Library Architecture

modern, books, libraries, reading, solution, public, light, paris and shelves

LIBRARY ARCHITECTURE. Architecturally, the li brary is a modern problem. There were, of course, many famous libraries before modern times, but from the description that we have of those of antiquity, and from the examples still existing of libraries of the Renaissance on to the end of the 18th century, it is clear that the great collections of books were kept simply in rooms or galleries furnished with shelves or cupboards, and some times with heavy, pulpit-like counters on which the ponderous folios could be rested. Aesthetically, the treatment of these rooms was of ten masterful, as in the Vatican, the Biblioteca Lorenziana in Florence and the old Ste. Genevieve library (now in the Lycee Henri IV.) in Paris; but it was never developed as the solution of a peculiar problem, and differed in no special way from the treatment of other equally delightful examples of domestic architecture of the time. For private libraries, or libraries open only to a selected public, such as those of clubs, scientific institutions and special departments in our modern universities, the old scheme, in which the shelves of books provide a decoration for the walls rivalling the finest tapestries, can hardly be improved. But for the requirements of the modern public library, which has to meet demands peculiar to modern conditions, the old plan cannot serve.

The modern problem first presented itself early in the 19th century, with the tremendous growth in the number of books published and the development of the democratic desire to place well-classified collections at the service of the general public. The mere extension of the type of libraries as then existed was found to be no solution. We have the record of such a scheme in the library project of Boulee (1729-99), entitled Memoir on the Means to Secure for the King's Library the Advantages Required for this Monument (1785). This memoir is accompanied by a drawing showing a gigantic gallery covered by a barrel vault, supported on two colonnades which vanish in the distance at a terminal apse, and admitting the light only through a rectangular opening in the centre. Under the colonnades there are three plat forms, each supporting a tier of books. Aesthetically, the design is not without merit in its severity, and it shows, moreover, an appreciation of the magnitude of the new problem. But the solution was not to be found in a mere increase in size ; rather in a frank segregation of the public in reading rooms and of the creation of separate store-rooms for the books. These store rooms are what we now call the "stacks," where in general the public is not admitted and an intensive use of space can be made.

As early as 1835, the French architect, Benjamin Delessert, suggested for the proposed Bibliotheque Nationale in Paris, a cir cular reading room, with the book-stacks surrounding it, lying radially to the centre. The old Wolfenbuttel library (1706), and

its derivative, the Radcliffe library at Oxford, had already been built on a circular plan, but without the separate book-stacks. This circular reading room recommended itself by allowing the librarian (installed on a raised platform in the centre) an easier supervision of the readers. Delessert's plan probably suggested that of the reading room of the British Museum (R. and S. Smirke, architects, 1852) where, however, the stacks are rather awkwardly arranged around the central dome.

When Henri Labrouste was appointed architect for the new Ste. Genevieve library in Paris (1843) the site selected, being long and narrow, almost forced the solution of a reading room occupying the entire upper floor of the building and containing many of the books, as in the old libraries, but with other spaces for books beneath,—a scheme that in recent years has been used in many important libraries. Although the shape of the lot unfortunately made it necessary to divide the book storage into two sections, Labrouste had, nevertheless, evolved a masterly solution of his problem, a solution so modern in his frank treatment of structural elements that this building remains one of the prototypes of modern architecture.

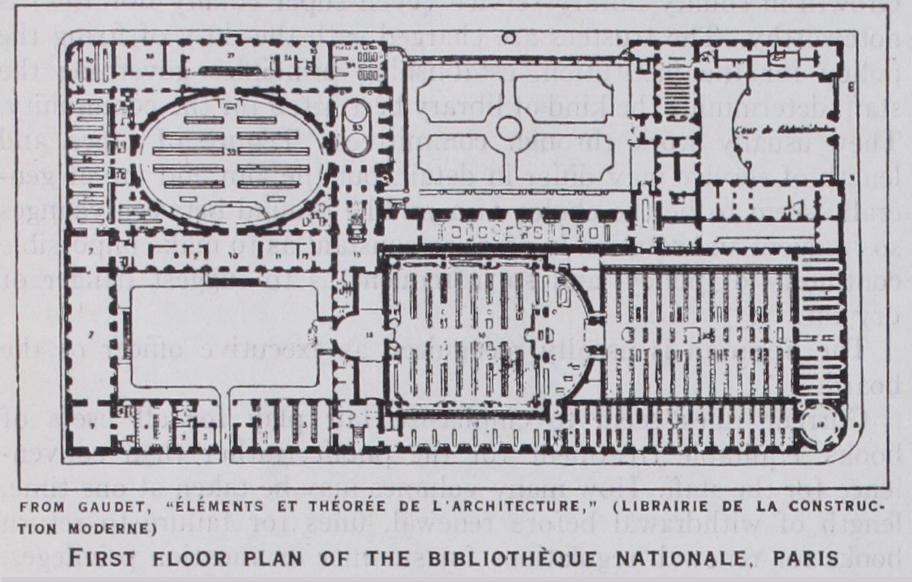

Later, in the plans for the Bibliotheque Nationale in Paris (1854), where he was less hampered by the exigencies of space, Labrouste gave another remarkable building. The main reading room is square, with an apse, where the librarians are installed, facing its entrance and commanding that to the stacks. The read ing room is surrounded by three tiers of shelves, with the light coming through a large opening on the north side, and from nine domes which each rest on four light steel columns. The atmos phere of the rooms is quiet and restful and the light is excellent. The most remarkable part of the composition, however, is the book-stack (magasin des imprimes), a huge room, 90 ft. by 120 feet. Here the principle of the modern book-stack is first evolved. The shell of masonry is covered by a glass skylight, which allows daylight to penetrate every corner, while inside this shell, the metal framework of the book tiers and the passages between is an entirely independent construction resting on the basement floor. These are the essentials of the modern book-stack, the invention of which has been attributed quite incorrectly to W. H. Ware and Bernard Green; the only improvement contributed by these gentlemen, many years later, was the closer packing of the shelves and the elimination of such woodwork as remained.