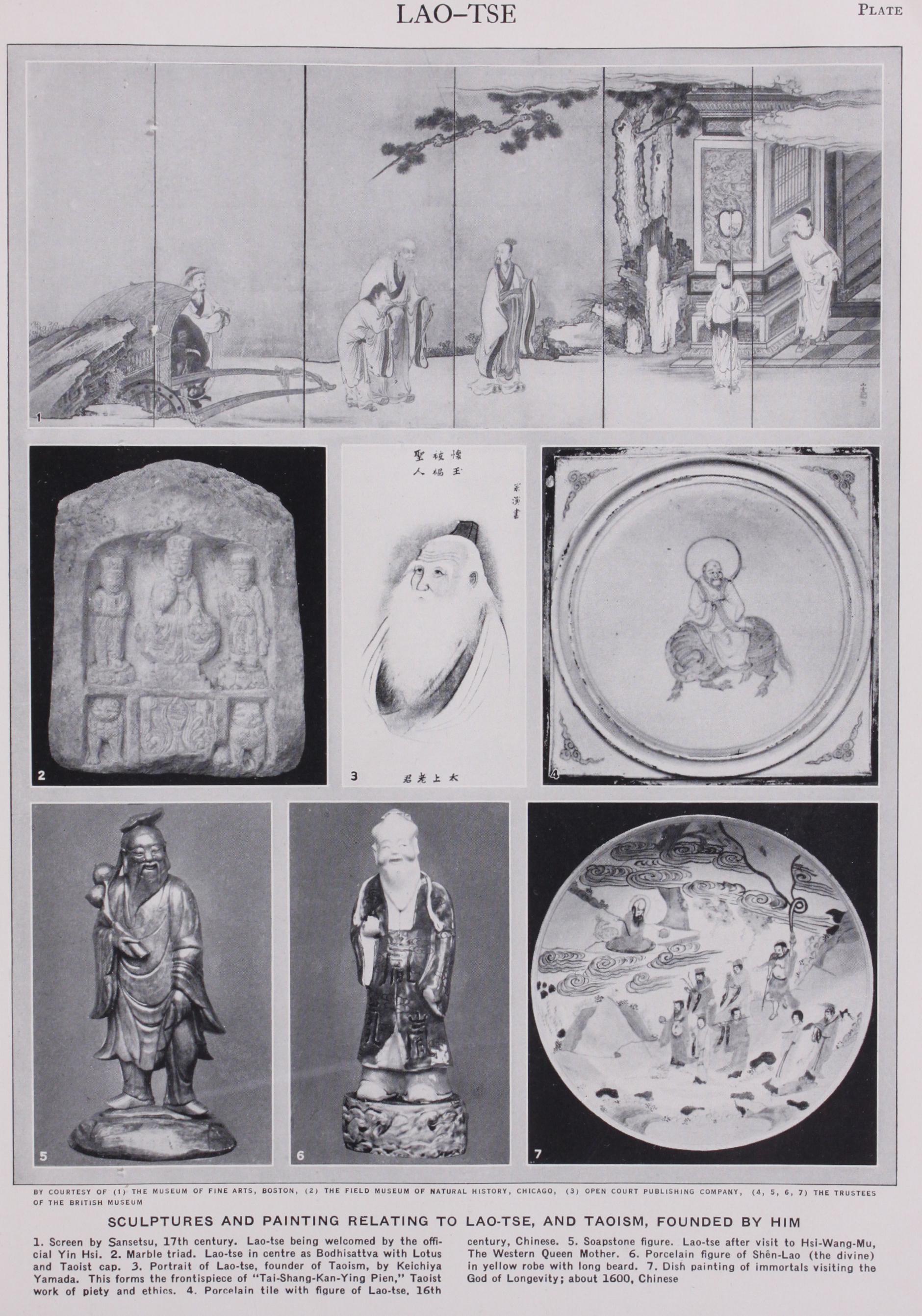

Lao-Tse

tao, word, confucius, quality, bc, hundred, li, virtue, free and government

LAO-TSE (properly LA0-'110), the designation of Li Erh, a pre-Confucian philosopher and metaphysician of China. The Tdo—te—king or Classic of Reason and Virtue, commonly ascribed to him was obviously not from his brush although it embodies his precepts and speculations. Lao-tze means the "Old According to the Shan Hsien Chiian the mother of Lao-tze, after a supernatural conception, carried him in her womb sixty-two years (or seventy-two, or eighty-one), so that, when he was born at last, his hair was white as with age.

All that Isil-ma Ch'ien tells us about Lao-tze goes into small compass. His surname was Li, and his name Erh. He was a native of the state of and was born in a hamlet not far from the present prefectural city of Kwei-te in Ho-nan province. He was one of the recorders or historiographers at the court of Chow, his special department being the charge of the whole or a portion of the royal library. He must thus have been able to make himself acquainted with the history of his country. The year of his birth is often said, though on what Chinese authority does not appear, to have taken place in the third year of King Ping, corre sponding to 604 B.C. That date cannot be far from the truth. That he was contemporary with Confucius is established by the con current testimony of the Li Ki and the Kid FT/ on the Confucian side, and of Chwang-tsze and Sze-ma Chien on the Taoist. The two men whose influence has been so great on all the subsequent generations of the Chinese people-Kung-tsze (Confucius) and Lao-tse-had perhaps one interview, in 517 B.C., when the former was in his thirty-fifth year. Lao was in a mocking mood; Kung appears to the greater advantage. If it be true that Confucius, when he was fifty-one years old, visited Lao-tse as Chwang-tsze says (in the Tien Vun, the fourteenth of his treatises), to ask about the Tao, they must have had more than one interview. There may have been several meetings between the two in 517 B.C., but we have no evidence that they were together in the same place after that time : adds :-"Lao-tse cultivated the Tao and virtue, his chief aim in his studies being how to keep himself concealed and unknown. He resided at (the capital of) Chow; but after a long time, seeing the decay of the dynasty, he JAI it, and went away to the Gate (leading from the royal domain into the regions beyond-at the entrance of the pass of Han-kil, in the north-west of Ho-nan). Yin Hsi, the warden of the Gate, said to him, are about to withdraw yourself out of sight ; I pray you to compose for me a book (before you On this Lao-tse made a writing, setting forth his views on the tao and virtue, in two sec tions, containing more than s,000 characters. He then went away, and it is not known where he died." The historian then mentions the names of two other men whom some regarded as the true Lao tse. One of them was a Lao Lai, a contemporary of Confucius, who wrote fifteen treatises (or sections) on the practices of the school of Tao. Subjoined to the notice of him is the remark that Lao-tse was more than one hundred and sixty years old, or, as some say, more than two hundred, because by the cultivation of the Tdo he nourished his longevity. The other was "a grand his toriographer" of Chow, called Tan, one hundred and twenty-nine ( ?one hundred and nineteen) years after the death of Confucius. The introduction of these disjointed notices detracts from the verisimilitude of the whole narrative in which they occur.

Finally, Ch'ien states that "Lao-tse was a superior man, who liked to keep in obscurity," traces the line of his posterity down to the 2nd century B.C., and concludes with this important state

ment :-"Those who attach themselves to the doctrine of Lao-tse condemn that of the literati, and the literati on their part con demn Lao-tse, thus verifying the saying, 'Parties whose principles are different cannot take counsel together.' Li Erh taught that transformation follows, as a matter of course, though doing nothing (to bring it about), and rectification ensues in the same way from being pure and still." The Tio-Te-King.--The book for so long ascribed to Lao-tse is small in size, slightly over 5,000 characters. The condensed style, with the mystic tendencies and poetical temperament of its inspir ing genius, make its meaning extraordinarily obscure. Divided at first into two parts, it has subsequently and conveniently been subdivided into 82 chapters. The chief difficulty is to determine what we are to understand by the Tao, for Te is merely its out come, especially in man, and is rightly translated by "virtue." Julien translated Tao by "la voie." Chalmers leaves it untrans lated. "No English word," he says, "is its exact equivalent. Three terms suggest themselves—the way, reason and the word; but they are all liable to objection. Were we guided by etymology, 'the way' would come nearest the original, and in one or two passages the idea of a way seem , to be in the term ; but this is too mate rialistic to serve the purpose of a translation. 'Reason,' again, seems to be more like a quality or attribute of some conscious being than Tao is. It might even be translated by 'the Word' in the sense of Acryos." Analysis of Tio.—The character at (Tao) was, primarily, the symbol of a way, road or path ; and then, figuratively, it was used, as we also use way, in the senses of means and method—the course that we pursue in passing from one thing or concept to an other as its end or result. It is the name of a quality. Sir Robert Douglas has well said (Confucianism and Taoism, p. 189) : "If we were compelled to adopt a single word to represent the Tao of Lao-tse, we should prefer the sense in which it is used by Con fucius, 'the way,' that is, ,c4006os." What, then, was the quality which Lao-tse had in view, and which he thought of as the Tao? It was the simplicity of spon taneity, action (which might be called non-action) without motive, free from all selfish purpose, resting in nothing but its own accom plishment. This is found in the phenomena of the material world. "All things spring up without a word spoken, and grow without a claim for their production. They go through their processes with out any display of pride in them ; and the results are realized without any assumption of ownership. It is owing to the absence of such assumption that the results and their processes do not dis appear" (chap. ii.). It only needs the same quality in the arrange ments and measures of government to make society beautiful and happy. "A government conducted by sages would free the hearts of the people from inordinate desires, fill their bellies, keep their ambitions feeble and strengthen their bones. They would con stantly keep the people without knowledge and free from desires; and, where there were those who had knowledge, they would have them so that they would not dare to put it in practice" (chap. iii.). A corresponding course observed by individual man in his government of himself becoming again "as a little child" (chaps. x. and xxviii.) will have corresponding results. "His constant vir tue will be complete, and he will return to the primitive simplicity" (chap. xxviii.).