Architectural Framing

hole, pins and piece

Draw-Bored Framing.

This type of framing is very useful in some of the oblique joints in open-timbered roofs, which are so much in favor again to-day. In imitation of the pins seen in some of the fine old open-timbered roofs of the Middle Ages, some architects like all joints in modern roofs of that class to be pinned with stout wooden pins left standing out a little from the surface. The writer recently saw a fine church roof carried out with this detail, and draw-boring was used throughout with excellent results.

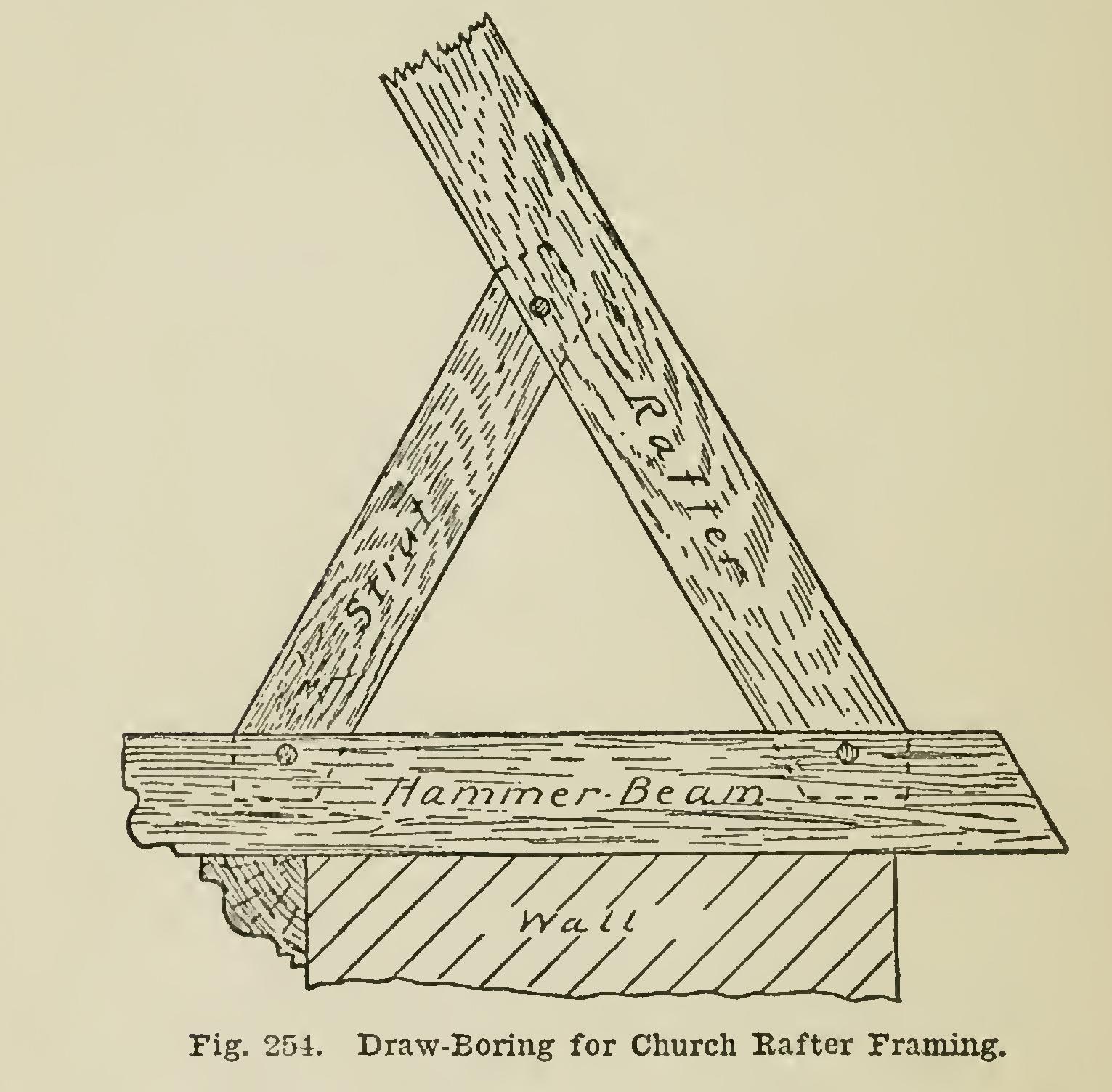

Fig. 254 shows the foot of the rafter resting on a short "hammer-beam" on the wall, with an inclined brace or strut framed in the angle.

It was practically impossible to clamp up such a piece of framing; but, by draw-boring for the pins, the three oblique shoulders were easily bropght tight. and a good job made of it with out much trouble.

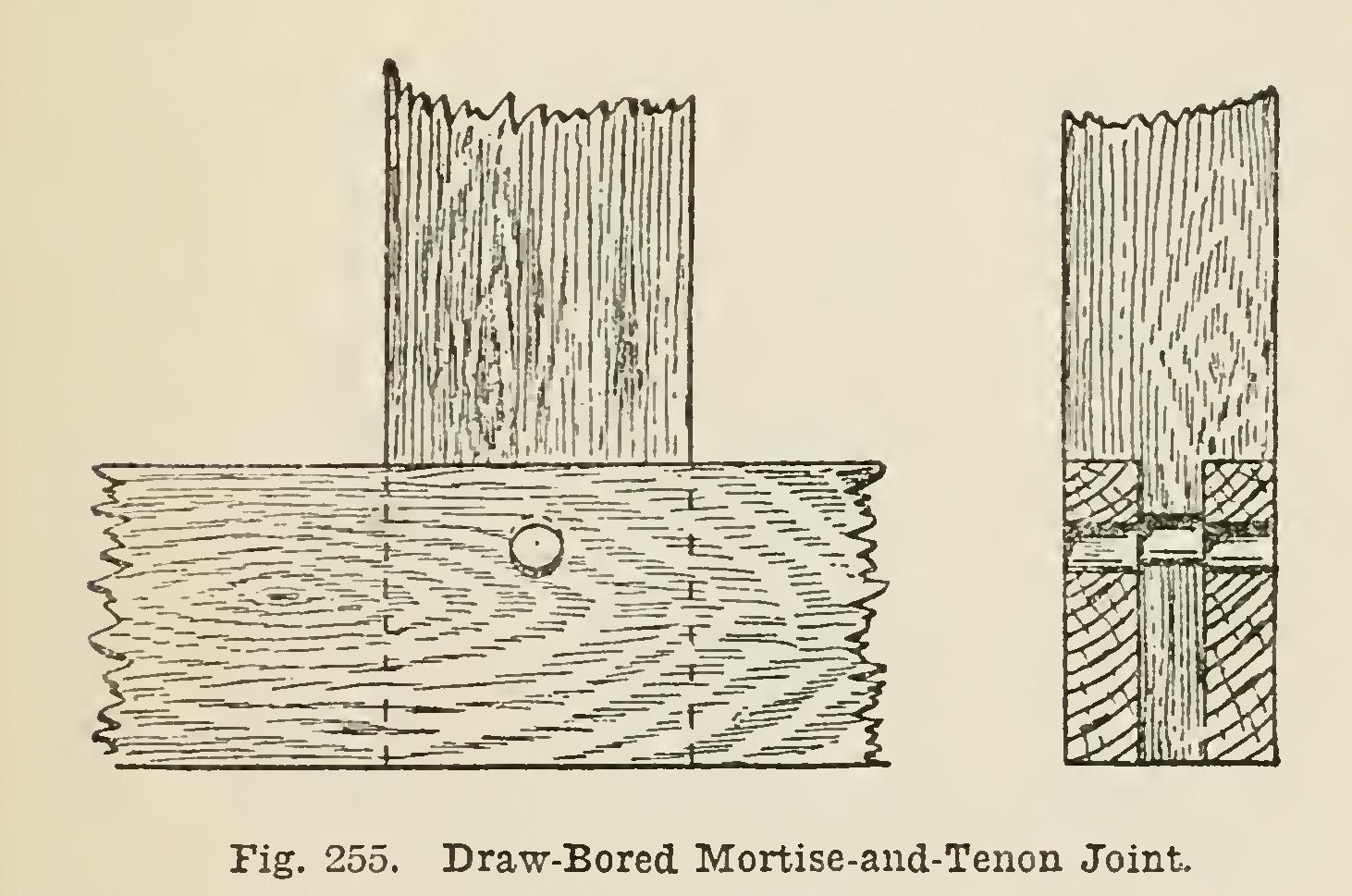

The method of draw-boring for pins in framing is a very old one—much used in Eng land—and is well illustrated in Fig. 255, which shows an elevation and a sectional view through a common mortise-and-tenon joint, with the holes for the pin "draw-bored." It will be seen

that instead of the usual method of pinning— namely, to clamp the shoulders tight up, and bore a hole right through the mortised piece and the tenon at one operation, and then to insert a wooden pin—another method is adopted.

First, a hole is bored through the mortised piece before the tenon is inserted. The tenon is then entered and driven home, and the position of the hole marked on it. The tenon is then with drawn, and a hole bored in it a trifle nearer the shoulder than the hole in the mortised piece. The joint is then glued (or painted, if for out door work) and put together, after which a pin well tapered at the point is driven into the hole through the framing. The effect is, of course, to force the shoulders up very tight, making a joint that will effectively resist ordinary shrinkage or, any changes affecting the ordinary joint. It is usual, and also advisable, in draw-boring, to drive a steel pin through the hole before insert ing the wooden pin.