Conjugation in Unicellular Forms

nuclei and degeneration

CONJUGATION IN UNICELLULAR FORMS The conjugation of unicellular organisms possesses a peculiar interest, since it is undoubtedly a prototype of the union of germ-cells in the multicellular forms. Butschli and Minot long ago maintained that cell-divisions tend to run in cycles, each of which begins and ends with an act of conjugation. In the higher forms the cells produced in each cycle cohere to form the multicellular body ; in the unicellular forms the cells separate as distinct individuals, but those belonging to one cycle are collectively comparable with the multicellular body. The validity of this comparison, in a morphological sense, is generally admitted.' No process of conjugation, it is true, is known to occur in many unicellular and in some multicellular forms, and the cyclical character of cell-division still remains sub It is none the less certain that a key to the fertilization of higher forms must be sought in the conjugation of unicellular organisms.

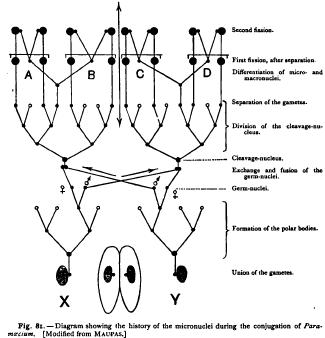

The difficulties of observation are, however, so great that we are as yet acquainted with only the outlines of the process, and have still no very clear idea of its finer details or its physiological meaning. The phenomena have been most closely followed in the Infusoria by Butschli, Maupas, and Richard Hertwig, though many valuable observations on the conjugation of unicellular plants have been made by De Bary, Schmitz, Klebahn, and Overton. All these observers have reached the same general result as that attained through study of the fertilization of the egg ; namely, that an essential phenomenon of conjugation is a union of the nuclei of the conjugating cells. Among the unicellular plants both the cell-bodies and the nuclei completely fuse. Among animals this may occur ; but in many of the Infusoria union of the cell-bodies is only temporary, and the conjugation consists of a mutual exchange and fusion of nuclei. It is X and Y represent the opposed macro- and micronuclei in the two respective gametes ; circles represent degenerating nuclei ; black dots, persisting nuclei.

impossible within the limits of this work to attempt more than a sketch of the process in a few forms.

We may first consider the conjugation of Infusoria. Maupas's beautiful observations have shown that in this group the life-history of the species runs in cycles, a long period of multiplication by celldivision being succeeded by an "epidemic of conjugation," which inaugurates a new cycle, and is obviously comparable in its physiological aspect with the union of germ-cells in the Metazoa. If conjugation do not occur, the race rapidly degenerates and dies out ; and Maupas believes himself justified in the conclusion that conjugation counteracts the tendency to senile degeneration and causes rejuvenescence, as maintained by Biitschli and Minot.' In Stylonychia pustulata, which Maupas followed continuously from the end of February until July, the first conjugation occurred on April 29th, after 128 bi-partitions; and the epidemic reached its height three weeks later, after 175 bi-partitions. The descendants of individuals prevented from conjugation died out through "senile degeneracy," after 316 bi-partitions. Similar facts were observed in many other forms. The degeneracy is manifested by a very marked reduction in size, a partial atrophy of the cilia, and especially by a more or less complete degradation of the nuclear apparatus. In Stylonychia pustulata and Onychodrontus grandis this process especially affects the micronucleus, which atrophies, and finally disappears, though the animals still actively swim, and for a time divide. Later, the macronucleus becomes irregular, and sometimes breaks up into smaller bodies. In other cases, the degeneration first affects the macronucleus, which may lose its chromatin, undergo fatty degeneration, and may finally disappear altogether (Stylonychia mytilus), after which the micronucleus soon degenerates more or less completely, and the race dies. It is a very significant fact that towards the end of the cycle, as the nuclei degenerate, the animals become incapable of taking food and of growth ; and it is probable, as Maupas points out, that the degeneration of the cytoplasmic organs is due to disturbances in nutrition caused by the degeneration of the nucleus.