Linn I Genus Ulmus

The Etruscan vase form—a base gradually flaring to a round dome—is most common. The trunk soon divides into three or four main limbs with slight but constant divergence as they rise. Their branches follow their example. The divisions are drawn downward by their increasing weight, and the extremi ties are pendulous, sweeping out and down with loads of foliage, luxuriant, but never heavy looking or ungraceful.

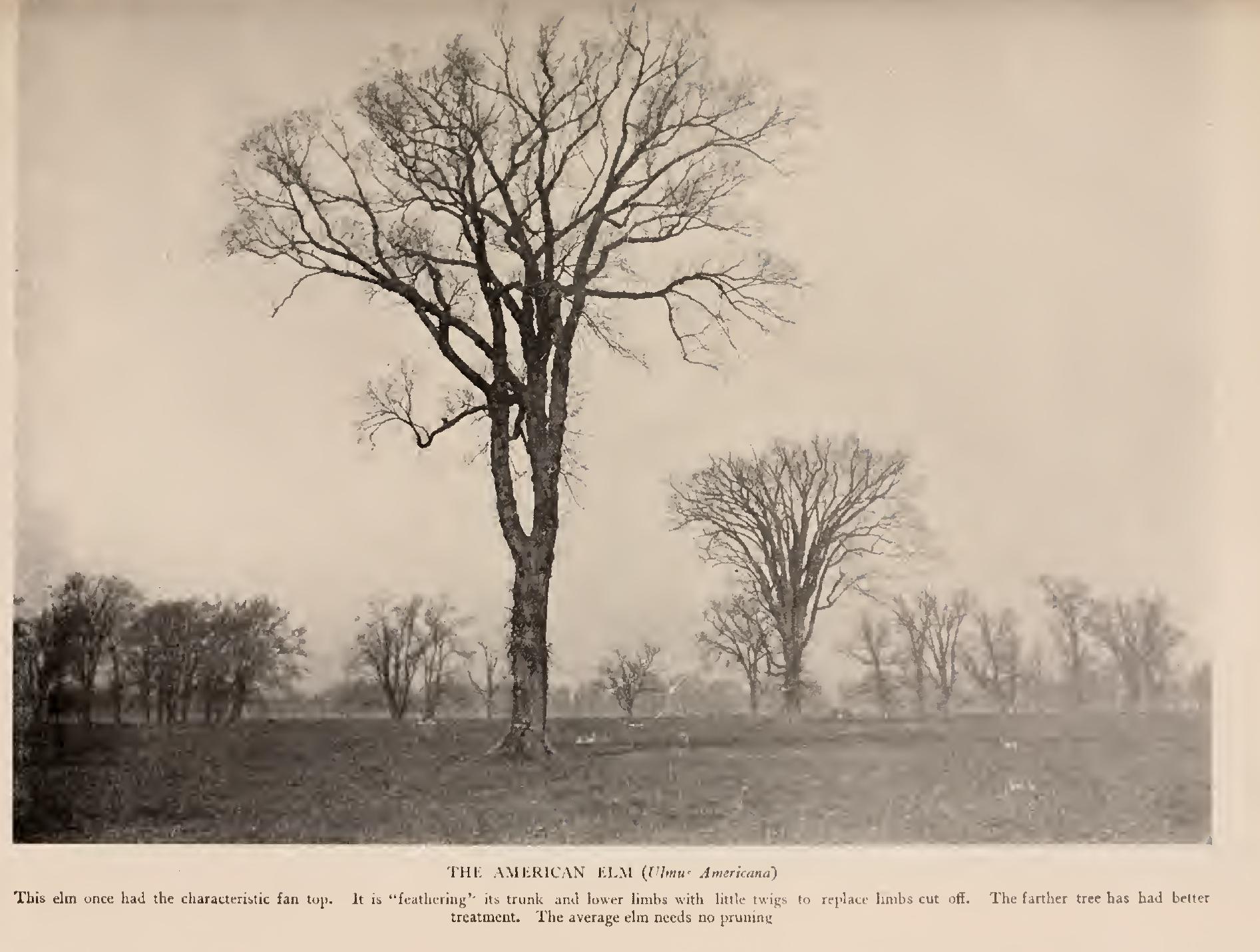

There are narrower elm forms: tall trunks whose limbs form a brush at the top, not unlike a feather duster. Such trees often replace lost outer limbs by a multitude of short leafy twigs, covering the trunks with foliage, thus forming what are known as "feathered elms." The "oak-tree form "—wider and broader than the vase form—reminds one of the ample crown of an oak. But only the outline is suggestive. The limbs are curved, never angular and tortuous like the oak. Grace rather than strength is invariably the expression of the American elm. In good soil the terminal shoots attain great length, and it is not unusual to see an elm of vase shape with the droop of a weeping willow.

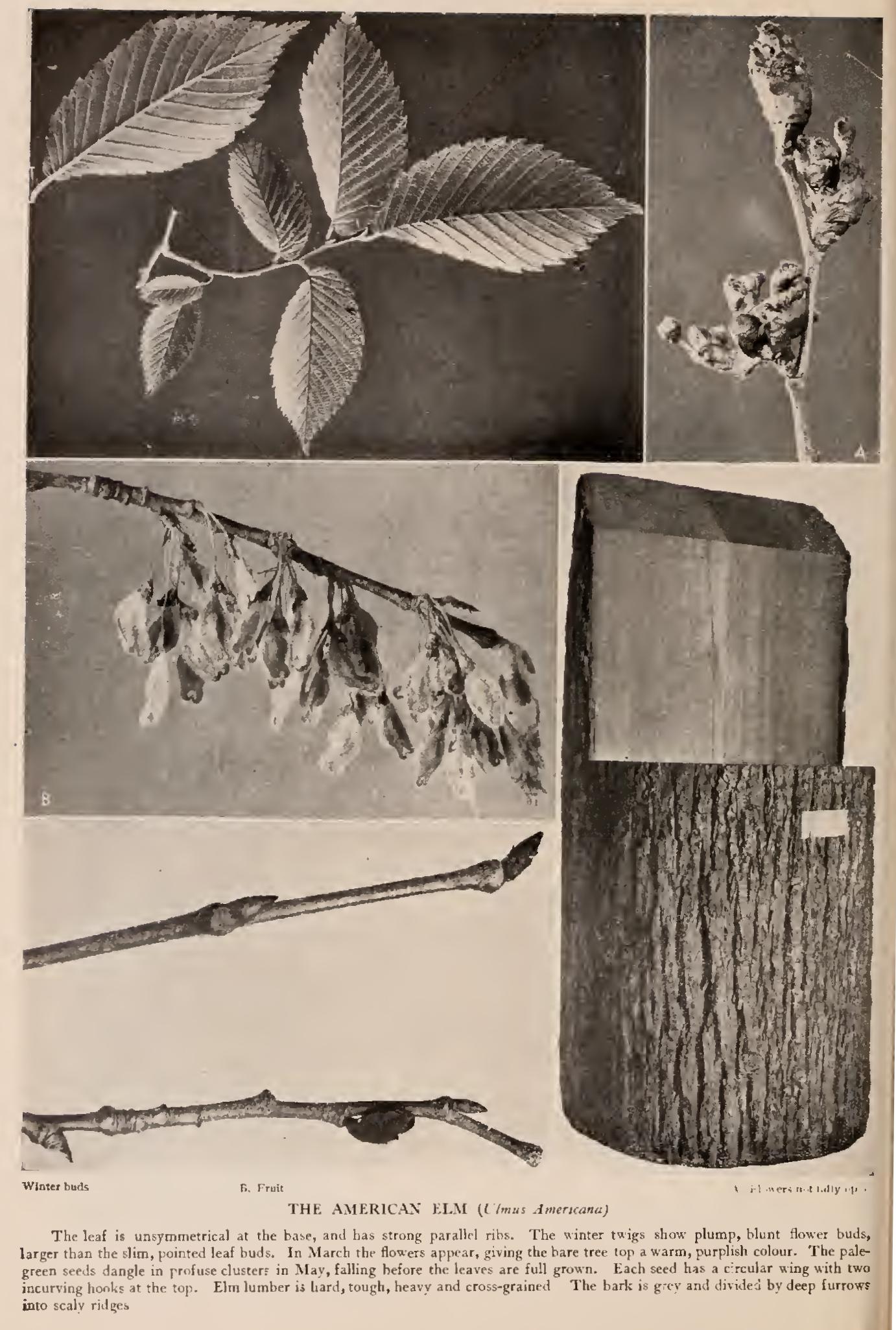

The leaves of the elm are two-ranked, the twigs plume-like. Every chink is filled with a leaf. Break off a branch that faces the sun, and you will be astonished at the twisting and contriving of the leaves, to present an unbroken surface of green. This is known as a "leaf mosaic," and is by no means confined to elms. Any roadside thicket shows the same habit in all its species.

I think, with all due regard for its summer luxuriance, and the grace of its framework in winter, the greatest charm invests the elm of the roadside in the first warm days of spring. The swelling buds are full of promise. A flush of purple overspreads the tree, while snow yet covers the ground. A tremendous "fall of leaves" ensues—for the tiny leaf scales that enclose the elm flowers are but leaves in miniature. The elms are in blossom; they are among the first in the flower procession that silently passes till the witch hazel brings up the rear in October. Then come the little green seeds, winged for flight. These ripen and are scattered before the leaves are open, and the growth of the season's shoots really begins. How much they miss who never see the elms in flower and fruit! The English elm (U. campestris) is a strikingly different tree from its American cousin. Boston Common gives ample opportunity to contrast large specimens of the two species. Dignity • is a characteristic of each. Each bears a luxuriant burden of leaves. The Briton is stocky; the American, airily graceful. One stands heavily "upon its heels," the other on tiptoe. One has a compact crown, the other an open, loose one.

In October the English elm is still bright, dark green; the Amer ican elm has passed into the sere and yellow leaf.

The elm is the favourite tree of the hang bird, or Baltimore oriole, in America. In winter the deserted nests swing from the high outer limbs, where the leaves concealed them in nesting time. The English elm at home is the red-breast's tree. These birds build, not in the upper limbs, but in those that grow down near the trunk, and come earliest into leaf.

Classical literature proves the antiquity and the great im portance of the elms of southern Europe. The Romans used elm leaves as forage for cattle, In the vineyards elms were planted to support the vines. The trees were well pruned so they'should not overshadow the grapes. It was counted danger ous to give bees freedom to visit blooming elms, lest they become surfeited, and sicken as a result. In this opinion the early observers were evidently mistaken. Virgil discourses upon the successful grafting of oak upon elm, and describes swine eating acorns that dropped from the fruiting branches of this wonderful tree. Experiment long ago proved the fallacy of this report. In England the rustic still watches the elm for signal to sow his grain, relying on the old saw: "When the elme leaf is as big as a mouse's ear, Then to sow barley never fear." The witch hazel (Harnamelis Virginiana) does not grow in England, but the wych elm was known in some regions by this name, because its leaf is hazel-like. Long bows were anciently made of its wood, and it was mentioned in the "Statutes of England." Slippery Elm, Red Elm (U. fulva, Michx.)—Fast-growing tree, 6o to 70 feet high, with erect, spreading branches, forming a broad, open head. Twigs stout, rusty, downy. Bark brown ish, rough, scaly. Wood strong, hard, heavy, coarse, reddish brown, durable in soil. Buds densely rusty, pubescent; large, blunt. Leaves alternate, deciduous, 2-ranked, broadly oval, 4 to 7 inches long, irregularly heart shaped at base, acuminate at apex, doubly serrate, strongly ribbed; on short, stout petiole; surface rough both ways, stiff, harsh. Flowers, April, before leaves, fascicled, numerous, Fruits, May, rounded, hairy, only on seed, wing not ciliate, margined. Preferred habitat, fertile soil along streams. Distribution, lower St. Lawrence River, through Ontario to Dakota and Nebraska; south to Florida; west to Texas. Uses: Wood used as fence posts and railroad ties; for wheel hubs, sills and agricultural implements. Mucila ginous inner bark used to allay fever and inflammation.