The War in Italy

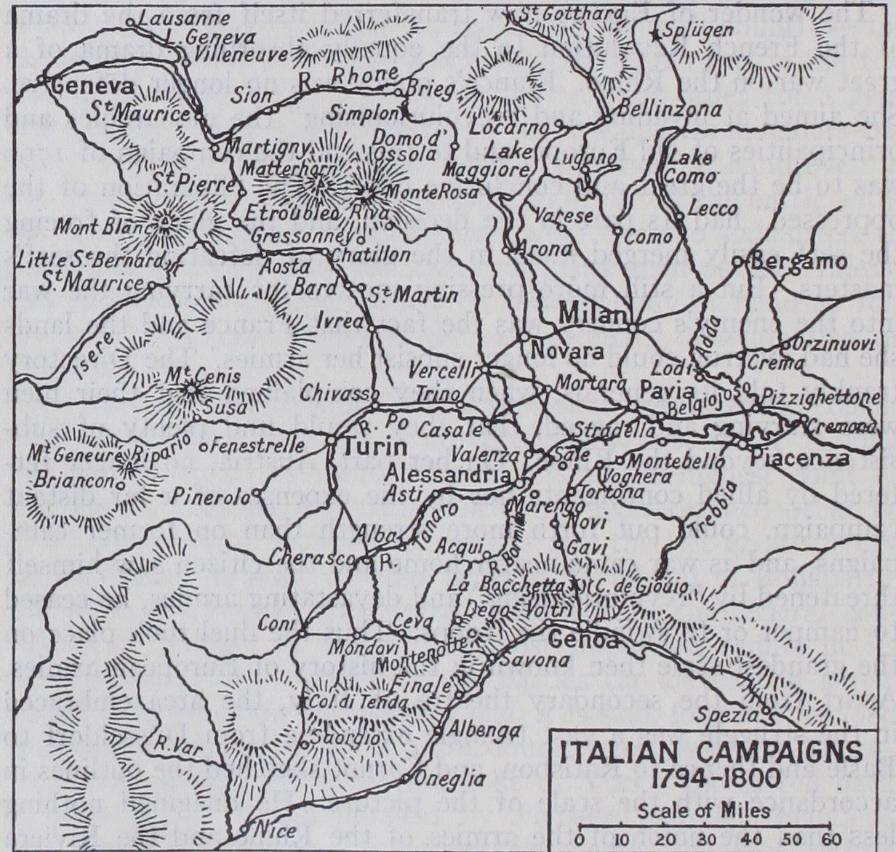

THE WAR IN ITALY Hitherto we have ignored the operations on the Italian fron tier, partly because they were of minor importance and partly because the conditions out of which Bonaparte's first campaign arose can be best considered in connection with that cam paign itself. It has been mentioned that in 1792 the French overran Savoy and Nice. In 1793 the Sardinian army and a small auxiliary corps of Austrians waged a desultory mountain warfare against the Army of the Alps about Briancon and the Army of Italy on the Var. That furious offensive on the part of the French, which signalized the year 1793 elsewhere, was made impossible here by the counter-revolution in the cities of the Midi. In when this had been crushed, the intention of the French govern ment was to take the offensive against the Austro-Sardinians. The first operation was to be the capture of Oneglia. The con centration of large forces in the lower Rhone valley had naturally infringed upon the areas told off for the provisioning of the Armies of the Alps (Kellermann) and of Italy (Dumerbion) ; indeed, the sullen population could hardly be induced to feed the troops suppressing the revolt, still less the distant frontier armies. Thus the only source of supply was the Riviera of Genoa : "Our connections with this district are imperilled by the corsairs of Oneglia (a Sardinian town) owing to the cessation of our opera tions afloat. The army is living from hand to mouth," wrote the younger Robespierre in Sept. 1793. Vessels bearing supplies from Genoa could not avoid the corsairs by taking the open sea, for there the British fleet was supreme. The Army of Italy began operations in April, and not only was Oneglia captured, but also the Col di Tenda. Napoleon Bonaparte served in these affairs on the headquarters staff. Meantime the Army of the Alps had possessed itself of the Little St. Bernard and Mont Cenis, and the Republicans were now (May) masters of several routes into Piedmont. But the Alpine roads merely led to fortresses, and both Carnot and Bonaparte—who had by now captivated the younger Robespierre and become the leading spirit in Dumerbion's army—considered that the Army of the Alps should be weakened to the profit of the Army of Italy, and that the time had come to disregard the feeble neutrality of Genoa, and to advance over the Col di Tenda.

Bonaparte in 1794.

Bonaparte's first suggestion for a rapid condensation of the French cordon, and an irresistible blow on the centre of the Allies by Tenda-Coni, came to nothing owing to the waste of time in negotiations between the generals and the distant Committee, and meanwhile new factors came into play. The capture of the pass of Argentera by the right wing of the Army of the Alps suggested that the main effort should be made against the barrier fortress of Demonte, but here again Bona parte proposed a concentration of effort on the primary and econ omy of force in the secondary objective. About the same time, in a memoir on the war in general, he laid down his most cele brated maxim : "The principles of war are the same as those of a siege. Fire must be concentrated on one point, and as soon as the breach is made, the equilibrium is broken and the rest is nothing." These tactical ideas of concentration and breaking the equilibrium he had already carried into the sphere of policy and strategy on the same lines. "Austria is the great enemy; Austria crushed, Ger many, Spain, Italy fall of themselves. We must not disperse, but concentrate our attack." Bonaparte argued that Austria could be effectively wounded by an offensive against Piedmont, and even more effectively by an ulterior advance from Italian soil into Ger many. But the younger Robespierre perished with his brother in the coup d'etat of 9th Thermidor, the advance was suspended, and Bonaparte, amongst other leading spirits of the Army of Italy, was arrested and imprisoned. Profiting by this moment, Austria increased her auxiliary corps, and the allied forces moved (in Sep tember) towards the Riviera. This threat to the French supplies was averted by the expedition of Dego, planned chiefly by Bona parte, who had been released from prison and was at headquarters, though unemployed.

Scherer and Kellermann.

In November 1794, Dumerbion was replaced by Scherer, who was soon transferred to the Spanish frontier, while the plan he left, as limited in scope as in force, was never put into execution, for spring had scarcely arrived when the prospect of renewed revolts in the south of France practically paralysed the army. This encouraged the enemy to deliver the blow that had so long been feared. Their combined forces, the Sardinians, the Austrian auxiliary corps and the newly arrived Austrian main army, advanced together and forced the French right wing to evacuate Vado and the Genoese littoral. But at this juncture the conclusion of peace with Spain released the Pyrenees armies, and Scherer returned to the Army of Italy at the head of reinforcements. He was faced with a difficult situation, but he had the means wherewith to meet it, as Bonaparte promptly pointed out. Up to this time, Bonaparte said, the French com manded the mountain crest, and therefore covered Savoy and Nice, and also Oneglia, Loano and Vado, the ports of the Riviera. But now that Vado was lost the breach was made. Genoa was cut off, and the south of France was the only remaining resource for the army commissariat. Vado must therefore be retaken and the line reopened to Genoa. But Bonaparte's mind ranged beyond the immediate future. He calculated that if the French advanced into the interior by the road Savona-Ceva, the Austrians would seek to cover Lombardy, the Piedmontese Turin, and this separation, already morally accomplished, it was to be the French general's task to accentuate in fact. Next, Sardinia having been coerced into peace, the Army of Italy would expel the Austrians from Lom bardy and connect its operations with those of the French in South Germany by way of Tirol. The supply question, once the soldiers had gained the rich valley of the Po, would solve itself.

Loano.

This was the essence of the first of four memoranda on this subject prepared by Bonaparte in his Paris office. The second indicated the means of coercing Sardinia—first the Austrians were to be driven or scared away towards Alessandria, then the French army would turn sharp to the left, driving the Sardinians eastward and north-eastward through Ceva, and this was to be the signal for the general invasion of Piedmont from all sides. In the third paper he framed an elaborate plan for the retaking of Vado, and in the fourth he summarized the contents of the other three. Having thus cleared his own mind as to the conditions and the solution of the problem, he did his best to secure the command for himself. The measures recommended by Bonaparte were translated into a formal and detailed order to recapture Vado. To Bonaparte the miserable condition of the Army of Italy was the most urgent incentive to prompt action. In Scherer's judg ment, however, the army was unfit to take the field, and there fore ex liypothesi to attack Vado, without thorough reorganization, and it was only in November that the advance was finally made. It culminated, thanks once more to the resolute Massena, in the victory of Loano (Nov. 23-24). But Scherer thought more of the destitution of his own army than of the fruits of success, and con tented himself with resuming possession of the Riviera. Mean while the mentor, whose suggestions and personality were equally repugnant to Scherer, had undegone strange vicissitudes of fortune —dismissal from the headquarters staff, expulsion from the list of general officers, and then the "whiff of grapeshot" of 13th Vendemiaire, followed shortly by his marriage with Josephine, and his nomination to command the Army of Italy. These events had neither shaken his cold resolution nor disturbed his balance.

Napoleon in Command.

The Army of Italy spent the win ter of 1795-96 as before in the narrow Riviera, while on the one side, just over the mountains, lay the Austro-Sardinians, and on the other, out of range of the coast batteries but ready to pounce on the supply ships, were the British frigates. On Bonaparte's left Kellermann, with no more than z 8,000, maintained a string of posts between Lake Geneva and the Argentera as before. Of the Army of Italy zo,000 watched the Tenda road and 12,000 the coast line. There remained for active operations some 2 7,00o men, ragged, famished and suffering in every way in spite of their vic tory of Loano. The Sardinian and Austrian auxiliaries (Colli), 25,000 men, lay between Mondovi and Ceva; a force strung out in the Alpine valleys opposed Kellermann ; and the main Austrian army (commanded by Beaulieu) in widely extended cantonments between Acqui and Milan, numbered 30,00o field troops. Thus the short-lived concentration of all the allied forces for the battle against Scherer had ended in a fresh separation. Austria was far more concerned with Poland than with the moribund French question, and committed as few of her troops as possible to this distant and secondary theatre of war. As for Piedmont, "peace" was almost the universal cry, even within the army. All this scarcely affected the regimental spirit and discipline of the Austrian squadrons and battalions, which had now recovered from the defeat of Loano. But they were important factors for the new general-in-chief on the Riviera, and formed the basis of his strategy.Bonaparte's first task was to grasp the reins and to prepare his troops, morally and physically, for active work. It was not merely that a young general with many enemies, a political fa vourite of the moment, had been thrust upon the army. The army itself was in a pitiable condition. Whole companies with their officers went plundering in search of mere food, the horses had never received as much as half-rations for a year past, and even the generals were half-starved. Thousands of men were barefooted and hundreds were without arms. But in a few days he had se cured an almost incredible ascendancy over the sullen, starved, half-clothed army.

"Soldiers," he told them, "you are famished and nearly naked. The government owes you much, but can do nothing for you. Your patience, your courage, do you honour, but give you no glory, no advantage. I will lead you into the most fertile plains of the world. There you will find great towns, rich provinces. There you will find honour, glory and riches. Soldiers of the Army of Italy, will you be wanting in courage?" He augmented his army of operations to about 40,00o, at the expense of the coast divisions, and set on foot also two small cav alry divisions, mounted on the half-starved horses that had sur vived the winter. Then he announced that the army was ready and opened the campaign. If the present separation of the Allies continued, he proposed to overwhelm the Sardinians first, before the Austrians could assemble from winter quarters, and then to turn on Beaulieu. If, on the other hand, the Austrians, before he could strike his blow, united with Colli, he proposed to frighten them into separating again by moving on Acqui and Alessandria. Hence Carcare, where the road from Acqui joined the "cannon road" over the Apennines to Ceva, was the first objective of his march, and from there he could manoeuvre and widen the breach between the allied armies. His scattered left wing would assist in the attack on the Sardinians as well as it could—for the imme diate attack on the Austrians its co-operation would of course have been out of the question. In any case he grudged every week spent in administrative preparation. The delay due to this, as a matter of fact, allowed a new situation to develop. Beaulieu was himself the first to move, and he moved towards Genoa in stead of towards his Allies. The gap between the two allied wings was thereby widened, but it was no longer possible for the French to use it, for their plan of destroying Colli while Beaulieu was in effective had collapsed.

In connection with a plan for a Genoese loan, and to facilitate the movement of supply convoys, a small French force had been pushed forward to Voltri. Bonaparte ordered it back as soon as he arrived at the front, but the alarm was given. The Austrians broke up from winter quarters at once, and rather than lose the food supplies at Voltri, Bonaparte actually reinforced Massena at that place, and gave him orders to hold on as long as possible, cautioning him only to watch his left rear (Montenotte). But he did not abandon his purpose. Starting from the new conditions, he devised other means, as we shall see, for reducing Beaulieu to in effectiveness. The French advance to Voltri had not only spurred Beaulieu into activity, but convinced him that the bulk of the French army lay east of Savona. He therefore made Voltri the object of a converging attack, not with the intention of destroying the French army but with that of "cutting its communications with Genoa and expelling it from the only place in the Riviera where there were sufficient ovens to bake its bread." As the Sardinians and auxiliary Austrians were ordered to extend leftwards on Dego to close the gap that Beaulieu's advance on Genoa-Voltri opened up, and the furthest to the right of Beaulieu's own columns had orders to seize Monte Legino, the wings were therefore so far connected that Colli wrote to Beaulieu on this day "the enemy will never dare to place himself between our two armies." The event belied the prediction, and the proposed minor operation against granaries and bakeries became the first act of a decisive campaign.

On the night of April 9 the French were grouped as follows: brigades under Garnier and Macquard at the Finestre and Tenda passes, Serurier's division and Rusca's brigade east of Garessio; Augereau's division about Loano, Meynier's at Finale, Laharpe's at Savona with an outpost on the Monte Legino, and Cervoni's brigade at Voltri. Massena was in general charge of the last named units. The cavalry was far in rear beyond Loano. Colli's main force was around Coni and Mondovi-Ceva, the latter group connecting with Beaulieu by a detachment under Provera between Millesimo and Carcare. Of Beaulieu's army, Argenteau's division, still concentrating to the front in many small bodies, extended over the area Acqui-Dego-Sassello. Vukassovich's brigade was equally extended between Ovada and the mountain-crests above Voltri, and Pittoni's division was grouped around. Gavi and the Bocchetta, the two last units being destined for the attack on Voltri. Farther to the rear was Sebottendorf's division around Alessandria-Tortona. On the afternoon of the loth Beaulieu de livered his blow at Voltri, not, as he anticipated, against three quarters of the French army, but against Cervoni's detachment. This, after a long irregular fight, slipped away in the night to Savona. Discovering his mistake next morning, Beaulieu sent back some of his battalions to join Argenteau. But there was no road by which they could do so save the detour through Acoui and Dego, and long before they arrived Argenteau's advance on Monte Legino had forced on the crisis. On the i ith (a day be hind time), this general drove in the French outposts, but he soon came on three battalions under Col. Rampon, who threw himself into some old earthworks that lay near, and said to his men, We must win or die here, my friends." His redoubt and his men stood the trial well, and when day broke on the 12th Bonaparte was ready to deliver his first "Napoleon-stroke." Montenotte.—The principle that guided him in the subsequent operations may be called that of "concentrating a temporary superiority of force at the point of balance." Touch had been gained with the enemy all along the long line between the Tenda and Voltri, and he decided to concentrate swiftly upon the nearest enemy—Argenteau. Augereau's division, or such part of it as could march at once, was ordered to Mallare. Massena, with 9,000 men, was to send two brigades in the direction of Carcare and Altare, and with the third to swing round Argenteau's right and to head for Montenotte village in his rear. Laharpe with 7,000 (it had become clear that the enemy at Voltri would not pursue their advantage) was to join Rampon, leaving only Cervoni and two battalions in Savona. Serurier and Rusca were to keep the Sar dinians in front of them occupied. The far-distant brigades of Garnier and Macquard stood fast, but the cavalry drew eastward as quickly as its condition permitted. In rain and mist on the early morning of the 12th the French marched up from all quar ters, while Argenteau's men waited in their cold bivouacs for light enough to resume their attack on Monte Legino. About nine the mists cleared, and heavy fighting began, but Laharpe held the mountain, and Massena with his nearest brigade stormed forward against Argenteau's right. A few hours later, seeing Augereau's columns heading for their line of retreat, the Austrians retired, sharply pressed, on Dego. The threatened intervention of Provera was checked by Augereau's presence at Carcare.

Montenotte was a brilliant little victory, and one can imagine its effects on the but lately despondent soldiers of the Army of Italy, but only two-thirds of Argenteau's force, and none of the other divisions, had been beaten, and the heaviest fighting was to come. Bonaparte, eager to begin at once the subjugation of the Piedmontese (for which purpose he wanted to bring Serurier and Rusca into play) sent only Laharpe's division and a few details of Massena's, under the latter, towards Dego. These were to pro tect the main attack from interference by the forces that had been engaged at Montenotte (imagined to be Beaulieu's main body), the said main attack being delivered by Augereau's division, reinforced by most of Massena's, on the positions held by Provera. The latter, only i,000 strong to Augereau's 9,000, shut himself in the castle of Cossaria, which, imitating Rampon, he defended against a series of furious assaults. Not until the morning of the 14th was his surrender secured, after his ammunition and food had been exhausted.

Argenteau also won a day's respite on the 13th, for Laharpe did not join Massena till late, and nothing took place opposite Dego but a little skirmishing. During the day Bonaparte saw for him self that he had overrated the effects of Montenotte. Beaulieu, on the other hand, underrated them, treating it as a mishap that was more than counterbalanced by his own success in "cutting off the French from Genoa." He began to reconstruct his line on the front Dego-Sassello, trusting to Colli to harry the French until the Voltri troops had finished their detour through Acqui and re joined Argenteau. This, of course, presumed that Argenteau's troops were intact and Colli's able to move, which was not the case with either. Not until the afternoon of the 14th did Beaulieu place a few extra battalions at Argenteau's disposal "to be used only in case of extreme necessity," and order Vukassovich from the region of Sassello to "make a diversion" against the French right with two battalions.

Dego.

Thus Argenteau, already shaken, was exposed to de struction. On the 14th, after Provera's surrender, Massena and Laharpe, reinforced until they had nearly a two-to-one supe riority, stormed Dego and killed or captured 3,000 of Argenteau's 5,500 men, the remnant retreating in disorder to Acqui. But noth ing was done towards the accomplishment of the purpose of destroying Colli on that day, save that Serurier and Rusca began to close in to meet the main body between Ceva and Millesimo. Moreover, the victory at Dego had produced its usual results on the wild fighting swarms of the Republicans, who threw them selves like hungry wolves on the little town, without pursuing the beaten enemy or even placing a single outpost on the Acqui road. In this state, during the early hours of the r 5th, Vukassovich's brigade,' marching up from Sassello, surprised them, and they broke and fled in an instant. The whole morning had to be spent in rallying them at Cairo, and Bonaparte had for the second time to postpone his union with Serurier and Rusca, who meanwhile, isolated from one another and from the main army, were groping forward in the mountains. A fresh assault on Dego was ordered, and after very severe fighting, Massena and Laharpe succeeded late in the evening in retaking it. Vukassovich lost heavily, but retired steadily and in order on Spigno. The killed and wounded numbered probably about i,000 French and 1,5oo Austrians, out of considerably less than io,000 engaged on each side—a loss which contrasted very forcibly with those suffered in other bat tles of the Revolutionary Wars, and by teaching the Army of Italy to bear punishment, imbued it with self-confidence. But again success bred disorder, and there was a second orgy in the houses and streets of Dego which went on till late in the morning and paralysed the whole army.

This was perhaps the crisis of the campaign. Even now it was not certain that the Austrians had been definitively pushed aside, while it was quite clear that Beaulieu's main body was intact and Colli was still more an unknown quantity. But Bonaparte's inten tion remained the same, to attack the Piedmontese as quickly and as heavily as possible, Beaulieu being held in check by a containing force under Massena and Laharpe. The remainder of the army, counting in now Rusca and Serurier, was to move westward to wards Ceva. This disposition, while it illustrates the Napoleonic principle of delivering a heavy blow on the selected target and warding off interference at other points, shows also the difficulty of rightly apportioning the available means between the offensive mass and the defensive system, for, as it turned out, Beaulieu was already sufficiently scared, and thought of nothing but self defence on the line Acqui-Ovada-Bocchetta, while the French of fensive mass was very weak compared with Colli's unbeaten and now fairly concentrated army about Ceva.

On the afternoon of the i6th the real avalanche was begun by Augereau's division, reinforced by other troops. Rusca joined 'Vukassovich had received Beaulieu's order to demonstrate with two battalions, and also appeals for help from Argenteau. He therefore brought most of his troops with him.

Augereau towards evening, and Serurier approached Ceva from the south. Colli's object was now to spin out time, and having re pulsed a weak attack by Augereau, and feeling able to repeat these tactics on each successive spur of the Apennines, he retired in the night to a new position behind the Cursaglia. On the i 7th, reas sured by the absence of fighting on the Dego side, and by the news that no enemy remained at Sassello, Bonaparte released Massena from Dego, leaving only Laharpe there, and brought him over towards the right of the main body, which thus on the evening of the i 7th formed a long straggling line on both sides of Ceva, Serurier on the left, echeloned forward, Augereau, Joubert and Rusca in the centre, and Massena, partly as support, partly as flank guard, on Augereau's right rear. Serurier had been bidden to extend well out and to strive to get contact with Massena, i.e., to encircle the enemy. The line of supply, as an extra guarantee against interference, was changed from that of Savona-Carcare to that of Loano-Bardinetto. When this was accomplished, four clear days could be reckoned with certainty in which to deal with Colli.

The latter, still expecting the Austrians to advance to his as sistance, had established his corps (not more than 12,000 mus kets in all) in the immensely strong positions of the Cursaglia. Opposite this position the French arrived, after many delays due to the weariness of the troops, on the i9th. A day of irregular fighting followed, everywhere to the advantage of the defenders. Bonaparte, fighting against time, ordered a fresh attack on the 20th, and only desisted when it became evident that the army was exhausted, and, in particular, when Serurier reported frankly that without bread the soldiers would not march. The delay thus imposed, however, enabled him to clear the "cannon-road" of all vehicles, and to bring up the Dego detachment to replace Massena in the valley of the western Bormida, the latter coming in to the main army. Twenty-four thousand men, for the first time with a due proportion of cavalry and artillery, were now disposed along Colli's front and beyond his right flank. Colli, outnumbered by two to one, and threatened with envelopment, decided once more to retreat, and the Republicans occupied the Cursaglia lines on the morning of the 21st without firing a shot. But Colli halted again at Vico, half-way to Mondovi, and while he was in this unfavourable situation the pursuers came on with true Repub lican swiftness, lapped round his flanks and crushed him. A few days later (April 27), the armistice of Cherasco put an end to the campaign before the Austrians moved a single battalion to his assistance.

The Napoleon Touch.

The interest of the campaign lies in the "Napoleon touch" that differentiated it from other Revolu tionary campaigns. Revolutionary energy was common to the Army of Italy and to the Army of the North. Why, therefore, when the war dragged on from one campaign to another in the great plains of the Meuse and Rhine countries, did Bonaparte bring about so swift a decision in these cramped valleys? The answer is to be found partly in the exigencies of the supply service, but still more in Bonaparte's own personality and the strategy born of it. Action of some sort was the plain alternative to starva tion. He would have no quarter-rations on the Riviera, but plenty and to spare beyond the mountains. Strategical conditions and "new French" methods of war did not save Bonaparte in the two crises—the Dego rout and the sullen halt of the army at San Michele—but the personality which made the soldiers, on the way Montenotte, march barefoot past a wagon-load of new boots. Later critics evolved from his success the theory of "interior lines," but actually the method was in many respects old. What, therefore, in the theory or its application was the product of Bonaparte's own genius and will? A comparison with Souham's campaign of Tourcoing will enable us to answer this question. To begin with, Souham found himself midway between Coburg and Clerfayt almost by accident, and his utilization of the advan tages of his position was an expedient for the given case. Bona parte, however, placed himself deliberately in an analogous situ ation at Carcare and Cairo. Then he swifty "concentrated fire, made the breach, and broke the equilibrium" at the spot where the interests and forces of the two allies converged and diverged.

Relative Superiority. Another

guiding idea was that of "relative superiority." Whereas Souham had been in superior force (90,00o against 70,o00), Bonaparte (40,000 against so,000) was not, and yet the Army of Italy was always placed in a posi tion of relative superiority (at first about 3 to 2 and ultimately 2 to i) to the immediate antagonist. "The essence of strategy," said Bonaparte in 1797, "is, with a weaker army, always to have more force at the crucial point than the enemy. But this art is taught neither by books nor by practice ; it is a matter of tact." In this he expressed the result of his victories on his own mind rather than a preconceived formula which produced those vic tories. But the idea, though undefined, and the method of prac tice, though imperfectly worked out, were in his mind from the first. As soon as he had made the breach, though preparing to throw all available forces against Colli, he posted Massena and Laharpe at Dego to guard, not like Vandamme on the Lys against a real and pressing enemy, but against a possibility, and he only diminished the strength and altered the position of this pro tective detachment in proportion as the Austrian danger dwindled. Later in his career he defined this system as "having all possible strength at the decisive point," and "being nowhere vulnerable," and the art of reconciling these two requirements, in each case as it arose, was always the principal secret of his generalship. At first his precautions (judged by events and not by the probabili ties of the moment) were excessive, and the offensive mass small. But the point is that such a system, however rough its first model, had been imagined and put into practice.The first phase of the campaign satisfactorily settled, Bonaparte was free to turn his attention to the "arch-enemy" to whom he was now considerably superior in numbers (35,00o to 25,00o). The day after the signature of the armistice of Cherasco he began preparing for a new advance and also for the role of arbiter of the destinies of Italy. Beaulieu had fallen back into Lombardy, and now bordered the Po right and left of Valenza. To achieve further progress, Bonaparte had first to cross that river, and the point and method of crossing was the immediate problem, a prob lem the more difficult as he had no bridge train and could only make use of such existing bridges as he could seize intact. If he crossed above Valenza he would be confronted by one river-line after another. Milan was his objective, and Tortona-Piacenza his indirect route thither. To give himself every chance he had stipulated with the Piedmontese authorities for the right of pass ing at Valenza, and he had the satisfaction of seeing Beaulieu fall into the trap and concentrate opposite that part of the river. The French meantime had moved to the region Alessandria-Tor tona. Thence on May 6 Bonaparte set out for a forced march on Piacenza, and that night the advanced guard was 3om. on the way, at Castel San Giovanni, and Laharpe's and the cavalry divisions at Stradella, iom. behind them. Augereau was at Broni, Massena at Salo and Serurier near Valenza, the whole forming a rapidly extending fan, 5om. from point to point. If the Piacenza detach ment succeeded in crossing, the army was to follow rapidly in its track. If, on the other hand, Beaulieu fell back to oppose the advanced guard, the Valenza divisions would take advantage of his absence to cross there. In either case, be it observed, the Austrians were to be evaded, not brought to action. On the 7th, the advanced guard under Dallemagne crossed at Piacenza,' and, hearing of this, Bonaparte ordered every division except Serurier's thither with all possible speed. In the exultation of the moment he mocked at Beaulieu's incapacity, but the old Austrian wail already on the alert. This game of manoeuvres he understood; already one of his divisions had arrived in close proximity to Dallemagne and the others were marching eastward by all avail able roads. But the mobility of the French enabled them to pass the river bef ore the Austrians (who had actually started a day in advance of them) put in an appearance, and afterwards to be in superior numbers at each point of contact. The culmina tion Bonaparte himself indicated as the turning-point of his life.

'On entering the territory of the duke of Parma, Bonaparte imposed, besides other contributions, the surrender of 20 famous pictures, and thus began a practice which for many years enriched the Louvre and only ceased with the capture of Paris in 1814.

"Vendemiaire and even Montenotte did not make me think myself a superior being. It was after Lodi that the idea came to me • • • that first kindled the spark of boundless ambition." Lodi.--Abandoning his original idea of giving battle, Beaulieu retired to the Adda, and most of his troops were safely beyond it before the French arrived near Lodi, but he felt it necessary to leave a strong rearguard on the river opposite that place to cover the reassembly of his columns after their scattered march. On the afternoon of May 1o, Bonaparte, with Dallemagne, Massena and Augereau, came up and seized the town. But 2ooyds. of open ground had to be passed from the town gate to the bridge, and the bridge itself was another 25oyds. in length. A few hundred yards beyond it stood the Austrians, 9,00o strong with 14 guns. Bonaparte brought up all his guns to prevent the enemy from destroying the bridge. Then sending all his cavalry to turn the enemy's right by a ford above the town, he waited two hours, employing the time in cannonading the Austrian lines, resting his advanced infantry and closing up Massena's and Augereau's divisions. Finally he gave the order to Dallemagne's 4,000 grenadiers, who were drawn up under cover of the town wall, to rush the bridge. As the column, not more than 3o men broad, made its appearance, it was met by the concentrated fire of the Austrian guns, and half way across the bridge it checked, but Bonaparte himself and Massena rushed forward, the courage of the soldiers revived, and, while some jumped off the bridge and scrambled forward in the shallow water, the remainder stormed on, passed through the guns and drove back the infantry. This was, in bare outline, the astounding passage of the bridge of Lodi. It was not till after the battle that Bonaparte realized that only a rearguard was in front of him. When he launched his 4,000 grenadiers he thought that on the other side there were four or five times that number of the enemy. No wonder, then, that after the event he recognized in himself the flash of genius, the courage to risk everything, and the "tact" which, independent of and indeed contrary to all reasoned calculations, told him that the moment had come for "breaking the equi librium." Lodi was a tactical success in the highest sense, in that the principles of his tactics rested on psychology—on the "sublime" part of the art of war as Saxe had called it long ago. The spirit produced the form, and Lodi was the prototype of the Napoleonic battle—contact, manoeuvre, preparation and finally the well-timed, massed and unhesitating assault. The failure to reap the strategical fruits mattered little. Many months elapsed before this bold assertion of superiority ceased to decide the battles of France and Austria.

Milan.—Next day he set off in pursuit of Beaulieu, postpon ing his occupation of the Milanese, but the Austrians were now out of reach, and during the next few days the French divisions were installed at various points in the area Pavia-Milan-Pizzighe tone, facing outwards in all dangerous directions, with a central reserve at Milan. Thus secured, Bonaparte turned his attention to political and military administration. This took the form of exacting from the neighbouring princes money, supplies and ob jects of art, and the once famished Army of Italy revelled in its opportunity. Now, however, the Directory, suspicious of the too successful and too sanguine young general, ordered him to turn over the command in Upper Italy to Kellermann, and to take an expeditionary corps himself into the heart of the peninsula, there to preach the Republic and the overthrow of princes. Bona parte absolutely refused, and offered his resignation. In the end (partly by bribery) he prevailed, but the incident reawakened his desire to close with Beaulieu. This indeed he could now do with a free hand, since not only had the Milanese been effectively occupied, but also the treaty with Sardinia had been ratified. But no sooner had he resumed the advance than it was inter rupted by a rising of the peasantry in his rear. The exactions of the French had in a few days generated sparks of discontent which it was easy for the priests and the nobles to fan into open flames. Milan and Pavia as well as the countryside broke into insurrection, and at the latter place the mob forced the French commandant to surrender. Bonaparte acted swiftly and ruth lessly. Bringing back a small portion of the army with him. he punished Milan on the 25th, sacked and burned Binasco on the 26th, and on the evening of the latter day, while his cavalry swept the open country, he broke his way into Pavia with 1,500 men and beat down all resistance. Then he advanced to the banks of the Mincio, where the remainder of the Italian campaign was fought out, both sides contemptuously disregarding Venetian neutrality. It centred on the fortress of Mantua, which Beaulieu, too weak to keep the field, and dislodged from the Mincio in the action of Borghetto (May 30), strongly garrisoned before retir ing into Tirol. Beaulieu was soon afterwards replaced by Wurm ser who brought reinforcements from Germany.

At this point, mindful of the narrow escape he had had of losing his command, Bonaparte thought it well to begin the resettlement of Italy. The scheme for co-operating with Moreau on the Danube was indefinitely postponed, and the Army of Italy (now reinforced from the Army of the Alps) was again disposed in a protective "zone of manoeuvre," with a strong central reserve. Against Mantua no siege artillery was available till the Austrians in the citadel of Milan capitulated, and thus not till July 18 was the first parallel begun. Almost at the same moment Wurmser began his advance from Trent with 55,00o men to relieve Mantua.

Siege of Mantua.—The protective system on which his attack would fall in the first instance was now as follows : Augereau (6,000) about Legnago, Despinoy (8,000) south-east of Verona, Massena (13,000) at Verona and Peschiera, Sauret (4,500) at Salo and Gavardo. Serurier (12,000) was besieging Mantua, and the only central reserve was the cavalry (2,00o) under Kilmaine. The main road to Milan passed by Brescia. Sauret's brigade, therefore, was practically a detached post on the line of com munication, and on the main defensive front less than 30,000 men were disposed at various points between La Corona and Legnago (30m. apart), and at a distance of 15 to tom. from Mantua. The strength of such a disposition depended on the fighting power and handiness of the troops, who in each case would be called upon to act as a rearguard to gain time. The lie of the country scarcely permitted a closer grouping, unless Bonaparte fell back on the old-time device of a "circumvalla tion," and shut himself up in a ring of earthworks round Mantua —and this was impossible for want of supplies.

As Wurmser's attack procedure has received almost universal condemnation, in justice it may be pointed out that the object of the expedition was not to win a battle by falling on the dis united French with a well-concentrated army, but to overpower one, any one, of the corps covering the siege, and to press straight forward to the relief of Mantua. New ideas and new forces, undiscernible to a man of 72 years of age, obliterated his achieve ment by surpassing it ; but such as it was--a limited use of force for a limited object—the venture undeniably succeeded.

The Austrians formed three corps, one (Quasdanovich, 18,000 men) marching round the west side of the lake of Garda, the second (under Wurmser, about 30,000) moving directly down the Adige, and the third (Davidovich, 6,000) making a detour by the Brenta valley and heading for Verona by Vicenza. On the 29th Quasdanovich attacked Sauret at Salo, drove him towards Desenzano, and pushed on to Gavardo and thence into Brescia. Wurmser expelled Massena's advanced guard from La Corona, and captured in succession the Monte Baldo and Rivoli posts. The Brenta column approached Verona with little or no fighting. News of this column led Bonaparte early in the day to close up Des pinoy, Massena and Kilmaine at Castelnuovo, and to order Auge reau from Legnago to advance on Montebello (19m. east of Verona) against Davidovich's left rear. But after these orders had been despatched came the news of Sauret's defeat, and this moment was one of the most anxious in Bonaparte's career. He could not make up his mind to give up the siege of Mantua, but he hurried Augereau back to the Mincio, and sent order after order to the officers on the lines of communication to send all convoys by the Cremona instead of by the Brescia road. More, he wrote to Serurier a despatch which included the words "per haps we shall recover ourselves . . . but I must take serious measures for a retreat." On the 30th he wrote : "The enemy have broken through our line in three places . . . and • . . cap tured Brescia. You see that our communications with Milan and Verona are cut." Early reports that day enabled him to "place" the main body of the enemy opposite Massena, and this at least helped to make his course less doubtful. Augereau was ordered to hold the line of the Molinella, in case Davidovich's attack, the least-known factor, should after all prove to be serious ; Massena to hold Wurmser at Castelnuovo as long as he could. Sauret and Despinoy were concentrated at Desenzano with orders on the 31st to clear the main line of retreat and to recapture Brescia. On the Austrian side Quasdanovich wheeled inwards, his right finally resting on Montechiaro and his left on Salo, and Wurmser drove back Massena to the west side of the Mincio. Davidovich made a slight advance.

In the late evening Bonaparte held a council of war at Rover bella. The proceedings of this council are unknown, but it at any rate enabled Bonaparte to see clearly and to act. Hitherto he had been covering the siege of Mantua with various detach ments, the defeat of any one of which might be fatal to the enter prise. Thus, when he had lost his main line of retreat, he could assemble no more than 8,000 men at Desenzano to it back. Now, however, he made up his mind that the siege could not be continued, and bitter as was the decision, it gave him freedom. At this moment of crisis the instincts of the great captain came into play, and showed the way to a victory that would more than counterbalance the now inevitable failure. Serurier was ordered to spike the 140 siege guns which had been so welcome a few days before, and, after sending part of his force to Augereau, to estab lish himself with the rest at Marcaria on the Cremona road. The field forces were to be used on interior lines. On the 31st Sauret, Despinoy, Augereau and Kilmaine advanced westward against Quasdanovich. The first two found the Austrians at Salo and Lonato and drove them back, while with Augereau and the cavalry Bonaparte himself made a forced march on Brescia, never halting night or day till he reached the town and recovered his depots. Meantime Massena had gradually drawn in towards Lonato, Serurier had retired (night of July 31) from before Mantua, and Wurmser's advanced guard triumphantly entered the fortress (Aug. 1).

Lonato and Castiglione.

The Austrian general now formed the plan of crushing Bonaparte between Quasdanovich and his own main body. But meantime Quasdanovich had evacuated Brescia under the threat of Bonaparte's advance and was now fighting a long irregular action with Despinoy and Sauret about Gavardo and Salo, and Bonaparte, having missed his expected target, had brought Augereau by another severe march back to Montechiaro. Massena was now assembled between Lonato and Ponte San Marco. Wurmser's main body, weakened by the detachment sent to Mantua, crossed the Mincio about Valeggio and Goito on the 2nd, and penetrated as far as Castiglione, whence Massena's rearguard was expelled. But a renewed advance of Quasdanovich, ordered by Wurmser, which drove Sauret and Despinoy back on Brescia and Lonato, in the end only placed a strong detachment of the Austrians within striking distance of Massena, who on the 3rd attacked and destroyed it, while at the same time Augereau recaptured Castiglione from Wurmser. On the 4th Sauret and Despinoy pressed back Quasdanovich beyond Salo and Gavardo, and Massena annihilated an isolated column which tried to break its way through to Wurmser. Wurmser, thinking rightly or wrongly that he could not now retire to the Mincio without a battle, drew up his whole force, close on 30,000 men, in the plain between Solferino and Medole. The finale may be described in very few words. Bonaparte, convinced that no more was to be feared from Quasdanovich, called in Despinoy's division to the main body and sent orders to Serurier, then far distant on the Cremona road, to march against the left flank of the Austrians. On the 5th the battle of Castiglione (q.v.) was fought. Closely contested in the first hours of the frontal attack till Serurier's arrival decided the day, it ended in the retreat of the Austrians over the Mincio and into Tirol, whence they had come.Thus the new way had failed to keep back Wurmser, and the old had failed to crush Bonaparte. In former wars a commander threatened as Bonaparte was would have fallen back at once to the Adda, abandoning the siege in such good time that he would have been able to bring off his siege artillery. Instead of this Bonaparte hesitated long enough to lose it, which, according to accepted canons, was a waste, and held his ground, which was, by the same rules, sheer madness. But revolutionary discipline was not firm enough to stand a retreat. Once it turned back, the army would have streamed away to Milan and perhaps to the Alps (cf. 1799). As to the manner of this fighting, even the prin ciple of "relative superiority" failed him so long as he was endeav ouring to cover the siege and again when his chief care was to protect his new line of retreat and to clear his old. In this period, viz., up to his return from Brescia on Aug. 2, the only "mass" he collected delivered a blow in the air, while the covering detach ments had to fight hard for bare existence. Once released from its trammels, the Napoleonic principle had fair play. He stood between Wurmser and Quasdanovich, ready to fight either or both. The latter was crushed, thanks to local superiority and the resolute leading of Massena, but at Castiglione Wurmser actually outnumbered his opponent till the last of Bonaparte's precaution ary dispositions had been given up, and Serurier brought back from the "alternative line of retreat" to the battlefield. The moral is, again, that it was not the mere fact of being on interior lines that gave Bonaparte the victory, but his "tact," his fine apprecia tion of the chances in his favour, measured in terms of time, space, attacking force and containing power. All these factors were greatly influenced by the ground, which favoured the swarms and columns of the French and deprived the brilliant Austrian cav alry of its power to act. But of far greater importance was the mobility that Bonaparte's personal force imparted to the French. Bonaparte himself rode five horses to death in three days, and Augereau's division marched from Roverbella to Brescia and back to Montechiaro, a total distance of nearly som., in about 36 hours. This indeed was the foundation of his "relative superi ority," for every hour saved in the time of marching meant more freedom to destroy one corps before the rest could overwhelm the covering detachments and come to its assistance.

By the end of the second week in August the blockade of Mantua had been resumed, without siege guns. But still under the impression of a great victory gained, Bonaparte was planning a long forward stride. He thought that by advancing past Mantua directly on Trieste and thence onwards to the Semmering he could impose a peace on the emperor. The Directory, however, which had by now focussed its attention on the German campaign, or dered him to pass through Tirol and to co-operate with Moreau, and this plan, Bonaparte, though protesting against an Alpine venture being made so late in the year, prepared to execute. Wurmser was thought to have posted his main body near Trent, and to have detached one division to Bassano "to cover Trieste." The French advanced northward on the 2nd, in three disconnected columns which successfully combined and drove the enemy before them to Trent. There, however, they missed their target. Wurm ser had already drawn over the bulk of his army (22,000) into the Val Sugana, whence with the Bassano division as his advanced guard, he intended once more to relieve Mantua, while David ovich with 13,000 (excluding detachments) was to hold Tirol against any attempt of Bonaparte to join forces with Moreau. Thus Austria was preparing to hazard a second (as in the event she hazarded a third and a fourth) highly trained and expen sive professional army in the struggle for the preservation of a fortress, and we must conclude that there were weighty reasons which actuated so notoriously cautious a body as the Council of War in making this unconditional venture. While Mantua stood, Bonaparte, for all his energy and sanguineness, could not press forward into Friuli and Carniola, and immunity from a Republican visitation was above all else important for the Vienna statesmen, governing as they did more or less discontented and heterogeneous populations that had not felt the pressure of war for a century and more. If we neglect pure theory, and regard strategy as the handmaiden of statesmanship—which fundamen tally it is—we cannot condemn the Vienna authorities unless it be first proved that they grossly exaggerated the possible results of Bonaparte's threatened irruption.

Bassano.

When Massena entered Trent on the morning of Sept. 5, Bonaparte became aware that the force in his front was a mere detachment, and news soon came in that Wurmser was in the Val Sugana about Primolano and at Bassano. This move he supposed to be intended to cover Trieste. He therefore in formed the Directory that he could not proceed with the Tirol scheme, and spent one more day in driving Davidovich well away from Trent. Then leaving Vaubois to watch him, Bonaparte marched Augereau and Massena, with a rapidity he scarcely ever surpassed, into the Val Sugana. Wurmser's rearguard was at tacked and defeated again and again, and Wurmser himself felt compelled to stand and fight, in the hope of checking the pursuit before reaching the plains. Half his army had already reached Montebello on the Verona road, and with the rear half he posted himself at Bassano, where on the 8th he was defeated with heavy losses. Then began a strategic pursuit or general chase, and in this Bonaparte at first directed the pursuers so as to cut off Wurmser from Trieste, not fron Mantua. Late on the 9th, Bona parte realized that his opponent was heading for Mantua via Legnago and despite the fresh cast his net closed so rapidly that Wurmser barely succeeded in reaching Mantua on the 12th, with all the columns of the French, weary as most of them were, con verging in hot pursuit. After an attempt to keep the open field, defeated in a general action on the 15th, the relieving force was merged in the garrison, now some 28,000 in all. So ended the episode of Bassano, the most brilliant feature of which was the marching power of the French infantry. Between the 5th and the 11th, besides fighting three actions, Massena had marched loom. and Augereau 114.Alvintzi was now appointed to command a new army of relief. Practically the whole of the fresh forces available were in Carni ola, the military frontier, etc., while Davidovich was still in Tirol. Alvintzi's intention was to assemble his new army (29,000) in Friuli, and to move on Bassano. Meantime, Davidovich (i8,000) was to capture Trent, and the two columns were to connect by the Val Sugana. All being well, Alvintzi and Davidovich, still separate, were then to converge on the Adige between Verona and Legnago. Wurmser was to co-operate by vigorous sorties. At this time Bonaparte's protective system was as follows : Kilmaine (9,000) investing Mantua, Vaubois (Io,000) at Trent, and Massena (9,000) at Bassano and Treviso, Augereau (9,000) and Macquard (3,000) at Verona and Villafranca constituting, for the first time in these operations, important mobile reserves. Hearing of Alvintzi's approach in good time, he meant first to drive back Davidovich, then with Augereau, Massena, Macquard and 3,000 of Vaubois's force to fall upon Alvintzi who, he calculated, would at this stage have reached Bassano, and finally to send back a large force through the Val Sugana to attack Davidovich. This plan miscarried.

By Nov. 7 Davidovich had forced Vaubois back to Rivoli, and Alvintzi pressed forward within 5m. of Vicenza. Bonaparte watched carefully for an opportunity to strike out, and on the 8th massed his troops closely around the central part of Verona. On the 9th, to give himself air, he ordered Massena to join Vaubois, and to drive back Davidovich at all costs. But before this order was executed, reports came in that Davidovich had suspended his advance. The loth and i i th were spent by both sides in relative inaction, the French waiting on events and opportunities, the Austrians resting after their prolonged exertions. Then on the afternoon of the 11th, being informed that Alvintzi was approach ing, Bonaparte decided to attack him. On the 12th Alvintzi's ad vanced guard was assailed at Caldiero. But the troops in rear came up rapidly, and by 4 P.M. the French were defeated all along the line and in retreat on Verona. Bonaparte's situation was now indeed precarious. He was on "interior lines" it is true, but he had neither the force nor the space necessary for the delivery of rapid radial blows. Alvintzi was in superior numbers, as Caldiero had proved, and at any moment Davidovich, who had twice Vaubois' force, might advance to the attack of Rivoli. The reserves had proved insufficient, and Kilmaine had to be called up from Man tua, which was thus for the third time freed from the blockaders. Bonaparte chose a daring move on the enemy's rear in preference to the hazards of a retreat, though it was not until the evening of the 14th that he actually issued the fateful order.

The Austrians, too, had selected the 1 Sth as the date of their final advance on Verona, Davidovich from the north, Alvintzi via Zevio from the south. But Bonaparte was no longer there ; leaving Vaubois to hold Davidovich as best he might, he had collected the rest of his small army between Albaro and Ronco. His plan seems to have been to cross the Adige well in rear of the Austrians, to march north and establish himself on the Verona-Vicenza highway, where he could supply himself from their convoys. The troops passed the Adige in three columns near Ronco and Albaredo, and marched forward along the dikes, with deep marshes and pools on either hand. If Bonaparte's intention was to reach the dry open ground of San Bonifacio in rear of the Austrians, it was not realized, for the Austrian army, instead of being at the gates of Verona, was still between Caldiero and San Bonifacio, heading, as we know, for Zevio. Thus Alvintzi was able, easily and swiftly, to wheel to the south.

Arcola.

The battle of Arcola almost defies description. The first day passed in a series of resultless encounters between the heads of the columns as they met on the dikes. In the evening Bonaparte withdrew over the Adige, expecting every moment to be summoned to Vaubois' aid. But Davidovich remained inactive, and on the 16th the French again crossed the river. Massena from Ronco advanced on Porcile, driving the Austrians along the cause way thither, but on the side of Arcola, Alvintzi had deployed a considerable part of his forces on the edge of the marshes, within musket shot of the causeway by which Bonaparte and Augereau had to pass, along the Austrian front, to reach the bridge of Arcola. In these circumstances the second day's battle was more murder ous and no more decisive than the first, and again the French re treated to Ronco. But Davidovich again stood still, and with ex traordinary resolution, Bonaparte ordered a third assault for the I 7th, trying a fresh tactical move. Massena again advanced on Porcile, Robert's brigade on Arcola, but the rest, under Augereau, were to pass the Alpone near its confluence with the Adige, and joining various small bodies which passed the main stream lower down, to storm forward on dry ground to Arcola. The Austrians, however, themselves advanced from Arcola, overwhelmed Robert's brigade on the causeway and almost reached Ronco. This was perhaps the crisis of the battle, for Augereau's force was now on the other side of the stream, and Massena, with his back to the new danger, was approaching Porcile. But the fire of a deployed regiment stopped the head of the Austrian column ; Massena, turning about, cut into its flank on the dike; and Augereau, gath ering force, was approaching Arcola from the south. The bridge and the village were evacuated soon afterwards, and Massena and Augereau began to extend in the plain beyond. But the Austrians still sullenly resisted. It was at this moment that Bonaparte se cured victory by a mere ruse, but a ruse which would have been unprofitable and ridiculous had it not been based on his fine sense of the moral conditions. Both sides were nearly fought out, and he sent a few trumpeters to the rear of the Austrian army to sound the charge. They did so, and in a few minutes the Austrians were streaming back to San Bonifacio. This ended the drama of Arcola, which more than any other episode of these wars, perhaps of any wars in modern history, centres on the personality of the hero. It is said that the French fought without spirit on the first day, and yet on the second and third Bonaparte had so thoroughly imbued them with his own will to conquer that in the end they prevailed over an enemy nearly twice their own strength.The climax was reached just in time, for on the i 7th Vaubois was completely defeated at Rivoli and withdrew to Peschiera, leaving the Verona and Mantua roads completely open to David ovich. But on the 19th Bonaparte turned upon him, and com bining the forces of Vaubois, Massena and Augereau against him, drove him back to Trent. Meantime Alvintzi returned from Vi cenza to San Bonifacio and Caldiero (Nov. 21), and Bonaparte at once stopped the pursuit of Davidovich. On the return of the French main body to Verona, Alvintzi finally withdrew, Wurmser, who had emerged from Mantua on the 23rd, was driven in again, and this epilogue of the great struggle came to a feeble end because neither side was now capable of prolonging the crisis. In Jan. 1797 Alvintzi renewed his advance with all the forces that could be assembled for a last attempt to save Mantua. At this time 8,000 men under Serurier blockaded Mantua. Massena (9,000) was at Verona, Joubert (Vaubois' successor) at Rivoli with 1o,00o, Au gereau at Legnago with 9,000. In reserve were Rey's division (4,000) between Brescia and Montechiaro, and Victor's brigade at Goito and Castelnuovo. On the other side Alvintzi's location was the reverse of that in the previous campaign, for while he had 9,00o men under Provera at Padua, 6,000 under Bayalic at Bassano, he himself with 28,000 men stood in the Tirol about Trent. This time he intended to make his principal effort on the Rivoli side. Provera was to capture Legnago on Jan. 9, and Bay alic Verona on the 12th, while the main army was to deliver its blow against the Rivoli position on the 13th.

Rivoli.

The first marches of this scheme were duly carried out, and several days elapsed before Bonaparte was able to dis cern the direction of the real attack. Augereau fell back, skirm ishing a little, as Provera's and Bayalic's advance developed. On the 11th, when the latter was nearing Verona, Alvintzi's leading troops appeared in front of the Rivoli position. On the 12th Bayalic, weakened by sending reinforcements to Alvintzi, made an unsuccessful attack on Provera, farther south, remaining inactive. On the 13th, Bonaparte, still in doubt, launched Mas sena's division against Bayalic, who was driven back to San Boni facio ; but at the same time definite news came from Joubert that Alvintzi's main army was in front of La Corona. From this point begins the decisive, though by no means the most intense or dra matic, struggle of the campaign. Once he felt sure of the situa tion Bonaparte acted promptly. Joubert was ordered to hold on to Rivoli at all costs. Rey was brought up by a forced march to Castelnuovo, where Victor joined him, and ahead of them both Massena was hurried on to Rivoli. Bonaparte himself joined Joubert on the night of the 13th. There he saw the watch-fires of the enemy in a semicircle around him, for Alvintzi, thinking that he had only to deal with one division, had begun a widespread enveloping attack. The horns of this attack were as yet so far distant that Bonaparte, instead of extending on an equal front, only spread out a few regiments to gain an hour or two and to keep the ground for Massena and Rey, and on the morning of Jan. 14, with io,000 men in hand against 26,000, he fell upon the central columns of the enemy as they advanced up the steep broken slopes of the foreground. The fighting was severe, but Bonaparte had the advantage. Massena arrived at 9 A.M., and a little later the column of Quasdanovich, which had moved along the Adige and was now attempting to gain a foothold on the plateau in rear of Joubert, was crushed by the converging fire of Joubert's right brigade and by Massena's guns, their rout being completed by the charge of a handful of cavalry under Lasalle. The right horn of Alvintzi's attack, when at last it swung in upon Bonaparte's rear, was caught between Massena and the advancing troops of Rey and annihilated, and even before this the dispirited Austrians were in full retreat. A last alarm, caused by the appearance of a French infantry regiment in their rear (this had crossed the lake in boats from Salo), completed their demoralization, and though less than 2,00o had been killed and wounded, some 12,000 Austrian prison ers were left in the hands of the victors. Rivoli was indeed a moral triumph. After the ordeal of Arcola, the victory of the French was a foregone conclusion at each point of contact. Bonaparte refrained from striking so long as his information was incomplete, but he knew now from experience that his covering detachment, if well led, could not only hold its own without assistance until it had gained the necessary information, but could still give the rest of the army time to act upon it. Then, when the centre of gravity had been ascertained, the French divisions hurried thither, caught the enemy in the act of manoeuvring and broke them up. And if that confidence in success which made all this possible needs a special illustration, it may be found in Bonaparte sending Murat's regiment over the lake to place a mere 2,000 bayonets across the line of retreat of a whole army. Alvintzi's manoeuvre was faulty neither strategically in the first instance, nor tactically as regards the project of enveloping Joubert on the 14th. It failed because, apart from Bonaparte's genius, Joubert and his men were better soldiers than their Austrian opponents, and because a French divi sion could move twice as fast as an Austrian division, and from these two factors a new form of war was evolved, the essence of which was that, for a given time and in a given area, a small force of the French should engage and hold a much larger force of the enemy.The remaining operations can be very briefly summarized. Pro vera, still advancing on Mantua, joined hands there with Wurmser, and for a time held Serurier at a disadvantage. But hearing of this, Bonaparte sent back Massena from the field of Rivoli, and that general, with Augereau and Serurier, not only forced Wurmser to retire again into the fortress, but compelled Provera to lay down his arms. And on Feb. 2, 1797, Mantua, and with it what was left of Wurmser's army, surrendered. The campaign of 1797, which ended the war of the First Coalition, was the brilliant sequel of these hard-won victories. Austria had decided to save Mantua at all costs, and had lost her armies in the attempt, a loss which was not compensated by the "strategic" victories of the archduke. Thus the Republican "visitation" of Carinthia and Carniola was one swift march—politically glorious, if dangerous from a purely military standpoint—of Bonaparte's army to the Semmering. The archduke, who was called thither from Germany, could do no more than fight a few rearguard actions and make threats against Bonaparte's rear, which the latter, with his usual "tact," ignored.

On the Rhine, as in 1795 and 1796, the armies of the Sambre and-Meuse (Hoche) and the Rhine-and-Moselle (Moreau) were opposed by the armies of the Lower Rhine (W'erneck) and of the Upper Rhine (Latour). Moreau crossed the river near Strasbourg and fought a series of minor actions. Hoche, like his predecessors, crossed at Dusseldorf and Neuwied and fought his way to the Lahn, where for the last time in the history of these wars, there was an irregular widespread battle. But Hoche, in this his last campaign, displayed the brilliant energy of his first, and delivered the "series of incessant blows" that Carnot had urged upon Jour dan the year before. Werneck was driven with ever-increasing losses from the lower Lahn to Wetzlar and Giessen. Thence, pressed hard by the French left wing under Championnet, he re tired on the Nidda, only to find that Hoche's right had swung completely round him. Nothing but the news of the armistice of Leoben saved him from envelopment and surrender. This gen eral armistice was signed by Bonaparte, on his own authority and to the intense chagrin of the Directory and of Hoche, on April 18, and was the basis of the peace of Campo Formio.