Types of Lights

light, flashes, apparatus, divergence, intervals, flash, duration, fixed and focal

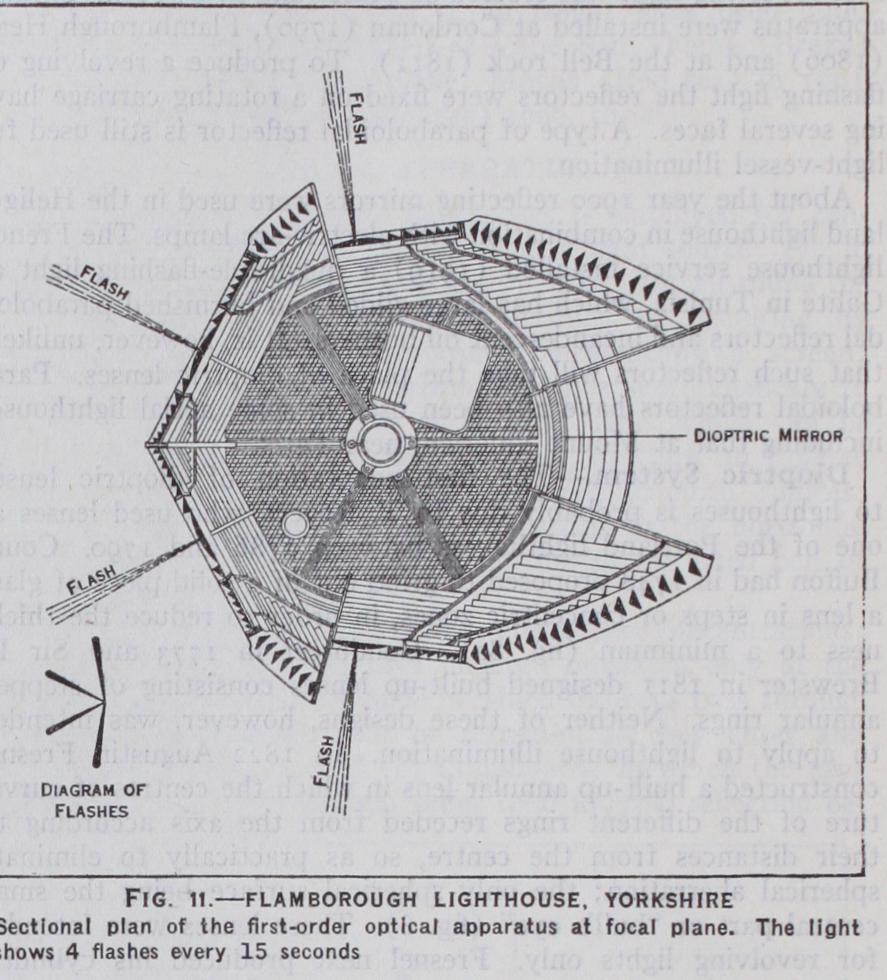

Group-flashing Lights.—One of the most useful distinctions consists in the grouping of two or more flashes separated by short intervals of darkness, the group being succeeded by a longer flashing). A modification of the system consists in grouping two or more lenses together and filling the remaining angle in azimuth by a reinforcing mirror. A sectional plan of the quadruple-flashing first-order apparatus at Flamborough, Yorkshire, is shown in fig. 11 on page 92.

Hyper-radial Apparatus.—In 1885 Messrs. Barbier of Paris constructed the first hyper-radial apparatus (1,330 mm. focal dis tance) to the design of D. and C. Stevenson. Apparatus of similar focal distance were subsequently established at a number of other lighthouses. That at Manora Point, Karachi, India (1908) is illustrated in fig. The introduction of incandescent oil burners and electric lamps of focal compactness and high intrinsic bright ness has rendered unnecessary the provision of optics of such large dimensions.

Fixed and Flashing Lights.—The use of these lights, which show a fixed beam varied at intervals by more powerful flashes, is undesirable, though a large number were constructed in the earlier years of dioptric illumination and some are still in exis tence. In certain conditions of the atmosphere it is possible for the fixed-light of low power to be entirely obscured while the flashes are visible, thus the true characteristic of the light is vitiated.

Screens and Cuts.—Screens of coloured glass, intended to distinguish the light in particular azimuths, and of sheet iron, when it is desired to "cut off" the light sharply on any angle, should be fixed as far from the centre of the light as possible, in order to reduce commingling, in the first case, and the escape, in the second case, of the light rays due to divergence. These screens are usually attached to the lantern framing.

Divergence.—A dioptric apparatus designed to bend all inci dent rays of light from the light source in a horizontal direction would, if the flame could be a point, have the effect of projecting a band or zone of light (in the case of a fixed apparatus) and a cylinder of light rays (in the case of a flashing light) towards the horizon. Under such conditions the mariner in the near dis tance would receive no light as the rays would pass above the level of his eye and be visible only on the horizon. In practice this does not occur, sufficient natural divergence being produced ordinarily owing to the magnitude of the flame. When the electric arc or an incandescent electric-lamp of small focal diameter is employed it is sometimes necessary to design the prisms so as to produce artificial divergence. The measure of the natural hori zontal divergence for any point of the lens is twice the angle whose tangent is the ratio of the radius of the illuminating source to the distance of the point from the geometrical centre of the lens and for calculating the vertical divergence the vertical dimen sions of the light source, above and below the focal plane, must in turn be substituted for the radius, and the sum of the angles thus obtained is the total divergence. In fixed dioptric-lights there

is, of course, no divergence in the horizontal plane. In revolving lights the horizontal divergence is a matter of considerable im portance, determining as it does the duration of flash, i.e., the length of time the flash is visible to the mariner.