Lepidoptera

wing, moths, fig, species, scales, wings and butterflies

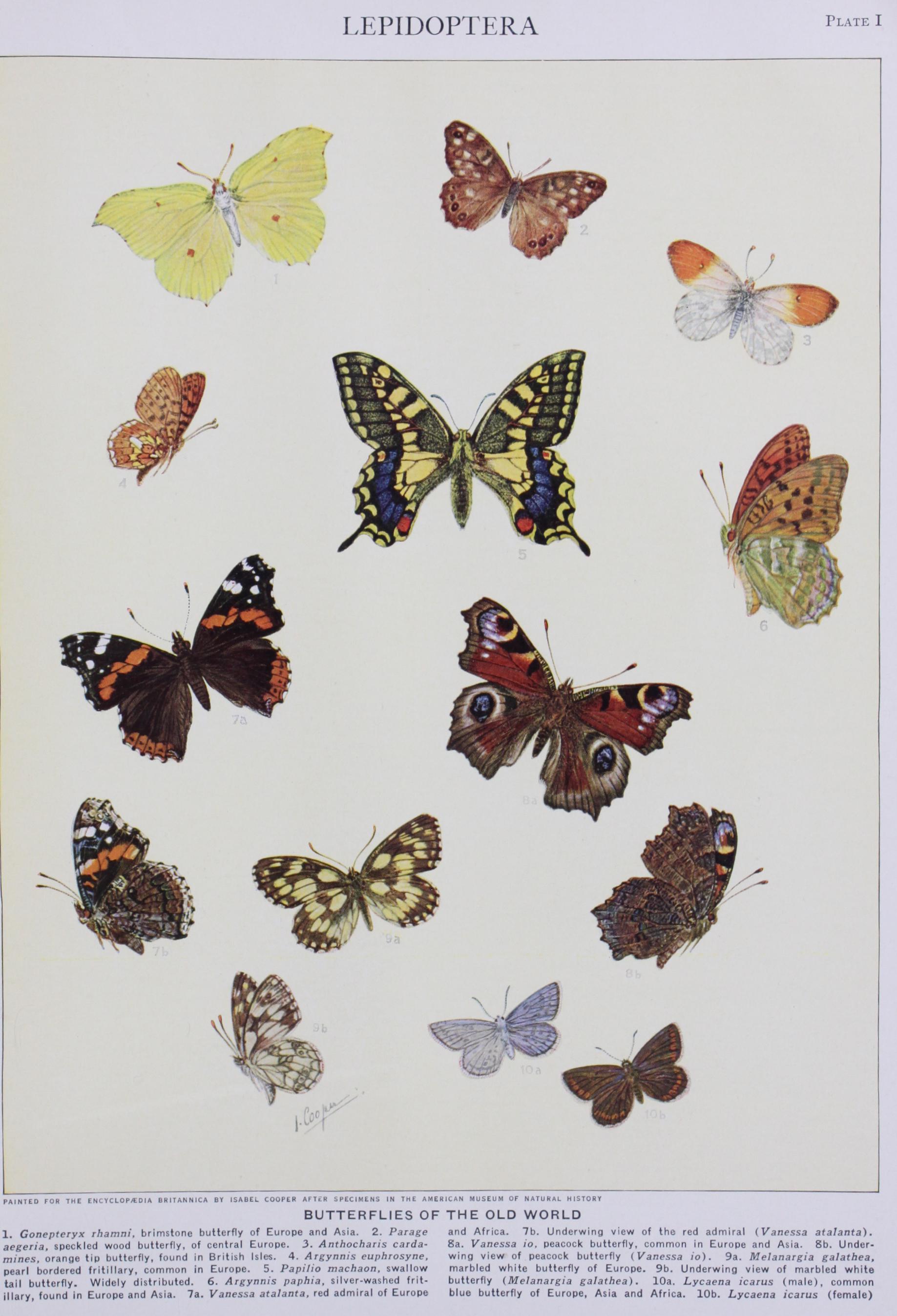

LEPIDOPTERA, the name used in zoological classification for that order of insects which comprises the butterflies and moths. The term (Gr. Xeris, a scale, and rrEp6P, a wing) was first used by Linnaeus (1735) and has been retained by all naturalists after him. Lepidoptera are among the most familiar and easily recognizable of insects and have long been popular objects for study and collecting, largely on account of the great beauty of coloration exhibited by so many of the species, together with the interest that is afforded by following their transformations. Their most easily observable characteristic is the scaly covering of the wings, body and appendages, which comes off on the fingers as a dust when these insects are handled, and, if examined under a microscope, this "dust" is seen to be composed of minute scales of definite forms. Most Lepidoptera also possess a coiled "tongue" or haustellum in front of the head. Metamorphosis is complete and the larvae are caterpillars which carry up to a maximum of eight pairs of feet; the pupae generally have their appendages more or less glued down to the body and are said to be obtected and are usually enclosed in a silken cocoon or in an earthen cell. At least 8o,000 species have been described and of these over 2,000 inhabit the British isles and more than 9,000 occur in America, north of Mexico.

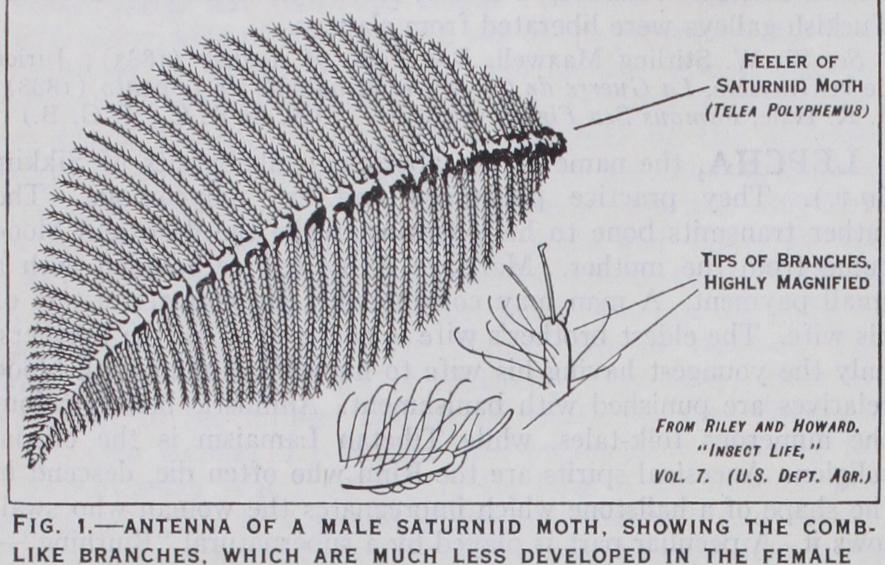

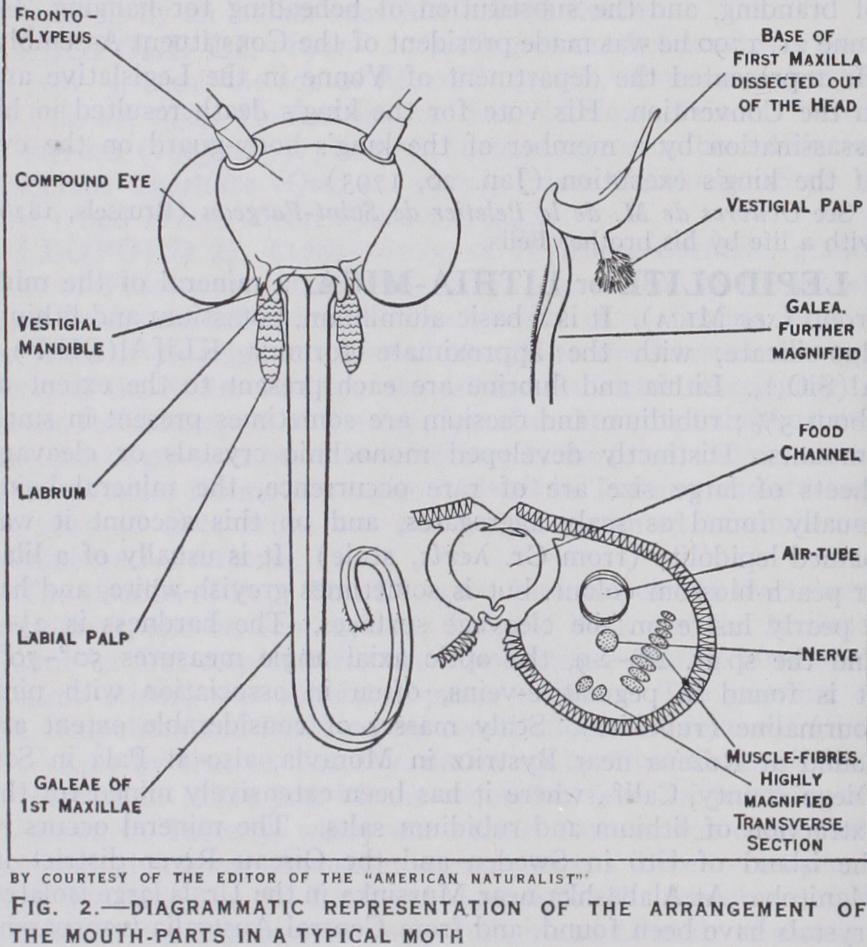

The Head.—The head is small and sub-globular in shape with the compound eyes exceedingly well developed and a pair of simple eyes or ocelli often present on the vertex (fig. 3). The antennae are many-jointed : in numerous moths they are thread like, in others they bear comb-like processes and are said to be pectinate (fig. 1), a development that is most pronounced in the males; among butterflies the antennae terminate in a club or knob. The mouth-parts (fig. 2) are nearly always adapted for sucking, with the mandibles reduced to vestiges or entirely want ing. The maxillae have their two galeae greatly elongated and interlocked to form a sucking tube, through which the food is imbibed ; it is coiled up in a watch-spring-like manner when at rest, but extended straight out when sucking nectar from flowers.

Maxillary palpi are generally re duced or wanting and the labium is represented by a small plate generally bearing prominent three-jointed palpi. In some Le pidoptera the mouth-parts are aborted and no food is taken in the adult stage, while at the other extreme in certain hawk-moths the haustellum is over 6in. long

and adapted for probing the deeply-seated nectaries of tubular flowers. In a few cases the haus tellum bears toothed spines at its apex, and those moths which possess this feature are able to lacerate the rind of fruits and suck the juices within.

The Thorax.

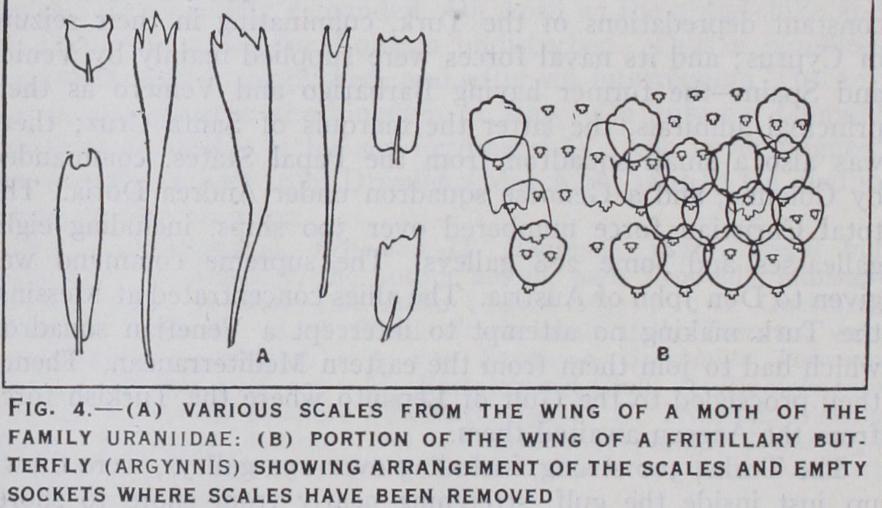

The thorax (fig. 3) has its first segment small and usually collar-like, but often bearing lateral processes or patagia that are very characteristic of the order. The mesothorax is very large and carries a pair of well-developed plates or tegulae, which often overlap the bases of the wings; in almost all species the metathorax is small and inconspicuous. The wings are mem branous and clothed with modified hairs termed scales ; in many species almost every transition between flattened hairs and broad scales can be detected under a microscope. Most scales are longi tudinally striated and there are often tiny cross strioles or con necting bars between the striae. Each scale is provided with a minute pedicel which fits into a tiny socket in the wing-membrane, and in many butterflies they are arranged in regular rows, as shown in fig. 4. Peculiar scales known as androconia are found in the wings of the males of certain Lepidoptera; in some cases they occur in "brands" or patches and physiologically they are glan dular structures that secrete an odour often very characteristic for particular species. The wings of a side are linked together by a coupling apparatus which exists in several forms (fig. 5). In the primitive swift moths a finger-like process or jugum of the fore wing grips and overlaps the base of the hind wing when the insect is in flight. In most moths a group of stiff setae, forming the frenulum, arises from the base of the hind wing and passes be neath the fore wing where it is retained in position by a catch or retinaculum; in the male the setae of the frenulum are usually fused into a single stout bristle, but in the female they remain separate. Among some moths and in butterflies there is no frenulum, and the humeral lobe at the base of the hind wing is greatly developed and projects some distance beneath the fore wing, where it is held in position.