The Beeches - Family Fagaceae

From now on the life of a little beech is just like that of a twig on an older tree. The opening of the long, pointed buds is a sight worth watching. If one has nct time to go to the tree every day in spring he may bring in some lusty twigs, put them in a jar of water in a sunny window, and see the whole process exactly as it happens on the tree.

Each bud loosens and lengthens its many thin bud scales and a leafy shoot is disclosed which elongates rapidly. Daily measure ments will show a wonderful record for the first few days.

As the scales drop off a band of scars appears on the base of the shoot, like the thread of a small screw. When the last of the scales has fallen this band may be half an inch wide. Each such band on a twig means the casting off of the bud scales—the begin ning of a year's growth. Counting down from the tip of any twig, the age may be accurately read. Add one year as each scar band is passed. Often the band is quite as wide as the length of the season's growth.

It is plain to see that the leaves in the opening buds were all made and put away over winter, and that they have only to grow. As the shoot lengthens the outer scales fall, and each leaf is seen to have its pair of special attendant scales, each edged with an overhanging fringe. The leaf itself is plaited in fine folds like a fan to fit into the narrow space between the scales. Each rib that radiates from the midrib bears a row of silky hairs which overlap its neighbour's, so that each side of each leaf is amply protected by a furry cover. As the leaf spreads itself it gradually becomes accustomed to the air and the sunshine, and the protecting hairs disappear. Occasionally a leaf that is in a shaded and pro tected situation on the tree may keep its hairs on the ribs until midsummer.

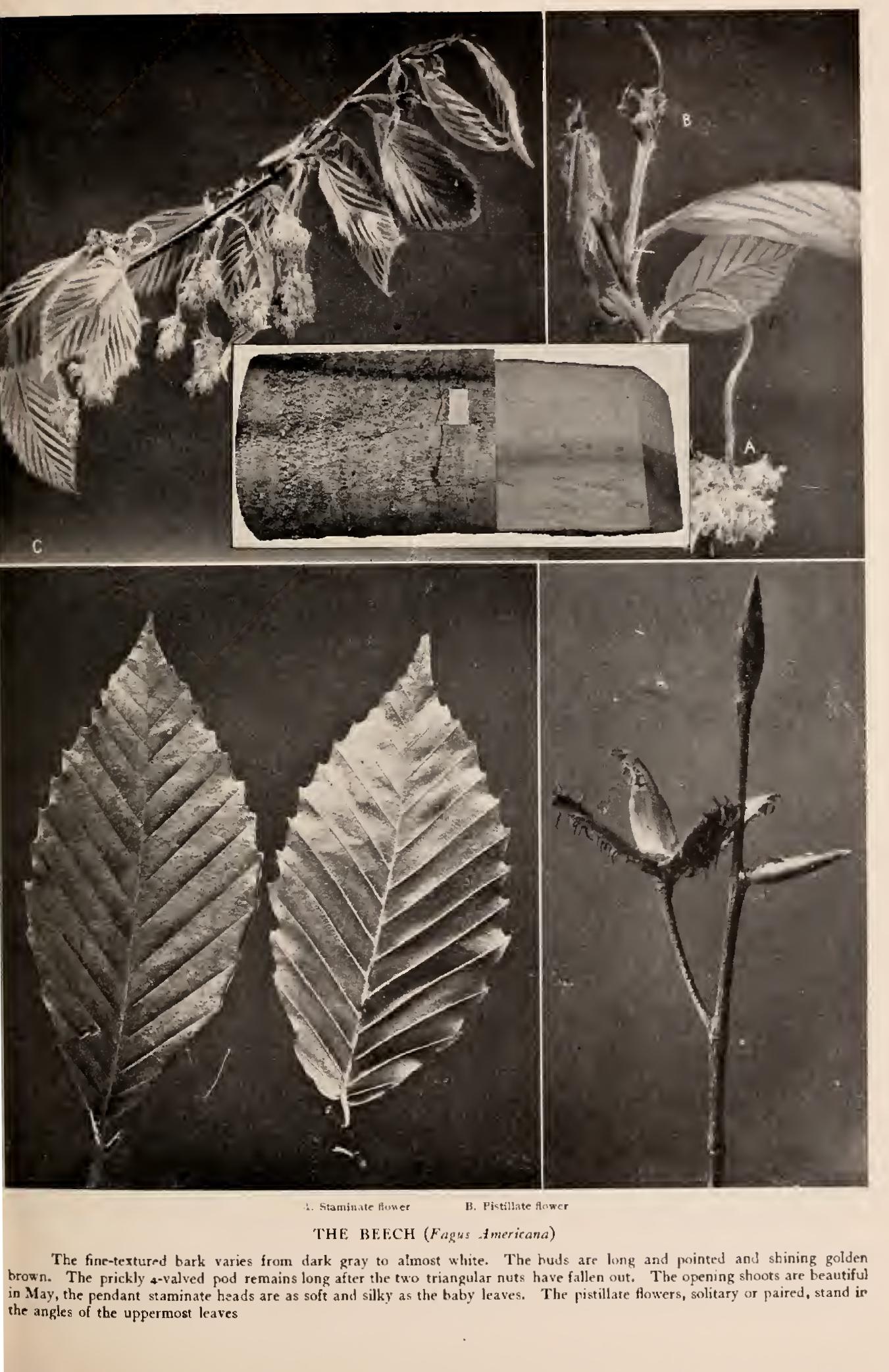

As the leaves lift themselves into independent life the blossoms of the beech appear. Few people see them. The staminate ones are in little heads swung on slender stems. When they shed their yellow pollen they fall off. In twos the pistillate flowers hide near the ends of twigs. Those which catch pollen on their extruded tongues "set seed" and mature into the triangular nuts, two in each of the burs. Early in the autumn the burs open and the nuts fall, to the great delight of boys and girls as well as the little people of the woods. Though small, the nuts are very rich and fine in flavour.

The beech is the most elegantly groomed of all the trees of the woods. Its rind is smooth, close knit and of soft Quaker grey,

sometimes mottled and in varying shades, and decorated with delicate lichens. The limbs are darker in colour, and the brown twigs, down to their bird's-claw buds, shine as if polished. Through the long summer the beech is beautifully clad; its leaves are thin and soft as silk. Few insects injure them, and they resist tearing by the wind. In the autumn the first touch of frost turns their green to gold, and they cling to the twigs until late in winter. Young trees in sheltered places hold their leaves longest.

The European Beech (F. sylvatica, Linn.) is one of the most important timber trees of Europe, and the parent of the purple and weeping beeches and other ornamental horticultural forms in cultivation in European and American parks and private grounds. It grows to noble size and form in America, distin guished chiefly by the darker colour of its bark from the native species. At home from middle Europe south and east to the Caucasus, the beech is much used as a dooryard tree; it grows famously in England, their beeches being the pride of many English estates.

Pure forests of beech are often seen in Germany and Den mark. The lumber is hard and heavy, one of the most important hard woods of the Continent. The multitude of its uses prevents a complete list. Beech bark with hieroglyphics cut in it bore messages between tribes, friendly and belligerent, in the earliest times. Beechen boards preserved the first records. These were the primitive books of northern Europe. From beech to buch is not a long etymological step in the Teutonic languages. Book is a lineal descendant of the Anglo-Saxon word bete, the name of this tree. There are those who derive the words beaker through Becher, a drinking cup, from the same old tree root. Justification is found in the fact that bowls and other household utensils were made of beech wood because they could be depended upon not to leak.

Beech nuts furnished, in ancient times, a nutritious article of human food, and an oil used for lamps, quite as sweet and good for cooking and table use as olive oil. Fagus (Gr. phagein, to eat) means "good to eat." Beech leaves furnished forage for cattle, and were dried and used to fill mattresses. Evelyn vows he never slept so sweetly as on a bed of beech leaves. The idea is certainly an attractive one, and worth carrying out.