The Larches - Family Coniferae

The tamarack loves the Northern mountain slopes and the cold swamps of Labrador and Canada and our Northern States. It is the bravest of all the conifers, standing erect, a pitiful minia ture of its true self, on the very edge of the Arctic tundras, a line that no tree dares overstep. Its companions, the black spruce, Balm of Gilead and an Arctic willow, are prostrate at its feet. In American lawns trees 6o feet high are often seen. But compared with the European tree this one is not a horticultural success. The mark of its life struggle with adversity is on the species. Even seedlings coddled in nursery rows have sparse crowns of unsymmetrical growth. In rich soil and among lux uriant oaks and pines and thick-leaved maples the tamarack looks ragged and forlorn. It is homesick' for the cold, wet soil and the bleak wind and the valiant company of its kinsmen. It is an artistic and an ethical mistake to set one of these trees by itself. Plantations of it are justifiable.

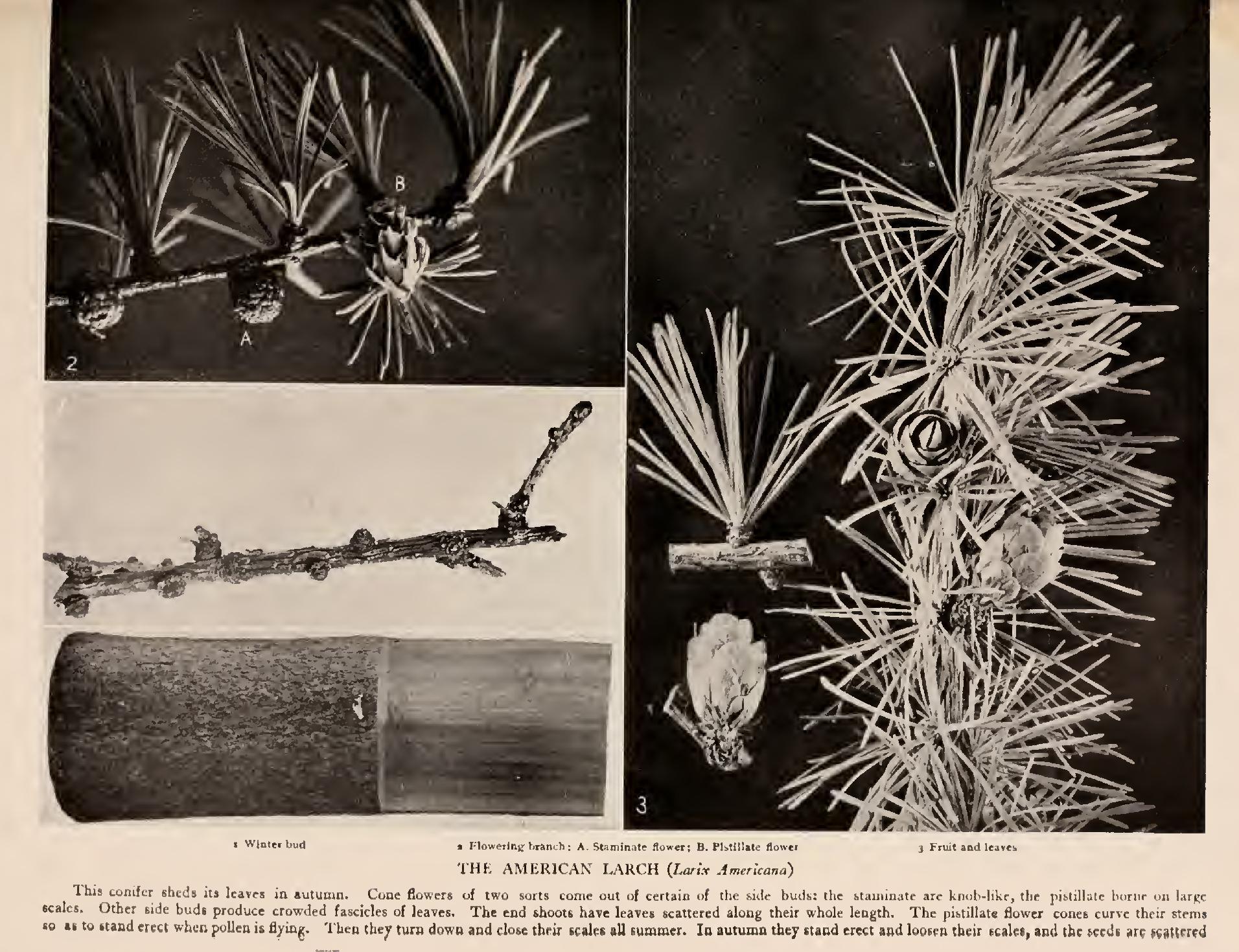

Mountain bogs too deep to measure are covered with tama rack. The fibrous roots were the Indian's thread ; tough and fine as a shoemaker's "waxed end," it sewed the canoe of birch, making a seam that scarcely needed the wax of the balsam to make it water tight. Hiawatha sang : "Give me of your roots, 0 Tamarack I Of your fibrous roots, 0 Larch Tree I My canoe to bind together So to bind the ends together That the water may not enter That the water may not wet me." The flowers of the tamarack are not conspicuous, but they repay the one who looks for them. The yellow staminate clus ters, like little powdery knobs, soon fall, but the pistillate ones, conical, with green bracts alternating with rosy scales, are beau tiful along the twig against the lettuce green of the opening foliage clusters. Erect and with scales spread, they catch the flying pollen ; then close their scales and "hang their heads " throughout the summer. Under the rosy scales the seeds are 6o growing. In autumn they wake up, turn themselves about (which seems quite ' unnecessary), and sitting quite erect on the twigs, part their brown scales,, daring the wind to capture and carry off the winged seeds. There is plenty of time, for the ripe cones remain where they are until the second year.

Western Larch (Larix occidentalis, pyramidal tree, with naked trunk and sparse foliage at the top, too to 250 feet high. Bark cinnamon-red, broken into thick plates, with thin, scaly surface. Wood heavy, hard, strong, close grained, red, durable. Buds small, globose, brown, hoary. Leaves stiff, sharp, keeled below, triangular, pale green, turning yellow in autumn. Flowers : pistillate sessile, oblong ; bracts needle pointed ; staminate stalked, yellow, globose. Fruits large, oval cones ; scales hoary at base ; bract needle pointed, shorter than scale. Preferred habitat, low, wet soil, at 2,000 to feet elevation. Distribution, southern British Columbia in

Cascade Mountains to Columbia River; in Blue Mountains of Washington and Oregon; to western Montana. Uses: Best wood among conifers. Used for furniture and interior finish, railroad ties, fence posts.

The Western larch holds an enviable rank among American forest trees. It is counted superior to all other conifers in the value of its wood, which seems to have all good qualities. Its hardness, fine colour and brilliant polish commend it to the maker of furniture. As fence posts and railroad ties it lasts indefinitely, compared with other timber. Trees 6 feet in diameter and zoo feet high are quite common in this species. Of such mighty trunks a very small outer layer is sap wood.

For the first fifty years this larch is pyramidal, but thinly branched. From this age on the lower limbs die, and the tree at length presents a bare trunk with a mere wisp of a top. What wonder that growth is slow! One log 18 inches in diameter showed 267 rings. In its fiftieth year it was but 9 inches in diameter. The last inch of wood was eighty years in forming. No other tree has so inconsiderable a foliage mass to maintain so large a body.

The brown gum that exudes from wounds in the bark of this tree seems not to be resinous, though it smells like turpen tine. It is sweet and resembles dextrine. As dextrine is a soluble form of starch, the Indians find this wax a very nutritious article of food.

The Western larch shows little merit as an ornamental tree on the eastern side of the continent. In Europe it does better, and is planted for timber as well as for ornament. I cannot grieve that this magnificent wild tree scorns to adapt itself, or even its seedlings, to the compass of a sunny suburban lawn in the East. People who truly wish to know it must go to the wild forest parks we own in the great Northwest. There waits for us with infinite patience (and an indifference quite as large), the grandest larch tree in the world! The Alpine Larch (Larix Lyallii, Parl.) is a slender tree of the high tablelands of the Northwest, balancing itself on rocky ledges, and seeming to choose the most exposed and forbidding situations. It climbs to the very limit of tree growth, and pre sents a more irregular form than either of its relatives. The tough limbs divide at intervals, throwing out several branches at the same point. These differ in strength and size. The twigs are covered with white, hairy fuzz which is shed at the end of the second winter. The bark of the twigs then darkens for a period of several years and becomes almost black. On the trunk the bark is reddish and loosely scaly. The leaves are stiff and sharp, blue-green and distinctly 4-angled. The cones have their scales far surpassed in length by the tip of the bract. The hairiness of the cones is conspicuous.