protect them against heavy shells, concealment is essential. A continuous trench held throughout its length is a weak line lacking in strength and depth. Important tactical local ities, supporting one another and flanked by the fire of machine guns and artillery, are therefore held by complete infantry units. These "defended localities" are sited where possible to be proof against tank attack. They are organized as a system of "defended posts" consisting of short lengths of fire trench, dispersed in the best fire positions, and each capable of holding a section of in fantry (seven men) see fig. In order to prevent these defended posts and localities from being easily recognized on aeroplane photographs, to provide inter-communication, and to afford the intermediate fire positions required in fog or darkness, they are later connected by trenches.

Fire Trenches.

Fig. a 2 shows the normal section of a fire trench. The thickness of the parapet is sufficient to stop rifle and machine-gun bullets, as well as shrapnel and shell splinters, but no attempt is made, as in the old days, to make it proof against shell fire. To localize the effect of high explosive shells, traverses i 5f t. wide are left every 3oft. and a low parapet of earth, known as the parados, is thrown up behind the trench. To give increased protection from shell fire and to facilitate concealment, deep narrow trenches were introduced. These were satisfactorily used in the Boer War for temporary occupation in very firm soil. They were also tried in the beginning of the war of 1914-18, but it was soon found that for inter-communication and to prevent the fire trench from being entirely closed up by shells falling near it, wider trenches were necessary. However, short lengths of narrow trench, called shell slits, were found useful for cover during a sudden bombardment. Prior to 1914 loopholes and overhead cover were provided, but under modern shell fire these were rapidly destroyed, and the debris hindered men from firing over the para pet. Small and very carefully concealed loopholes for snipers and look out posts were therefore the only ones used.

Revetment and Drainage.

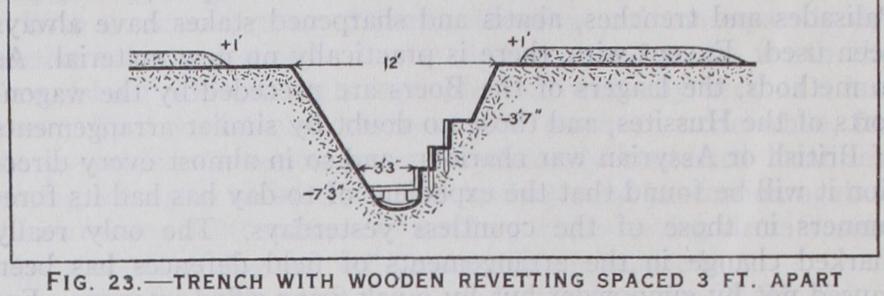

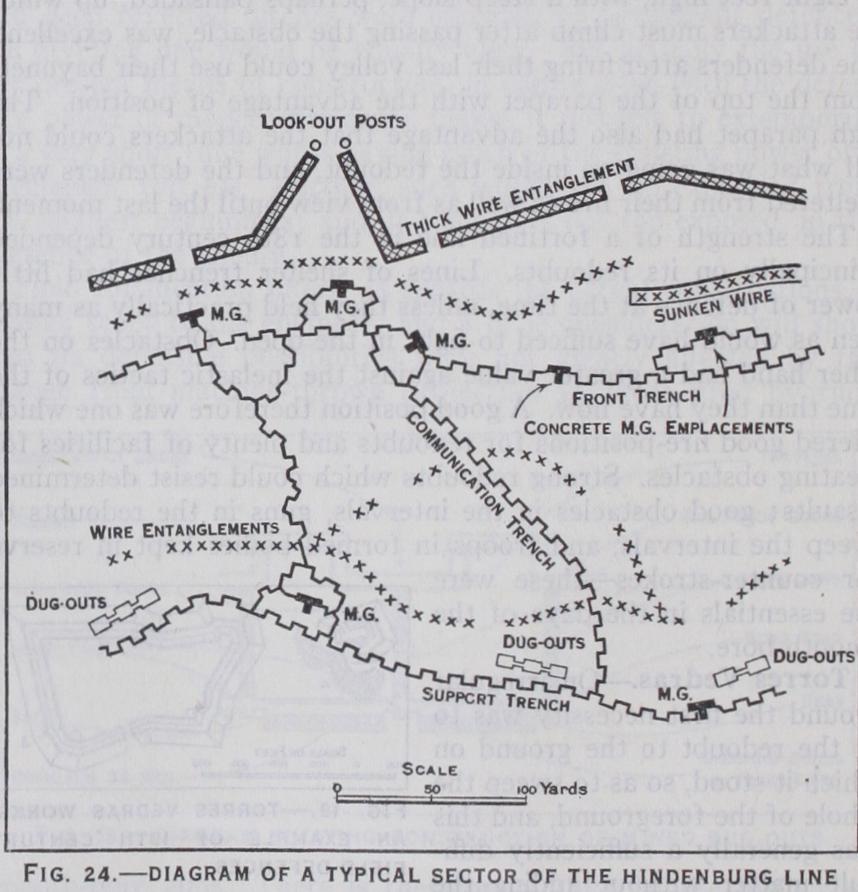

Under the action of the weather, in normal soil the sides of the trench will not stand at a steep slope. The trench must therefore either be widened at the top, at the expense of protection, and the slope lessened, or a revet ment wall provided. This consists of brushwood hurdles, corru gated iron, expanded metal, canvas and wire netting. sandbags, etc. Corrugated iron when damaged by shell fire is difficult to dig out and replace, while canvas, whether in -panels or sandbags, soon rots. The labour entailed in building the initial revetment and in its upkeep is so great that it is used as little as possible. The sec tion of the Hindenburg line (fig. 24) is a good example of a trench with gentle slopes and revetted only at the fire step. To enable trenches to be occupied in wet weather, and to prevent their col lapse, good drainage is essential. Fig. 23 shows a trench with wooden revetting or "A" frames spaced three feet apart. Trench boards are laid on the upper cross pieces and the bottom of the trench forms a drain. Where the water level is close to the surface of the ground breastworks are used in place of trenches. The time required to dig trenches naturally varies with the soil and distance marched, but 6ocu.ft. in a four hour task may be con sidered as an average rate per man. Investigations have been made at Chatham on the lines of the Industrial Fatigue Research Board to facilitate digging, and a simple drill formulated. By attending to rhythm, and working the shovel at the rate of 18 swings, alternatively with the pick at the rate of 28 strokes per minute, with rest pauses 01 two minutes in every ten, output is increased and fatigue lessened.

Siting of Fire Trenches.

In order to secure the observation so essential for artillery, anti-tank and machine-gun fire, infantry trenches are sited in advance of the observation posts. Provided that artillery and machine-gun support can be arranged, the field of fire in front of these trenches need not be more than 15oyd. ; but where hasty or temporary positions are occupied, as for out posts or rear guards, 5ooyd. is advisable. Enfilade or flanking fire is most effective. A fire trench should be so designed and sited that the occupants, while being able to use their weapons to the best advantage, are protected from the enemy's fire and tank attack. Concealment and anti-tank defence are, therefore, of great importance. In undulating or hilly country, trenches sited near the crest line have often a long field of view and fire, but they are conspicuous and are usually close to the observation post which it is one of their duties to protect. A position down the forward slope is therefore often better. When the attacker is greatly superior in artillery, and surprise can be attained, a posi tion on the reverse or rearward slope, with artillery observation and machine gun fire from a ridge in rear, has considerable ad vantages. The Hindenburg line dug by the Germans in 1916-17 between Arras and St. Quentin, is an interesting example of the siting of defences. The position was primarily chosen to secure good observation and cover for the defenders, while denying artillery positions and observation to the attack. The front line, of irregular trace to obtain full value from flanking fire, was sited where possible down the forward slope, while the support line was in rear of the crest. The position was protected by wide belts of wire, and defended by a series of ferro-concrete machine-gun emplacements 8o to 15oyd. apart sited to flank the wire obstacle.

Obstacles.

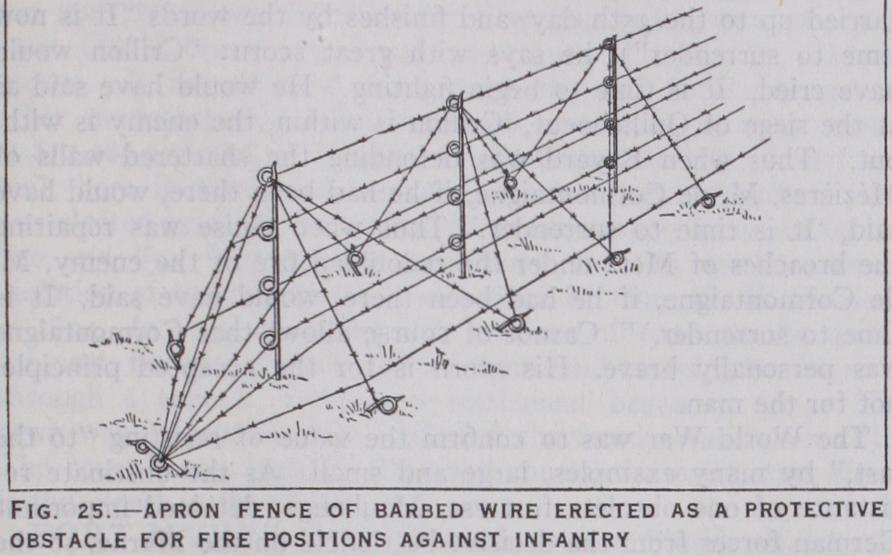

In order to delay the enemy under the fire of the defenders and to shepherd him into areas where he can be easily dealt with, protective and tactical obstacles are erected. Protec tive obstacles for the immediate protection of the fire positions, are placed 3o to rooyd. from the trenches—close enough to pre vent the enemy cutting them by night and far enough to prevent bombing by hand grenades. Tactical obstacles in large irregular blocks are sited in conjunction with the artillery and machine gun fire. Against infantry, wire entanglements are generally used. Fig. 25 shows an apron fence of barbed wire which can be erected by ten men at the rate of iooyd. an hour. Abatis made by cutting down trees or bushes three feet from the ground and inter lacing the branches with wire make good obstacles, but unless in hollows are apt to restrict the view of the defenders. Inundations are of great value.Against tanks, since artificial obstacles take considerable time and labour to erect, the greatest use is made of existing ones such as woods, marshes, waterways, steep banks, cuttings, etc. In restricted approaches, such as the entrances to villages, vertical steel girders set in concrete blocks, or "elephant pits" 8f t. deep and 1 oft. wide, lightly covered with timber and earth, are effec tive. For longer fronts a V-shaped ditch with a five foot vertical revetted face nearest the defenders will stop tanks until battered by artillery. Tank mines, however, form the best obstacles. These consist of light portable mines laid just below the surface of the ground, or may be improvised with shells with percussion fuses as shown in fig. 26.

Protection from Shell Fire and Gas.

While two feet of earth is sufficient to stop shrapnel or shell splinters, mined dugouts or ferro-concrete shelters are required for protection against heavy shell and aerial bombs. To be proof against the most dangerous shells mined dugouts must be soft. deep, but against 6in. shells Soft. of clay or 25ft. of chalk is sufficient. For ferro-concrete shelters a thickness of four feet is proof against 6in. shell and six feet will withstand 15in. For protection against gas, dugouts, con crete shelters and cellars can be provided with doors of gas proof material, or air pumps with filters installed, which will supply pure air at a higher pressure than that outside and so prevent the entry of the gas. For observation posts existing features are generally used—a platform in a tree, behind a hedge or in a house. For ma chine gun emplacements, since concealment is essential, positions blending with existing features would as far as possible be used. Fig. 27 shows a machine gun emplacement in the open. This would normally be hidden by camouflage netting. Camouflage is used to conceal important spots from air observation and pho tography. Trenches unless in woods cannot be hidden from the air, but observation posts, machine gun emplacements, gun posi tions, and headquarters, when camouflaged before occupation, and the tracks to them carefully regulated, are difficult to observe.

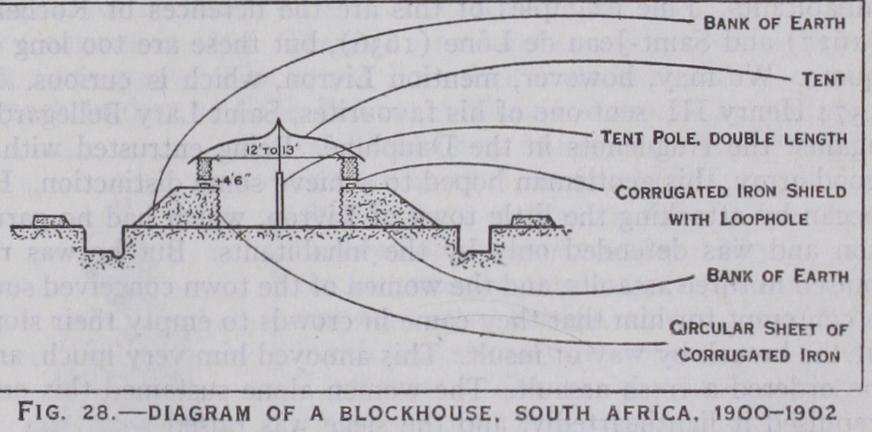

For the defence of small posts, blockhouses are frequently used. These vary from the log stockades of the Red Indian wars, stone sangars for hill pickets on the north-west frontier of India, corrugated iron and shingle blockhouses (see fig. 28) in South Africa, to the concrete "pill-box" of 1916-18. With the advent of mechanized forces, these will again be used to contain an anti tank gun for the protection of areas liable to attack by armoured fighting vehicles. (E. H. K.) In tracing the history of the science of fortification and in outlining the practice of our own time it has been necessary to dwell chiefly on the material means of defence and attack. The human element has had to be almost ignored. But here comes in the paradox, that the material means are after all the least impor tant element of defence, for the best defences recorded in history owed little to the builder's art. The splendid defence in 1667 of Candia; whose enceinte, of early Italian design, was already obso lete, but whose capture cost the Turks ioo,000 men; the three years' defence of Ostend in 16o1; the holding of Arcot by Clive, are instances that present themselves to the memory at once. The very weight of the odds against them sometimes calls out the best qualities of the defenders; and the man when at his best is worth many times more than the rampart behind which he fights. But it would be a poor dependence deliberately to make a place weak in order to evoke these qualities. One cannot be sure that the garrison will rise to the occasion, and the weakness of the place has very often been found an excuse for giving it up with little or no resistance. Very much depends on the governor. Hence the French saying, "tant vaut 1'homme, tant vaut la place." Among modern men we think of Todleben (not governor, but the soul of the defence) at Sevastopol, Fenwick Williams at Kars, Denfert Rochereau at Belfort and Osman Pasha at Plevna. The sieges of the 16th and i7th centuries offer many instances in which the event turned absolutely on the personal qualities of the governor; in some cases distinguished by courage, skill and foresight, in others by incapacity, cowardice or treachery. The reader is re ferred to Carnot's Defense des places fortes for a most interest ing summary of such cases, one or two of which are quoted below.

In 1645 the young governor of the royal post at Bletchingdon House was entertaining a party of ladies from Oxford, when Cromwell appeared and summoned him to surrender. The attack ing force had no firearm more powerful than a carbine, but the governor, overawed by Cromwell's personality, yielded. Charles I., who was usually merciful to his officers, caused this governor to be shot. A defence of another kind was that of Quilleboeuf in 1S92. Henry IV. had occupied it and ordered it to be fortified. Before the works had been well begun, Mayenne sent 5,00o men to retake it. Bellegarde undertook its defence, with 115 soldiers, 45 gentlemen and a few inhabitants. He had ammunition but not much provisions. With these forces and a line of defence a league in length, he sustained a siege, beat off an assault on the 17th day and was relieved immediately afterwards. The relieving forces were astonished to find that he had been defending not a fortified town but a village, with a ditch which, in the places where it had begun, measured no more than four feet wide and deep.

Sometimes the ardour of defence inspired the whole body of the inhabitants. Fine examples of this are the defences of Rochelle (1627) and Saint-Jean de Lone (1636), but these are too long to quote. We may, however, mention Livron, which is curious. In 1574 Henry III. sent one of his favourites, Saint Lary Bellegarde, against the Huguenots in the Dauphine. Being entrusted with a good army, this gentleman hoped to achieve some distinction. He began by attacking the little town of Livron, which had no garri son and was defended only by the inhabitants. But he was re pulsed in three assaults, and the women of the town conceived such a contempt for him that they came in crowds to empty their slops at the breach by way of insult. This annoyed him very much, and he ordered a fresh assault. The women alone sustained this one, repulsed it lightheartedly, and the siege was raised.

Arcot.—The history of siege warfare has more in it of human interest than any other branch of military history. It is full of the personal element, of the nobility of human endurance and of dramatic surprises. And more than any battles in the open field, it shows the great results of the courage of men fighting at bay. Think of Clive at Arcot. With four officers, 120 Europeans and 200 sepoys, with two i8-pounders and eight lighter guns, he held the fort against 15o Europeans and some 1 o.000 native troops. "The fort" (says Orme) "seemed little capable of sustaining the impending siege. Its extent was more than a mile in circumfer ence. The walls were in many places ruinous ; the rampart too narrow to admit the firing of artillery; the parapet low and slightly built ; several of the towers were decayed, and none of them cap able of receiving more than one piece of cannon ; the ditch was in most places fordable, in others dry and in some choked up," etc. These feeble ramparts were commanded almost everywhere by the enemy's musketry from the houses of the city outside the fort, so that the defenders were hardly able to show themselves without being hit, and much loss was suffered in this way. Yet with his tiny garrison, which numbered about one man for every seven yards of the enclosure, Clive sustained a siege of 5o days, ending with a really severe assault on two large open breaches, which was repulsed, and after which the enemy hastily decamped.

Clive's defence of the breaches, which by all the then accepted rules of war were untenable, brings us to another point which has been already mentioned, namely, that a garrison might honourably make terms when there was an open breach in their main line of defence. This is a question upon which Carnot delivers himself very strongly in endeavouring to impress upon French officers the necessity of defence to the last moment. Speaking of Cormon taigne's imaginary Journal of the Attack of a Fortress (which is carried up to the 35th day, and finishes by the words "It is now time to surrender"), he says with great Scorn: "Crillon would have cried, `It is time to begin fighting.' He would have said as at the siege of Quilleboeuf, `Crillon is within, the enemy is with out.' Thus when Bayard was defending the shattered walls of Mezieres, M. de Cormontaigne, if he had been there, would have said, `It is time to surrender.' Thus when Guise was repairing the breaches of Metz under the redoubled fire of the enemy, M. de Cormontaigne, if he had been there, would have said, `It is time to surrender.' " Carnot of course allows that Cormontaigne was personally brave. His scorn is for the accepted principle, not for the man.

The World War was to confirm the value of resisting "to the last," by many examples, large and small. As the obstinate re sistance of one obsolete fortress, Maubeuge, detained important German forces from the decisive battlefield on the Marne, so the fortitude of the defenders of small posts and localities repeatedly dammed the free flow of the attacker's resources and so helped to prevent a threatened disastrous break-through. Other examples are the German defence of Flesquieres, Nov. 20, 1917, against the British offensive towards Cambrai, and the British resistance in face of the German offensives in March and April 1918.