Historical and Descriptive

square, edge, scale, tongue, blade, inches and inch

The lines and figures formed on the squares of different make, sometimes vary, both as to their position on the square, and their mode of application, but a thorough understanding of the application of the scales and lines shown on any first-class tool, will enable the student to com prehend the use of the lines and figures exhibited on other first-class squares.

To insure good results, it is necessary to be careful in the selection of the tool.

The blade of the square should be 24 inches long, and two inches wide, and the tongue from 14 to 18 inches long and 1i inches wide. The tongue should be exactly at right angles with the blade, or in other words the "square" should be perfectly square.

How to Test the Square.—To test this question, get a board, about 12 or 14 inches wide, and four feet long, dress it on one side, and true up one edge as near straight as it is possible to make it. Lay the board on the bench, with the dressed side up, and the trued edge toward you, then apply the square, with the blade to the left, and mark across the prepared board with a pen knife blade, pressing close up to the edge of the tongue, and then reverse the square, and move it until the tongue is close up to the knife mark; if you find that the edge of the tongue and the mark coincide, it is a proof that the tool is cor rect enough for your purposes.

This, of course, relates to the inside edge of the blade, and the outside edge of the tongue. If these edges should not be straight or should not prove perfectly true, they should be filed or ground until they are straight or true. The outside edge of the blade should also be "trued" up to make it exactly parallel with the inside edge, if such is required. The same pro cess should be gone through on the tongue. As a rule, squares made by firms of repute are per fect, and require no adjusting; nevertheless, it is well to make a critical examination before pur chasing.

Use of the Figures, Lines, and Scales.—The next thing to be considered is the use of the figures, lines, and scales, as exhibited on the square. It is supposed that the ordinary divisions and sub-divisions of the inch, into halves, quar ters, eighths, and sixteenths are understood by the student ; and that he also understands how to use that part of the square that is sub-divided into twelfths of an inch. This being conceded,

we now proceed to describe the various rules as shown on all good squares; but before proceed ing further, it may not be out of place to state, that on the tool recommended in this book, one edge is subdivided into thirty-seconds of an inch.

This fine sub-division will be found very useful, particularly so when used as a scale to measure drawings made in half, quarter, one-eighth, or one-sixteenth of an inch to the foot.

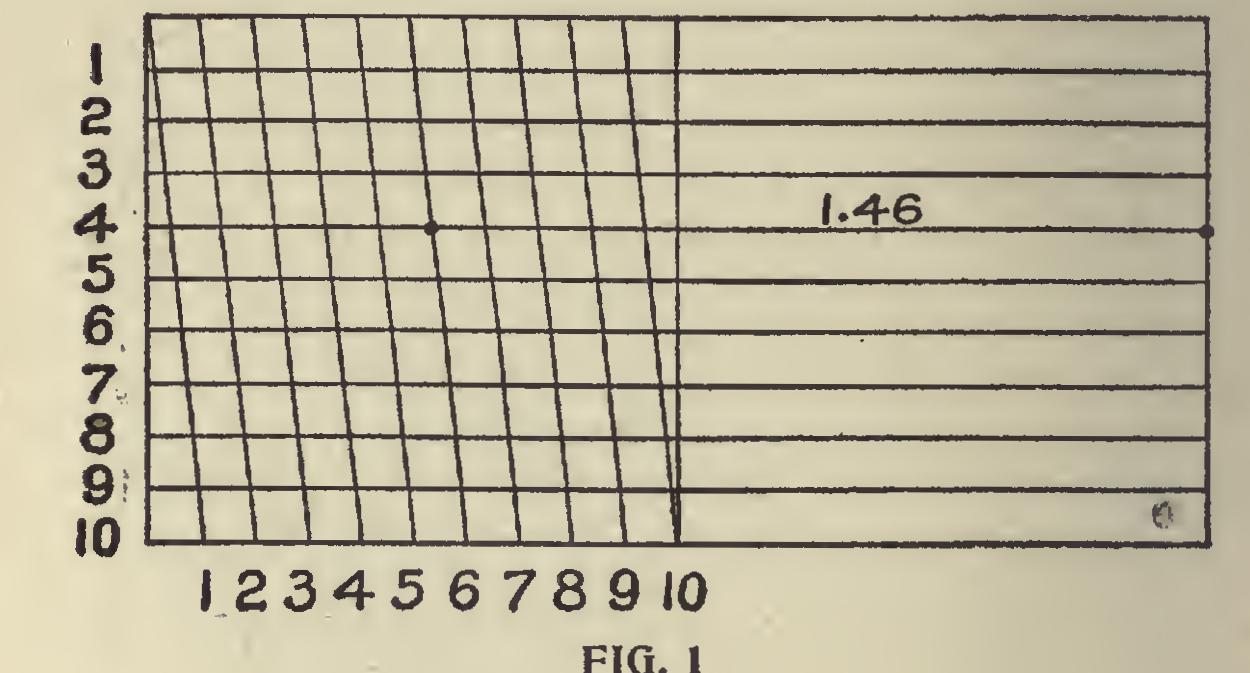

The Diagonal Scale.—In Fig. 1 we show a diagram of the diagonal scale enlarged and let tered for this occasion; and we may here state that the workman will find no difficulty in adapt ing fhe diagrams and what follows to the scale as depicted on his own square.

From the numerous inquiries we have had we are led to believe that the diagonal scale, of which the accompanying figure is a diagram, is not so well understood or appreciated as it ought to be, which is certainly to be regretted. This scale is for minute, measurements, and when a thorough knowledge of its properties is under stood, it is not a very difficult operation to so employ it that the 100th part of an inch may be obtained, and for practical workman this is minute enough, though to the advanced scientist this would be a trifling operation, when such minute measurements are used as the 5000th part of an inch.

In actual practice the scale is never used to find the smaller measurements, but it may some times happen that the workman may want to measure a plan or take a distance on a map very accurately, then a fine subdivision will be found useful.

In order to give the reader a fair understanding of the principles on which this scale is founded, we illustrate its construction and the manner in which it is used, and in doing so, for convenience sake, quote from an ex cellent authority on the subject: "Let us draw a diagram Fig. 2, say three times the size of the first division of the scale as shown on the square. Imagine the short distance from A to B to represent ten inches; it will be evident to any one that to divide that short space into ten equal parts would simply confuse the whole diagram; but if we adopt another plan and divide into ten equal parts its length, as shown, and then draw a diagonal line from B to C, we have the distance AB divided into ten parts.