The Chestnuts - Family Fagaceae

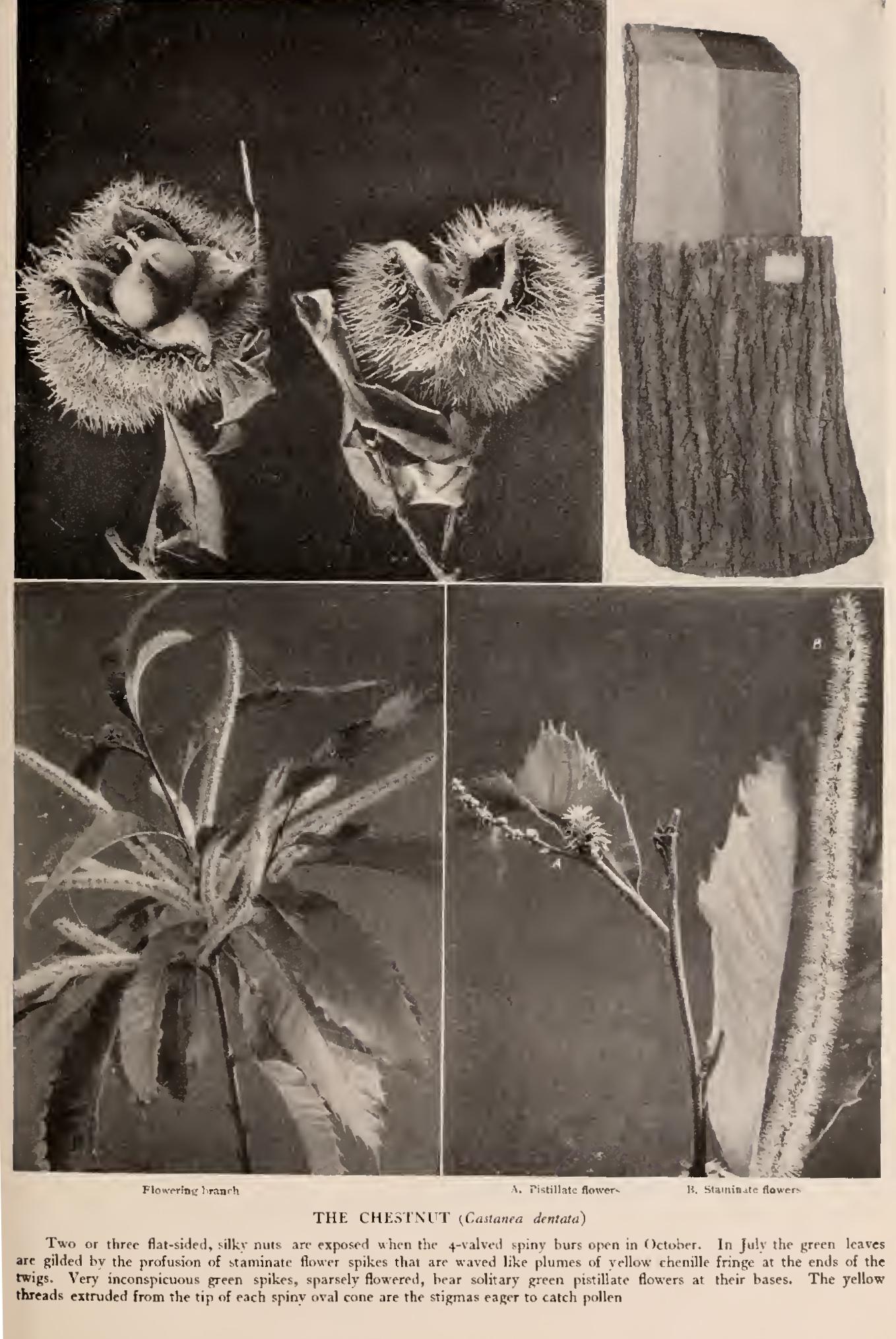

The chestnut tree turns to gold again in autumn, and the naked tree stands "knee-deep" in its own leaves all winter. Then its massive trunk, with deep furrowed bark, and the multitude of horizontal branches, striking out from the short central shaft, are distinctly etched against the sky. The small limbs are numer ous and contorted, the lower boughs often drooping. Few trees are more attractive in winter.

Chestnuts are among the trees of longest life and greatest trunk diameter. The famous giant at the foot of Mount /Etna, the "Chestnut of a Hundred Horsemen" (because it sheltered them all at one time), had a diameter of over Oo feet, and lived to be 2,000 years old. Though hollow, and with its shell in five parts when measured, records showed that a century before it had been a continuous cylinder. Each year these decaying stems wore a crown of green, until an eruption of the volcano destroyed the tree.

In our woods old chestnut stumps 6 feet in diameter and more stand covered with moss and lichens and crumbling to decay, while a circle of fine young trees, each tall and slender, with a diameter of a foot or less, have sprung up from the roots of the old tree. Specimens io feet in diameter were not unusual in the virgin forests, though the tallest ones were usually more slender.

The tannic acid in chestnut wood is what preserves it from decay in contact with the soil. Because of its durability it is largely cut for railroad ties and posts. It is well worthy of culti vation as a lumber tree. In woodwork and furniture chestnut is almost as handsome as oak. The chestnut is a valuable nut tree. Had it none of these merits it would still be saved from the saw in many instances because the landscape can ill afford to lose a fine old chestnut tree.

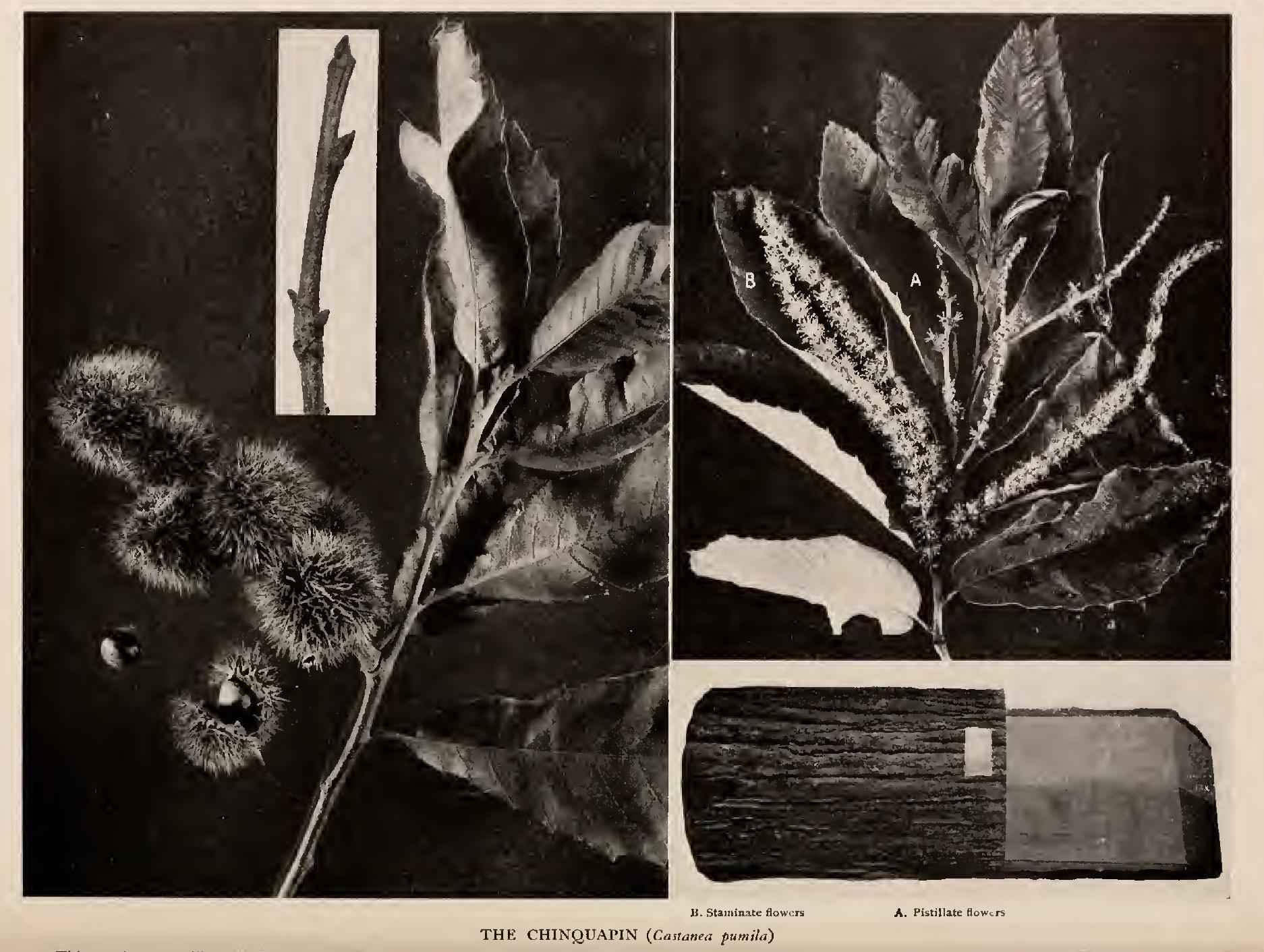

The Chinquapin (C. pumila, Mill.) is the chestnut in minia ture—rarely a tree of medium height and spreading habit—usually a shrub that seizes the land by its suckering roots, and forms thick ets on hillsides and bare ridges or on the margins of swamps. It

is found from Pennsylvania to Florida, and west to Arkansas and Texas. It grows to be a tree west of the Mississippi River, reach ing its greatest size and abundance in Arkansas and Texas. The leaves, flowers and nuts proclaim this tree's close kinship with the chestnut. A single ovoid nut with sweet kernel is contained in the globular spine husk. These are found in autumn in the markets of Southern cities.

The chinquapin grows lustily and fruits abundantly on a rocky bank in the Arnold Arboretum at Boston. This proves its hardiness far north of its natural range, and a sight of this thicket (or any other like it) must convince anyone that it is an orna mental shrub worthy of introduction into parks and private estates.

Where the chinquapin grows large it is used for railroad ties and fence posts. Its wood has the qualities of chestnut lumber, but is heavier.

2. Genus CASTANOPSIS, Spach.

The Golden - leaved Chestnut (Castanopsis chrysophg A. DC.), also called chinquapin, seems to be a connecting link between chestnuts and oaks. One American species represents the large genus which is widely distributed through Asia. Our tree grows from Oregon south along the mountain slopes that face toward the Pacific Ocean. In northern California it is one of the splendid trees of the coast valleys, often above too feet in height, with sturdy trunk supporting a broad, dense, rounded dome. The glory of the tree is its dark, lustrous foliage, lined with a yellow scurf. The leaves persist for two or three years, turning yellow before they fall. Thus the twigs are always decked with green and gold. The flowers are much like those of the chinquapin of the South; the sweet nut protrudes from a cup, or saucer, thickly set with long spines. One hardly knows whether to call it a chest nut bur or a spiny acorn cup. It is both—and neither. The coarse wood which resembles chestnut is sometimes used for ploughs and other implements. The bark is rich in tannin.