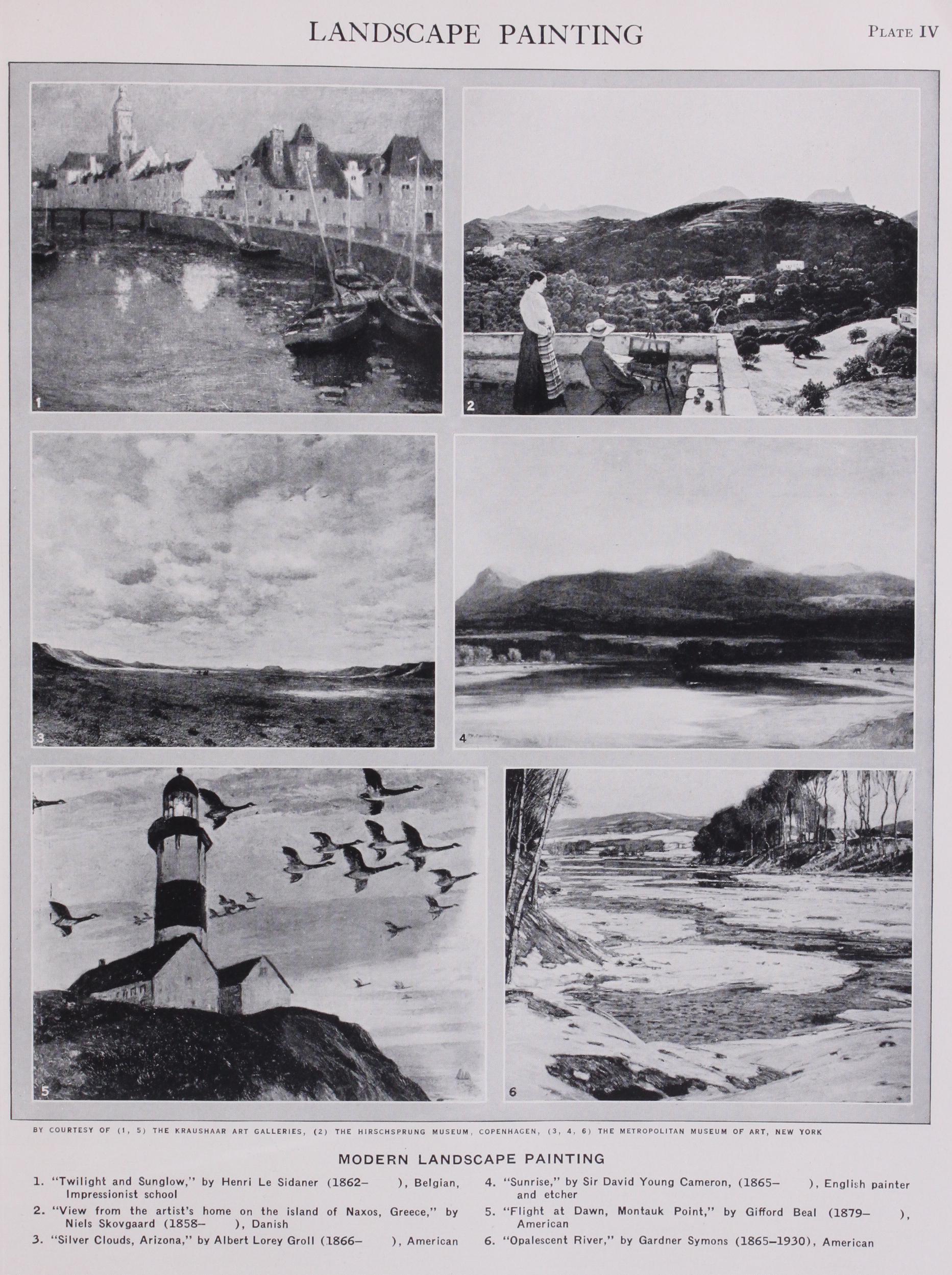

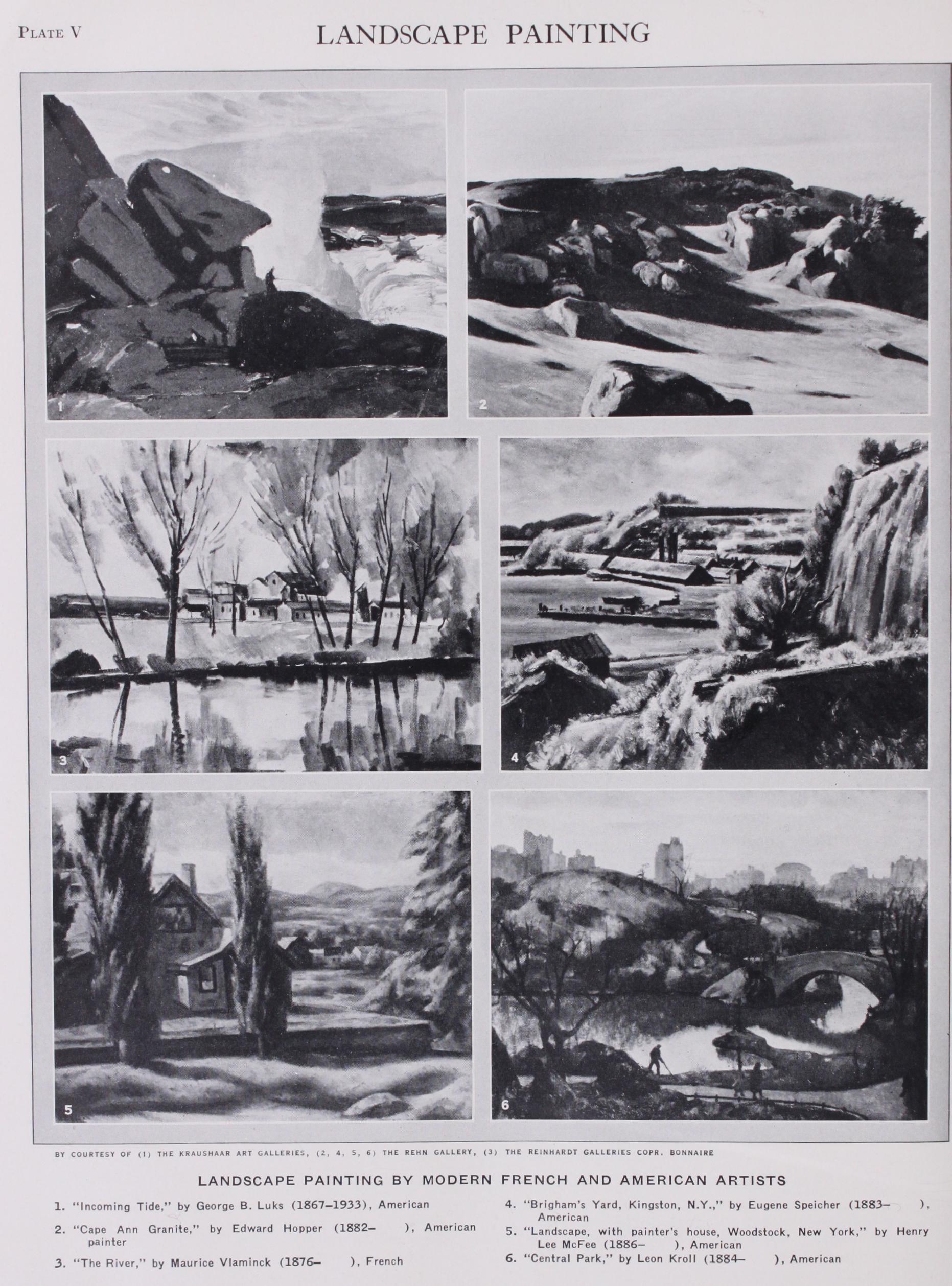

Landscape Painting

art, colour, american, to-day, qualities, painter, artists and impressionism

Impressionism was followed by Neo-Impressionism, a more formal and scientific technique of dots of pure pigment now called Pointilism. (See POST-IMPRESSIONISM.) Signac, its origi nator, said, "By means of suppression of all impure mingling, by the exclusive use of the optical mingling of pure colours, it guar antees a maximum of luminosity, colouration and harmony." Seurat, Henri Martin, Auguste Pointilin and Fjaestad of Sweden employed this manner in painting.

In Italy Segantini was one of the greatest artists of the 19th century. In one respect, he is unique; he demonstrates more than any other artist the unwillingness to be influenced by any "isms" or methods, and the value of independent, individual thinking and feeling. He did not strive in the least to live in his age with the hope of being classified with the artists who expressed the ideas and feelings current in their age. Segantini's life was solitary and his thought independent. His chaste passion for his art has made his work very virile and gives it great depth of feeling.

After Neo-Impressionism came Post-Impressionism. The mo mentary emotion of the Impressionist was dissatisfying to some artists of earnest effort and a new leadership was established by the work of Cezanne, Van Gogh and Gauguin. Its cult was that the artist should endeavour to master his subject rather than that his subject should master him. Cezanne's aim seems to have been to find a greater measure of volume, depth and height than Impressionism achieved. He ruthlessly eliminated detail, thus seeming to return to primitive art.

Other Artists.

Gauguin did not begin to paint until he was 35 years old. His desire to paint was combined with his disgust for the civilized world. He worked at times in Brittany but is famous for his landscape decorations of Tahiti which have a jewel-like splendour of colour and an expression of mass. Van Gogh had a great power of perception but his impetuosity and lack of restraint made him seem a very brutal if very powerful painter. His ploughed fields are so interpreted as to make one feel and smell the pungent turf, as one almost smells his blos soming trees. His colour is very glowing and powerful.

America.

Rodin wrote of American landscape as he knew it : "There is in America a renaissance of landscape painting equalled only by the Italian Renaissance." The aspect of American land scape is influenced less by European art than is figure painting. All its best landscape painters are distinctly American ; George Inness, Homer Martin, Winslow Homer, J. Alden Weir andWillard Metcalf were all distinguished American landscapists. (See PAINTING; WATER-COLOUR PAINTING; OIL PAINTING.) Landscape painting of the present century has been the subject of a great number of conflicting influences. Of these the first and greatest was undoubtedly Impressionism (q.v.). Few are the out door painters of to-day who have not been profoundly influenced by the discoveries of the group of Frenchmen who devoted them selves to the study and interpretation of the phenomena of light. But, while Monet, Monet, Sisley and their compatriots sacri ficed form in their search for vibration, the outdoor painter of to-day has increasingly concerned himself with it. Indeed, form, or the allied problem of mass—three-dimensional form—is the particular concern of the followers of Cezanne and form in the sense of design is the greatest interest of many of the other so called "Modernists," many of whom, be it said in passing, seem to believe that it originated with them.

A painter who is devoting himself to the exploiting of a certain quality in art, be it form or colour or design or some esoteric and not easily defined subtlety, almost inevitably disregards in his work the other qualities in which, for the moment, he is not in terested. This was markedly true in the case of the Impression ists. It is evidenced to-day by a multitude of painters who are attempting to introduce new qualities into their art or to employ it for the expression of hitherto unexpressed emotions and who, in the attempt, are quite regardless of the ordinary technical qualities. It is for this reason that much of this experimental work is crude. Unfortunately for its creator the crudities are frequently more obvious than are the subtle qualities for which he is striving and which, in some measure, he may have realized.

The experimental in art was never more in evidence than in the era of reconstruction through which we are passing to-day. The landscape painter is no longer interested in producing a transcript of nature ; he is not moved by the once important tech nical problems but only by the desire to produce balanced design of form and colour. Even the jargon has changed. Instead of "values" he talks of "rhythms" and his critical compatriots ques tion not the factual truth of his colour but his reasons for employing it in certain arbitrary forms and relations.