Geometrical Relations of Cleavage-Forms

cells and cleavage

This simple and regular mode of division forms a type to which nearly all forms of cleavage may be referred ; but the order and form of the divisions is endlessly varied by special conditions. These modifications are all referable to the three following causes : 1. Disturbances in the rhythm of division.

2. Displacement of the cells.

3. Unequal division of the cells.

The first of these requires little comment. Nothing is more common than a departure from the mathematical regularity of division. The variations are sometimes quite irregular, sometimes follow a definite law, as, for instance, in the annelid Nereis (Fig. 122), where the typical succession in the number of cells is with great constancy 2, 4, 8, 16, 20, 23, 29, 32, 37, 38, 41, 42, after which the order is more or less variable. The meaning of such variations in particular cases is not very clear. They are certainly due in part to variations in the amount of deutoplasm ; for, as Balfour long since pointed out ('75), the rapidity of division in any part of the ovum is in general inversely proportional to the amount of deutoplasm it contains. Exceptions to this law are, however, known.

The second series of modifications, due to displacements of the cells, are probably due to mutual pressure, however caused,' which leads them to take up the position of least resistance or greatest economy of space. In this regard the behaviour of tissue-cells in general has been shown to conform on the whole to that of elastic spheres, such as soap-bubbles when massed together and free to move. Such bodies, as Plateau and Lamarle have shown, assume a polyhedral form and tend towards such an arrangement that the area of surface-contact between them is a minimum. Spheres in a mass thus tend to assume the form of interlocking polyhedrons so arranged that three planes intersect in a line, while four lines and six planes meet at a point. If arranged in a single layer on an extended surface they assume the form of hexagonal prisms, three planes meeting along a line as before. Both these forms are commonly shown in the arrangement of the cells of plant and animal tissues ; and Berthold ('86) and Errara ('86, '87) have pointed out that in almost all cases the cells tend to alternate or interlock so as to reduce the contact-arca to a minimum. Thus arise many of the most frequent modifications

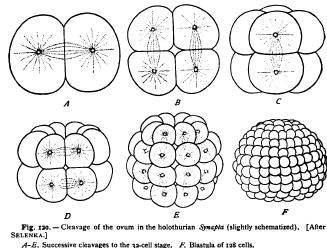

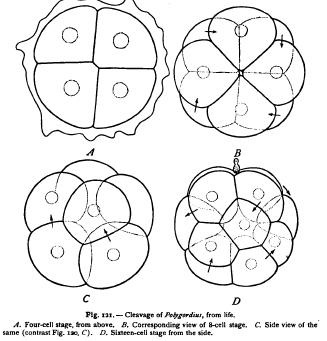

of cleavage. Sometimes, as in Synapta, the alternation of the cells is effected through displacement of the blastomeres after their formation. More commonly it arises during the division of the cells and may even be predetermined by the position of the mitotic figures before the slightest external sign of division. Thus arises that form of cleavage known as the spiral, oblique, or alternating type, where the blastomeres interlock during their formation and lie in the position of least resistance from the beginning. This form of cleavage, especially characteristic of many worms and mollusks, is typically shown by the egg of Polygordius (Fig. 121). The four-celled stage is nearly like that of Synapta, though even here the cells slightly interlock. The third division is, however, oblique, the four upper cells being virtually rotated to the right (with the hands of a watch) so as to alternate with the four lower ones. The fourth cleavage is likewise oblique, but at right angles to the third, so that all of the cells interlock as shown in Fig. 121, D. This alternation regularly recurs in the later cleavages.

This form of cleavage beautifully illustrates Sachs's second law operating under modified conditions, and the conclusion is irresistible that the modification is at bottom a result of the same forces as those operating in the case of soap-bubbles. In many worms and mollusks the obliquity of cleavage appears still earlier, at the second cleavage, the four cells being so arranged that two of them meet along a " crossfurrow " at the lower pole of the egg, while the other two meet at the upper pole along a similar, though often shorter, cross-furrow at right angles to the lower (e.g. in Nereis, Fig. 122). It is a curious fact that the direction of the displacement is extremely constant, the upper quartet in the eight-cell stage being rotated in all but a few cases to the right, or with the hands of a watch. Crampton ('94) has discovered the remarkable fact that in Physa, a gasteropod having a reversed or sinistral shell, the whole order of displacement is likewise reversed.