Conjugation in Unicellular Forms

chromatophore and cells

It is an interesting fact that in Noctiluca, in the Gregarines, and probably in some other Protozoa, conjugation is followed by a very rapid multiplication of the nucleus followed by a corresponding division of the cell-body to form " spores," which remain for a time closely aggregated before their liberation. The resemblance of this process to the fertilization and subsequent cleavage of the ovum is particularly striking.

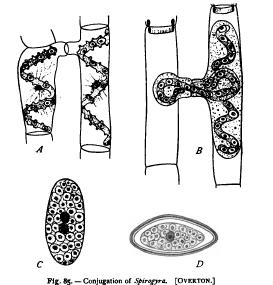

The conjugation of unicellular plants shows some interesting A. Union of the conjugating cells (S. communis). B. The typical, though not invariable, mode of fusion in S. Weberi; the chromatophore of the " female " cell breaks in the middle, while that of the " male " cell passes into the interval. C. The resulting zygospore filled with pryrenoids, before union of the nuclei. D. Zygospore after fusion of the nuclei and formation of the membrane.

features. Here the conjugating cells completely fuse to form a " zygospore " (Figs. 85, 99), which as a rule becomes surrounded by a thick membrane, and, unlike the animal conjugate, may long remain in a quiescent state before division. Not only do the nuclei unite, but in many cases the plastids also (chromatophores). In Spirogyra some interesting variations in this regard have been observed. In some species De Bary has observed that the long band-shaped chromatophores unite end to end so that in the zygote the paternal and maternal chromatophores lie at opposite ends. In S. Weberi, on the other hand, Overton has found that the single maternal chromatophore breaks in two in the middle and the paternal chromatophore is interpolated between the two halves, so as to lie in the middle of the zygote (Fig. 85). It follows from this, as De Vries has pointed out, that the origin of the chromatophores in the daughter-cells differs in the two species, for in the former case one receives a maternal, the other a paternal, chromatophore, while in the latter, the chromatophore of each daughter-cell is equally derived from those of the two gametes. The final result is, however, the same ; for, in both cases, the chromatophore of the zygote divides in the middle at each ensuing division. In the first case, therefore, the maternal chromatophore passes into one, the paternal into the other, of the daughter-cells. In the second case the same result is effected by two succeeding divisions, the two middle-cells of the four-celled band receiving paternal, the two end-cells maternal, chromatophores. In the case of a Spirogyra filament having a single chromatophore it is therefore "wholly immaterial whether the individual cells receive the chlorophyll-band from the father or the mother" (De Vries), — a result which, as Wheeler has pointed out, is in a measure analogous to that reached in the case of the centrosome of the animal egg.' All forms of fertilization involve a conjugation of cells by a process that is the exact converse of cell-division. In the lowest forms, such as the unicellular algae, the conjugating cells are, in a morphological sense, precisely equivalent, and conjugation takes place between corresponding elements, nucleus uniting with nucleus, cell-body with cell-body, and even, in some cases, plastid with plastid.

Whether this is true of the centrosomes is not known, but in the Infusoria there is a conjugation of the achromatic spindles which certainly points to a union of the centrosomes or their equivalents. As we rise in the scale, the conjugating cells diverge more and more, until in the higher plants and animals they differ widely not only in form and size, but also in their internal structure, and to such an extent that they are no longer equivalent either morphologically or physiologically. Both in animals and in plants the paternal germcell loses most of its cytoplasm, the main bulk of which, and hence the main body of the embryo, is now supplied by the egg. But, 1 De Vries's conclusion is, however, not entirely certain; for it is impossible to determine, save by analogy, whether the chromatophores maintain their individuality in the zygote.

more than this, the germ-cells come to differ in theit morphological composition ; for in plants the male germ-cell loses its plastids, which are supplied by the mother alone, while in most if not all animals the egg loses its centrosome, which is then supplied by the father. The loss of the centrosome by the egg is, I believe, to be regarded as a provision to guard against parthenogenesis and to ensure amphimixis.

The equivalence of the germ-cells is thus finally lost. Only the germ-nuclei retain their primitive morphological equivalence. Hence we find the essential fact of fertilization and sexual reproduction to be a union of equivalent nuclei ; and to this all other processes are tributary. The substance of the germ-nuclei, giving rise to the same number of chromosomes in each, is equally distributed to the daughter-cells and probably to all the cells of the body.

As regards the most highly differentiated type of fertilization and development we thus reach the following conception : From the mother comes in the main the cytoplasm of the embryonic body which is the principal substratum of growth and differentiation. From both parents comes the hereditary basis or chromatin by which these processes are controlled and from which they receive the specific stamp of the race. From the father comes the centrosome to organize the machinery of mitotic division by which the egg splits up into the elements of the tissues, and by which each of these elements receives its quota of the common heritage of chromatin. Huxley hit the mark two score years ago when in the words that head this chapter he compared the organism to a web of which the warp is derived from the female and woof from the male. What has since been gained is the knowledge that this web is to be sought in the chromatic substance of the nuclei, and that the centrosome is the builder of the loom.