Lighting Practice Outside the Home

light, feet, units, lamp, usually, highway, seeing, system, surface and lamps

LIGHTING PRACTICE OUTSIDE THE HOME In medicine, manufacturing, agriculture, crime detection, as tronomy, and many other processes associated with life or learn ing, light or at least the near visible radiations, becomes useful in other ways than for seeing. The sterilizing and bactericidal prop erties of carefully selected qualities of light have been growing rapidly in importance since about 193o. Through the property of fluorescence by which many specimens of various materials can be analyzed, compared or made to disclose obscure internal changes the work of crime detection and prevention is greatly advanced. Other types of "light" are used to bleach oils, coagulate gums; automatically grade, sort, and count various coloured manu factured articles; detect smoke and atmospheric impurities; cre ate vitamins in foods; cure plant diseases,—a list running to a surprisingly greater length as man becomes more adept in gener ating radiant energy of the different wave lengths. However, in merely the realm of human seeing there are several different classes of applied lighting among which the following are typical in illustrating the major principles.

Factories and Industrials.

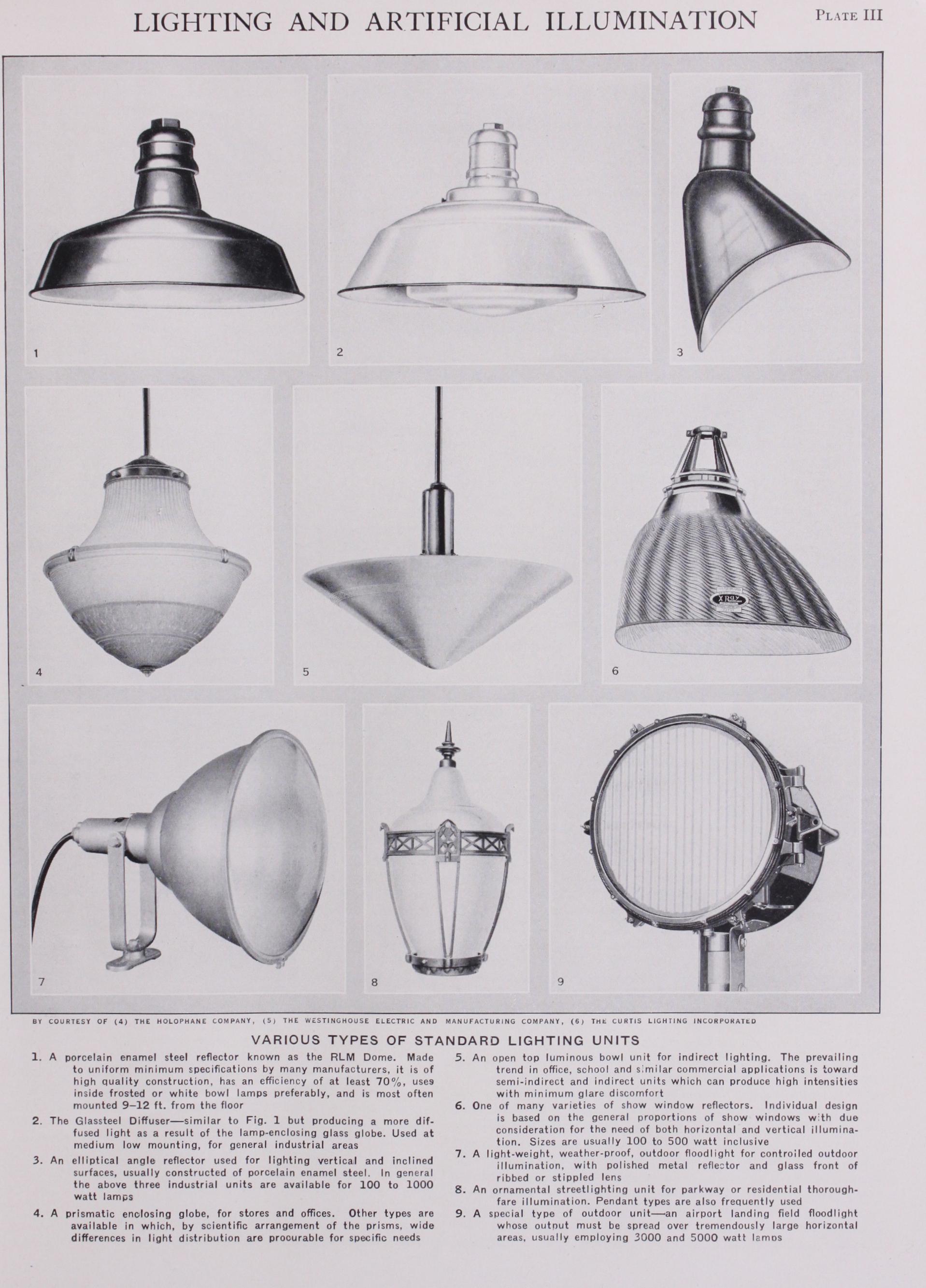

The general inadequacy of natu ral light for seeing tasks removed more than some 20 feet from adequate window areas, and the changeability of daylight, has brought about the common practice of lighting the factory to a general average of 5 to 25 foot-candles, over all the floor areas of importance. This is usually accomplished by porcelain enameled steel, silvered glass, or prismatic glass direct reflectors spaced symmetrically over the ceiling surface with the distance between units approximately equal to the height above the floor. Up to perhaps 1930 it was customary to employ the RLM style of metal reflector with the 20o watt white bowl incandescent lamp equalling some 2 watts per square foot of floor area or equivalent to approximately i o foot-candles on the horizontal work planes. For factory ceilings much above 14 feet and certainly in the high bays of assembly plants, it is common practice to suspend units of the 500, 75o or i000 watt sizes in rather narrow-beam types of opaque reflectors, supplemented with angle type units at much lower positions. Where an important machine or group of ma chinery is situated there should be provision for a localized gen eral lighting arrangement, typified by ceiling units concentrating strong beams over small areas and by carefully shaded local lights built into the machines themselves. In the lighting of stair and passage-ways and to insure reasonable safety for all workmen, there should be a dual circuit providing for automatic usage of a storage battery electrical supply in the event of other failures. The I.E.S. Code of lighting for factories, etc., revised in 1932 and written into the laws of many States, provides the more de tailed recommendations for architects, builders and operators.

In the United States industrial lighting is about evenly divided between 110-115 volts and 120-125 volts. In western Europe the 2 20 volt range is general which has the advantage of less expense and losses in wiring but a lower efficiency of lamp and a somewhat increased hazard.

In the metal working and automobile industries it is usually of more importance to see objects clearly and to provide intensi ties on the order of 25 foot-candles or better than it is to deter mine an exact colour ; consequently in the United States about 1934 there began to be used an increasing number of the 400 watt size of high intensity mercury vapour lamps mounted some 15 to 5o feet above the work and equipped with aluminium or concen trating type glass reflectors.

Streetlighting.

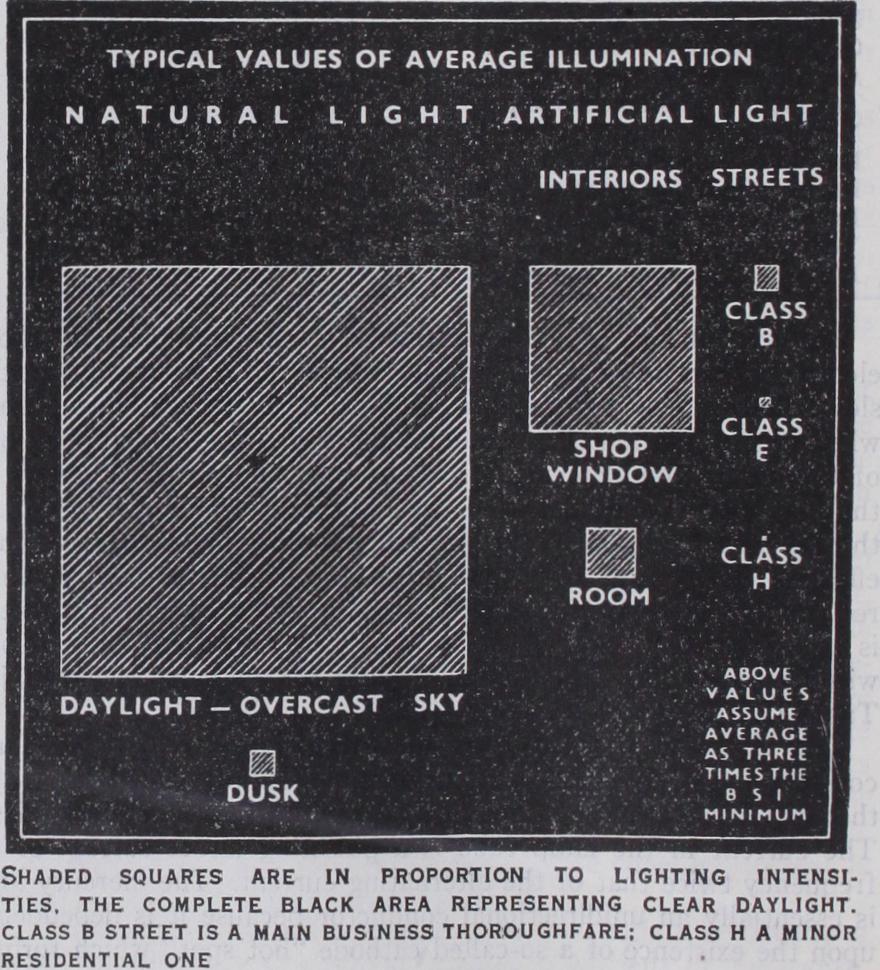

The chief criterion of good streetlighting is based upon safety and upon seeing an object chiefly by silhouette at a distance within which the high speed vehicle may safely stop. The intensity of illumination on the horizontal road surface is usually of secondary importance and may range from 2 or 3 foot candles in the case of a brilliantly lighted business street, to even less than 0.1 foot-candle or five times full moonlight. When light ing a heavy traffic thoroughfare usually carrying more than 1500 vehicles per hour in both directions, it is good practice to place lighting standards or units in opposite arrangement and preferably extending out beyond the curb line at a mounting height of not less than 18 feet. Good practice dictates a spacing not greater than 150 feet and each individual lamp producing not less than 10,000 lumens. This would be a size roughly equivalent to r 000 candle-power or 400 watts. Where trees do not interfere, the pre ferred height is between 20 and 3o feet. Practice for illuminating rural highways will vary considerably but in general is on the order of 20 units to the mile and with a lamp size from 6000 to 10,000 lumens. The unit should be mounted as nearly over the centre line of the highway as possible, or else staggered on both sides and in order to eliminate glare and permit reasonably good distribution between units these should be mounted some 3o feet or more high. The series system using a constant current but a voltage that varies in accordance with the number of lamps per circuit, is common. In England, about 1933, the 400 watt high intensity mercury lamp began to be employed successfully for streetlighting. About the same time in the United States the sodium vapour lamp was successfully used in limited installations. The proper installation of a good highway lighting system may represent investment charges from $3000 to $5000 per mile, and maintenance charges on the order of $5oo to $r000 per mile annually. Where the entire system, including poles and distribu tion circuits, is installed and used solely for highway lighting purposes, the annual costs in the United States in 1934 including energy and depreciation, usually ranged from $1500 to $2000. In western Europe some highway installations using catenary cable suspensions for sodium vapour lamps, are operating at some what higher costs. In metropolitan centres the ornamental post equipment consists of cast-iron, rolled sheet steel or hollow spun concrete standards fed from underground cables to large wattage filament lamps in diffusing ornamental globes at the top. With such equipment the facades of buildings act as fair reflectors and no attempt is made to control accurately the direction of light. Where spacings become greater as in residential streets, the prismatic refractor reduces the light escaping crosswise of the roadway and increases it manyf old longitudinally. This asym metric distribution is designed for maximum candle-power at an angle of about 75° with practically no light in the upper hemi sphere. By reason of both diffuse and specular reflection from the road surface, this becomes a lighter background against which darker objects are visible. Consequently, much of the success of a street or highway lighting system depends upon surface colour ing and texture. For visibility reasons a light coloured concrete, brick, or gravel is much preferable to the dark surfaces.