On the Nature and Causes of Differentiation

cytoplasmic and blastomere

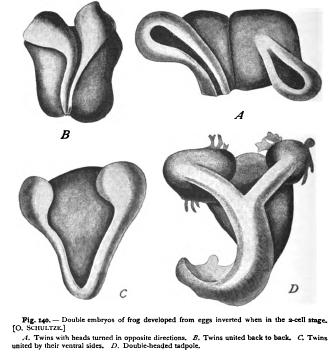

That we are here approaching the true explanation is indicated by certain very remarkable and interesting experiments on the frog's egg which prove that each of the first two blastomeres may give rise either to a half-embryo or to a whole embryo of half size, according to circumstances, and which indicate, furthermore, that these circumstances lie in a measure in the arrangement of the cytoplasmic materials. This most important result, which we owe especially to Morgan,' was reached in the following manner. Born had shown, in 1885, that if frogs' eggs be fastened in an abnormal position, —e.g. upside down, or on the side, — a rearrangement of the egg-material takes place, the heavier deutoplasm sinking towards the lower side, while the nucleus and protoplasm rise. A new axis is thus established in the egg, which has the same relation to the body-axes as in the ordinary development (though the pigment retains its original arrangement). This proves that in eggs of this character (telolecithal) the distribution of deutoplasm, or conversely of protoplasm, is one of the primary formative conditions of the cytoplasm ; and the significant fact is that by artifieially changing this distribution the axis of the embryo is shifted. Oscar Schultze ('94) discovered that if the egg be turned upside down when in the two-cell stage, a whole embryo (or half of a double embryo) might arise from each blastomere instead of a half-embryo as in the normal development, and that the axes of these embryos show no constant relation to one another (Fig. 140). Morgan ('95,3) added the important discovery that either a halfembryo or a whole half-sized dwarf might be formed, according to the position of the blastomere. If, after destruction of one blastomere, the other be allowed to remain in its normal position, a half-embryo always precisely as described by Roux. If, on the other hand, the blastomere be inverted, it may give rise either to a half-embryo 3 or to a whole Morgan therefore concluded that the production of whole embryos by the inverted blastomeres was, in part at least, due to a rearrangement or rotation of the egg-materials under the influence of gravity, the blastomere thus returning, as it were, to a state of equilibrium like that of an entire ovum.

This beautiful experiment gives most conclusive evidence that each of the two blastomeres contains all the materials, nuclear and cytoplasmic, necessary for the formation of a whole body ; and that these materials may be used to build a whole body or half-body, according to the grouping that they assume. After the first cleavage takes place, each blastomere is set, as it were, for a half-development, but not so firmly that a rearrangement is excluded.

I have reached a nearly related result in the case both of Amphioxus and the echinoderms. In Amphioxus the isolated blastomere usually segments like an entire ovum of diminished size. This is, however, not invariable, for a certain proportion of the blastomeres show a more or less marked tendency to divide as if still forming part of an entire embryo. The sea-urchin Toxopneustes reverses this

rule, for the isolated blastomere of the two-cell stage usually shows a perfectly typical half-cleavage, as described by Driesch, but in rare cases it may segment like an entire ovum of half-size (Fig. 132, D) and give rise to an entire blastula.' We may interpret this to mean that in Amphioxus the differentiation of the cytoplasmic substance is at first very slight, or readily alterable, so that the isolated blastomere, as a rule, reverts at once to the condition of the entire ovum. In the sea-urchin, the initial differentiations are more extensive or more firmly established, so that only exceptionally can they be altered. In the snail we have the opposite extreme to Amphioxus, the cytoplasmic conditions having been so firmly established that they cannot be altered, and the development must, from the outset, proceed within the limits thus set up.

Through this conclusion we reconcile, as I believe, the theories of cytoplasmic localization and mosaic development with the hypothesis of cytoplasmic isotropy. Primarily the egg-cytoplasm is isotropic in the sense that its various regions stand in no fixed and necessary relation with the parts to which they respectively give rise. Secondarily, however, it may undergo differentiations through which it acquires a definite regional predetermination which becomes ever more firmly established as development advances. This process does not, however, begin at the same time, or proceed at the same rate in all eggs_ Hence the eggs of different animals may vary widely in this regard at the time cleavage begins, and hence may differ as widely in their power of response to changed conditions.

The origin of the cytoplasmic differentiations existing at the beginning of cleavage has already been considered (p. 285). If the conclusions there reached be placed beside the above, we reach the following conception. The primary determining cause of development lies in the nucleus, which operates by setting up a continuous series of specific metabolic changes in the cytoplasm. This process begins during ovarian growth, establishing the external form of the egg, its primary polarity, and the distribution of substances within it.

The cytoplasmic differentiations thus set up form as it were a framework within which the subsequent operations take place, in a more or less fixed course, and which itself becomes ever more complex as development goes forward. If the cytoplasmic conditions be artificially altered by isolation or other disturbance of the blastomeres, a readjustment may take place and development may be correspondingly altered. Whether such a readjustment is possible, depends on secondary factors — the extent of the primary differentiations, the physical consistency of the egg-substance, the susceptibility of the protoplasm to injury, and doubtless a multitude of others.