The Apples - Family Rosaceae

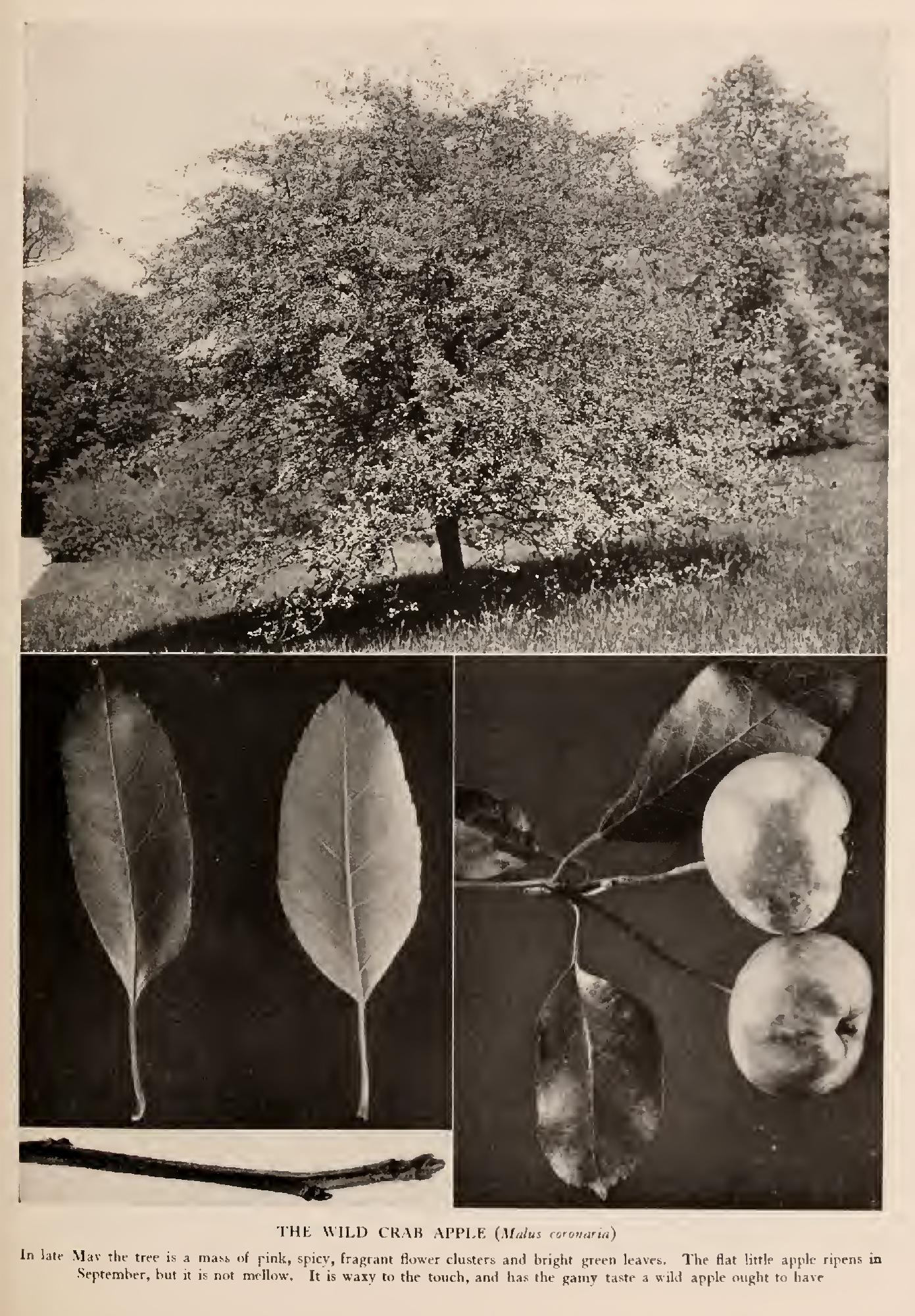

Well-meaning horticulturists have tried what they could do toward domesticating this Malus coronaria. The effort has not been a success. The fruit remains acerb and hard; the tree declines to be "ameliorated" for the good of mankind. Isn't it, after all, a gratuitous office ? Do we not need our wild crab apple just as it is, as much as we need more kinds of orchard trees ? How spirited and fine is its resistance! It seems as if this wayward beauty of our woodside thickets considered that the best way to serve mankind was to keep inviolate those charms that set it apart from other trees and make its remotest haunt the Mecca of eager pilgrims every spring.

The wild crab apple is not a tree to plant by itself in park or garden. Plant it in companies on the edge of woods, or in obscure and ugly fence corners, where there is a background, or where, at least, each tree can lose its individuality in the mass. Now, go away and let them alone. They do not need mulching nor pruning. Let them gang their ain gait, and in a few years you will have a crab-apple thicket. You will also have succeeded in bringing home with these trees something of the spirit of the wild woods where you found them.

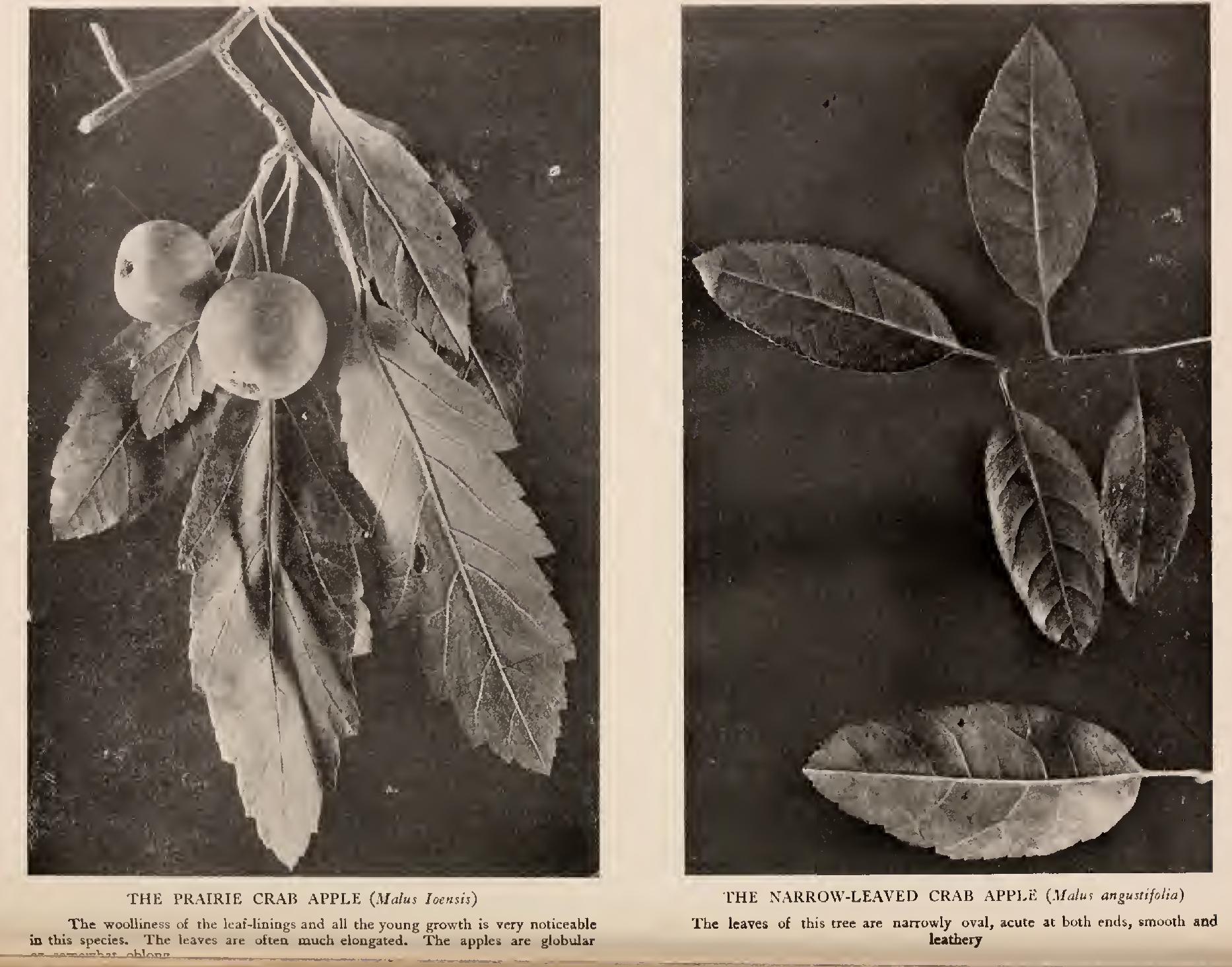

The Crab Apple (Malus angustifolia, Michx.), smaller in all its parts than the common wild crab apple, but closely resembling it in all but its leaf, is found on the Atlantic coast from New Jersey to Florida, and west to the Mississippi. It extends also to western Pennsylvania and eastern Tennessee, overlapping the range of the other species in these regions. Its leaves are leathery, almost evergreen, dark and shiny, with dull, often fuzzy linings. They are small, narrow, and blunt pointed at both ends.

The Oregon Crab (Malus rivularis, Rcem.), a white flowered species with ovate, taper-pointed leaves, grows in dense thickets along streams in the coast region from northern California well into Alaska. Its young growth is covered with a grey pubescence. The apples are oblong, rarely over inch long, and few people beside Indians consider them worth gathering foc food.

The Prairie Crab Apple (Malus loensis, Britt.) is the species found from Wisconsin to Oklahoma. It has only recently been distinguished from M. coronaria, which its flowers closely resemble. Its leaves are shorter and oval in shape, with deep, irregular teeth, and linings of silky white down. The dull green apples are of good size, larger than the other native crabs, and are not at all flattened. It is the woolliness of all the young growth in summer that will chiefly distinguish this tree.

The double-flowered form of this crab apple, Malus loensis fore pleno, is one of the most beautiful of ornamental trees. Its flowers are not so numerous as to overload the tree, and each blossom, in its setting of green leaves, has all the delicacy of a pink tea rose, exquisite in form, in shading, and in fragrance.

The Soulard Apple (Malus Soulardi, Britt.) may con fuse us. It is a hybrid of M. loensis and the common apple, as caped from orchards—the trees that come from apple seeds and are not grafted. Such are our good-for-nothing roadside "wilding" trees, with gnarly fruit nobody can eat.

The Soulard apple occurs locally from Minnesota to Texas. It is large leaved and stout of stature, with pink-flushed blossoms, like an orchard apple tree. But its woolly surfaces are often roughly rusty; its fruit is a flat crab apple on a stout stem, larger, sweeter and more edible than one expects it to be. Because this species is hardy and disposed to vary and improve in the quality of its fruit in cultivation, horticulturists consider it a distinctly promising apple for the coldest of the prairie states. Several varieties have already been produced from it.

The Wild Apple (Malus Mains, Britt.), native to southern Europe and Asia, is the parent of our cultivated apples. It is the apple of classical literature, inseparably associated with the growth of civilisation, and cultivated for the improvement of its fruit for unnumbered centuries. Our orchard trees, which renew their youth every spring in fuzzy leaves and fragrant pink and white blossoms, are direct descendants of this ancient species. Myth and folk-lore and written history all tell how this fruit, more than any other—the simple, wholesome, uncloying fruit of the north temperate zone—is interwoven with the life of the people. Read in the Song of Solomon: "As the apple tree among the trees of the wood, so is my beloved among the sons." And as a symbol of exquisite joy attained through the senses, "the smell of apples" is named with the odours of spikenard and camphire and bundles of myrrh. Read the classics, ancient and modern. Fancy the story of the fall of Troy or the legend of William Tell with the apple left out! If we would know what this wild European apple is like we may get a good idea by planting an apple seed, and watching the tree that springs from it. Or we may save time by examining a wilding tree in the fence corner, planted perhaps by the hand that threw away an apple core years ago. Suppose it was the seed of a fine desert variety of apple. Its offspring will not bear the same variety and quality of fruit. It is almost sure to "revert to the wild type." That is, the fruit of it will be small, sour and gnarly, just such apples as the orchard tree would have borne if it had not been grafted or budded while it stood in the nursery row.