The Pitch Pines

The leaves of Pinus palustris yield by distillation an essential oil of balsamic odour that closely resembles oil of turpentine. The weaving of florists' baskets from the long, shining needles is just beginning, and is an industry that ought profitably to employ women and children in neighbourhoods. " Pine wool" is made by boiling the leaves in strong alkali, and then carding the fibres thus released. It is woven into a brown carpet somewhat like cocoa matting, and into other textile fabrics. It is an im portant stuffing for upholstery, and is a natural antiseptic dress ing for wounds.

The most conspicuous character of the longleaf pines is the great length of its flexible leaves. Next to this is the great sil very "bud" at the tip of each shoot. This is the cluster of young leaves enclosed in their subtending scales, before these crowded scales fall.

Of late a new and profitable industry has sprung up in the wake of lumbering. Stumps are cut into small sticks for kindling wood, and sold in small bundles. These sticks are rich in resin, and bring good prices. Roots, branches and other waste pieces are gathered and converted into tar or into charcoal. ' The profits that come from gathering up the fragments after the lumbermen and turpentine distillers give one an idea of what enormous values are being squandered by wantonness and ignorance. The South is rich in natural resources, but its noblest patrimony, the pine forests, seems doomed soon to be spent.

The Pine (P. Coulteri, D. Don.) is chiefly remark able for the size and weight of its cones, which are the heaviest of all the fruits of the pines. They hang like old-fashioned "sugar loaves" on the stout branches, which carry them with apparent ease, though they reach 15 to 20 inches long, and weigh 5 to 8 pounds. The scales are so thickened as to stand out from the central axis; the stout, curved beak and the thick part w ' h it surmounts remind one strongly of the head of an eagle. The seeds, which reach inch'n length, not counting the th n wing, are rich in oil and sugar. They are gathered for food by the Indians in southern California.

The leaves of this pine match the cones. They are stout and stiff, with saw-tooth edges, dark blue-green, and 6 to i6 inches long. The sh6aths at the bases of the leaves are an inch or more long, and persistent. They are tufted on the twigs and are not shed for three or four years. This fact gives the tree a

luxuriant crown, and though it does not grow over medium height, it is always a striking and picturesque figure on the western slopes of the California coast mountains.

The wood is indifferent in quality, and the tree is cut only for fuel. It is planted for its great golden-brown cones. In Europe it makes rapid growth, and fruiting trees of good size are not uncommon in France and Germany.

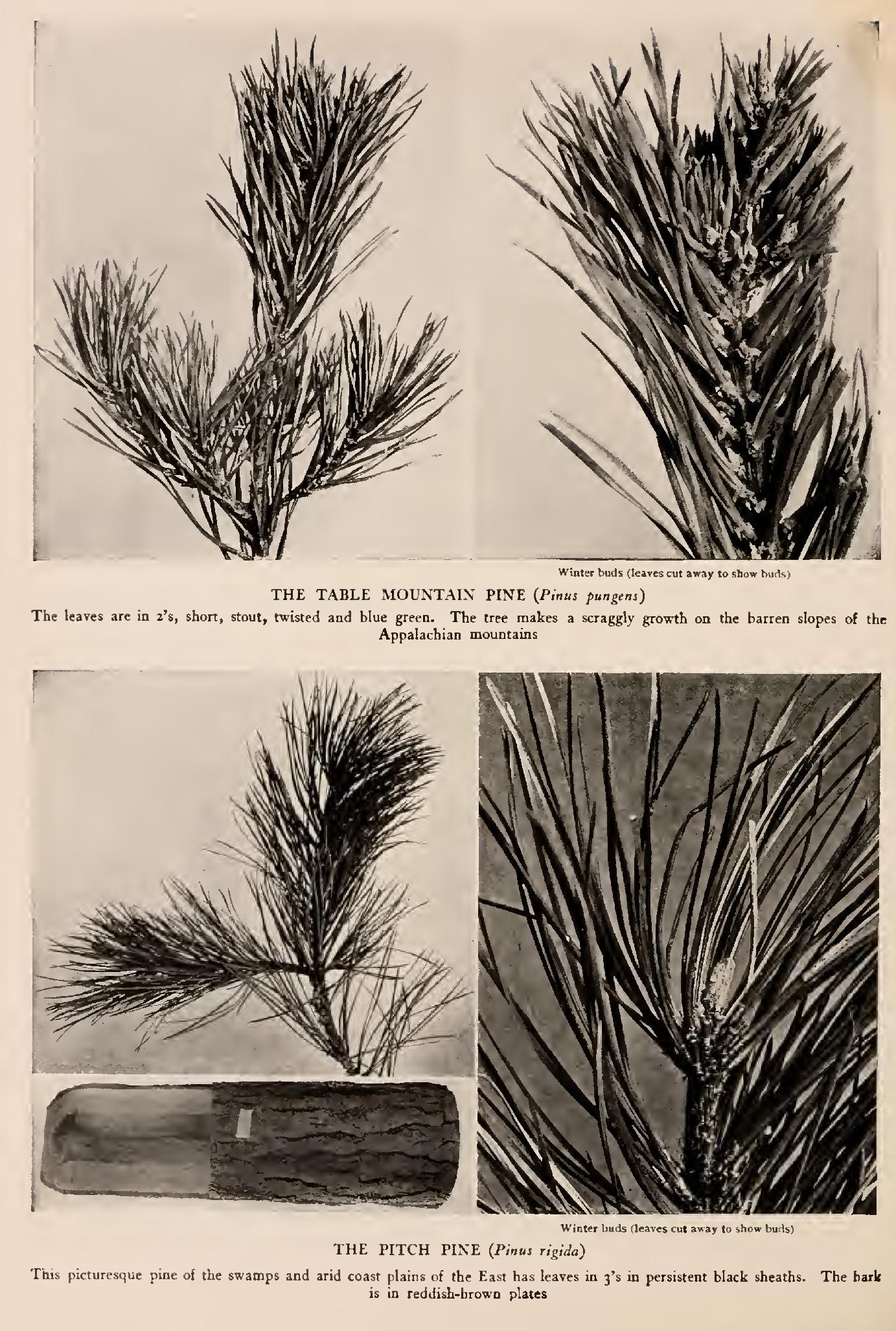

Pitch Pine (P. rigida, Mill.)—A gnarled, irregular tree 5o to 75 feet high, with short trunk and rigid, rough branches. Bark thick, broken into plates by deep, irregular fissures; scales thin; bark red or purple. Wood light red, soft, durable, brittle, coarse. Buds to inch long, reddish, with fringed scales.

Leaves in threes, rigid, stout, 3 to 5 inches long, dark yellow green; sheaths becoming black, persistent. Flowers cious; staminate short, densely clustered at base of season's shoot; pistillate lateral, in clusters, rosy tinged, oval, short stalked. Fruits biennial, t to 3} inches long, ovate, scales with sharp, recurving beaks. Preferred habitat, sandy uplands and cold swamps. Distribution, New Brunswick to Georgia; west to Ontario and Kentucky. Uses: Fuel and charcoal mak ing. Reforesting worthless land. Sparingly used as lumber.

The pitch pine carries picturesqueness to extremes, and be comes in old age grotesque, even absolutely ugly. It has the look of a tree that has been hounded by untoward circum stances. In youth the tree has a rounded, symmetrical head, formed of successive whorls of branches. In its subsequent struggles symmetry is lost, and the contorted limbs, tufted with scant, sickly-looking foliage, and studded with the squat, black, prickly cones of many years, reach out with an expression of mute appeal that tempts one to cut the tree down and end its sufferings. if it is cut, however, it sends up suckers from the roots, a strange habit among the pines; and its winged seeds spread the species over barren and shifting sand dunes, and otherwise hopelessly treeless areas. This work is so well done on the island of Nantucket and the desert soil of Cape Cod, even those areas which are washed by the spring tides, that the pitch pines have earned the regard of men. The inferior lumber is forgiven.