Jupiter

planets, belts, planet, times, dark, belt and spots

JUPITER, in astronomy, the largest of the planets, and with the exception of Mars the most interesting of all for telescopic study. It revolves round the sun at a mean distance of about 5.2 times that of the earth, or 483,000,000 miles; and since its equatorial diameter is about 88,700 miles it presents a disc which at opposition attains an apparent diameter of from 44 to 50 seconds of arc. The planet requires 4,333 days (11.86 years) to complete a sidereal revolution, and its synodical period, or the mean interval between successive oppositions, is 399 days. To the naked eye Jupiter shines with a lustre second only to that of Venus among the planets and under favourable circumstances it is bright enough to cast a shadow. Its albedo is high, viz., 0.44, which means that it reflects 44% of the sunlight falling upon it. Its stellar magnitude at opposition ranges from -2.1 to -2.5. When viewed telescopically the disc of the planet is seen at once to be not circular but considerably flattened at the poles. The amount of this flattening has been determined by micrometrical measurements and theoretically, by H. Struve, from the perturba tions of the satellites by the equatorial protuberance of the planet. The probable value is not far from The mass of the planet, taking that of the earth as the unit, is nearly 32o, and since its volume is over 5,300 times that of the earth its mean density must be rather less than one quarter as great, or 5.3 times that of water.

Surface Features: Belts and Zones.

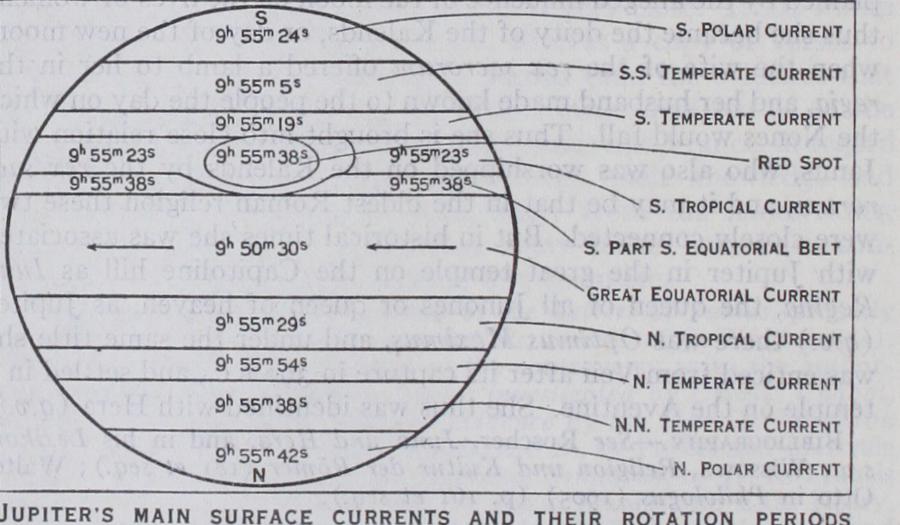

A quite small telescope will show that the disc of the planet is marked by parallel dark streaks or "belts" separated by bright spaces which are termed "zones." The belts were first detected by Nicolas Zucchi and Daniel Bartoli in May 1630, about 20 years after the discovery of the f our large satellites. Modern instruments show them to be broken up frequently into irregular markings, particularly at the edges where dark spots separated by white indentations and rifts are specially liable to occur. Isolated dark spots and brilliantly white areas are also frequently observed on the zones, together with delicate linear markings or wisps, sometimes resembling loops or festoons enclosing white spots and sometimes connecting to gether dark spots on the belts on opposite sides of the zones. Thisis especially the case with the equatorial zone. All these markings are subject to changes which may be very rapid. Occasionally a belt or portion of a belt will disappear in the course of a few weeks or months while other features develop for a time and then die out. It is quite evident that there is nothing stable or fixed about Jupiter as seen from the earth, but that what is observed is merely a shell of clouds or vapours which are often in a greatly disturbed condition. The photographs shown under PLANETS (Pl. figs. 4 & 5) give an excellent idea of the general fea tures of the disc as observed telescopically, though the fading of the light and lack of definition near the limb in conseauence of the absorbing effect of the Jovian atmosphere are much more marked photographically than to visual observation.

The planet's surface not infrequently displays striking colours. In particular the two belts north and south of the equator are sometimes very red whereas at other times they may be brown, neutral grey or even bluish. In April 5899 A. Stanley Williams, after a thorough examination of the available material accumu lated between the years 1836 and 1898, announced that these belts exhibit a periodic variation in such manner that when one belt attains a maximum of redness the other is colourless or even bluish and that between the periods of extreme coloration both belts are moderately red. The cycle of changes was found to take place in 12.08 years which is in close agreement with the period of the planet's revolution. Moreover the phase of minimum redness of a belt was found to occur shortly after the autumnal equinox of the hemisphere in which it is situated, which would seem to indicate a seasonal effect. It is hard to understand how the variations can be due to the varying tilt towards the sun of the planet's axis, the inclination of which to the plane of the orbit is only 3° 7', yet such would appear to be the case. Another point of great interest is Williams's deduction in March 192o that the equatorial zone also shows a periodic variation in colour in the course of the planet's revolution, assuming a dull orange or tawny hue shortly before the aphelion position is reached.