Brick Construction

mortar and joint

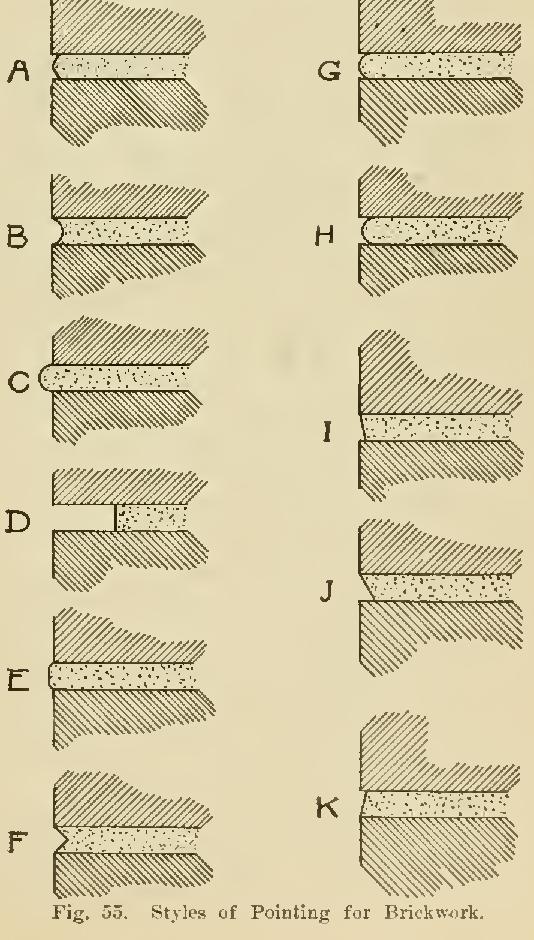

The joint shown at C is much used in pressed-brick work; and that at D is its obverse. These and the other special joints are made with special jointing tools of the desired shape. with the exception of that shown at E. To make this, an iron rod is used the thickness of the joint. This is laid on the face edge of the 'brick already placed, and the mortar is spread out to it. When the mortar has set enough, the rod is removed. Several rods are required.

If mortar is not spread properly, a poor joint will result as shown in Fig. 56 (a and b).

A poor joint is often to be noted in the laying of face brick with "butter" joints. The required thinness of the joint cannot be secured by a full spread of mortar, and the mortar is deposited as shown in Fig. 56 (c), with the result shown hi Fig. 56 (d), where the center is unprotected and there is a risk of spoiling under pressure as indicated by the ragged line.

Flat or Flush Joints. These are formed by pressing with the trowel the wet mortar that protrudes beyond the face, making the joint flat and dash with the wall. A joint of this type may be varied by making Ľa semicircular groove through the central length of the joint, by means of a jointing tool and straight-edge. It is then known as a flat joint jointed.

Strength of Brick Masonry. The strength of brick is sonic indication of the strength of the masonry made from it, but the mortar and the workmanship must also be taken into accomit in making comparisons.

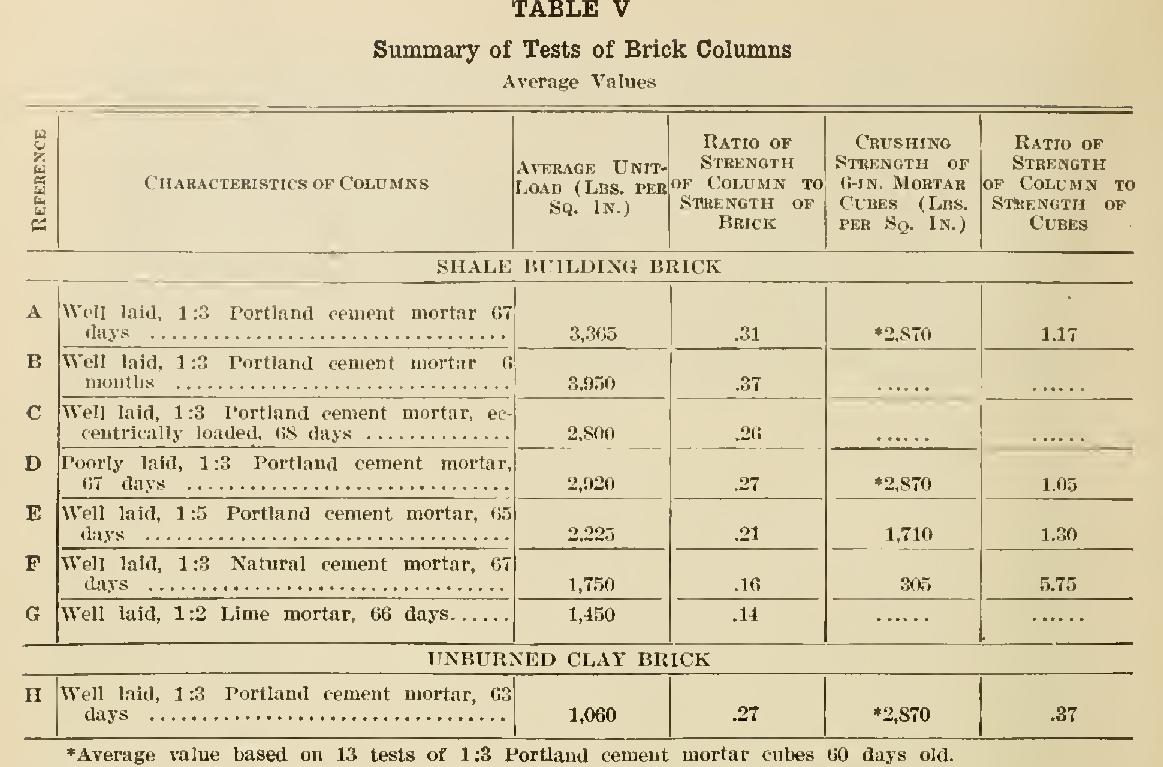

Table V gives results of some recent tests of brick columns made of brick similar to those referred to in Tables III and IV. The columns were inches square, and were from 40 to 43 courses of brick high. The letters at the left refer to groups of several tests. Group H is of under-burned clay brick. The load in C was applied one inch from the center.

The results shown in Table V indicate that both the strength of the individual bricks and that of the mortar are factors in the strength of the columns. As it is the weakest part that fails, it is evident economy to have the strength of the various parts the same.

The building laws of the city of Chicago provide that "brickwork in walls laid in standard Portland cement mortar shall not he loaded more than 25,000 pounds per square foot. Brickwork in an ordinary cement mortar shall not be loaded more than 18,000 pounds per square foot. Brickwork in walls laid in lime mortar shall not be loaded more than 13,000 pounds per square foot." When we consider the results of tests as shown in Table V, it is thus seen that a large factor of safety is allowed in practice.

Brickwork Laid iri Freezing Weather. When it is necessary to lay bricks in freezing weather, there are several ways to counteract the effect of the cold. It should not, however, be assumed that any of the suggested plans are entirely satisfactory. The brick and sand may be heated before being laid; the space to be occupied by the wall may be enclosed within a temporary structure; or the freezing point of the mortar may be lowered by the addition of salt to the water. This last method should be used only when the brick themselves have been warmed so as to remove ice and frost from the surface. Tf this is not done, there will not be firm adhesion between the mortar and the brick.

The rule for mixing mortar for winter use is this: Dissolve one pomul of salt in 18 gallons of water for working in a temperature at freezing point; and for lower temperatures, use one ounce of salt additional for each degree that the temperature is below freezing. Enough salt must he used to prevent the mortar from freezing, whatever the temperature may be.