Geometrical Relations of Cleavage-Forms

division and cleavage

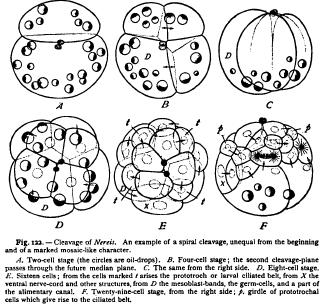

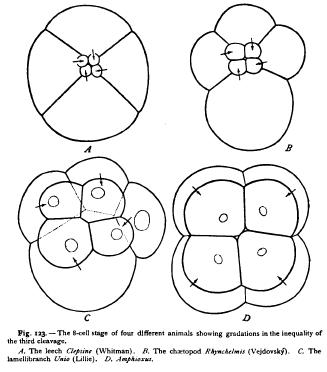

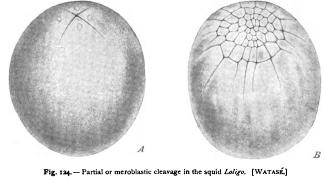

The third class of modifications, due to unequal division of the cells, leads to the most extreme types of cleavage. Such divisions appear sooner or later in all forms of cleavage, the perfect equality so long maintained in Synapta being a rare phenomenon. The period at which the inequality first appears varies greatly in different forms. In Polygordius (Fig. 121) the first marked inequality appears at the fifth cleavage ; in sea-urchins it appears at the fourth (Fig. 3); in Amphioxus at the third (Fig. 123); in the tunicate Clavelina at the second (Fig. 126); in Nereis at the first division (Figs. 43, 122). The extent of the inequality varies in like manner. Taking the third cleavage as a type, we may trace every transition from an equal division (echinoderms, Polygordius), through forms in which it is but slightly marked (Amphioxus, frog), those in which it is conspicuous (Nereis, Lymmea, Polyclades, Petromyzon, etc.), to forms such as Clepsine, where the cells of the upper quartet are so minute as to appear like mere buds from the four large lower cells (Fig. 123). At the extreme of the series we reach the partial or meroblastic cleavage, such as occurs in the cephalopods, in many fishes, and in birds and reptiles. Here the lower hemisphere of the egg does not divide at all, or only at a late period, segmentation being confined to a disclike region or blastoderm at one pole of the egg (Fig. 124).

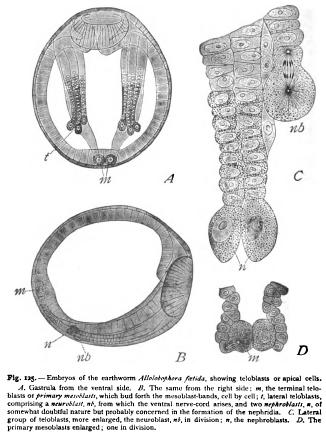

Very interesting is the case of the teloblasts or pole-cells characteristic of the development of many annelids and mollusks and found in some arthropods. These remarkable cells are large blastomeres, set aside early in the development, which bud forth smaller cells in regular succession at a fixed point, thus giving rise to long cords of cells (Fig. 125). The teloblasts are especially characteristic of apical growth, such as occurs in the elongation of the body in annelids, and they are closely analogous to the apical cells situated at the growing point in many plants, such as the ferns and stoneworts.

Unequal division still awaits an explanation. The fact has already been pointed out (p. 51) that the inequality of the daughter-cells is preceded, if not caused, by an inequality of the asters ; but we are still almost entirely ignorant of the ultimate cause of this inequality. In the cleavage of the animal egg unequal division is closely connected with the distribution of yolk — a fact generalized by Balfour in the statement ('8o) that the size of the cells formed in cleavage varies inversely to the relative amount of protoplasm in the region of the egg from which they arise. Thus, in all telolecithal ova, where the deutoplasm is mainly stored in the lower or vegetative hemisphere, as in many worms, mollusks, and vertebrates, the cells of the upper or protoplasmic hemisphere are smaller than those of the lower, and may be distinguished as micromeres from the larger macromeres of the lower hemisphere. The size-ratio between micromeres and macromeres is on the whole directly proportional to the ratio between protoplasm and deutoplasm. Partial or discoidal cleavage occurs

when the mass of deutoplasm is so great as entirely to prevent cleavage in the lower hemisphere.

Balfour's law undoubtedly explains a large number of cases, but by no means all ; for innumerable cases are known in which no correlation can be made out between the distribution of inert substance and the inequality of division. This is the case, for example, with the teloblasts mentioned above, which contain no deutoplasm, yet regularly divide unequally. It seems to be inapplicable to the inequalities of the first two divisions in annelids and gasteropods. It is conspicuously inadequate in the history of individual blastomeres, where the history of division has been accurately determined. In Nereis, for example, a large cell known as the first somatoblast, formed at the fourth cleavage (X, Fig. 122, E), undergoes an invariable order of division, three unequal divisions being followed by an equal one, then by three other unequal divisions, and again by an equal. This cell contains no deutoplasm and undergoes no perceptible changes of substance. The cause of the definite succession of equal and unequal divisions is here wholly unexplained.

Such cases prove that Balfour's law is only a partial explanation, and is probably the expression of a more deeply lying cause, and there is reason to believe that this cause lies outside the immediate mechanism of mitosis. Conklin ('94) has called attention to the fact 1 that the immediate cause of the inequality probably does not lie either in the nucleus or in the amphiaster ; for not only the chromatin-halves, but also the asters, are exactly equal in the early prophases, and the inequality of the asters only appears as the division proceeds. Probably, therefore, the cause lies in some relation between the mitotic figure and the cell-body in which it lies. I believe there is reason to accept the conclusion that this relation is one of position, however caused. A central position of the mitotic figure results in an equal division ; an eccentric position caused by a radial movement of the mitotic figure, in the direction of its axis towards the periphery, leads to unequal division, and the greater the eccentricity, the greater the inequality, an extreme form being beautifully shown in the formation of the polar bodies. Here the original amphiaster is perfectly symmetrical, with the asters of equal size (Fig. 71, A). As the spindle rotates into its radial position and approaches the periphery, the development of the outer aster becomes, as it were, suppressed, while the central aster becomes enormously large. The size of the aster, in other words, depends upon the extent of the cytoplasmic area that falls within the sphere of influence of the centrosome ; and this area depends upon the position of the centrosome. If, therefore, the polar amphiaster could be artificially prevented from moving to its peripheral position, the egg would probably divide equally.