Steel 13

carbon, gas, furnace, air, charge, metal and required

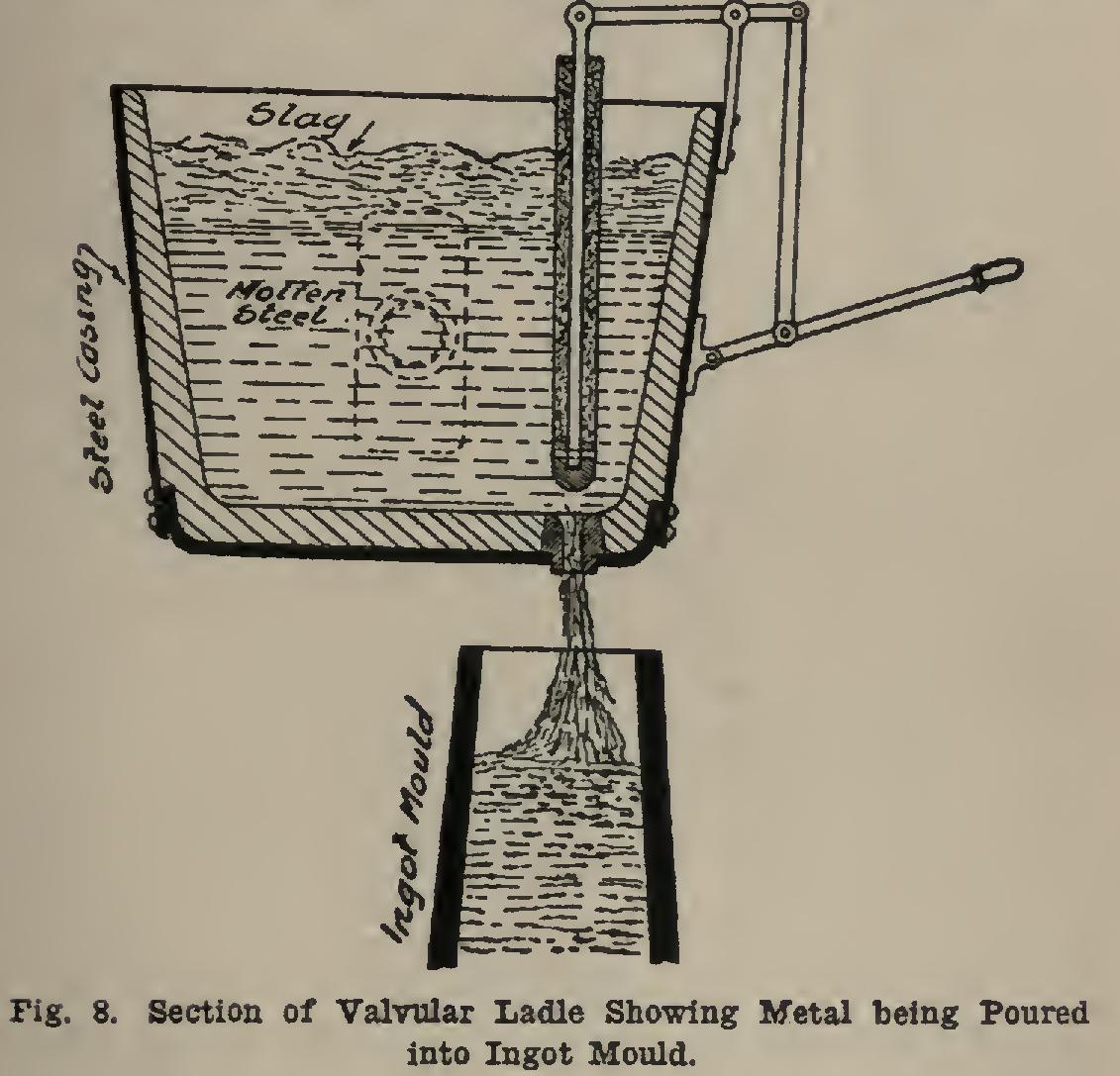

The material is now poured into a ladle, and from that into ingot moulds. For a description of ingots, see Article 16.

Bessemer steel is not so homogeneous nor so reliable as crucible or open-hearth steel (see next article), on account of the fact that in replacing the carbon which has been burned out, it must be done by a small charge, and there is therefore the liability that the carbon will not be uniformly distributed throughout the mass of ten or twelve tons. Bessemer steel is therefore not specified for use in bridges, buildings, and structures in general; but for rails, farm machinery, wire, and nails, it is in general use.

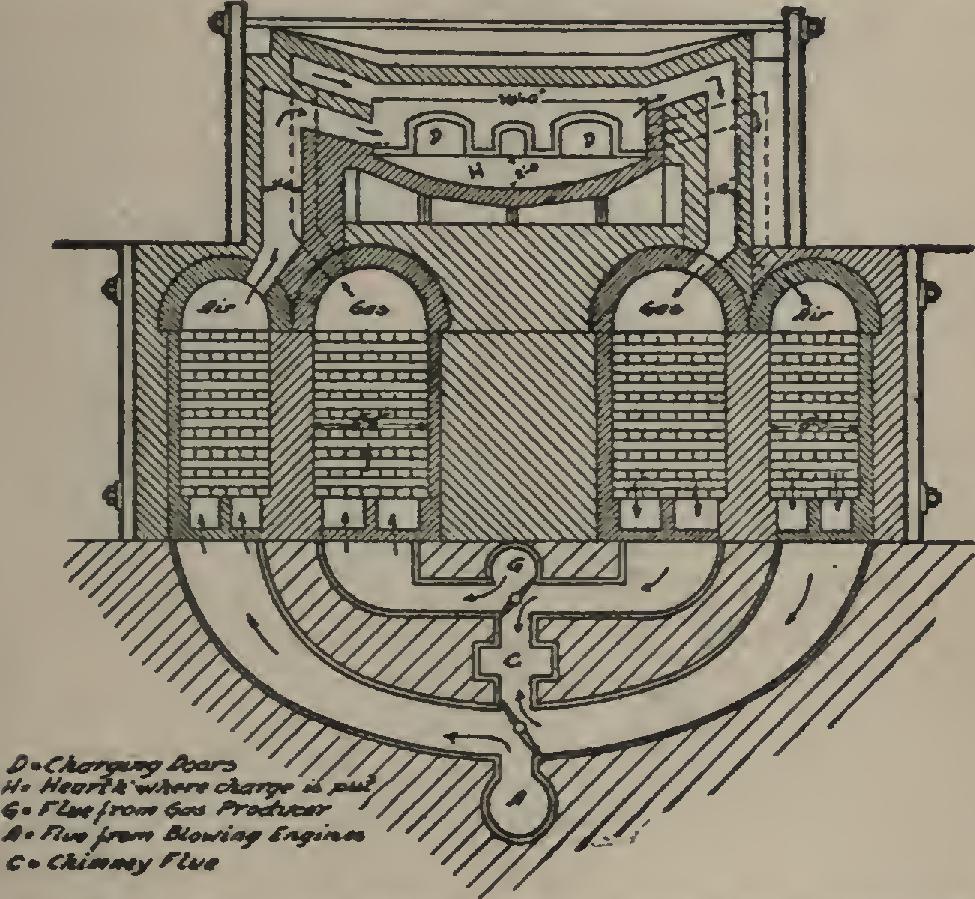

Fig. 7. Section of Open-Hearth Furnace, with Regenerative Fur nace, and Diagram of Air and Gas Valves.

15. Open-Hearth Steel. In this case the furnace used is as shown in Fig. 7. The depth of molten metal should be 18 to 24 inches in a furnace of from 30 to 50 tons capacity. The charge consists either of cast iron (melted in some cases) or of cast iron and scrap. The stock must be low in phosphorus and sulphur, or the steel will not be of use, and also the lining of the furnace will be destroyed by the phosphorus attacking it. But, in case low phosphorus and sulphur ores are not available, the furnace may be lined with lime, magnesite, dolomite, or some other like material, and a quantity of limestone or limestone and ore added to the charge. In this latter case, the phosphorus will not ruin the lining, and it will be taken from the metal by the lime and ore and transferred to the slag. The sulphur will be eliminated in part by burn ing out; and most of the remainder combines with certain materials which are added during the heat, and is carried off in the slag.

The charge is melted by the burning of either natural or artificial gas (producer gas) and air forced in under pressure. These enter the fur nace on opposite sides of the hearth, join, burn, and beat down on the charge, thus melting it and keeping it melted.

The waste gases then pass out and through a brick checkerwork similar to that in the hot blast stoves, and then up the stack. When the checkerwork is hot in a pair of these chambers, the valves are reversed; and the gas and air, before burning in the furnace, are heated by being forced through these chambers, the burn ing gases from the furnace in the meanwhile passing through the checkerwork in the cham bers through which the gas and air first were forced. When one set of chambers becomes

cooled, the gas and air are forced through the other, and in this manner the gas and air are heated by one set of chambers while the other set is being heated by the waste gases. And so the operation goes on. Every little while, test bars are made from metal taken out of the bath, and tests made to determine the amount of car bon present. When the carbon has reached the percentage desired for the finished product, the recarburizer is added. In this case the addition of the "recarburizer" is not, as in the case of the Bessemer process, to increase the carbon, but to remove impurities.

From four to ten hours are required to run a charge. The time depends upon the amount of carbon to be burnt out. The mixture of scrap and ore with cast iron is usually so proportioned that the bath has from 0.75 to 1.00 per cent of carbon at the start. If a 0.43 per cent carbon steel is required, it will take less time to run the heat than if a 0.23 per cent carbon is required. When the metal is ready, it is run into ladles and poured into the ingot moulds.

It is evident that open-hearth steel is more homogeneous than Bessemer, since the blast can be stopped when the carbon has been burnt down to the required percentage. The mixing has been done by nature, and is therefore evenly done. In the Bessemer process, nearly all car bon is first burnt out, and then enough added to bring the carbon content up to the required per centage.

16. The Ingot. In order to prevent the slag from getting into the ingot, the metal is poured from a valvular ladle, Fig. 8. The ingots may be almost any size. The ordinary size for rails is about 63 inches high and 14 inches square, weighing about 2,000 pounds; but from this size the ingots run up to 24 by 26 inches and 5 tons in weight, or even larger, as the case demands (see Fig. 9).