Joinery

surfaces, bit, material, lines, required, glue and mortise

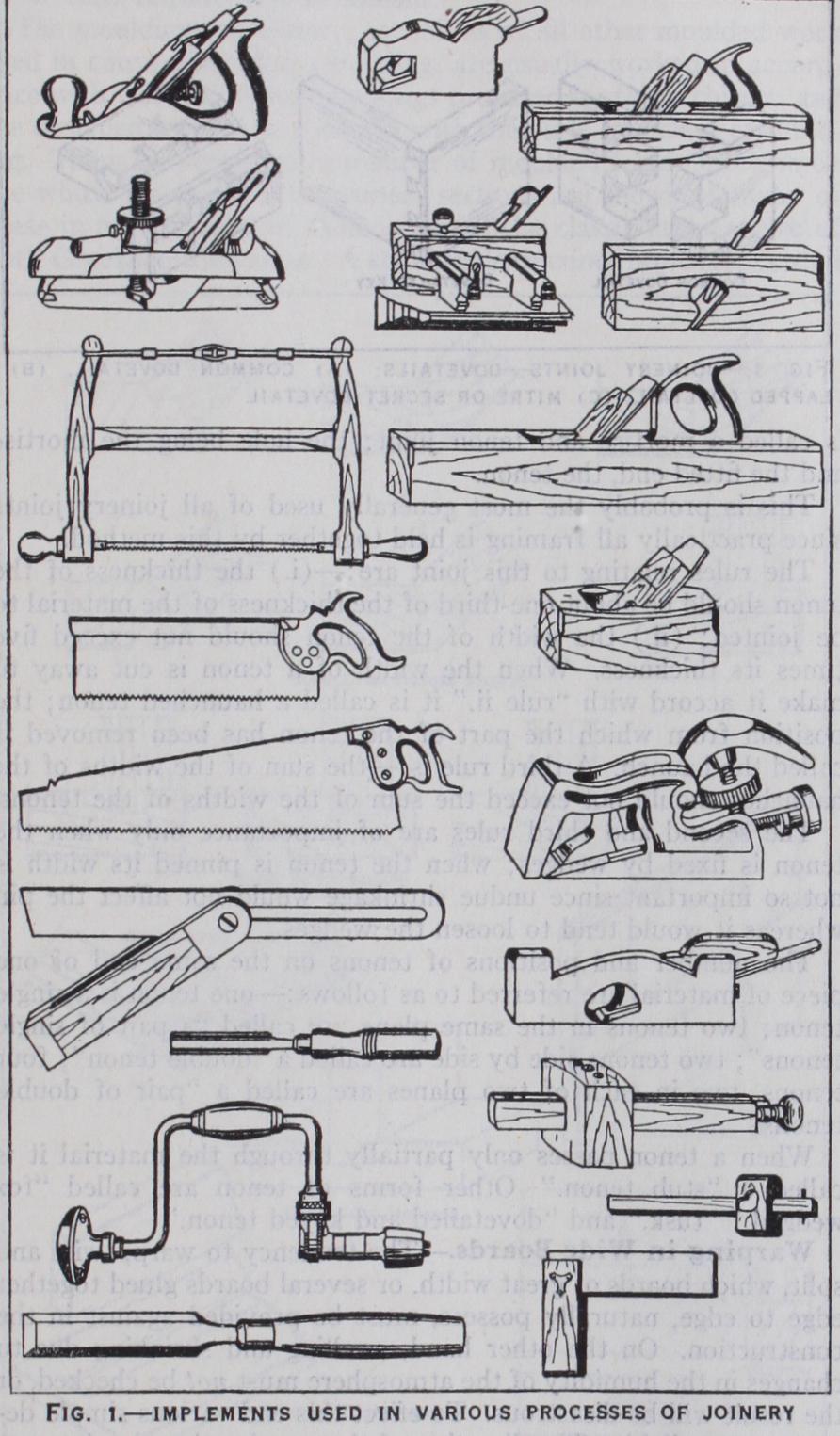

Chisels: the firmer chisel for removing waste; the paring chisel for finishing surfaces that are inaccessible or unsuited to the plane ; the mortise chisel for large mortises ; the sash chisel for small mortises.

Gouges: the firmer gouge for heavy circular cutting; the paring gouge for finishing concave curved surfaces; the scribing gouge for scribing mouldings.

Boring bits: the twist or augur bit ; the centre bit ; the center less bit ; the expanding bit ; the shell bit; the nose bit ; the gimlet bit ; twist drills ; countersinks for wood and metal.

Brace or stock:

for holding every form of boring bit.

Try squares: for testing the right angle between adjacent sur faces and for squaring lines across material.

Bevel: for testing angles other than right angles and for mark ing lines inclined to the surfaces of the material.

Gauges: the marking gauge for marking lines parallel to the surfaces of the material ; the mortise gauge for marking mortise lines on the material; the spider gauge for marking and testing curved and twisted material.

Spokeshaves:

for cleaning up and shaping curved surfaces. Mitre block and mitre box: used in sawing mitred intersections. Mitre shoot: used in planing mitred surfaces.

Cramp:

for forcing and holding surfaces into close contact. Hand screw: a form of wooden cramp.

Routers: for forming grooves in curved and twisted material and for finishing sunk surfaces.

Hammer, Mallet, Screwdriver, Bradawl, Gimlet, Pincers, Sharp ening stone and Slips: and a variety of minor tools. (See fig. I.) In making a typical example of joinery, such as a panelled door and door linings, and assuming the whole of the work to be done by hand, the chief operations and their order of procedure would be as follows :—the measurements are taken from the architect's scale and detail drawings and full size sections and special details are set out on a thin board called a setting out rod, or on paper. A quantity sheet, containing the sawn and finished sizes and the names of the various members, together with a list of the iron mongery required, is prepared. The material is then cut and planed to the required sizes, skill and great care being exercised to produce true surfaces and the required angles between the surfaces. If the width of the panels necessitates glue jointing

this operation is performed at this stage to•give time for the glue to harden before the panel is required for fitting.

The shoulder mortise and other cutting lines are then trans ferred from the rod to the material ; the important lines being marked with a scribing knife or gauge.

The mortising is then done and the tenons that are parallel to the grain (fibres) are cut by the saw.

The rebating, grooving and moulding are the next operations, after which the cheeks of the tenons are cut, the tenons haunched and the stuck mouldings (if any) scribed or mitred. The panels are then fitted and cleaned up, and all the surfaces of the framing that will be inaccessible when the work is put together are lightly planed and glass-papered. The work is next assembled and lightly cramped up for inspection. If everything is found to be satis factory the work is partially knocked apart, the glue or other adhesive is applied and the final cramping and wedging up is completed. Finally, the surfaces are finished with the plane and in the case of hardwoods, the scraper and glass-paper.

The preparation of joinery entirely by hand is now the excep tion—a fact due to the ever-increasing use of machines, which have remarkably shortened the time required to execute ordinary operations. Various machines rapidly and perfectly execute plan ing and surfacing, mortising and moulding, leaving the crafts man merely to assemble, glue and wedge. Large quantities of machine-made flooring, window-frames and doors are now im ported into England from abroad.

Joinery Woods.—The structure and properties of wood should be thoroughly understood by every joiner. Timber shrinks con siderably in the width, but not appreciably in the length; its size and sectional shape alters with changes of temperature and humidity. Owing to these changes certain joints and details, hereinafter described and illustrated, are in common use for the purpose of counteracting the bad effect of movements which would otherwise injure the joinery work.