The Cytoplasm

fig and structure

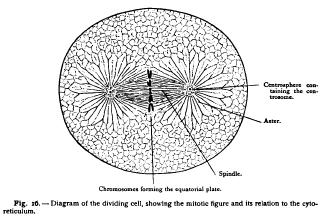

Nowhere, however, is the thread-work shown with such beauty as in dividing-cells, where (Figs. 16, 24) the fibrillae group themselves in two radiating systems or asters, which are in some manner the immediate agents of cell-division. Similar radiating systems of fibres occur in amceboid cells, such as leucocytes (Fig. 35) and pigmentcells (Fig. 36), where they probably form a contractile system by means of which the movements of the cell are performed.

The views of Butschli and his followers, which have been touched on at p. 18, differ considerably from the foregoing, the fibrillm being regarded as the optical sections of thin plates or lamellae which form the walls of closed chambers filled by a more liquid substance. Butschli, followed by Reinke, Eismond, Erlanger, and others, interprets in the same sense the astral systems of dividingcells which are regarded as a radial configuration of the lamellae about a central point (Fig. 8, B). Strong evidence against this view is, I believe, afforded by the appearance of the spindle and asters in cross-section. In the early stages of the egg of 'Wel-cis, for example, the astral rays are coarse anastomosing fibres that stain intensely and are therefore very favourable for observation (Fig. 43). That they are actual fibres is, I think, proved by sagittal sections of the asters in which the rays are cut at various angles. The 1 The structure of the ciliated cell, as described by Engelmann, may be beautifully demonstrated in the funnel-cells of the nephridia and sperm-ducts of the earthworm.

cut ends of the branching rays appear in the clearest manner, not as plates but as distinct dots, from which in oblique sections the ray may be traced inwards towards the centrosphere. Droner, too, figures the spindle in cross-section as consisting of rounded dots, like the end of a bundle of wires, though these are connected by cross-branches (Fig. 22, F). Again, the crossing of the rays proceeding from the asters (Fig. 69), and their behaviour in certain phases of cell-division, is difficult to explain under any other than the fibrillar theory.

We must admit, however, that the network varies greatly in different cells and even in different physiological phases of the same cell ; and that it is impossible at present to bring it under any rule of universal application. It is possible, nay probable, that in one and the same cell a portion of the network may form a true alveolar structure such as is described by Butschli, while other portions may, at the same time, be differentiated into actual fibres. If this be true the fibrillar or alveolar structure is a matter of secondary moment, and the essential features of protoplasmic organization must be sought in a more subtle underlying structure.'