The Modern Fur Trade

THE MODERN FUR TRADE Sources of Supply.—It is a mistake to suppose that furs are the product only of cold climates. The fur trade draws its supplies from all over the world, and finds use for those of the tropics as well as for those of the Arctic. But it remains a fact that the more valuable pelts are mostly obtained from those regions where the winter temperature is sufficiently low to ensure the growth of thick and luxuriant fur. Canada and North America generally, northern Europe and Siberia are therefore the most important sources of fur supply, and their production in this kind includes almost all the so-called "fine furs," and the majority of those classed as staple articles.

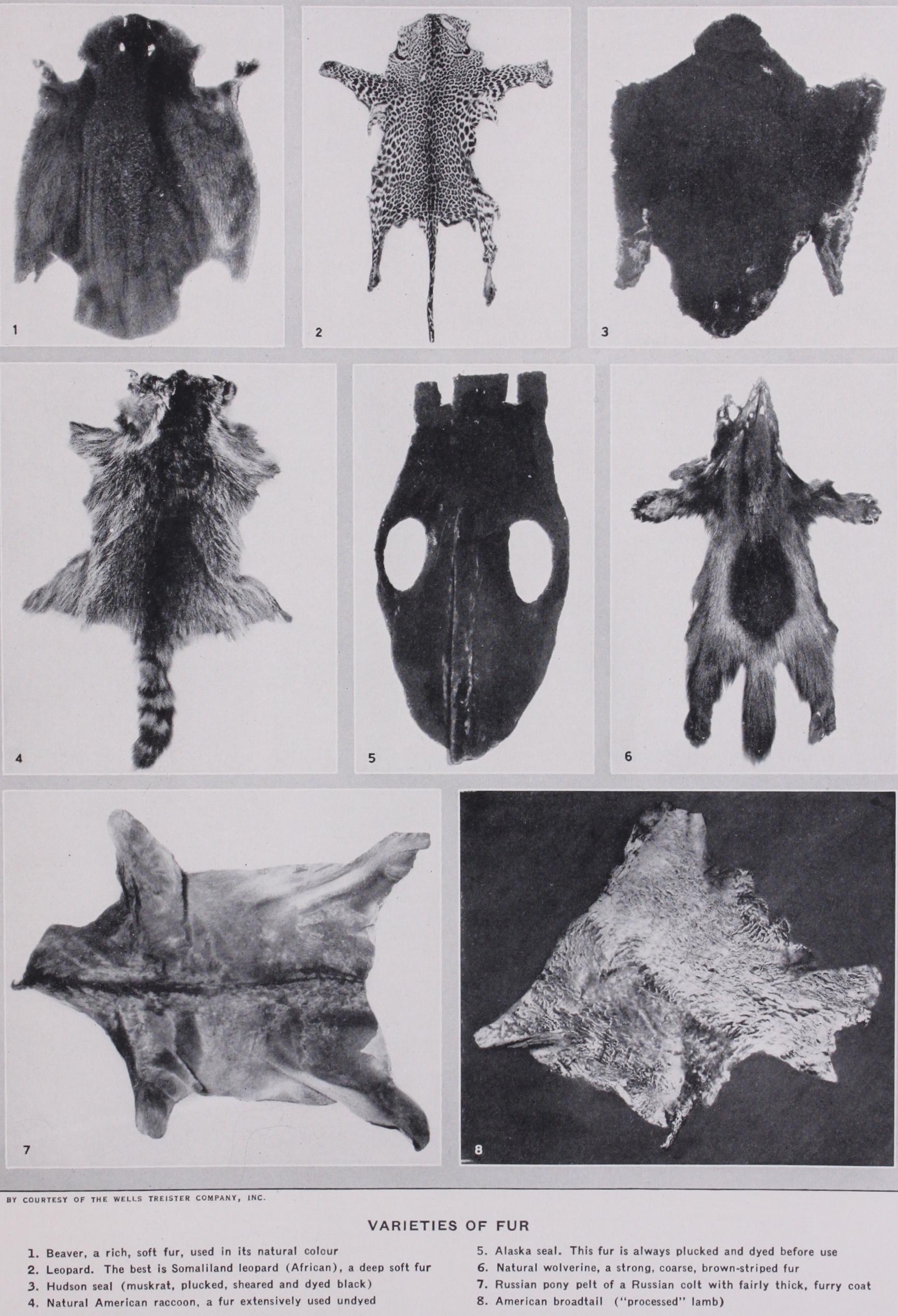

The principal furs obtained from North America are beaver, musquash, skunk, American opossum, mink, marten, fisher, er mine, silver fox, blue fox, red fox, white fox, cross fox, seal, raccoon, white bear, grizzly bear, wolf, lynx and wolverine. Of these seal, raccoon, musquash, opossum, mink, skunk, beaver and the various kinds of foxes are the most important commercially.

Northern and central Europe and Siberia provide squirrel, Rus sian sable, ermine, red fox, cross fox, white fox, wolf, bear, badger, kolinsky, mink, marmot, fitch, stone marten, baum marten, otter and a certain amount of musquash. The chief contribution of the British Isles to the list of wild fur supplies is moleskin, of which the best grades come from Scotland. The British Isles also pro duce wild rabbit and a few otter, wild cat and stoat. Moleskin is also obtained from Holland, France and parts of Africa.

China supplies marmot, kid, goat, lamb, moufflon, etc. ; and central Asia, Persian lamb and other lambskins. The principal Australian furs are Australian opossum, red fox, wallaby and rab bit. New Zealand also produces opossums and a large number of rabbit skins. The Australian and New Zealand rabbit skin supply is a factor of great and increasing importance in the fur trade.

From South America come nutria, chinchilla (though this fur is scarce) foxes, skunk, chinchilla rats, etc. The fur production of Africa is relatively unimportant in the commercial sense. The skins of various animals of the deer tribe are obtained from there, together with monkey, panther, lion, otter and hyrax. Of the minor fur producing regions, Japan produces a certain amount of mink and flying squirrel; India, red foxes, tiger and some stone marten ; the Balkans, lambskins, fox, martens, etc. ; and Italy and Spain, lambskins.

The seal is the principal marine animal whose fur is used in the fur trade, the best skins being obtained from the north Pacific, and particularly from the coast and islands of Alaska. The Alaskan seal herds are protected by an international convention, and since it has been in force their total has increased from under i oo,000 to over 800,000. Sealskins are also obtained off the Cape of Good Hope and in the north and south Atlantic. Sea otter, another marine animal with a valuable pelt, is rare ; the best specimens live in Alaskan and Canadian waters but are strictly protected.

Collection and Distribution.—Fur skins find their way to the world's markets through two channels. A large number, after being delivered or sold by the trappers to collecting agents, are bought by the representatives of skin merchants in various centres, and pass directly into use. The majority of the world's catch however is consigned to agents or brokers for sale at one or other of the great public fur auctions held periodically in cer tain centres. The most important of these auctions are those at London, Leipzig and New York, while Montreal, St. Louis (the Alaska seal catch is sold here), Paris, Winnipeg, Copenhagen, Seattle, Edmonton, etc., are fur auction centres of secondary im portance. In London, which, from the number and value of the furs sold there, is the chief distributing centre for the world's fur trade, public auctions of skins are held three times a year—in January, April and October—each series lasting from three to four weeks. The offering is made up of (I) fur skins consigned from all parts of the world to about half -a-dozen firms of fur brokers; and (2) the collection of the Hudson's Bay Company. The latter is sold separately by the company, but the other brokers group their collection into sections, including seal skins and Aus tralian furs, Chinese and Japanese furs, and the main catalogue, which comprises furs from North America, Europe, etc., and is the most important part of the sale. Each broker firm sells its own col lection, the order of selling being arranged by lot. The offerings in each section, either in bulk or in sample, are open to inspection in various warehouses several days before the auctions commence, and buying in the sale room is done from the catalogue, no lots or samples being shown there. The same procedure as regards in spection and buying is followed at the other fur auction centres, though selling arrangements may vary. In New York there are three major public fur auctions a year, in addition to minor auc tions each month at certain periods of the year; and this system also prevails at Leipzig. The New York auctions, though they include furs from all parts of the world, are mainly concerned with American skins ; those at Montreal almost entirely so. The Paris and Winnipeg auctions are only of local collections, and at Copenhagen there is annually held a sale of Greenland furs.

The Leipzig auctions are of especial importance in connection with Russian furs, for which they provide one of the principal markets. Under the Soviet Government in Russia, the export trade in furs is a state monopoly, and in theory the Russian fur catch is collected by certain state trading organizations which pay the trappers an officially fixed price for the skins. This price, however, is seldom the highest obtainable, and a good deal of private trading, with subsequent smuggling of furs over the fron tiers into China and elsewhere, goes on. Nevertheless the greater part of the catch comes eventually into the hands of the appropri ate authority, and whatever proportion of it is deemed surplus to domestic requirements is held for export and sold abroad at a convenient time for the account of the Soviet Government.

Buyers from all parts of the world attend the fur auctions in London and Leipzig, the great majority of them being either skin merchants, fur brokers and commission agents or manufac turing furriers. The fur broker buys and sells on commission terms for his clients, while the skin merchant buys for his own stock the kinds of furs for which he anticipates a demand. Each class of trader is of necessity an expert in raw furs, and the skin merchant can tell not only the exact grade and value of a skin, but often the precise district of its country of origin.

The approximate quantities of certain of the more important furs offered at the London auctions during the year 1927 were as follow: Beaver 51,631, musquash 490,558, red fox 625,198, skunk 1,660,161, Australian opossum 1,677,507, mole 1,961,443, squirrel 3,203,317, fur seals 22,866, American opossum Persian lamb 970,300, marmot 558,486, nutria 31,211, cross fox 17,270, white hare 1,084,590, mink 120,563, Russian ermine 213,708, stone marten 39,347. With these figures may be compared some for 1913, as follows: Red fox 96,395, musquash 3,861,010, Australian opossum 275,600, skunk 863,638, beaver 23,070, fur seal 15,183, mole 1,445,124, squirrel 628,177. Price comparisons have little real significance because fur skins are susceptible of such numer ous variations in quality that a common basis is difficult to find. The following, however, are of interest : the figures given are as a rule the highest price paid for a single skin in the auctions of the year in question: Red fox-1913, £5, 1927, £12.5s.; musquash 1913, 4s.6d., 1927, Australian opossum—I 913, 6s., 1927, 38s.; beaver-1913, f3.8s., 1927, f13; skunk-1913, 35s.6d., 1927, I 2S.

Auctions of Australian and New Zealand rabbit skins are held in London about six times a year, the offerings including both furriers' and hatters' skins. The total export of rabbit skins from Australia during the fiscal year 1925-26 was 15,028,304 lb., valued at £2,880,360, of which 5,117,458 lb. were consigned to the United Kingdom and 9,270,118 lb. to the United States of America. During the calendar year 1912 the total export was 9,856,034 lb., valued at £577,050, the United Kingdom receiving 6,034,532 lb. and the United States 1,842,052 lb. The United States imported in 1927, 22,069,111 lb. of rabbit, hare and coney skins. The total imports and manufactures of fur for 1926 were for The total exports for 1926 were $23,215, and for 1927, $30,892,985.

Fur Dressing and Fur Dyeing.—Briefly, the function of the fur skin dresser is to make the skin suitable for use in the later stages of the trade, the objects aimed at being the creation of a soft, pliable leather; the removal of superfluous matter from the pelt ; and the preservation and enhancement of the natural lustre of the fur. The details of the process vary widely with the nature and condition of the skin treated, but in every instance there are at least four distinct stages, some being comprised of several processes, in the operation. First of all there is the prelim inary cleaning and softening of the pelt ; then "fleshing" (removal of fleshy matter from the skin) and stretching ; then "leathering" (the formation of a leather on the skin, actually a form of tan ning) ; and then a final cleaning. After each stage, and between many of the intermediate processes, the fur is cleaned, a revolving wooden drum containing sawdust or other suitable material being generally used for this. Separate departments of the fur dresser's art are "unhairing" (the removal of guard-hairs where necessary), shaving, etc. ; while the dressing of seal skins is a complicated business presenting features not found in the majority of furs. Though it doubtless originated in a primitive and haphazard manner, modern fur skin dressing is a highly developed scientific process requiring, incidentally, a considerable mechanical equip ment.

Fur dyeing is of great antiquity, but may be said to date its modern development from the latter part of the i9th century. Before that date the dyeing of furs was mainly carried out with vegetable or mineral colouring matters. Since then, however, various chemical compounds known as fur bases have come into general use, and have largely superseded the older materials by reason mainly of the ease with which they can be applied. The use of these synthetic compounds has also enabled fur dyers to produce many new colours on furs, and fresh ones are added every year. This again has led to the adoption by the fur trade of many skins which in their natural colours would be disdained by the public, but which when well dressed and dyed make most attractive furs. Chief among these is rabbit, which, under its trade name of coney, appears in almost innumerable shades, and is one of the most important furs in the world. From the cheap ness of the skin, dyeing in this instance has brought furs within the reach of millions who could not otherwise afford them. Another result of the development of fur dyeing is that the public is enabled to obtain excellent substitutes for furs which are scarce or costly. Thus, marmot is dyed to represent the valuable mink, while dyed musquash is widely used in the place of sealskin. The technical side of fur dyeing is a matter upon which great secrecy is maintained. Each dyer has his own proc esses which are jealously guarded, and though he may achieve the same results as his neighbour it is often by means which are to a large extent different. Leipzig is the chief fur dyeing centre of Europe, a position it owes partly to the skill of its workers, but largely to the success of the German chemists in producing dyestuffs. France and Belgium annually dye millions of imported and domestic rabbit skins, and there is a flourishing fur dyeing industry in London which has long been reputed for the excellence of its dyes on sealskins. The fur dyeing industry of New York, a large and prosperous one, received a great impetus from the cessation of the supply of Leipzig-dyed furs during the war of 1914-18, and has since developed rapidly.

Fur Manufacturing.

Furriery, or the making-up of furs into garments, has progressed from the primitive sewing together of skins to the position of a highly skilled and intricate occupa tion, and the modern manufacturing furrier often has a good claim to be recognized as an artist in the same sense in which a designer and creator of gowns is so recognized. Design, indeed, plays a large part in furriery, for there are fashions in furs as there are in other articles of dress, a fact which assumes especial importance when it is remembered that fur, from being a mas culine prerogative in mediaeval times, has become an almost ex clusively feminine article of attire. Paris is the originating centre of most fur fashions, but valuable ideas often come from Vienna, while New York has developed a tradition of its own in fur design. London furriers usually modify Parisian designs to suit their own public. The skill of the manufacturing furrier is exemplified not only in the coat, cloak, stole, tie or other article he produces, but also in the economical use and tasteful combination of the skins that go to make it. The setting of the skins, that is to say, the position of each skin in the garment in relation to its neigh bours and to the garment as a whole, is another part of the furrier's work in which there is much scope for taste and ingenuity. The furrier's chief workman is the fur cutter, whose duty it is so to cut the skins for each article that the best possible use is made of them with a minimum of wastage. This is a manual oper ation for which no adequate machinery exists. The working to gether of furs is done with specially-made sewing machines, usually power driven. Though this operation calls for less skill than fur cutting it is one upon the proper performance of which the appear ance and value of the garment depends. In a skilfully sewn fur coat it is generally impossible to detect the seams without blow ing the fur apart. Manufacturing furriers may be classified in three groups. Wholesale manufacturing furriers sell the article they make to wholesale distributing houses or to retail firms; retail manufacturing furriers sell the work they do in their own shops ; and in Great Britain chambermasters undertake work for other manufacturing furriers who may find it difficult or incon venient to do it in their own workrooms.According to the Census of Production for 1924, the total value of the goods made and the work done by the fur trade in Great Britain in that year was £6,562,000, as compared with £1,658,000 in 1907. Of the 1924 figure £5,328,000 represented the selling value of made-up fur goods other than mats and rugs ; alterations and repairs to fur goods accounted for £443,000; while the amount received by fur dressers and dyers for work done for the trade was £521,000. Each of these figures is considerably above that for 1907, the most notable increase being in the amount received for alterations and repairs, which was only £21,000 in the earlier year.

The Fur Retailer.

The retail branch of the fur trade is the only one with which the public usually comes into direct contact, its function being the sale of fur garments and articles to who ever wishes to buy them. Many fur retailers also undertake to have coats, etc., repaired and remodelled for their customers. Much of the retail business in furs passes through the hands of the drapery and costume trades, but there are also many con cerns exclusively interested in the sale of furs. The fur retailer, unless a retail manufacturer, obtains his supplies from the whole sale houses or from manufacturing furriers, and his business is to some extent a seasonal one. The tendency is, however, for its seasonal nature to become less evident owing to the development of a trade in furs suitable for summer wear. It is mainly in con nection with their sale to the public that the question of the description of furs arises. The fur trade, using a large variety of skins with many of which the general public is unacquainted, is one in which deception of the purchaser is peculiarly easy; and to protect the public from this certain rules in regard to descrip tions have been laid down by the trade associations in most centres. Under the American rules, to describe a fur, the correct name of the fur must be the last word of the description; and if any dye or blend is used to give it the appearance of another fur, the word "dyed" or "blended" must be inserted between the name signifying the fur that is imitated and the true name of the fur, as : "Seal-Dyed Muskrat," or "Mink-Dyed Marmot." All furs shaded, blended, tipped, dyed or pointed, must be de scribed as such ; as, "Black-Dyed Fox," or "Pointed Fox." Also where the name of any country or district is used, it must be the actual country of the origin of the fur, as, "American Opossum." When the name of a country or place is used to designate a colour, the fact must be indicated as : "Sitka-Dyed Fox." Those in force in London provide that furs shall be described by, and sold under, their recognized trade names ; and that where one fur has been dyed to represent another the name of the original fur shall appear in the description. Thus, musquash dyed to represent seal is described as seal-musquash, opossum dyed to represent stone marten as stone marten opossum, etc. Where rabbit is the fur dyed it is described as coney, that being the trade name ; as, beaver coney, nutria coney, etc. The regulations as to description in fur trade centres outside the United Kingdom vary con siderably.

The Future.

The most serious problem confronting the fur trade of the world is that of raw material supplies, and its future will be powerfully influenced by the solution of, or the failure to solve, this problem. The world's consumption of raw furs has increased very considerably since the beginning of the loth century, and with the use of furs becoming more widespread every year this increase is bound to continue. The total number of wild fur-bearing animals, on the other hand, is probably decreas ing, this being due not only to the greater demand for their furs, but also to the gradual advance of civilization into regions hitherto open and unsettled. If these tendencies were allowed to operate unchecked a point would be within measurable distance at which grave anxiety as to the future supplies of furs would be justifiable; and in view of this possibility certain tentative precautions have already been taken. In Canada, the United States of America, Australia and elsewhere a policy of conservation of fur resources has been adopted, involving strict regulations as to preserves, close seasons, etc. ; and this, though not alone sufficient to solve the problem, is a wise and valuable step. Further aid in its solution is afforded by the ingenuity of the fur dressing and dyeing in dustry, which, as has already been pointed out, can provide sub stitutes for many rare skins by reproducing some of their charac teristics on skins more plentiful; and it is probable that scientific progress will enable this work to be extended considerably. The problem is also being attacked by the breeding of fur-bearing wild animals in captivity (see FUR FARMING). This has already given excellent results, and promises even more important ones. No doubt there are certain animals which it would be impossible to breed commercially in such conditions, but this method of secur ing future fur supplies is certainly a most valuable one. Combined with the conservation of existing fur-bearers, and aided by scien tific developments within the trade, it should go far towards pro viding an adequate and permanent supply of furs for the future.