The Cell in Development and Inheritance

body and germ-cells

acters ; i.e. changes that arise in the course of the individual life as the effect of use and disuse, or of food, climate, and the like. The inheritance of congenital characters is now universally admitted, but it is otherwise with acquired characters. The inheritance of the latter, now the most debated question of biology, had been taken for granted by Lamarck a half-century before Darwin ; but he made no attempt to show how such transmission is possible. Darwin, on the other hand, squarely faced the physiological requirements of the problem, recognizing that the transmission of acquired characters can only be possible under the assumption that the germ-cell definitely reacts to all other cells of the body in such wise as to register the changes taking place in them. In his ingenious and carefully elaborated theory of Darwin framed a provisional physiological hypothesis of inheritance in accordance with this assumption, suggesting that the germ-cells are reservoirs of minute germs or gemmules derived from every part of the body ; and on this basis he endeavoured to explain the transmission both of acquired and of congenital variations, reviewing the facts of variation and inheritance with wonderful skill, and building up a theory which, although it forms the most speculative and hypothetical portion of his writings, must always be reckoned one of his most interesting contributions to science.

The theory of pangenesis has been generally abandoned in spite of the ingenious attempt to remodel it made by Brooks in In the same year the whole aspect of the problem was changed, and a new period of discussion inaugurated by Weismann, who put forth a bold challenge of the entire Lamarckian " I do not propose to treat of the whole problem of heredity, but only of a certain aspect of it, — the transmission of acquired characters, which has been hitherto assumed to occur. In taking this course I may say that it was impossible to avoid going back to the foundation of all phenomena of heredity, and to determine the substance with which they must be connected. In my opinion this can only be the substance of the germ-cells ; and this substance transfers its hereditary tendencies from generation to generation, at first unchanged, and always uninfluenced in any corresponding manner, by that which happens during the life of the individual which bears it. If these views be correct, all our ideas upon the transformation of species require thorough modification, for the whole principle of evolution by means of exercise (use and disuse) as professed by Lamarck, and accepted in some cases by Darwin, entirely collapses " p. 69).

It is impossible, he continues, that acquired traits should be transmitted, for it is inconceivable that definite changes in the body, or " soma," should so affect the protoplasm of the germ-cells, as to cause corresponding changes to appear in the offspring. How, he asks, can

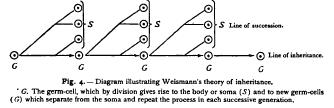

the increased dexterity and power in the hand of a trained pianoplayer so affect the molecular structure of the germ-cells as to produce a corresponding development in the hand of the child ? It is a physiological impossibility. If we turn to the facts, we find, Weismann affirms, that not one of the asserted cases of transmission of acquired characters will stand the test of rigid scientific scrutiny. It is a reversal of the true point of view to regard inheritance as taking place from the body of the parent to that of the child. The child inherits from the parent germ-cell, not from the parent-body, and the germ-cell owes its characteristics not to the body which bears it, but to its descent from a pre-existing germ-cell of the same kind. Thus the body is, as it were, an offshoot from the germ-cell (Fig. 4). As far as inheritance is concerned, the body is merely the carrier of the germ-cells, which are held in trust for coming generations.

Weismann's subsequent theories, built on this foundation, have given rise to the most eagerly contested controversies of the postDarwinian period, and, whether they are to stand or fall, have played a most important part in the progress of science. For aside from the truth or error of his special theories, it has been Weismann's great service to place the keystone between the work of the evolutionists and that of the cytologists, and thus to bring the cell-theory and the evolution-theory into organic connection. It is from this point of view that the present volume has been written. It has been my endeavour to treat the cell primarily as the organ of inheritance and development ; but, obviously, this aspect of the cell can only be apprehended through a study of the general phenomena of cell-life. The order of treatment, which is a convenient rather than a strictly logical one, is as follows : The opening chapter is devoted to a general sketch of cell-structure, and the second to the phenomena of cell-division. The following three chapters deal with the germ-cells, — the third with their structure and mode of origin, the fourth with their union in fertilization, the fifth with the phenomena of maturation by which they are prepared for their union. The sixth chapter contains a critical discussion of cell-organization, completing the morphological analysis of the cell. In the seventh chapter the cell is considered with reference to its more fundamental chemical and physiological properties as a prelude to the examination of development which follows. The succeeding chapter approaches the objective point of the book by considering the cleavage of the ovum and the general laws of cell-division of which it is an expression. The ninth chapter, finally, deals with the elementary operations of development considered as cell-functions and with the theories of inheritance and development based upon them.