On the Nature and Causes of Differentiation

egg and cells

ON THE NATURE AND CAUSES OF DIFFERENTIATION We have now cleared the ground for a restatement of the problem of development, and an examination of the views opposed to the Roux-Weismann theory. After discarding the hypothesis of qualitative division the problem confronts us in the following form. If chromatin be the idioplasm in which inheres the sum-total of hereditary forces, and if it be equally distributed at every cell-division, how can its mode of action so vary in different cells as to cause diversity of structure, i.e. differentiation? It is perfectly certain that differentiation is an actual progressive transformation of the egg-substance involving both physical and chemical changes, occurring in a definite order, and showing a definite distribution in the regions of the egg. These changes are sooner or later accompanied by the cleavage of the egg into cells whose boundaries may sharply mark the areas of differentiation. What gives these cells their specific character? Why, in the four-cell stage of an annelid egg, should the four cells contribute equally to the formation of the alimentary canal and the cephalic nervous system, while only one of them (the lefthand posterior) gives rise to the nervous system of the trunk-region and to the muscles, connective tissues, and the germ-cells? (Figs. 1 22, 137, B). There cannot be a fixed and necessary relation of cause and effect between the various regions of the egg which these blastomeres represent and the adult parts arising from them ; for, as we have seen, these relations may be artificially altered. A portion of the egg which under normal conditions would give rise to only a fragment of the body will, if split off from the rest, give rise to an entire body of diminished size. What then determines the history of such a portion ? What influence moulds it now into an entire body, now into a part of a body ? De Vries, in his remarkable essay on Intracellular Pangenesis ('89), endeavoured to cut this Gordian knot by assuming that the character of each cell is determined by pangens that migrate from the nucleus into the cytoplasm, and, there becoming active, set up specific changes and determine the character of the cell, this way or that, according to their nature. But what influence guides the migration of the pangens, and so correlates the operations of development ? Both Driesch and Oscar Hertwig have attempted to answer this question, though the first-named author does not commit himself to the pangen hypothesis. These writers have maintained that the particular mode of development in a given region or blastomere of the egg is a result of its relation to the remainder of the mass, i.e. a product of what may be called the intra-embryonic environment. Both at first assumed not only that the nuclei are equivalent, but also that the cytoplasmic regions of the egg are isotropic, i.e. primarily composed of the same materials and equivalent in structure. Hertwig insisted that the organism develops as a whole as the result of a formative power pervading the entire mass ; that differentiation is but an expression of this power acting at particular points ; and that the development of each part is, therefore, dependent on that of the " According to my conception," said Hertwig, " each of the first two blastomeres contains the formative and differentiating forces not simply for the production of a half-body, but for the entire organism ; the left blastomere develops into the left half of the body only because it is placed in relation to a right blastomere." 2 Again, in a later paper : — " The egg is a specifically

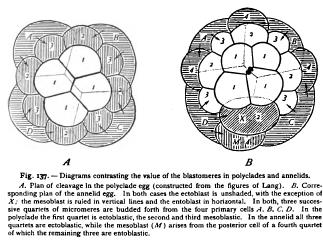

organized elementary organism that develops epigenetically by breaking up into cells and their subsequent differentiation. Since every elementary part (i.e. cell) arises through the division of the germ, or fertilized egg, it contains also the germ of the whole,' but during the process of development it becomes ever more precisely differentiated and determined by the formation of cytoplasmic products according to its position with reference to the entire organism (blastula, gastrula, etc)." 2 Driesch expressed the same view with great clearness and precision shortly after Hertwig : — " The fragments (i.e. cells) produced by cleavage are completely equivalent or indifferent." "The blastomeres of the sea-urchin are to be regarded as forming a uniform material, and they may be thrown about, like balls in a pile, without in the least degree impairing thereby the normal power of development." 3 relative position of a blastomere in the whole determines in general what develops from it; if its position be changed, it gives rise to something different ; in other words, its prospective value is a function of its position." This conclusion undoubtedly expresses a part of the truth, though, as will presently appear, it is too extreme. The relation of the part to the whole must not, however, be conceived as a merely geometrical or mechanical one ; for, in different species of eggs, blastomeres may exactly correspond in origin and relative position, yet have entirely different morphological value. This is strikingly shown by a comparison of the polyclade egg with that of the annelid or gasteropod (Fig. 137). In both cases three quartets of micromeres are successively budded off from the four cells of the four-cell stage in exactly the same manner. The first quartet in both gives rise to ectoderm. Beyond this point, however, the agreement ceases; for the second and third quartets form mesoblast in the polyclade, but ectoblast in the annelid and gasteropod ! In the latter forms the mesoblast lies in a single cell belonging to a fourth quartet of which the other three cells form entoblast. This shows conclusively that the relation of the part to the whole is of an exceedingly subtle character, and that the nature of the individual blastomere depends, not merely upon its geometrical position, but upon its physiological relation to the inherited organization of which it forms a part.