A Carpenters Bench

fig, jaw, vise, cut, top, mortise, leg and piece

After the top has been nailed, take a straight edge and mark lines across each end to indicate where the ends of these top boards are to be sawed off. They should be of the same length as the sides (Fig. 116).

The vise may be made next. There are various ways of making this very important part of the bench. The kind which seems to be most commonly used by carpenters nowadays—aside from the rapid-acting vise—is the one shown in Fig. 116.

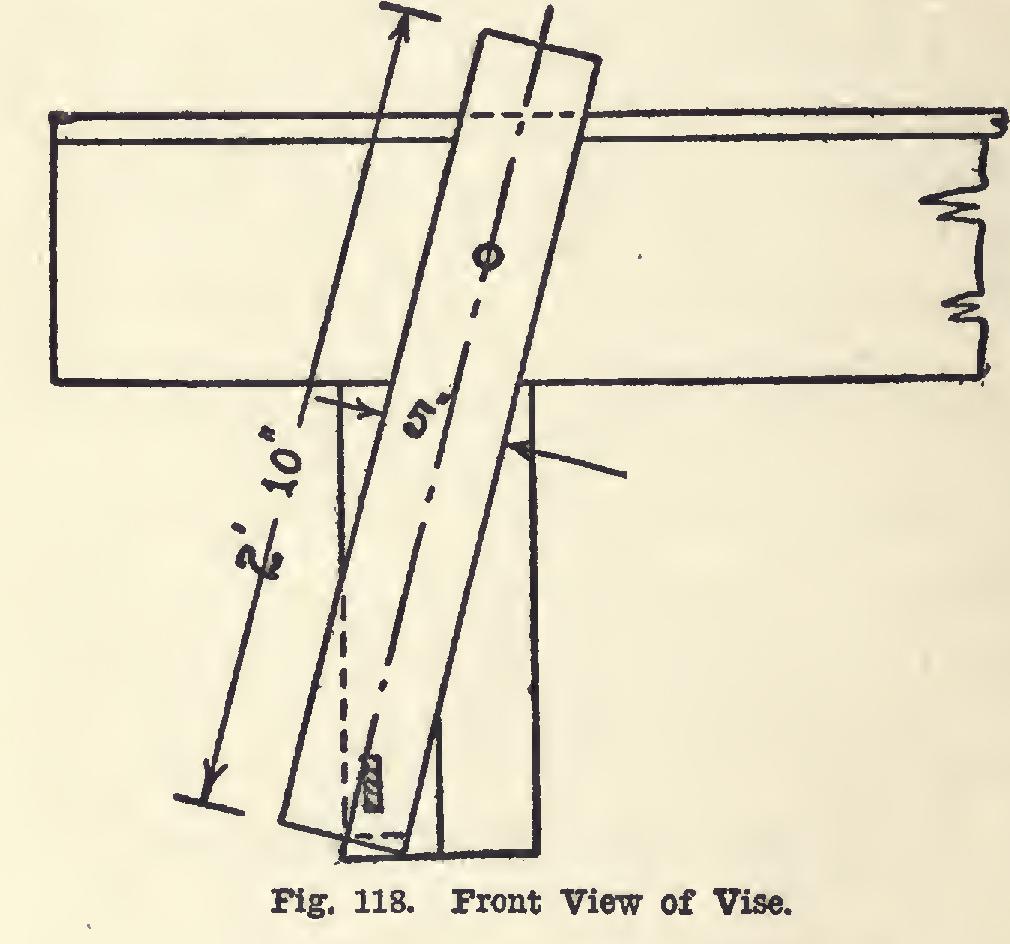

In Fig. 118 is shown a vise in which the movable jaw is inclined somewhat toward the worker. There is an advantage in this kind of vise, in that vertical pieces can be held without exerting any side strain—or at most very little —upon the vise. This position of the jaw also holds the work farther away from the bench's end, which is often of advantage. With this placing of the vise jaw, a "two by six" is used for the bench leg, or two pieces of "two by four" may be cleated together.

To make the inclined vise, take the piece of one and one-half-inch oak, and joint its edges so that it shall have a width of five inches. Draw a center line (Fig. 118). Hold the piece against the bench in the position indicated in Fig. 118, and mark the location of the large hole for the vise screw. This hole should be bored in both bench and vise jaw. Its size will be governed by the size of the screw. The hole should be a little larger. In Fig. 118 the hole is bored in the middle of the ten-inch board, and in the middle of the second "two by four" leg.

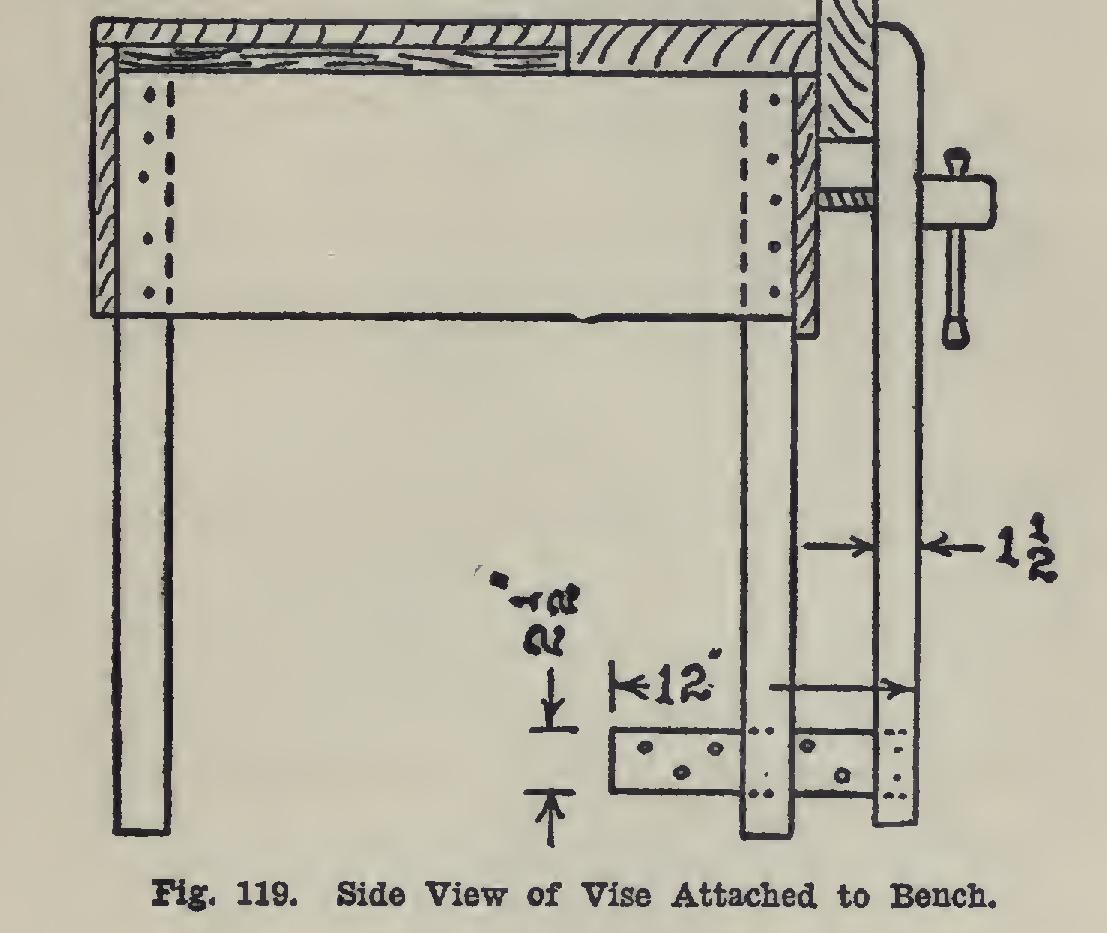

Insert the screw into the hole in the jaw, and screw the face-plate fast. Put the jaw in place against the bench, and mark as indicated by the dotted lines (Fig. 118), saw and plane to this shape, rounding the top end as in Fig. 119.

The value of the grip of any vise depends upon its jaws being parallel. In Fig. 119 is shown the manner of adjusting this kind of vise to meet this requirement. The small piece with the holes in it slides in and out through a mortise in the leg. A dowel-pin or a bolt (Fig. 116) is passed through one of these holes, and holds the jaw as desired.

Plane up the seven-eighths by two and one half by twelve-inch piece, and bore one-half-inch holes as indicated in Fig. 119.

With try-square and gauge, lay out a mortise in the jaw (Fig. 118), and cut it. Lay out and cut a corresponding mortise in the leg. The mortise in the leg should be cut slightly larger than the piece which enters it, so that it may not bind.

Fit the piece with the half-inch holes into the mortise of the movable jaw. With the steel square, hold its edge square to the face of the jaw, and fasten the two together, using dowels, screws, or nails through the edge of the jaw.

Set and fasten to the inside of the bench leg the "nut" for the vise screw, and the vise is ready for use.

The vise shown in Fig. 116 is somewhat easier to make. The hole for the screw is to be bored so that it will pass through the middle of the single "two by four" leg. The mortise for the seven-eighths by two and one-half-inch piece with the holes in it, is to be cut directly below this hole—that is, in the middle of the leg. It would better be laid out and cut, however, after the corresponding mortise has been cut in the movable jaw.

Square up the stock for the jaw to the width desired, with a length less by an inch or two than the height of the bench. This is to keep the end of the jaw off the floor. The top should be rounded, and the sides sloped from a point nine or ten inches below the top, so that the width at the bottom will be about three or four inches. Before putting the slope on the joint edge, lay off the mortise at the bottom, and the screw-hole at the top.

For holding long boards, bore a series of three-quarters or seven-eighths-inch holes as indicated in Fig. 116. Make a wooden peg that can . be forced into these holes. Whittle it so that it will wedge slightly, and cut it out so that it may have a "lip" to keep springy boards up against the bench (Fig. 116).

For a bench-stop, there are various devices in common use. Iron bench-stops can be pur chased. A couple of nails or screws put into the bench top are often used for holding thin stock. Sometimes mortises are cut, and one inch square hardwood plugs are snugly fitted. If this is done on a bench with a thin board top, such as this one is, a heavy block should be fastened to the under side, else the mortise would soon lose its shape and the pin would fall through. Such mortises are usually cut slightly inclined at the top, toward the worker. A block with a cut in one end does quite well, but is likely to injure the ends of soft wood (Fig. 116).

Fig. 119 shows a bench in which the top has been made more substantial by the placing of a heavy plank on the working side. That there might be no offset, the two lighter boards were raised to a level by the placing of thin pieces upon the cross-pieces. Care should be taken in the selection of a plank for this purpose, to get one that will keep its shape.

The dimensions given are, of course, merely suggestive. The bench might be made longer, more cross-pieces in that case being added; or it might be made shorter. The height given is about the average. A tall man would probably want it a little higher; a boy or short man, lower.