Testing of Structural Steel 23

safety, factor, stress, strength, test, ultimate, structure and length

25. Factor of Safety. Now that the subject of ultimate strength and elastic limit are under stood, the subject of the "factor of safety" should be taken up. Since the strength of a structure is no greater than that of its weakest part, and since, even with the best of care in the manufacture of steel, some that is not nearly so strong as the remainder will find its way into structures, and also since at times structures will be loaded far beyond those loads for which they were designed, and the loss of life and money caused by the collapse of a structure is likely to be very great, it is therefore customary not to take any chances of having a collapse, but to make the structure much stronger than it really would need to be if the quality of the steel were known to be the same throughout. The next question is, how many times too strong shall it be? Is it 2, 3, 4, or 5, or even 6? It is seldom 2, often 3, 4, and 5, and sometimes 6. In these figures we have what is called—but inadvisedly, as will soon be seen—the factor of safety.

The stress which is used in designing mem bers is called the allowable working stress, or simply the allowable stress, and is obtained by dividing the ultimate stress by the factor of safety. The word unit-stress is understood in both cases as the stress in a certain area taken as a unit—a certain number of pounds per square inch.

If the stress which comes upon a member is Factors of Safety and Allowable Stresses Ultimate Strength of Medium Steel, 60,000 Pounds per Square Inch caused by a constant load—such as the dead weight of the structure, or a concentrated load which remains the same—then the factor of safety is small, because the conditions are quite well known. If the structure is subjected to moving loads which cause considerable jarring, then the factor of safety must be greater than in the former case. If the jarring is violent, then the factor of safety must be high. Table V gives factors of safety and allowable unit stresses for various classes of structures.

It should be noted that the ultimate strength is divided by the factor of safety to get the working stress. This should not be. The elastic limit should be divided by the factor of safety, and our so-called "factors of safety" would then be about one-half of what they now are, since the elastic limit in structural steel is one half or a little over one-half of the ultimate strength. Since, when the metal has been stressed beyond the elastic limit, the member has started to fail, and there is not much of the so-called "safety" in it, it will be clear that when a factor of safety of 4 is used, it does not signify, as it was once thought to do, that the structure is four times as safe as it would be required to be if it were certain that the steel was the same throughout, but it really means that it is only twice as safe.

This point has been called to the attention of engineers time and time again; but while they recognize the meaningless character of the pres ent so-called "factor," it has been found hard to change it, on account of the permanency which custom has imparted to it.

26. Physical Requirements. The physical requirements for soft mediums and rivet steel according to the common practice of to-day, are given in Table VI; and. tests of structural steels are given in Table VII. It will be noticed that the reduction of area is not a requirement in Table VI. This is due to the fact that the per centage of elongation indicates the same thing.

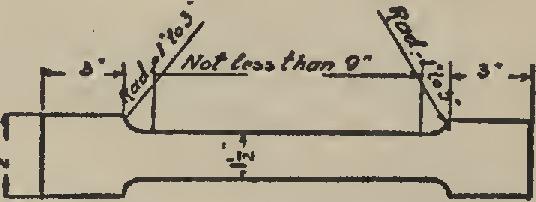

27. The Test Piece. Since probably from 75 to 85 per cent of the total elongation is within the limits of the necking-down part of the bar, and since this portion of the elongation is con stant for bars of the same diameter or rectangu lar cross-section, it is of prime importance that the length of the test piece over which the elon Fig. 22. Form and Dimensions of Steel Plate for Testing.

gation is measured be stated, and, moreover, that the length should be standard in order that different tests may be directly comparable as regards percentage of elongation shown.

Experience has shown that a length of eight inches is convenient, and this length is now most generally used. The relation of the length to the diameter of the test piece, or, if it be of square or rectangular shape, to the dimensions of the cross-section, affects the reduction of area. The ultimate strength and the elastic limit are also affected by both the area and the dimen sions of the cross-sections. Hence it is impor tant that test pieces should be standard. As yet, however, no one shape has been universally adopted, although commissions and technical societies of France, Germany, and America have each proposed as standards test pieces whose dimensions differ very little among themselves.

Where nothing is said to the contrary, struc tural steel is tested with a measured length of eight inches, and the shape of the test piece is nearly always that recommended by the Ameri can Society for Testing Materials. This is the result of the best thought and experience of the foremost steel men of this country, and, as such, should be used in all cases.