The Cell in Development and Inheritance

cell-theory and cells

THE CELL IN DEVELOPMENT AND INHERITANCE. Duringthe half-century that has elapsed since the enunciation of the cell-theory by Schleiden and Schwann, in 1838-39, it has become ever more clearly apparent that the key to all ultimate biological problems must, in the last analysis, be sought in the cell. It was the cell-theory that first brought the structure of plants and animals under one point of view by revealing their common plan of organization. It was through the cell-theory that Kolliker and Remak opened the way to an understanding of the nature of embryological development, and the law of genetic continuity lying at the basis of inheritance. It was the cell-theory again which, in the hands of Virchow and Max Schultze, inaugurated a new era in the history of physiology and pathology, by showing that all the various functions of the body, in health and in disease, are but the outward expression of cell-activities. And at a still later day it was through the cell-theory that Hertwig, Fol, Van Beneden, and Strasburger solved the long-standing riddle of the fertilization of the egg, and the mechanism of hereditary transmission. No other biological generalization, save only the theory of organic evolution, has brought so many apparently diverse phenomena under a common point of view or has accomplished more for the unification of knowledge. The cell-theory must therefore be placed beside the evolution-theory as one of the foundation stones of modern biology.

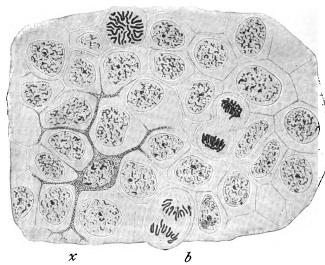

And yet the historian of latter-day biology cannot fail to be struck with the fact that these two great generalizations, nearly related as they are, have been developed along widely different lines of research, and have only within a very recent period met upon a common ground. The theory of evolution originally grew out of the study of natural history, and it took definite shape long before the ultimate structure of living bodies was in any degree comprehended. The evolutionists of the Lamarckian period gave little heed to the finer details of internal organization. They were concerned mainly with the more obvious characters of plants and animals—their forms, colours, habits, distribution, their anatomy and embryonic development and with the systems of classification based upon such characters ; and long afterwards it was, in the main, the study of like characters with reference to their historical origin that led Darwin to his splenFig. z. —A portion of the epidermis of a larval salamander (Amblystorna) as seen in slightly oblique horizontal section, enlarged 55o diameters. Most of the cells are polygonal in form, contain large nuclei, and are connected by delicate protoplasmic bridges. Above x is a branched, dark pigment-cell that has crept up from the deeper layers and lies between the epidermal cells. Three of the latter are undergoing division, the earliest stage (spreme) at a, a later stage (mitotic figure in the anaphase) at b, showing the chromosomes, and a final stage (telophase), showing fission of the cell-body, to the right.

did triumphs. The study of microscopical anatomy, on which the cell-theory was based, lay in a different field. It was begun and long carried forward with no thought of its bearing on the origin of living forms ; and even at the present day the fundamental problems of organization, with which the cell-theory deals, are far less accessible to historical inquiry than those suggested by the more obvious external characters of plants and animals. Only within a few years, indeed, has the ground been cleared for that close alliance of the evolutionists and the cytologists which forms so striking a feature of contemporary biology. We may best examine the steps by which

this alliance has been effected by an outline of the cell-theory, followed by a brief statement of its historical connection with the evolution-theory.

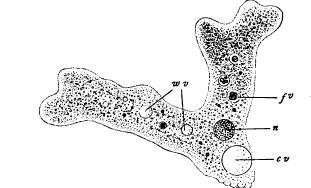

During the past thirty years, the theory of organic descent has been shown, by an overwhelming mass of evidence, to be the only tenable conception of the origin of diverse living forms, however we may conceive the causes of the process. While the study of general zoology and botany has systematically set forth the results, and in a measure the method, of organic evolution, the study of microscopical anatomy has shown us the nature of the material on which it has operated, demonstrating that the obvious characters of plants and animals are but varying expressions of a subtle interior organization common to all. In its broader outlines the nature of this organization is now accurately determined ; and the " cell-theory," by which it is formulated, is, therefore, no longer of an inferential or hypothetical character, but a generalized statement of observed fact which may be outlined as follows: In all the higher forms of life, whether plants or animals, the body may be resolved into a vast host of minute structural units known as cells, out of which, directly or indirectly, every part is built (Fig. I). The substance of the skin, of the brain, of the blood, of the bones or muscles or any other tissue, is not homogeneous, as it appears to the unaided eye. The microscope shows it to be an aggregate composed of innumerable minute bodies, as if it were a colony or congeries of organisms more elementary than itself. These elementary bodies, the cells, are essentially minute masses of living matter or protoplasm, a substance characterized by Huxley many years ago as the "physical basis of life " and now universally recognized as the immediate substratum of all vital action. Endlessly diversified in the details of their form and structure, cells nevertheless possess a characteristic type of organization common to them all ; hence, in a certain sense, they may be regarded as elementary organic units out of which the body is compounded. In the lowest forms of life the entire body consists of but a single cell (Fig. 2). In the higher multicellular forms the body consists of a multitude of such cells associated in one organic whole. Structurally, therefore, the multicellular body is in a certain sense comparable with a colony or aggregation of the lower one-celled forms.' From the physiological point of view a like comparison may be drawn. In the one-celled forms all of the vital functions are performed by a single cell ; in the higher types they are distributed by a physiological division of labour among different groups of cells specially devoted to the performance of specific functions. The cell is therefore not only a unit of structure, but also a unit of function. " It is the cell to which the consideration of every bodily function sooner or later drives us. In the musclecell lies the riddle of the heart-beat, or of muscular contraction ; in the gland-cell are the causes of secretion ; in the epithelial cell, in the white blood-cell, lies the problem of the absorption of food, and the secrets of the mind are slumbering in the ganglion-cell. . . . If then physiology is not to rest content with the mere extension of our fig. 2.— Amaeda Proteas,an animal consisting of a single naked cell, x 380. (From Sedgwick and Wilson's Biology.) e. The nucleus ; m.v. Water-vacuoles ; c.v. Contractile vacuole ; f.v. Food-vacuole.