The Cell in Development and Inheritance

cells and egg

But although the external nature of development was thus determined, the actual structure of the egg and the mechanism of inheritance remained for nearly a century in the dark. It was reserved for Schwann (1839) and his immediate followers to recognize the fact, conclusively demonstrated by all later researches, that the is a cell having the same essential structure as other cells of the body. And thus the wonderful truth became manifest that a single cell may contain within its microscopic compass the sum-total of the heritage of the species. This conclusion first reached in the case of the female sex was soon afterwards extended to the male as well. Since the time of Leeuwenhoek (1677) it had been known that the sperm or fertilizing fluid contained innumerable minute bodies endowed in nearly all cases with the power of active movement, and therefore regarded by the early observers as parasitic animalcules or infusoria, a view which gave rise to the name spermatozoa (sperm-animals) by which they are still generally known.' As long ago as 1786, however, it was shown by Spallanzani that the fertilizing power must lie in the spermatozoa, not in the liquid in which they swim, because the spermatic fluid loses its power when filtered. Two years after the appearance of Schwann's epoch-making work Kolliker demonstrated (1841) that the spermatozoa arise directly from cells in the testis, and hence cannot be regarded as parasites, but are, like the ovum, derived from the parent-body. Not until 1865, however, was the final proof attained by SchweiggerSeidel and La Valette St. George that the spermatozoon contains not only a nucleus, as Kolliker believed, but also cytoplasm. It was thus shown to be, like the egg, a single cell, peculiarly modified in structure, it is true, and of extraordinary minuteness, yet on the whole morphologically equivalent to other cells. A final step was taken ten years later (1875), when Oscar Hertwig established the all-important fact that fertilization of the egg is accomplished by its union with one spermatozoon, and one only. In sexual reproduction, therefore, each sex contributes a single cell of its own body to the formation of the offspring, a fact which beautifully tallies with the conclusion of Darwin and Galton that the sexes play, on the whole, equal, though not identical parts in hereditary transmission. The ultimate problems of sex, fertilization, inheritance, and development were thus shown to be cell problems.

Meanwhile, during the years immediately following the announcement of the cell-theory the attention of investigators was especially focussed upon the question : How do the cells of the body arise ? Schwann and Schleiden held that cells might arise in two different ways ; viz. either by the division or fission of a pre-existing mothercell, or by " free cell-formation," new cells arising in the latter case not from pre-existing cells, but by crystallizing, as it were, out of a formative or nutritive substance, termed the " cytoblastema." It was only after many years of painstaking research that " free cell' The discovery of the spermatozoa is generally accredited to Ludwig Hamm, a pupil.

of Leeuwenhoek (1677), though Hartsoeker afterwards claimed the merit of having seen them as early as 1674 (Dr. Allen Thomson).

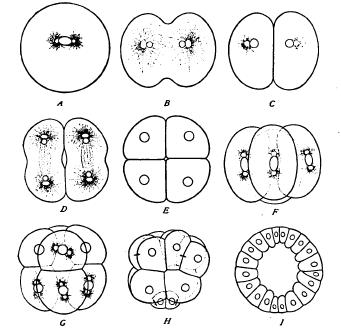

formation " was absolutely proved to be a myth, though many of Schwann's immediate followers threw doubts upon it, and as early as 1855 Virchow positively maintained the universality of cell-division, contending that every cell is the offspring of a pre-existing parent-cell, and summing up in the since famous aphorism, "omnis Fig. 3.— Cleavage of the ovum of the sea-urchin Toxotneuties, x 330, from life. The suc

cessive divisions up to the i6-cell stage (H) occupy about two hours. / is a section of the embryo (blastula) of three hours, consisting of approximately 128 cells surrounding a central cavity or blastoccel.

cellula e cellula." At the present day this conclusion rests upon a foundation so firm that we are justified in regarding it as a universal law of development.

Now, if the cells of the body always arise by the division of preexisting cells, all must be traceable back to the fertilized egg-cell as their common ancestor. Such is, in fact, the case in every plant and animal whose development is accurately known. The first step in development consists in the division of the egg into two parts, each of which is a cell, like the egg itself. The two then divide in turn to form four, eight, sixteen, and so on in more or less regular progression (Fig. 3) until step by step the egg has split up into the multitude of cells which build the body of the embryo, and finally of the adult. This process, known as the cleavage or segmentation of the egg, was observed long before its meaning was understood. It seems to have been first definitely described in the case of the frog's egg, by Prevost and Dumas (1824), though earlier observers had seen it ; but at this time neither the egg nor its descendants were known to be cells, and its true meaning was first clearly perceived by Bergmann, Kolliker, Reichert, von Baer, and Remak, some twenty years later. The interpretation of cleavage as a process of cell-division was followed by the demonstration that cell-division does not begin with cleavage, but can be traced back into the foregoing generation; for the egg-cell, as well as the sperm-cell, arises by the division of a cell preexisting in the parent-body. It is therefore derived by direct descent from an egg-cell of the foregoing generation, and so on ad infinitum. Embryologists thus arrived at the conception so vividly set forth by Virchow in of an uninterrupted series of cell-divisions extending backward from existing plants and animals to that remote and unknown period when vital organization assumed its present form. Life is a continuous stream. The death of the individual involves no breach of continuity in the series of cell-divisions by which the life of the race flows onwards. The individual body dies, it is true, but the germ-cells live on, carrying with them, as it were, the traditions of the race from which they have sprung, and handing them on to their descendants.

These facts clearly define the problems of heredity and variation as they confront the investigator of the present day. All theories of evolution take as fundamental postulates the facts of variation and heredity ; for it is by variation that new characters arise and by heredity that they are perpetuated. Darwin recognized two kinds of variation, both of which, being inherited and maintained through the conserving action of natural selection, might give rise to a permanent transformation of species. The first of these includes congenital or inborn variations ; i.e. such as appear at birth or are developed "spontaneously," without discoverable connection with the activities of the organism itself or the direct effect of the environment upon it. In a second class of variations are placed the so-called acquired char1 See the quotation from the original edition of the Cellularpathologre at the head of Chapter II., p. 45.