The Attack of Fortresses

THE ATTACK OF FORTRESSES In considering the history of siegecraft since the introduction of gunpowder, there are three main lines of development to fol low, viz., the gradually increasing power of artillery, the systema tizing of the works of attack and in recent times the change that has been brought about by the effect of modern small-arm fire.

Cannon appear to have been first used in sieges as mortars, to destroy hoardings by throwing round stones and barrels of burn ing composition. Early in the 15th century we find cannon throw ing metal balls, not only against hoardings and battlements, but also to breach the bases of the walls. It was only possible to work the guns very slowly, and archers or crossbowmen were needed in support of them, to drive the defenders from the crenellations or loopholes of the battlements. At that period the artillery was used in place of the mediaeval siege engines and in much the same manner. The guns of the defence were inaccurate and in capable of adequate depression so that the besieger could place his guns close to the walls, with only the protection of a few large gabions filled with earth, set up on the ground on either side of the muzzle.

In the course of the 15th century the power of artillery was largely increased, so that walls and gates were destroyed by it in an astonishingly short time. Three results shortly followed. The guns of the defence having gained equally in effectiveness, greater protection was needed for the attack batteries; bastions and outworks were introduced to keep the besieger at a distance from the inner walls; and the walls were sunk in ditches so that they could only be breached by batteries placed on the edge of the glacis. Early in the i6th century fortresses were being remod elled on these lines, and the difficulties of the attack were at once increased. The tendency of the assailants was still to make for the curtain, which had always been considered the weak point ; but the besiegers now found that they had to bring their guns right up to the edge of the ditch before they could make a breach, and in doing so had to pass over ground which was covered by the converging fire from the faces of the bastions. Towards the end of the century the attack of the curtain was still more delayed and the cross-fire over the ground in front increased by the in troduction of ravelins.

Siegecraft Before Vauban.

Gradually the whole problem of siege work centred round the artillery. The besiegers found that they had first to bring up enough guns to overpower those of the defence; then to advance their guns to positions from which they could breach the walls ; and throughout these opera tions to protect them against sorties. Breaches once made, the assault could follow on the old lines. The natural solution of the difficulty of approach to the battery positions was the use of trenches. The Turks were the first to make systematic use of them, having probably inherited the idea from the Eastern em pire. The soldiers of Western Europe, however, strongly dis liked digging, and the difficulty was dealt with in a manner remi niscent of the feudal ages, by impressing large bodies of peasantry as workmen whenever a siege was in contemplation. Through the i6th and most of the 17th century, therefore, we find the attack being conducted by means of trenches leading to the batteries, and supported by redoubts often called "places of arms" also made by trench work. During this period the result of a siege was always doubtful. Both trenches and batteries were arranged more or less at haphazard without any definite plan; and naturally it often hap pened that offensive action by the besieged against the trenches would disorder the attack and at times delay it indefinitely.Another weak point about the attack was that after the escarp walls had been strengthened to resist artillery fire as has been described, there was no clear idea as to how they should be breached. The usual process was merely an indiscriminate pound ing from batteries established on the crest of the glacis. Thus there were cases of sieges being abandoned after they had been carried as far as the attempt to breach. It is in no way strange that this want of method should have characterized the attack for two centuries after artillery had begun to assert its power. At the outset many new ideas had to be assimilated. Guns were gradually growing in power ; sieges were conducted under all sorts of conditions, sometimes against mediaeval castles, sometimes against various and widely differing examples of the new fortifi cation; and the military systems of the time were not favourable to the evolution of method. It is the special feature of Vauban's practical genius for siege warfare that he introduced order into this chaos and made the issue of a siege, under normal condi tions, a mere matter of time, usually a very short time.

Vauban's Teaching.

The whole of Vauban's teaching and practice cannot be condensed into the limits of this article, but special reference must be made to several points. The most im portant of these is his general arrangement of the attack. The ultimate object of the attack works was to make a breach for the assaulting columns. To do this it was necessary to establish breaching batteries on the crest of the glacis ; and before this could be done it was necessary to overpower the enemy's artillery. In Vauban's day the effective range of guns was 600 to 700 yards. The first object of the attack, therefore, after the preliminary operations of investment, etc., had been completed, was to estab lish batteries within 600 or 7ooyd. of the place, to counter-batter or enfilade all the faces bearing on the front of attack; and to protect these batteries against sorties. After the artillery of the defences had been subdued—if it could not be absolutely silenced —it was necessary to push trenches to the front so that guns might be conveyed to the breaching positions and emplaced there in batteries. Throughout these processes it was necessary to protect the working parties and the batteries against sorties.For this purpose Vauban devised the Places d'armes or lignes paralleles. He tells us that they were first used in 1673 at the siege of Maestricht, where he conducted the attack, and which was captured in 13 days after the opening of the trenches. The object of these parallels was to provide successive positions for the guard of the trenches, where they could be at hand to repel sorties. The latter were most commonly directed against the trenches and batteries, to destroy them and drive out the working parties. The most vulnerable points were the heads of the ap proach trenches. It was necessary, therefore, that the guard of the trenches should be in a position to reach the heads of the approaches more quickly than the besieged could do so from the covered way. This was provided for as follows. The first par allel was usually established at about 600yd. from the place, this being considered the limiting range of action of a sortie. The parallel was a trench 12 to 15ft. wide and 3ft. deep, the excavated earth being thrown forward to make a parapet three or four feet high. In front of the first parallel and close to it were placed the batteries of the "first artillery position." While these batteries were engaged in silencing the enemy's artillery, for which purpose most of them were placed in pro longation of the faces of the fortress so as to enfilade them, the "approach trenches" were being pushed forward. The normal sector of attack included a couple of bastions and the ravelin be tween, with such faces of the fortress as could support them ; and the approach trenches (usually three sets) were directed on the capitals of the bastions and ravelin, advancing in a zigzag so ar ranged that the prolongations of the trenches always fell clear of the fortress and could not be enfiladed.

Fig. 12, taken from Vauban's Attack and Defence of Places, shows clearly the arrangement of trenches and batteries.

After the approach trenches had been carried forward nearly half-way to the most advanced points of the covered way, the "second parallel" was constructed, and again the approach trenches were pushed forward. Midway between the second par allel and the covered way, short branches called demi-parallels were thrown out to either flank of the attacks ; and finally at the foot of the glacis came the third parallel. Thus there was always a secure position for a sufficient guard of the trenches. Upon an alarm the working parties could fall back and the guard would advance. Trenches were either made by common trenchwork, flying trenchwork or sap. In the first two a considerable length of trench was excavated at one time by a large working party extended along the trench: flying trenchwork (formerly known as flying sap) being distinguished from common trenchwork by the use of gabions, by the help of which protection could be more quickly obtained. Both these kinds of trenchwork were com menced at night, the position of the trench having been previously marked out by tape. The "tasks" or quantities of earth to be excavated by each man were so calculated that by daybreak the trench would afford a fair amount of cover. Flying trenchwork was generally used for the second parallel and its approaches, and as far beyond it as possible. In proportion as the attack drew nearer to the covered way, the fire of the defenders' small arms and surviving artillery naturally grew more effective, and it became necessary before reaching the third parallel to have recourse to sap.

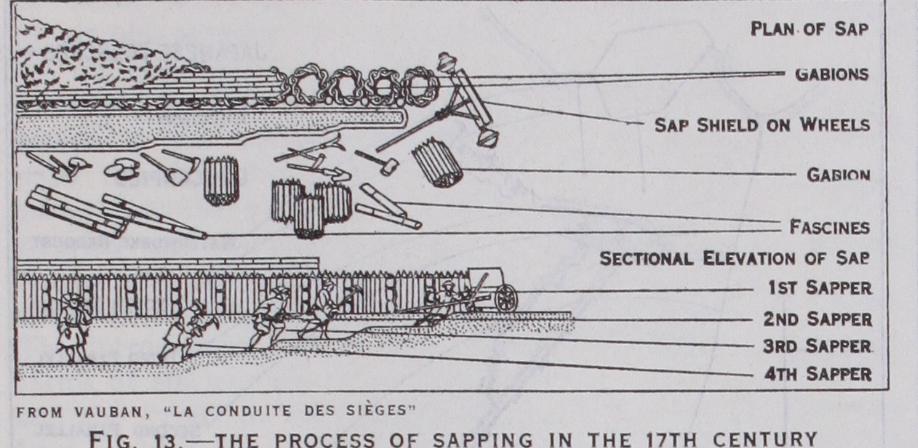

Sapping required trained men. It consisted in gradually push ing forward the end of a narrow trench in the desired direction. At the sap-head was a squad of sappers. The leading man excavated a trench one foot six inches wide and deep. To protect the head of the trench he had a shield on wheels, under cover of which he placed the gabions in position one of ter another as the sap-head progressed. Other men following strengthened the para pet with fascines, and increased the trench to a depth of three feet, and a width of two feet six inches to three feet. Fig. 13, taken from Vauban's treatise on the attack, shows the process clearly. The sap could then be widened to ordinary trench di mensions by infantry working parties.

As the work at the sap-head was very dangerous, Vauban en couraged his sappers by paying them on the spot at piecework rates, which increased rapidly in proportion to the risk. He reck oned on a rate of progress for an ordinary sap of about 5oyd. in hours.

The nearer the approaches drew to the covered way, the more oblique became the zigzags, so that little forward progress was made in proportion to the length of the trench. The approaches were then carried straight to the front, by means of the "double sap," which consisted of two single saps worked together with a parapet on each side. To protect these from being enfiladed from the front, traverses had to be left at intervals.

From the third parallel the attack was pushed forward up the glacis by means of the double sap. It was then pushed right and left along the glacis, a little distance from the crest of the covered way. This was called "crowning" the covered way, and on the position thus gained breaching batteries were established in full view of the escarp. While the escarp was being breached, if it was intended to use a wide systematic attack, a mine gallery (see "Military Mining" below) was driven under the covered way and an opening made through the counter-scarp into the ditch. The sap was then pushed across the ditch, and if necessary up to the breach, the defenders' resistance being kept under by mus ketry and artillery fire from the covered way. The ravelin and bastions were thus captured successively.

Vauban showed how to breach the escarp with the least ex penditure of ammunition. This was done by making, with succes sive shots placed close together (as was feasible even then at such short range) horizontal and vertical cuts through the revetment wall. The portion of revetment enclosed by the cuts being thus detached from support was overturned by the pressure of the earth from the rampart. Ricochet fire was also the invention of Vauban. He showed how, in enfilading the face of a work, by using greatly reduced charges a shot could be made to drop over the crest of the parapet and skim along the terreplein, dismount ing guns and killing men as it went.

18th Century Principles of Defence.

The constant suc cess of Vauban must be ascribed to method and thorough or ganization. There was a deadly certainty about his system that gave rise to the saying "Place assiegee, place prise." He left nothing to chance, and preferred as a rule the slow and certain progress of saps across the ditch and up the breach to the loss and delay that might follow an unsuccessful assault. His con temporary and nearest rival Coehoorn tried to shorten sieges by heavy artillery fire and attacks across the open; but in the long run his sieges were slower than Vauban's. The theory of defence at this time appeared to be that as it was impossible to arrest the now methodical and protected progress of the besiegers' trenches, no real resistance was possible until after they had reached the covered way, and this idea is at the root of the ex traordinary complications of outworks and multiplied lines of ramparts that characterized the "systems" of this period. No doubt if a successor to Vauban could have brought the same genius to bear on the actual defence of places as he did on the attack, he would have discovered that the essence of successful defence lay in offensive action outside the body of the place, viz., with trench against trench. Fighting was so much regulated by the laws and customs of war that men thought nothing of giving up a place if, according to accepted opinion, the enemy had advanced so far that they could no longer hope to defend it suc cessfully. This is the real reason for the feeble resistance so often made by fortresses in the 17th and i8th centuries, which has been attributed to inherent weakness in fortifications. Custom exacted that a commandant should not give up a place until there was an open breach or, perhaps, until he had stood at least one assault. Even Napoleon recognized this limitation of the powers of de fence when in the later years of his reign he was trying to im press upon his governors the importance of their charge. The limi tation was unnecessary, for history at that time could have afforded plenty of instances of places that had been successfully defended for many months of ter breaches were opened, and as sault after assault repulsed on the same breach. But the same soldiers of the 17th and i8th centuries who had created this ar tificial condition of affairs, established it by making it an under stood thing that a garrison which surrendered without giving too much trouble after a breach had been opened should have hon ourable consideration ; while if they put the besiegers to the pains of storming the breach, they were liable to be put to the sword.

Peninsular War.

It has been necessary to dwell at some length on the siegecraft of Vauban and his time, not merely for its historical interest, but because the system he introduced was practically unaltered until the end of the r 9th century. The sieges of the Peninsular War were conducted on his lines ; so was that of Antwerp in 183o; and as far as the disposition of siege trenches was concerned, the same system remained in the Crimea, the Franco-German War and the Russo-Turkish War. The sieges in the Napoleonic wars were few, except in the Iberian peninsula. These last differed from those of the Vauban period and the i8th century in this, that instead of being deliberately undertaken with ample means, against fortresses that answered to the requirements of the time, they were attempted with inade quate forces and materials, against out-of-date works. The fortresses that Wellington besieged in Spain had rudimentary outworks, and escarps that could be seen and breached from a dis tance. At that time, though the power of small arms had in creased very slightly since the last century, there had been a distinct improvement in artillery, so that it was possible to breach a visible revetment at ranges from 500 to 1,000 yards. Welling ton was very badly off for engineers, siege artillery and material. Trench works could only be carried out on a small scale and slowly. Time being usually of great importance, as in the first two sieges of Badajoz, his technical advisers endeavoured to shorten sieges by breaching the escarp from a distance—a new departure —and launching assaults from trenches that had not reached the covered way. Under these circumstances the direct attacks on breaches failed several times, with great loss of life.

Crimea.

During the long peace that followed the Napoleonic wars, one advance was made in siegecraft. In England in 1824 successful experiments were carried out in breaching an unseen wall by curved or indirect fire from howitzers. At Antwerp in 183o the increasing power and range of artillery, and especially of howitzers, were used for bombarding purposes, the breaches there being mostly made by mines. Then came one of the world's great sieges; that of Sevastopol in (see CRIMEAN WAR). The outstanding lesson of Sevastopol is the value of an active defence; of going out to meet the besieger, with counter-trench and counter-mine. This Iesson increased in value in proportion to the increased power of the rifle.In comparing the resistance made behind the earthworks of Sevastopol with the recorded defences of permanent works, it is essential to remember that the conditions there were abnormal.

The siege corps was not sufficiently strong to invest the fortress completely, in fact the Russians came nearer to investing the Allies ; the Russians had the preponderance in guns almost throughout ; the Russian force in and about Sevastopol was nu merically superior to that of the Allies. We must add to this that Todleben had been able to get rid of most of his civilian pop ulation, and those who remained were chiefly dockyard workmen, able to give most valuable assistance on the defence works. The circumstances were therefore exceptionally favourable to an active defence. The weak point about the extemporized earthworks, which eventually led to the fall of the place, was the want of good bomb-proof cover near the parapets.